Kelsey Davenport is the Director for Nonproliferation Policy at the Arms Control Association.

Where does Iran’s nuclear program stand at the beginning of 2025?

Iran has become a nuclear weapons threshold state. It has developed the technologies and capabilities that would allow Tehran to move quickly to develop nuclear weapons, if the political decision were made to do so. In the last several months of 2024, Iran took steps that dramatically expanded its capacity to enrich uranium and its production of uranium that’s enriched to near weapons-grade levels. Specifically, Iran announced decisions to increase production of uranium enriched to 60 percent and to begin enriching uranium using additional advanced centrifuges, which work more efficiently.

Uranium typically is enriched to 90 percent to fuel a weapon, but enriching from 60 percent to 90 percent is relatively easy. Iran's existing stockpile of highly enriched uranium, combined with its capacity to enrich more at a rapid pace, would allow it to produce enough weapons-grade uranium for about five to six weapons in less than two weeks.

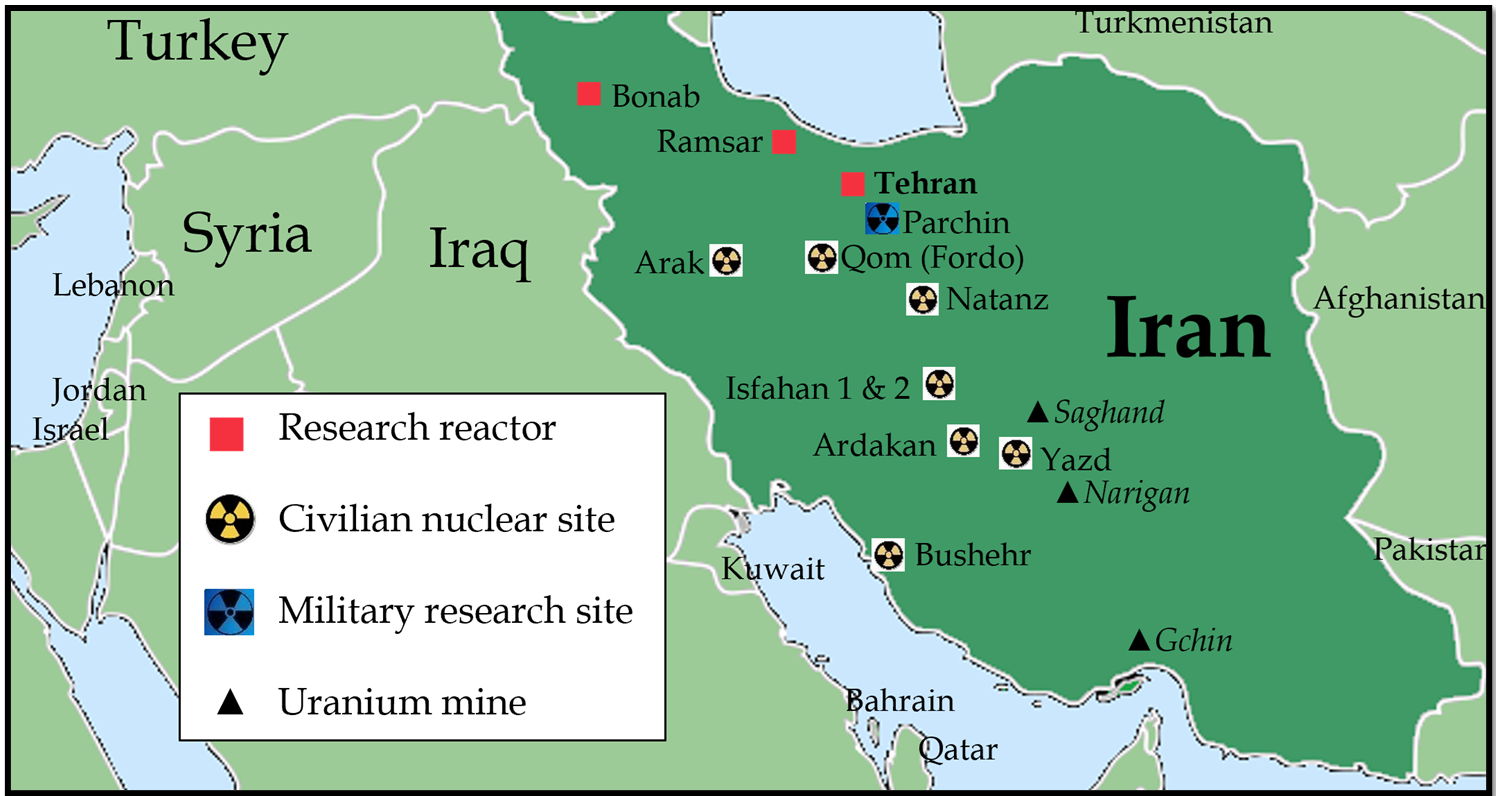

The expansion of 60 percent uranium production was also worrisome because it was taking place at the Fordo facility, which is deeply buried inside a mountain. Fordo would be a challenge for Israel or the United States to destroy if either decided to try to disrupt Iran's nuclear program with a military strike.

