Original chapter by Michael Adler

- Iran is a charter member of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the guide for the global fight against the spread of atomic weapons. Iran insists its nuclear program is for energy, not a bomb.

- Iran cites the NPT to justify its nuclear work, including uranium enrichment, which can be used to generate electricity or to make a bomb. Article IV guarantees “the inalienable right of all the Parties to the Treaty to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes without discrimination.”

- Iran claims to honor the NPT obligations for monitoring its atomic program. It has been careful not to break the safeguards agreement that allows U.N. inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to verify compliance with the NPT.

- The IAEA cited Iran for breach of safeguards, saying the Islamic Republic hid parts of its nuclear program and failed to answer questions on possible military work. This led the U.N. Security Council to impose sanctions in 2010 to get Iran to provide data and to suspend enrichment to allay fears it seeks nuclear weapons.

- The IAEA will play a critical role in monitoring the implementation of the final nuclear deal reached by Iran and the world’s six major powers on July 14, 2015.

Overview

Iran has been the subject of one of the most intensive investigations in the history of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). It was not always this way. Iran was an original signatory of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation (NPT) Treaty in 1968. The shah concluded an IAEA safeguards agreement in 1974.

After the 1979 revolution, revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini initially opposed a nuclear program as a Western-oriented relic of the monarchy. But Iran and Iraq both did secret nuclear work during their 1980 to 1988 war. In August 2002, an Iranian resistance group revealed that Tehran was hiding two key nuclear plants – one in Natanz to enrich uranium, the other in Arak to produce plutonium. These fissile materials can be fuel for civilian power reactors, but also the raw material for atom bombs. The disclosure set off the current Iranian nuclear dispute.

Iran became a special focus for the IAEA. The U.N. agency, which is based in Vienna, issued 30 reports between June 2003 and September 2010 on Iran’s nuclear program and its covert activities dating back to the 1980s. Tehran initially provided cooperation over and above regular safeguards, allowing inspections of non-nuclear sites, for instance. But on September 24, 2005, the IAEA’s executive board found Iran in non-compliance with the NPT due to “failures and breaches of its obligations to comply with its NPT Safeguards Agreement,” namely for hiding a wide range of strategic nuclear work. The board gave Iran time to answer crucial IAEA questions and to make key scientists available for interviews. It also called on the Islamic Republic to suspend uranium enrichment.

But with Iran moving to enrich, the board decided on February 4, 2006 to take the matter to the U.N. Security Council for possible punitive action. The Security Council imposed four rounds of sanctions to pressure Iran to suspend uranium enrichment, allow tougher inspections and cooperate fully with the IAEA. But by September 2010, Iran continued to enrich uranium and defy the Security Council on grounds that it has the right to the full range of civilian nuclear work under the NPT.

After President Hassan Rouhani came to office in 2013, Iran entered nuclear negotiations with the world's six major powers - Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia, and the United States. In 2015, negotiators reached a final nuclear deal that restricted Iran’s nuclear activities in exchange for sanctions relief. The agreement included provisions to broaden the IAEA’s monitoring activities in Iran. The agency was responsible for verifying Iran’s compliance with the deal. Iran and the IAEA also signed a separate Roadmap to clarify outstanding issues on Iran’s nuclear activities, specifically the possible military dimensions of its nuclear program.

The IAEA role

The IAEA was founded in 1957 as the U.N. branch of the “Atoms for Peace” program proposed by President Dwight Eisenhower. The idea was to make civilian atomic power accessible, in return for nations forswearing the pursuit of nuclear weapons. When the NPT went into effect in 1970, the IAEA became its verification arm. Headquartered in Vienna, Austria, the U.N. watchdog agency investigates national nuclear programs worldwide in order to guarantee that nuclear material is not being diverted for military use.

The IAEA is an essential player in the Iranian nuclear issue, as it is the international community’s eyes and ears monitoring the machines and scientists of the Iranian program. Its role has increased with the growing concern about Iran’s atomic ambitions. Treating Iran as a special case, the IAEA has upped its inspections in the country, carrying out frequent visits to dozens of sites. It has an almost constant presence at key sites, such as the enrichment plant at Natanz. It uses remote cameras, as well as regular and unannounced inspections to verify that nuclear material being used and produced is not diverted for military purposes. Despite this, key questions about Iran’s program remain, namely whether there was weapons work.

