Assaf Orion is a senior research fellow at Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies and director of the Israel-China research program. He is also an international fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Orion, a retired brigadier general, was responsible for strategic policy formulation, international cooperation, and military diplomacy in the Israeli Defense Forces.

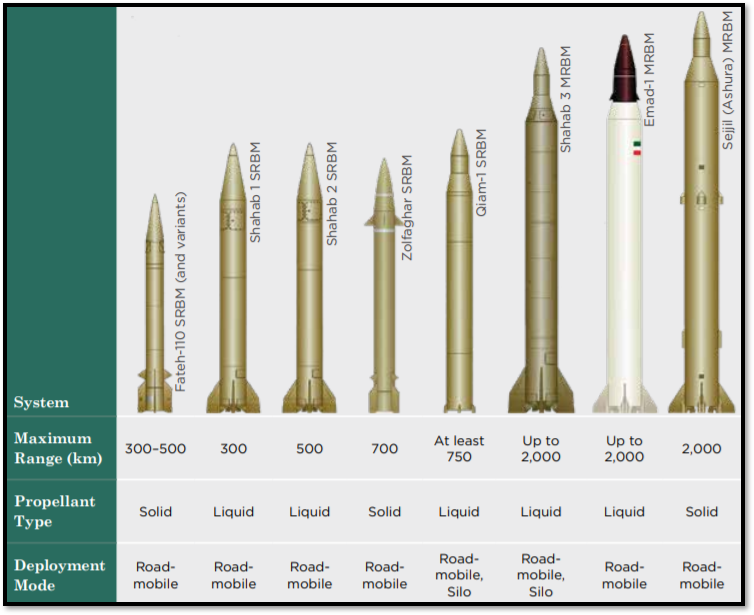

In the 1980s and 1990s, Iran acquired Soviet and North Korean missiles and converted them to make its Shahab-1, Shahab-2 and Shahab-3 missiles. Today, Iran produces its own arsenal of ballistic and cruise missiles. How did Iran build up its own domestic missile industry? How has Iran innovated on earlier missile designs?

The origins of Iran's missile technology were Soviet, North Korean and possibly Chinese. This basic technology was then reverse engineered, enhanced and produced domestically. North Korea may have sold some of these designs to Syria, an important partner in Iran's network, which includes rocket and missile factories in Syria.

On ballistic missiles, the ultimate cover for Iran’s intercontinental missiles—including its participation in the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization (APSCO)—is its space program. On cruise missiles and anti-ship missiles, there are several Iranian derivatives of Chinese missiles, such as the C-802 and the C-704. Israel was on the receiving end of an Iranian C-802 launched by Hezbollah in 2006, and in recent years similar weapons were launched by Yemen's Houthis against U.S. and U.A.E. vessels.

What role do ballistic and cruise missiles play in Iranian military strategy? Are they meant solely to deter attacks on Iran, or do missiles serve offensive purposes too?

Strategically, there is no difference between the ability to use missiles offensively and using that offensive potential for deterrence, compelling behavior change in an enemy or dissuading an enemy from action. Iran's art of war is to avoid war as much as possible; that is partly achieved by repeatedly threatening war. The main formative period for Iranian grand strategy was the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. Lesson one: War is costly in blood and treasure. Lesson two: Don't fight at home and take your war elsewhere—as far as possible from your borders. Lesson three: Don't wage war with your own flesh and blood.

Direct warfighting is very costly, hence Iran's indirect approach to warfare. In its wars by proxy, Iran fights with other people hands from other people’s lands. Ballistic missiles are another aspect of indirect warfare. Rather than punching through the enemy's military, Iran fires over another country’s defense systems, over its protective forces, and strikes directly at the rear—at its populace and its strategic assets. This approach shakes the 'Clausewitzian trinity' of national security—the government, the military and the people—by undermining people’s confidence and their trust in the government and military. During the Iran-Iraq in the 1980s, Iran was the victim of a similar approach when Iraq shot Scud missiles into its cities.