With Iran facing setbacks on various fronts, what openings do you see for de-escalation of the Iranian nuclear threat in 2025? What steps might Tehran be willing to take—and in exchange for what?

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian has made clear that Tehran is interested in a nuclear agreement and is willing to negotiate with the Trump administration. Iranian officials also have suggested in meetings with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) that they are looking for relief from U.S. sanctions in return for further cooperation with the U.N. watchdog.

When Rafael Grossi, the IAEA director general, traveled to Tehran in November of 2024, he raised the prospect of Iran capping its stockpile of 60 percent enriched uranium and stated publicly that Tehran was willing to entertain that proposal. This suggests that Tehran could consider more transparency measures or restrictions on certain activities.

But a new nuclear deal would most likely need to be small in scope because the window for diplomacy is very narrow. When the Trump administration takes office in January 2025, it will only have six to eight months to negotiate a deal and then implement it before October 2025, which is widely viewed as a deadline for progress. So, any de-escalation package would need to be narrowly construed, fairly straightforward and quickly implementable by both the United States and Iran. Ideally, a narrow agreement would buy time and create political will for Washington and Tehran to negotiate a more comprehensive nuclear accord.

Why is October 2025 so critical? Is that because the so-called “snapback” mechanism – which could quickly reimpose U.N. sanctions on Iran for violating its nuclear commitments – is due to expire then?