Prior to the brokering of the final nuclear deal in 2015, the IAEA had several tasks—and issues—with Iran:

- The IAEA was empowered to monitor all sites where there was nuclear material. But it clashed with Iran over access to sites where nuclear material had not yet been introduced, such as at a reactor being built in Arak that could eventually make plutonium.

- The IAEA was particularly frustrated about Iran blocking access to key Iranian scientists, including Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, who has allegedly led Iran’s atomic weapons work.

- The IAEA monitored Tehran’s compliance with U.N. Security Council resolutions.

- It also oversaw attempts to supply fuel to a research reactor in Tehran.

The IAEA investigation

In response to revelations about Iran’s secret sites, former IAEA chief Mohamed ElBaradei led an inspection of the Natanz enrichment site in February 2003. He issued his first special report on Iran in June 2003. The report gave a glimpse into 18 years of covert Iranian nuclear work. It found that Iran had “failed to meet its obligations under its [NPT] Safeguards Agreement with respect to the reporting of nuclear material, the subsequent processing and use of that material and the declaration of facilities where the material was stored and processed.” These included “failure to declare the import of natural uranium in 1991.”

More followed. The next report in August 2003 revealed that IAEA inspectors had found traces of enriched uranium on centrifuge machines in Natanz. Iran had told the agency, however, that it had not yet introduced nuclear material at this site, which was still under construction. The finding of the uranium particles raised suspicion that Iran was hiding yet more nuclear work. The IAEA called on Iran to make a complete disclosure of its nuclear activities by the end of October 2003.

As the IAEA investigation geared up and the revelations came out, the United States lobbied in Vienna to get the IAEA to declare the Islamic Republic in non-compliance with its safeguards obligations, thus clearing the way to U.N. sanctions. But leading western European states, as well as Russia, feared this could lead to an escalation of moves against Iran, and even war, as had happened in Iraq. The so-called EU-3—Britain, France and Germany—set out to parry U.S. pressure. They maneuvered for talks with Iran, and for keeping the Iran case away from the Security Council in New York.

In a diplomatic coup de theatre, the foreign ministers of Britain, France and Germany made a dramatic, surprise visit to Tehran on October 21, 2003 to strike a deal on resolving the nuclear crisis. Iran agreed to suspend enrichment and to make the requested full declaration to the IAEA about its activities. This kept talks alive and avoided sanctions.

The deal also kept an IAEA report the following November from having the impact the United States had been seeking, namely to be the catalyst for moving towards sanctions. The process begun by the EU-3 meant that Iran would be given more time to answer the IAEA’s questions rather than be referred to New York for punitive measures. In addition, ElBaradei said in his report, in a conclusion the United States blasted as exonerating Iran, that there was no “evidence” Iran was seeking nuclear weapons. Yet, the report was strong. It said, “Iran has failed in a number of instances over an extended period of time to meet its obligations under its Safeguards Agreement with respect to the reporting of nuclear material and its processing and use, as well as the declaration of facilities where such material has been processed and stored.”

IAEA chronology

The evolution of the Iran nuclear crisis can be traced in the actions and reporting of the IAEA. Here is a brief chronology of events leading to Iran being taken to the U.N. Security Council:

- February 24, 2004: The IAEA reports that Iran is working to develop a more powerful centrifuge and on separating Polonium-210, which can be used in weapons.

- March 13, 2004: The IAEA board reprimands Iran for hiding possible weapons-related activities.

- March 17, 2004: Testifying before the U.S. Congress, IAEA chief Mohamed ElBaradei says the “jury is still out” on Iran’s nuclear program.

- November 2004: In the Paris Agreement, European negotiators, the IAEA and Iran agree on the terms to suspend uranium enrichment.

- August 8, 2005: The IAEA reports that Iran had ended suspension and begun work to convert uranium into fuel for enrichment.

- September 2, 2005: The IAEA reports that there are still unresolved issues regarding Iran’s nuclear program and says that full Iranian cooperation is “overdue.”

- September 24, 2005: The IAEA board votes 22-1, with 12 abstentions, to find Iran in “non-compliance” with the NPT’s Safeguards Agreement. This clears the way to report Iran to the Security Council for action.