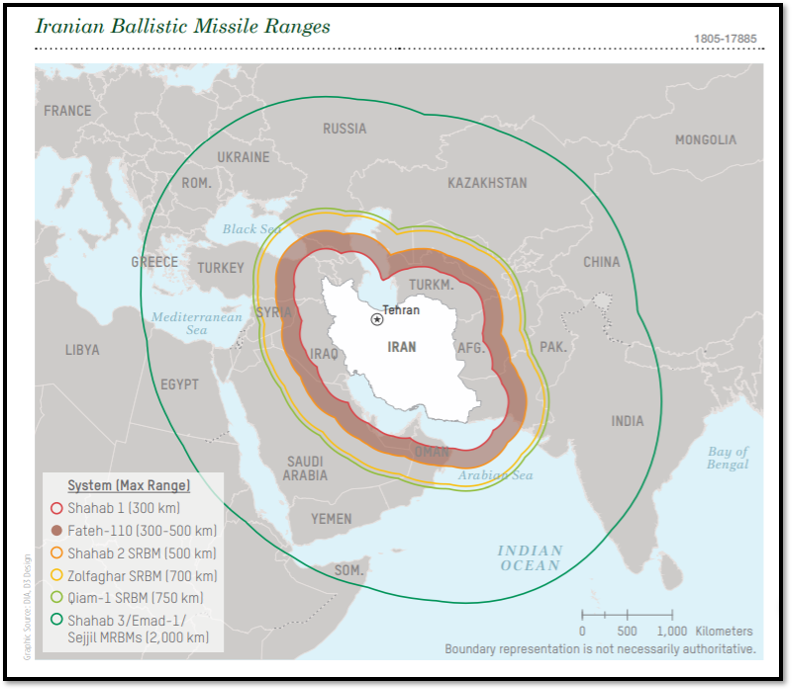

When a country like Iran lacks an air force and needs range, it needs ballistic missiles. If it wants another angle of penetration, it needs cruise missiles. Heavy weight missiles and cruise missiles are superb platforms for delivery of nuclear weapons. It's not very cost-effective for Iran to hurl half a ton of high explosives 1,600 km (994 miles). But if Iran put a nuclear payload on the missile, it would be a totally different game. Missile ranges indicate what countries Iran is trying to engage, threaten or impress. They suggest a country’s implied power to hurt, expressed in the grammar of trajectories.

Related Material:

- Iran's Missiles: Evolution and Arsenal

- Iran's Missiles: Infographics and Photos

- Iran's Missiles: Timeline of Attacks

- Iran's Missiles: Transfer to Proxies

What are the advantages and disadvantages of having missiles – rather than fighter aircraft or drones – as the core of air power? What other countries rely more on missiles than warplanes?

Countries that can’t afford to have an air force superior to its enemies will opt for missiles, the second-best option. An air force has more flexible fire power, but it is dependent on access on airfields, and its planes are vulnerable to air defenses. Missiles are a substitute if airfields are threatened or when air superiority is unattainable. Iran's development of drones and cruise missiles (which it showcased in military exercises in January 2021) needs to be carefully monitored because it could be trying to take the next step forward in air warfare with precision swarms of drones, multiple rockets, missiles and launching platforms, and saturation missile strikes that overwhelm rival defenses.

Iran is not the only country that relies on missiles. Syria had an air force but was always inferior militarily compared to Israel’s air power. So, it sought firepower with ballistic missiles and rockets, and also added chemical weapons for military and psychological impact. Syria exhausted most of its capabilities against its own population. It repeatedly attacked populated areas with poisonous materials even after it pledged to disarm its chemical arsenal. But Syria is expected to try to rebuild its military capabilities, which will depend on what it can afford. Russia and Iran already assist it with that rebuilding.