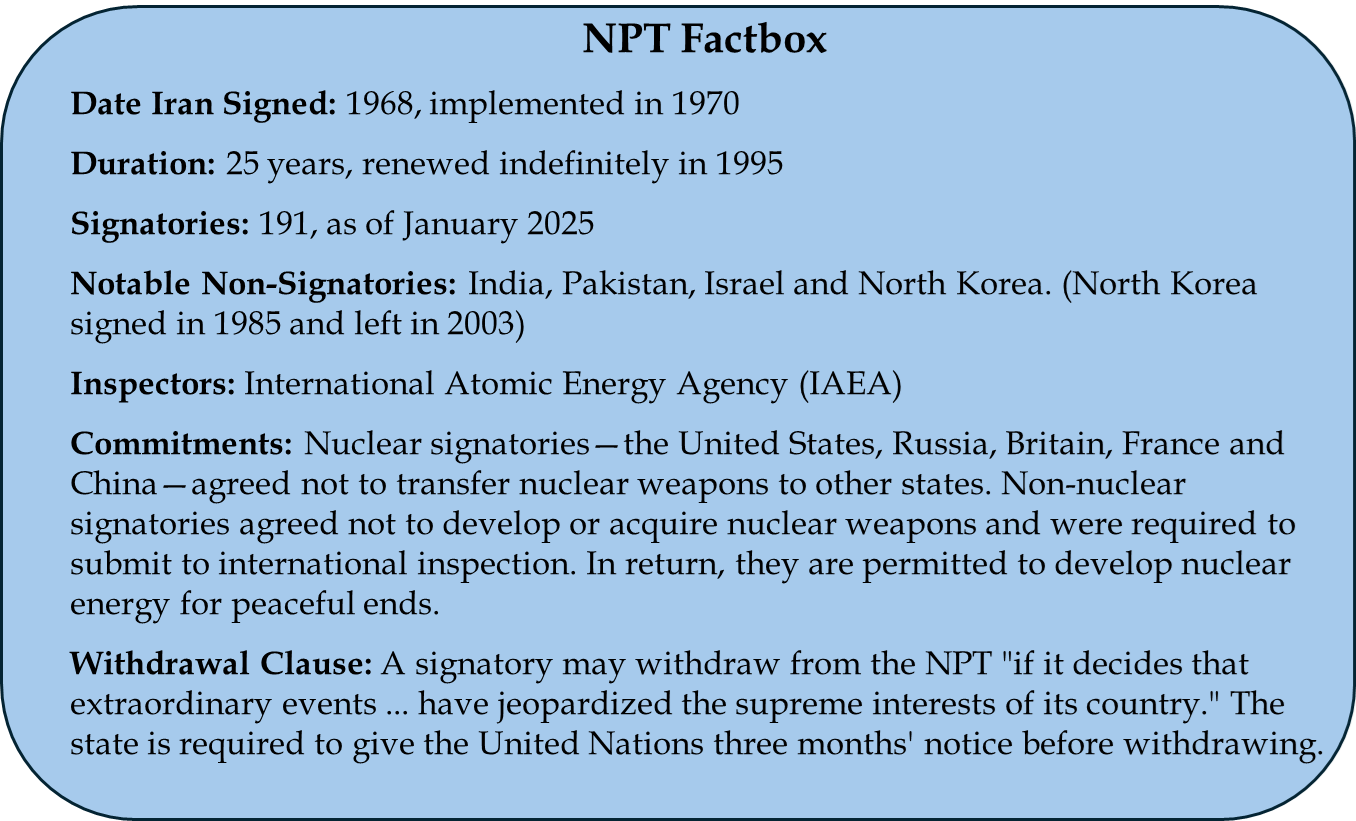

The 2015 nuclear deal, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was endorsed by U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231, which modified the Security Council sanctions on Iran and lifted those measures over time. A mechanism within Resolution 2231 allows for one of the parties of the nuclear deal to reimpose those U.N. sanctions on Iran using a process that cannot be vetoed by any member of the Security Council. That mechanism, known as snapback, expires in October 2025.

The United States can no longer use the snapback mechanism because President Trump withdrew from the nuclear deal in May 2018. So, one of the European powers would probably need to start the process. In December 2024, Britain, France and Germany warned that they were ready to trigger the mechanism.

“Iran must deescalate its nuclear program to create the political environment conducive to meaningful progress and a negotiated solution,” their U.N. ambassadors wrote in a letter to the Security Council. “We reiterate our determination to use all diplomatic tools to prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon, including using snapback if necessary.”

The likelihood of triggering snapback will continue to increase – absent a change in Iran’s activities – because the Security Council would face an effective obstacle to imposing punitive measures on Iran after October 2025. That’s because Russia, which has been strengthening relations with Iran, would almost certainly veto any new Security Council resolution targeting Iran’s nuclear program, even if it were warranted. For years, Russia has been shielding Iran from consequences for violating its nuclear safeguards commitments.

Triggering snapback would demonstrate to Iran that there are consequences for its failure to meet its nuclear obligations. The reimposition of economic sanctions could also build pressure on Iran to negotiate a new nuclear deal.

But there are potential pitfalls to utilizing the snapback provision before it expires. Iran has warned that it would respond by withdrawing from the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which forbids it from building a nuclear weapon and requires IAEA monitoring. Withdrawing from the NPT does not necessarily mean Tehran would pursue nuclear weapons, but the move would start a new clock during the withdrawal period, when diplomacy would likely focus on keeping Iran in the Treaty. Withdrawing would give Iran more leverage because it could trade a return to the NPT in exchange for concessions. But it is risky for Iran as well. Withdrawal could trigger military strikes against its nuclear facilities.

What is the danger that Iran would withdraw from the Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and openly sprint toward a weapon?

If Iran decides to develop nuclear weapons, it has two options. The first is to withdraw from the NPT and revoke its safeguards agreement, which would remove international inspectors. That would allow it to break out – produce enough 90 percent enriched uranium for one weapon – using its declared nuclear facilities. This would be a risky move that would send a clear signal of intent to weaponize and create a window for the United States and Israel to disrupt that process. The United States and Israel could target those declared sites before Iran could enrich enough material and divert it to covert sites for weaponization. Alternatively, Iran could try to develop nuclear weapons in secret before or without withdrawing from the NPT.

Rather than openly building a nuclear weapon, could Iran produce a weapon clandestinely? If so, how?

Iran could attempt to break out using covert, undeclared sites by developing illicit facilities for converting uranium ore to gas form for enrichment or by siphoning off uranium from its declared enrichment sites. In either scenario, it would need to enrich that material to weapons-grade levels and then take several other steps to produce a weapon. Western intelligence agencies have a strong track record of detecting clandestine Iranian nuclear facilities. Iran's nuclear advances, however, would enable it to build an undeclared facility with a smaller footprint than in the past. Such a facility could be more challenging for foreign intelligence to detect.