- February 4, 2006: After failing to win Iran’s cooperation, the IAEA board votes 27-3, with five abstentions, to refer Iran to the Security Council, pending one more report from ElBaradei.

- February 27, 2006: ElBaradei reports that the IAEA is still uncertain about both the scope and nature of Iran’s nuclear program. The report is sent to the Security Council.

Case to the U.N.

After Iran was taken to the Security Council, and especially after the first sanctions were imposed in December 2006, the Iran dossier was divided between New York and Vienna. The IAEA continued monitoring Iran’s activities, but the Security Council decided whether and how to punish the Islamic Republic. Iran reacted by reducing its cooperation with the IAEA. It followed strict safeguards measures, which verify the use of nuclear material. But it no longer allowed inspections at sites that may not have had nuclear material but that were crucial to the atomic program.

Iran and the IAEA were increasingly engaged in a cat-and-mouse game: Iran would build up credibility with concessions and cooperation, only to lose it after revelations of secret activities or failure to provide information about its activities. This pattern continued through September 2009, when the United States and its allies reported that Tehran had been hiding work on a second enrichment site, buried in a mountain near the holy city of Qom.

Iran consistently countered that it cooperated fully with the IAEA. Tehran said it resumed enrichment because the international community backtracked on its promises to help Tehran develop a civilian nuclear energy program and to remove Iran as a “special case” at the IAEA.

Four rounds of punitive U.N. sanctions did little to change Iran’s position or its cooperation with the IAEA. In its September 2010 report, the IAEA said Iran had actively hampered its work by barring two inspectors from the country and even breaking seals on atomic material at Natanz. “Iran has not provided the necessary cooperation to permit the Agency to confirm that all nuclear material in Iran is in peaceful activities,” the report said, in unusually blunt language. Tehran insisted that it had the right to vet inspectors and turn them away.

The standoff continued for the next few years. In November 2011, the IAEA Board of Governors adopted a resolution expressing “deep and increasing concern about the unresolved issues regarding the Iranian nuclear program, including those which need to be clarified to exclude the existence of possible military dimensions.” The resolution urged Iran to comply with its nuclear-related obligations under the U.N. Security Council.

One year later, IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano told the U.N. General Assembly that efforts to engage Iran had not yielded “concrete results” and that the IAEA could not “conclude that all nuclear material in Iran is in peaceful activities.”

The IAEA confirmed that Iran was continuing to enrich uranium, add to its stockpile, upgrade facilities, and build a heavy water reactor. U.N. inspectors alleged that Iran had “sanitized” the Parchin military site, making it difficult to investigate possible military dimensions of its nuclear program. Throughout 2012, the United States and European Union expanded sanctions on Iran.

Nuclear talks

A turning point came in late 2013, as the world’s six major powers began negotiations with Iran over its nuclear program. On November 11, Amano visited Tehran and met with Ali Akbar Salehi, head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Agency. They signed the Framework for Cooperation Agreement, which called for Tehran to provide the IAEA greater information and access relating to:

- The Gchine mine in Bandar Abbas

- The Heavy Water Production Plant near Arak

- All new research reactors

- The identification of 16 sites designated for the construction of nuclear power plants

- Iran’s announcements about additional enrichment facilities

- Laser enrichment technology

On November 24, negotiators reached an interim agreement to constrain Tehran’s nuclear program in exchange for limited sanctions relief. Iran pledged to neutralize its stockpile of enriched uranium, cease enrichment above five percent, stop installing additional centrifuges, and halt construction on the Arak heavy water reactor.

The agreement, known as the Joint Plan of Action, entered into force on Jan. 20, 2014. The same day, the IAEA issued a report stating that Iran had begun complying with its terms. The United States and European Union began waiving certain sanctions and preparing to release Iran’s oil money frozen overseas.

In March, Amano announced that Iran had implemented the six measures required by the Framework for Cooperation Agreement. But he added that “much remains to be done to resolve all outstanding issues.”

The final nuclear deal

After more than 18 months of negotiations, Iran and the world’s six major powers reached a final comprehensive nuclear deal on July 14, 2015, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

The IAEA will play a critical role in implementing the deal. The agency is responsible for monitoring Iran’s compliance with nuclear-related measures, which will determine the timing of sanctions relief.