Other countries, notably China, although it has a significant air force, rely heavily on a wide arsenal of missiles. North Korea also relies heavily on missiles. Rivals of the United States want to compensate or complement their inferior aerial punch with missiles, which are weapons that have better penetration and different vulnerabilities than warplanes.

Iran has increased its arsenal of medium-range ballistic missiles that can strike targets as far away as 2,000 km (1242 miles). Iran has not yet developed longer-range missiles, but the Revolutionary Guards have warned that they might in the future. Where has Iran used its medium-range missiles? Against what targets? And why?

An Iranian missile with a medium range of 2,000 km (or 1,242 miles) could strike Israel to its west and Russia to its north. It could also hit all of Iran's neighbors—any of the Gulf states, Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and the Central Asia republics—and as far as Egypt in North Africa. But Iran has fewer missiles with a longer range due to the cost of launching a missile into space.

Iran’s medium-range missiles are designed to impress, threaten and deter its neighbors and rivals. Iran could threaten Saudi Arabia with missiles that have a range of 1,000 km to 1,500 km (620 miles to 900 miles). Iran could threaten Israel with missiles that have a range of 1,500 km to 2,000 km (900 miles to 1242 miles). Iran would need cruise missiles with even longer ranges to hit Saudi Arabia or Israel from several directions.

Why would Iran want intermediate-range missiles of 3,000 km to 5,500 km (or 1,864 miles to 3,400 miles), or intercontinental ballistic missiles, or anything greater than 5,500 km (or 3,400 miles) in the future? And what might be its primary targets?

Europe would probably be the primary target. European countries might become a target if they joined the United States in militarily challenging the Iranian regime. Most missiles have strategic utility, not just military or physical impact. They could enhance Iran's leverage in negotiations with strategic partners, like Russia, or adversaries, like Western nations and NATO. But Iran’s pursuit of longer range missiles also has a reverse effect. Iran could provoke wider opposition and pushback if it boasts about its missile capabilities.

Iran’s missiles are not just for show. The longer range missiles boost Iran's standing among nations with ballistic missiles. They raise Iran from being just a Middle East power; Tehran becomes a power in Eurasia. If it developed intercontinental missiles, it could become a global power.

At least four times — in 2015, 2019, 2020 and 2021— the Revolutionary Guards unveiled underground “missile cities” buried along the Gulf coast. Why does Iran need to hide its missiles? How difficult is it to find and destroy the missile cities?

Such "missile cities" are mostly relevant to maritime conflict around the Gulf. Iran faces a tension between the ability to strike quickly and the survival of its missile arsenal. It’s a tricky balance. Iran's built its missile cities to signal that it can still inflict immense pain even if an enemy tries to crush it—so back off. The security of these missile cities is unclear. Unlike missiles that are mobile, the missiles stored in underground facilities are more vulnerable to air strikes. The more a country invests in creating infrastructure, the more time an enemy has to prepare to counter it.

How accurate are Iran’s missiles? How have Iran’s precision missiles changed the military balance of power in the Middle East?

The difference between a precise missile and imprecise missile is in the probability of impact. An imprecise weapon system may require more missiles to hit a small target. A precise weapon system usually requires fewer missiles to a target. One hit for every 20 launches is a poor ratio. One hit in every five or 10 launches is better precision or a better ratio. The missiles in many Western militaries can get within a meter of a target with 90 percent accuracy.

Precision technology is important because it converts missiles that mainly have psychological impact into cost-effective and more accurate weapons. Precise missiles can take out power stations, military headquarters, ships and airfields, with rippling impact nationwide. Precision missiles allow Iran to pick the exact time and location of a strike. They allow Iran and their proxies to conduct decapitation strikes against enemy targets, as the Houthi rebels did in striking Yemen's cabinet at the Aden airport in December 2020.