Furthermore, the IAEA has not had access to Iran’s centrifuge production facilities since February 2021. Director General Grossi acknowledged that Iran could have produced centrifuges and diverted them to a covert location without IAEA knowledge. So, the lack of monitoring coupled with Iran's nuclear advances increases the risk that Tehran could build a covert facility and evade detection, at least long enough to produce enough weapons-grade material. If Iran diverted more efficient centrifuges to a covert site, and it used uranium that was already enriched to the 60 percent level, it could move very quickly to enrich that material to weapons grade. So, a secret facility would not need to remain secret for as long as it would have when Iran’s centrifuges were less efficient.

Former and current officials have increasingly called for Iran to produce nuclear weapons as a potential option to enhance deterrence. Why? What may factor into Tehran’s calculus?

Iran's nuclear policy doctrine began to shift in 2024. Officials increasingly raised the prospect publicly that Iran may need nuclear weapons for its security, which contradicts the fatwa (religious edict) issued by the Supreme Leader in 2003 that forbids nuclear weapons. An official suggested that Iran could rethink its nuclear doctrine if national security requirements changed. So far, Tehran has attempted to use its threshold status as a deterrent by threatening to cross the nuclear weapons threshold if its territorial integrity is challenged or its nuclear program is attacked. But that calculus could shift if Iranian leaders decide they need a stronger deterrent because conventional military options no longer appear adequate for its security and to deter attacks against its territory.

In 2024, the military capabilities of Iran's partners and proxies in the region were significantly degraded. The fall of the Assad regime in Syria raised questions as to whether Iran will be able to resupply Hezbollah and rebuild its network of allies that it has historically relied on for deterrence.

Iran has also developed a ballistic missile program as an important conventional deterrent. But its two unprecedented strikes against Israel in 2024 did little damage. The attacks demonstrated the limitations of Iranian missile systems as well as the strength of Israeli missile defenses – and defenses that Israeli partners, such as the United States, can employ to mitigate Iranian strikes. Given what Iran has learned about its missiles and the degradation of Hamas and Hezbollah on the borders of Israel, it may perceive nuclear weapons as necessary to deter future attacks. Any strike on its nuclear sites or other strategic targets, such as oil facilities, could influence that cost-benefit analysis and persuade Iranian leaders that the benefits of nuclear weapons exceed the costs.

Why have the risks of an attack on Iranian nuclear sites increased?

Successive U.S. presidents have stated that the United States will use military force to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons. Iran’s nuclear weapons threshold status and its threats to weaponize increased the likelihood that the United States or Israel will determine that military strikes are necessary.

In late 2024, some Israeli officials argued that the conditions were optimal for striking Iran’s nuclear program. Iran’s air defenses, including advanced Russian S-300 batteries, were damaged in Israel’s counter strike in October, leaving nuclear sites more exposed. “There is an opportunity to achieve the most important goal - to thwart and remove the threat of destruction hanging over the State of Israel,” Defense Minister Israel Katz said in November. He cited a “broad national and defense establishment consensus” and “an understanding that this is doable - not only on the security front, but also on the diplomatic front.”

Furthermore, Israeli strikes on Iranian partners and proxies, particularly Hezbollah, degraded their capability to retaliate for any strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities.

If Iran made the political decision to weaponize, how long would it take to manufacture usable nuclear weapons?

If Iran decided to weaponize, it could produce enough weapons-grade uranium for several nuclear weapons in less than two weeks. But that's just the beginning of the weaponization process. Iran would need to convert that material from gas into a metallic form. It would then need to shape the material and pair it with an explosives package. Producing a crude bomb itself could probably be done within six months. But if Iran wanted to marry a more sophisticated weapon capable of being delivered by a missile, producing nuclear warheads that fit on the tip of a ballistic missile could take between one and two years.

But either way, as far as the rest of the world is concerned, the window for disrupting the weaponization process may close once the weapons-grade uranium is produced and diverted to covert sites.

If diplomacy fails, what options remain to stop Iran from producing a nuclear weapon?

There is no realistic military option to block Iran from ultimately developing nuclear weapons. Iran has the requisite capability and the knowledge. Due to Tehran’s advances, kinetic options, including military strikes and sabotage, can only set the program back so far. Destroying all of Iran’s declared sites, especially Fordo, would be challenging. And even if that were possible, airstrikes could prove futile if key equipment and raw materials were already diverted to covert sites. Iran's experience building more efficient centrifuges and enriching uranium to higher levels could allow it to rebuild more quickly with the intention to develop nuclear weapons, which it would have every incentive to do if the West mounted an attack aiming at its nuclear capability.