Before the deal is implemented, the IAEA must confirm that Iran:

- Reduced its supply of excess heavy water and halted construction on the Arak reactor

- Reduced its capacity to 5,060 centrifuges, enrichment levels to 3.67 percent, and its uranium stockpile to 300 kg

- Ceased enrichment activity at Fordo

- Is conducting R&D within the parameters specified by the JCPOA

- Notified the IAEA that it has provisionally applied the Additional Protocol

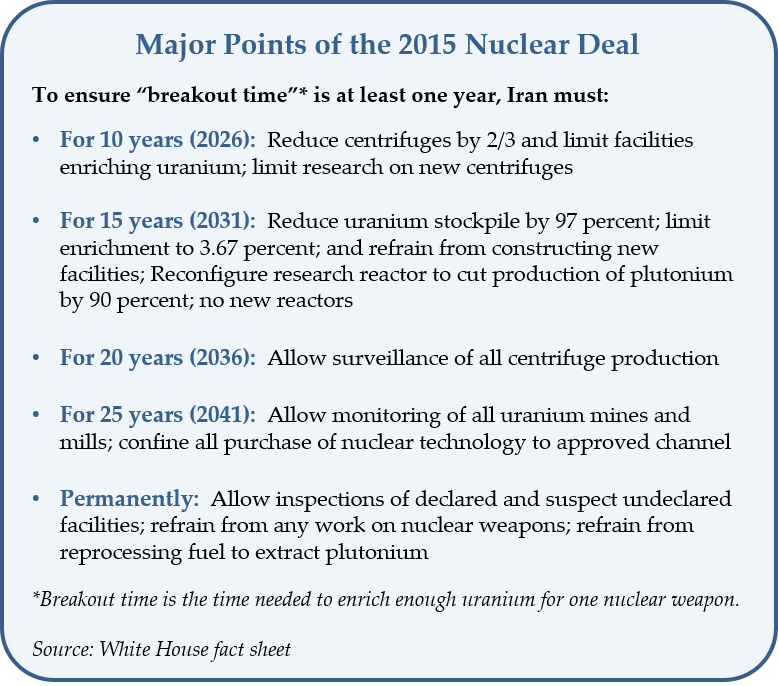

The IAEA will continue to oversee Iran’s compliance for the duration of the deal, according to the following timeline.

The deal also contained measures to improve Iran’s transparency with the IAEA.

First, Iran agreed to implement the Additional Protocol – a set of provisions that enhance the IAEA’s ability to gather information on a state’s nuclear activities and sites. While Iran’s nuclear restrictions under the JCPOA will be phased out over time, the Additional Protocol will remain in force indefinitely. Under the deal, Iran is required to provisionally apply the protocol on the deal’s adoption day, set to occur in October 2015.

Second, the deal refined the IAEA’s mechanism to resolve allegations of undeclared nuclear sites and materials. Although the Additional Protocol allows U.N. inspectors to investigate clandestine activities, the JCPOA further specifies that these issues must be resolved in a 24-day period.

According to the deal, Iran and the IAEA have 14 days to agree upon a way to address allegations of undeclared sites. If they cannot, the matter is referred to the Joint Commission – a body consisting of members from Iran and the world’s six major powers tasked with overseeing the deal’s implementation. The commission’s consultation process cannot exceed seven days, and Iran would then have three days to comply with any necessary measures.

Third, the deal stipulated that Iran must comply with the IAEA’s requests for information about the possible military dimensions (PMDs) of its nuclear program, as specified in the “Roadmap for Clarification of Past and Present Outstanding Issues.” (The IAEA spelled out its specific concerns related to PMDs in the annex of this 2011 report).

Amano and Salehi agreed to the roadmap on July 14, the same day as the final nuclear deal. The IAEA announced on October 15 that the activities set out in the roadmap had been completed. Amano aimed to complete a final assessment by December 2015.

On Sept. 21, 2015, Amano announced there had been “significant progress” in implementing the roadmap after meeting with Iranian officials in Tehran. Amano visited the Parchin military base for the first time, emphasizing that the site was “important in order to clarify issues related to possible military dimensions.” Inspectors had been denied access to the site in 2012.