Small countries like Israel have few high-value targets that are considered “essential nodes.” If Iran has more precise missiles, Israel has a larger problem. Israel’s missile defense interception system ignores projectiles that are likely to miss their targets. If Iran’s missiles become more precise, Israel needs to invest in more missile defense.

In February 2019, Iran tested a new generation of long-range cruise missiles, which can fly at lower altitudes and are harder for radar to detect. What advantages do cruise missiles have over ballistic missiles?

But Iran is a late arrival to cruise missiles, which involve an older technology. The United States has had Tomahawk cruise missiles since 1983. Iran's cruise missiles probably don’t cost one million dollars apiece. But they are good enough because they are more affordable and still effective.

What did U.S., Israeli and Gulf military planners learn from Iran’s two missile attacks: The first was on the Abqaiq and Khurais oil facilities in Saudi Arabia in September 2019? The second was the ballistic missile attack on the Ayn al Asad airbase in Iraq—which was used by U.S. troops—in January 2020? How have the United States, Israel and the Gulf states adjusted their military strategy in response?

Today, Iran’s missiles are more precise at shorter ranges—as was evident in the attack on Saudi Arabia—and at longer ranges too. Iran launched ballistic missiles at jihadi targets in eastern Syria in June 2017. It fired missiles into Iraqi Kurdistan in September 2018. And it struck Ayn al Asad military base in January 2020. Iran can target specific structures, not just broad areas, sometimes with real-time reconnaissance by drones over the target. Iran’s capabilities are improving.

Today, Iran’s missiles are more precise at shorter ranges—as was evident in the attack on Saudi Arabia—and at longer ranges too. Iran launched ballistic missiles at jihadi targets in eastern Syria in June 2017. It fired missiles into Iraqi Kurdistan in September 2018. And it struck Ayn al Asad military base in January 2020. Iran can target specific structures, not just broad areas, sometimes with real-time reconnaissance by drones over the target. Iran’s capabilities are improving.

The United States, Israel and some Gulf countries have expanded their air defense systems. When the Houthis threatened to attack Israel in 2019, Israel added missile detection and defense systems facing south. The Israeli press reported that Israel deployed Patriot missile defense batteries in Eilat on the Red Sea. The United States also flew B-52 bombers over the Persian Gulf as a warning against attacking American targets.

The United States, Israel and the Gulf all need better early-warning, detection, interception and protection systems to defend against potential attacks by Iran or its proxies. They also need counter-strike capabilities. Iran's aggression after Qassem Soleimani’s assassination decreased. It retaliated on Ayn al Asad and continued harassing the Green Zone in Iraq, but those attacks were more indirect and were less intense than previous attacks on Americans in Iraq.

In 2019 and 2020, the United States deployed Patriot and THAAD missile defense systems in Israel, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Can these defense systems intercept all Iranian cruise and ballistic missiles? How else do U.S. partners in the region defend against Iran's missiles?

The general approach in Israel has been to build a multi-tiered missile defense system that operates at different ranges and altitudes.

- Iron Dome [which fires projectiles that can intercept low-altitude and short-range missiles and rockets at ranges of 4 km to 70 km or 2.5 miles to 43 miles]

- David's Sling [which fires projectiles that can intercept medium- to long-range rockets, cruise missiles and ballistic missiles at ranges of 40 km to 300 km or 25 miles to 186 miles]

- Patriot batteries [which fires projectiles that can intercept ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and aircraft at ranges of 160 km or 100 miles]

- And Arrow-3 [which fires projectiles that can hit medium-range ballistic missiles outside the atmosphere at ranges of 2,400 km or 1491 miles]

Missile defenses are part of a systemic response that also involves intelligence, detection, integration, early warning, communication, and civil defense. Israel probably has an 80 percent to 90 percent success rate of interception. But if a country is not ready or an attack is unexpected—as happened in the attack on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq oil facility—it has to decide where to point its defenses.

Iran has supplied its partners and proxy groups with a diverse inventory of rockets, cruise missiles and ballistic missiles. What is Iran’s goal? Which groups have received the most advanced missiles? Why?