Factoids

- The IAEA was founded in 1957 as a direct result of the U.S. “Atoms for Peace” initiative to spread peaceful nuclear technology and stop the proliferation of atomic weapons. It has 165 member states.

- Iran had no centrifuges turning in 2003, when the IAEA investigation began. By August 2010, it had 3,772 centrifuges enriching uranium and 5,084 more installed but not yet enriching, according to an IAEA report.

- In August 2015, the IAEA reported that Iran had 16,428 centrifuges installed at Natanz and 2,710 installed at Fordo. The nuclear deal requires Iran to reduce its number of centrifuges to 6,104 -- 5,060 of which will be permitted to enrich uranium – for 10 ten years. The excess centrifuges will be placed under continuous IAEA monitoring.

- As of June 2015, 126 states had implemented the Additional Protocol. Iran was one of 20 states that had signed the protocol, but not brought it into force – the step required to make it legally binding for the state.

Trendlines

- Even under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s controversial presidency, Tehran wanted to maintain at least minimal cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency, since kicking out all inspectors could have led to a harsher international response, including more severe sanctions and even military strikes.

- The extent of international inspectors’ access to Iranian facilities – particularly military sites – was a key sticking point during the nuclear talks. If the deal is fully implemented, the IAEA will have greater access to information about Iran’s nuclear program for at least the next two decades.

- The Islamic Republic is likely to continue to insist its nuclear program is strictly for peaceful nuclear energy, even if other secret sites or work are uncovered.

Timeline of the IAEA and Iran

The following are summaries of reports and updates by the International Atomic Energy Agency on Iran’s nuclear program since January 2016, when the nuclear deal went into its implementation phase.

Jan. 16, 2016: IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano confirmed that Iran had taken the necessary steps to start implementation of the nuclear deal, also known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Inspectors on the ground verified that Tehran reduced its enriched uranium stockpile, cut and capped its capacity to enrich uranium, modified the Arak heavy water rector to block its ability to produce plutonium, and allowed more robust monitoring by the IAEA.

Feb. 26, 2016: The IAEA’s first quarterly report on Iran’s nuclear program following implementation noted that Iran briefly exceeded the 130 metric ton limit on its heavy-water stockpile. Tehran, however, reduced the 130.9 tons back below the limit by shipping out 20 metric tons. The report was short but detailed Iran’s compliance with specific aspects of the deal.

May 27, 2016: The IAEA report to the Board of Governors found that Iran was living up to its commitments under the nuclear deal. The watchdog said that Iran accepted additional inspectors and provided complementary access to sites and facilities under the Additional Protocol.

Sept. 8, 2016: The IAEA report to the Board of Governors found that Iran was living up to its commitments under the nuclear deal. For example, Iran had not surpassed limits on its stock of enriched uranium or heavy water. As with earlier quarterly reports, however, this one did not include details about every restriction in JCPOA.

Nov. 17, 2016: The IAEA report found that while Iran was in general compliance with its obligations, the country’s stocks of heavy water had exceeded the limit by 0.1 metric tons. Iran, however, informed the IAEA of its plan to ship it out of the country.

Jan. 19, 2017: IAEA Director General Amano and U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz confirmed that Iran had removed certain infrastructure and excess centrifuges from the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant by the one-year anniversary of implementation, as required under the nuclear deal.

Feb. 24, 2017: The Director General’s report found that Iran was complying with the JCPOA. The report said that Tehran was not continuing construction of its heavy water research reactor at Arak. Iran’s stockpile of low-enriched uranium —which can be used for peaceful purposes but could also be reprocessed for use in a weapon —was 101.7 kilograms, well below the 300-kilogram limit. Earlier in 2017, Iran had reportedly come close to reaching the limit before a large amount stuck in pipes was recategorized as unrecoverable.

May 9, 2018: Director General Amano said Iran “is subject to the world’s most robust nuclear verification regime under the JCPOA, which is a significant verification gain.” In a statement, he asserted that “the IAEA can confirm that the nuclear-related commitments are being implemented by Iran.”

June 2, 2017: The IAEA report’s findings indicated that Iran was complying with the JCPOA. Tehran’s stockpile of low-enriched uranium was 79.8 kilograms, less than in the previous report and well below the 300-kilogram limit. The report, however, did not include any details about how the IAEA was confirming that Iran was not undertaking certain activities related to weaponization.

Aug. 31, 2017: The IAEA reported that Iran was complying with the JCPOA. Director General Amano, however, rejected Tehran’s claim that its military sites were off-limits to inspectors. He told The Associated Press that his agency "has access to (all) locations without making distinctions between military and civilian locations" under the JCPOA.

Sept. 11, 2017: Amano reported to the IAEA Board of Governors that nuclear related commitments were being implemented. “The Agency continues to verify the non-diversion of nuclear material declared by Iran under its Safeguards Agreement. Evaluations regarding the absence of undeclared nuclear material and activities in Iran remain ongoing,” he said.

Nov. 13, 2017: The IAEA released its eighth verification report indicating Iranian compliance with the deal. Iran’s low-enriched uranium stockpile as of November 5 was 96.7 kg, more than what was reported previously but still well below the limit. Iran’s stock of heavy water was 114.4 metric tons, below the 130-ton limit.

Feb. 22, 2018: The IAEA released a quarterly report acknowledging Iran’s compliance with the JCPOA. It noted that Iran notified the watchdog of a “decision that has been taken to construct naval nuclear propulsion in future.” Iranian leaders have previously mentioned that goal, which would increase Iran’s naval power and could involve enriching uranium beyond the limits of the nuclear deal.

May 24, 2018: The IAEA released a quarterly report, the first since the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal, showing Iranian adherence to the JCPOA. The watchdog found that Iran’s stockpile of heavy water remained below the agreed limit of 130 tons during the previous three months. Iran had slightly exceeded that limit twice since the JCPOA went into effect. It noted that Tehran was implementing the Additional Protocol, which provides the watchdog with great access to nuclear sites. But the report also suggested that “proactive cooperation by Iran in providing such access would facilitate implementation of the Additional Protocol and enhance confidence.”

Aug. 30, 2018: The IAEA released a quarterly report indicating Iranian compliance with the nuclear deal. The watchdog was able to carry out all necessary inspections. “Timely and proactive cooperation by Iran in providing such access facilitates implementation of the Additional Protocol and enhances confidence,” said the report.

Sept. 10, 2018: In his introductory statement to the IAEA Board of Governors, Director General Amano said Iran was implementing its commitments under the JCPOA. “It is essential that Iran continues to fully implement those commitments,” he added.

Nov. 12, 2018: The IAEA’s quarterly report noted that Iran was complying with the JCPOA. The agency said it had access to all the necessary sites and that Iran’s heavy water and low-enriched uranium stockpiles remained within the limits.

Feb. 22, 2019: The IAEA again found that Iran was complying with the JCPOA. Much of the language matched that of the previous quarterly report. “Timely and proactive cooperation by Iran in providing such access facilitates implementation of the Additional Protocol and enhances confidence,” stated the IAEA. On March 4, Amano confirmed that Iran “is implementing its nuclear commitments.”

May 31, 2019: An IAEA safeguards report found that Iran was in compliance with the JCPOA. But it also noted that Tehran’s stockpiles of low-enriched uranium and heavy water were growing. It also raised questions about whether Iran potentially overstepped limits on advanced centrifuge installation. It had installed 33, more than the maximum of 30, according to one interpretation of the JCPOA. On June 10, Amano said “the [uranium] production rate is increasing,” but he did not provide further details. He added that he was “worried about increasing tensions over the Iranian nuclear issue.”

Aug. 30, 2019: An IAEA safeguards report confirmed that Iran had begun to enrich uranium to 4.5 percent, beyond the 3.67 percent limit stipulated in the JCPOA. The agency also verified that Iran’s stockpile of low-enriched uranium exceeded the 300 kg limit. Iran continued to adhere to other aspects of the deal and allowed inspectors access to all sites that they needed to visit. But the report implied that Iran’s cooperation could use improvement. “Ongoing interactions between the Agency and Iran...require full and timely cooperation by Iran. The Agency continues to pursue this objective with Iran,” said the report.