The Iranian art of indirect warfare will fight to the last Lebanese, the last Syrian, the last Afghani or the last Pakistani militiaman. The myriad militias in Syria have recruits from all of these nations. In Lebanon, Hezbollah is the flagship of Iranian proxy warfare.

The Iranian art of indirect warfare will fight to the last Lebanese, the last Syrian, the last Afghani or the last Pakistani militiaman. The myriad militias in Syria have recruits from all of these nations. In Lebanon, Hezbollah is the flagship of Iranian proxy warfare.

For Iran, hurling half a ton of explosives into Israel from 1,600 km (1,000 miles) away is expensive. It's more cost-efficient to have proxies use missiles from closer range. In Lebanon, for example, Hezbollah can fire more rockets or short-range missiles and saturate its targets in Israel—and not have to spill its own blood. Hezbollah will do the job and Lebanon will pay the price. Iran is waging a slow motion, low-burning war in which it is the mastermind, while the proxies are cannon fodder.

Saudi Arabia has the same problem. It has spent billions of dollars fighting the Houthi rebels in Yemen. Iran’s costs to support the Houthis are probably in the tens of millions of dollars.

In December 2020, Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah claimed that Hezbollah had doubled its inventory of precision-guided missiles in the previous year. Iran also shipped kits to Lebanon to convert unguided rockets into precision missiles. What is required to convert the Zelzal-2, an unguided short-range rocket with a range of 210 km (130 miles), into a precision-guided missile with a range of approximately 300 km (186 miles)? How many rockets have been converted? Has Hezbollah’s larger missile stock changed the balance of power with Israel? And what has Israel done to counter Hezbollah’s arsenal?

Hezbollah has tens of thousands of short-range rockets—10 km to 40 km (or 6 miles to 25 miles). It has thousands of medium-range rockets—50 km to 100 km (or 31 miles to 62 miles). It has hundreds of rockets that can be fired several hundred kilometers. It probably has dozens of missiles or rockets that go further than that. There are very good materials by the IDF showing how Hezbollah has modified its longer-range rockets. The kits add a section to the rocket; they include a navigational unit and rotating fins that corrects a weapon’s course and allows it to maneuver.

A precise missile is more accurate and more maneuverable, which adds an additional challenge for missile defense systems. Estimates published in the Israeli press claim that Hezbollah has several dozen precision-guided missiles. Its arsenal does not compare to Israel’s arsenal in either quantity or quality. Israel has tens of thousands of first-rate precision bombs, so it potentially could hit tens of thousands of targets.

An IDF video on Iran's efforts to supply precision-guided missiles to Hezbollah

Israel can impose a terrible cost on Hezbollah yet that will not compensate for the damage it could inflict on Israel. Hezbollah could use precise missiles to try to disrupt Israeli missile defenses. It could try to attack Israel’s infrastructure. It could also try to disrupt Israeli military preparation because the IDF is heavily reliant on reservists who need be mobilized. Life in Israel could be disrupted if Hezbollah were to start bombing those nodes before Israel was fully mobilized.

Hezbollah could also seek to terrorize Israel's civilian population. In the 1980s, a quarter of Tehran’s population fled from Iraqi Scuds and the threat of Iraq using chemical weapons. From its own experience, Iran knows how to strategize its “war of cities.”

Israel has a multifaceted strategy to respond. Its civil defense system is better than civil defense in either Lebanon or Iran. Its early warning is better. Its missile defense is world-class. But the Israeli military prefers to destroy missiles before they are launched with preemptive strikes. The IDF also wages a so-called “campaign between the wars” to preempt, disrupt and degrade its adversary’s military capabilities. But with Iran, it’s a long twilight struggle, in which both parties seek to avoid war. Yet this dynamic is not risk free and may at some point escalate beyond the parties' careful calculations.