Sept. 25, 2019: The IAEA found that Iran had breached the JCPOA again by using advanced centrifuges to enrich uranium. The watchdog “verified that all of the (centrifuge) cascades already installed in R&D lines 2 and 3 ... were accumulating, or had been prepared to accumulate, enriched uranium.” Each cascade could include up to 20 centrifuges. The JCPOA only allowed Iran to use some 5,000 of its first-generation IR-1 centrifuges to enrich uranium. Advanced centrifuges were supposed to only be used in small numbers for research purposes.

Nov. 11, 2019: In a quarterly report, the IAEA said that Iran had breached the 2015 nuclear deal by increasing its stockpile of enriched uranium. The watchdog also reported that its inspectors had found traces of uranium “at a location in Iran not declared to the agency.” The IAEA confirmed Iran had started enriching uranium at the underground Fordo facility. The JCPOA had banned uranium enrichment at the site until 2031.

Nov. 18, 2019: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had breached the 130 metric ton limit on heavy water set by the JCPOA. Heavy water allows unenriched uranium to be used as a fuel in specially designed nuclear reactors. Heavy water reactors also produce plutonium as a waste fuel, which can then be reprocessed for use in plutonium bombs.

March 3, 2020: The IAEA released two reports that criticized Iran for violations of the JCPOA. Iran had tripled its stockpile of low- enriched uranium over the previous three months, it said in one report. It shortened the breakout time to produce enough fissile material for a nuclear weapon, although the IAEA did not find evidence that Iran had taken steps to produce a bomb. In the second report, the IAEA condemned Iran’s refusal to grant inspectors access to three sites of interest. The report said that it found evidence from early July 2019 that was consistent with efforts to “sanitize” part of an unnamed location to obscure nuclear material.

March 3, 2020: The IAEA said that Iran had refused to grant inspectors access to three sites of interest. The sites were suspected to have been part of the Iran’s nuclear program in the early 2000s. The watchdog believed that Iran had tried “to sanitize part of the location” to obscure its past nuclear activities. “Iran is curtailing the ability of the agency to do its work,” IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi said.

June 5, 2020: The IAEA said that Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium had grown far above the amount permitted by the JCPOA. Iran possessed 1,571.6 kg of low enriched uranium, a 50 percent increase since February. Its stockpile of heavy water remained slightly above the 130 metric ton limit set by the JCPOA.

June 5, 2020: Iran blocked IAEA inspectors from accessing two sites, the U.N. watchdog reported. The agency said that the sites may have been used for the storage and explosive testing of undeclared nuclear materials in the early 2000s. “The Agency notes with serious concern that, for over four months, Iran has denied access to the Agency…to two locations and, for almost a year, has not engaged in substantive discussions to clarify Agency questions related to possible undeclared nuclear material and nuclear-related activities in Iran,” the report said.

June 19, 2020: The IAEA Board of Governors passed a resolution—25 to two, with seven abstentions—calling on Iran to fully cooperate with an investigation into its past nuclear work after more than a year of stonewalling. Iran had denied inspectors access to two suspect sites where it was suspected of storing undeclared nuclear material The resolution was the first formal challenge of Iran in eight years from the IAEA Board of Governors.

Aug. 26, 2020: The IAEA and Iran released a joint statement which said that Iran agreed to provide the IAEA with access to the two suspect sites and facilitate verification activities.

Sept. 4, 2020: In a quarterly report, the IAEA said that Iran’s stockpile of low-enriched uranium reached 2,105 kilograms, or about 10 times more than the JCPOA limit. The stockpile had grown some 544 kilograms since the last quarterly report, released in June. Iran also began operating slightly more advanced centrifuges, but not enough shorten its breakout time, which remained three to four months. When Iran was in full compliance with the JCPOA, its breakout time had been 12 months.

In a separate safeguards report, the U.N. watchdog confirmed that it had visited one undeclared nuclear site to take environmental samples. The agency said it would visit another suspect site later in September.

Nov. 11, 2020: The IAEA reported that Iran’s stockpile of low-enriched uranium reached 2,443 kg (2.7 tons), or about 12 times more than the JCPOA limit. The stockpile had grown by 337.5 kg since the prior report released in September, a slower rate of growth than previously recorded. Iran installed 174 IR-2M centrifuges and conducted tests of three IR-4 advanced centrifuges.

The IAEA found Iran’s explanations for uranium particles detected at an undeclared nuclear site to be “unsatisfactory” and “not technically credible.”

Nov. 17, 2020: The IAEA reported that Iran began feeding uranium gas into 174 IR-2M advanced centrifuges at Natanz, the IAEA .

Dec. 4, 2020: Iran informed the IAEA that it would install three new cascades of advanced centrifuges. Each cascade was made up of more than 150 centrifuges.

Jan. 4, 2021: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had begun enriching uranium up to 20 percent at Fordo. The agency verified that centrifuges cascades at Fordo had been reconfigured to enrich levels of uranium from 4.1 percent to 20 percent.

Feb 2, 2021: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had completed installation of 174 more IR-2M centrifuges at Natanz and began feeding uranium gas into them. In total, Iran was enriching uranium with 5060 IR-1 centrifuges and 348 IR-2M centrifuges at Natanz.

Feb. 10, 2021: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had enriched 3.6 grams of natural uranium metal. Iran would need 500 grams of highly enriched uranium metal for a nuclear weapon core.

Feb. 17, 2021: Iran informed the IAEA that it would install two new cascades of advanced centrifuges at Natanz. Each cascade had 174 IR-2M centrifuges and would enrich uranium up to 5 percent.

Feb. 19, 2021: The IAEA detected uranium particles at two sites that may have been used for the storage and testing of undeclared nuclear materials in the early 2000s. Iran had previously blocked access to the sites for seven months before granting the IAEA access in August 2020, which called its commitment to transparency into question. Tehran had a secret nuclear weapons program until 2003, when it was disbanded, according to U.S. intelligence.

Feb. 21, 2021: The IAEA and Iran agreed on an compromise that would provide the nuclear watchdog less access to the country's declared and undeclared nuclear sites. Under the arrangement, the nuclear watchdog could not access cameras installed at declared nuclear sites but Iran will be required to save all surveillance footage for three months. If the United States lifts sanctions on Iran, Tehran will hand over the tapes to the IAEA. If the Biden administration does not lift punitive economic measures, the footage “will be deleted forever," the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran said. IAEA Director General Grossi called it a “temporary solution” that “salvages the situation.”

Feb. 23, 2021: Iran suspended compliance with the Additional Protocol, a voluntary agreement that grants inspectors “snap” inspections and was part of the 2015 nuclear deal negotiated with the world’s six major powers. But Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that the step, and all other breaches of the deal, was "reversible" if the Biden administration lifted sanctions.

Mar. 1, 2021: Iran had failed to provide a "necessary, full and technically credible explanation" for the presence of uranium particles at undeclared sites, IAEA chief Rafael Grossi told the Board of Governors. "The Agency is deeply concerned that undeclared nuclear material may have been present at this undeclared location and that such nuclear material remains unreported by Iran under its Safeguards Agreement," he said.

Mar. 8, 2021: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had begun feeding uranium gas into a third cascade of advanced centrifuges at Natanz, Reuters reported. A fourth cascade of IR-2M centrifuges was installed but not enriching uranium, while installation of a fifth cascade was ongoing. Each cascade had 174 IR-2M centrifuges.

Mar. 15, 2021: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had begun enriching uranium at Natanz with IR-4 centrifuges. The IR-4 was the second type of advanced centrifuge, after the IR-2M, operating at the Natanz facility.

Apr. 1, 2021: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had begun enriching uranium with a fourth cascade of 174 IR-2M centrifuges. Iran was now using a total of 696 IR-2M centrifuges at Natanz.

April 7, 2021: Iran and the IAEA delayed talks in Tehran originally scheduled for early April. IAEA Director General Grossi told Newsweek that the agency planned to ask Iran questions about uranium participles discovered at undeclared sites.

April 8, 2021: Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi met with IAEA Director General Grossi while in Vienna. Araghchi said that the IAEA would play an "important role" in verification if Iran came to an agreement with the world powers over returning to compliance with the JCPOA. He added that Iran would engage with the IAEA "in good faith" about outstanding nuclear issues, such as the discovery of uranium particles at undeclared sites. "I am confident we are able to resolve those questions as soon as possible," he told Press TV.

April 10, 2021: Iran began testing its most advanced nuclear centrifuge, the IR-9, at the Natanz enrichment site. Under the nuclear deal, Iran could only operate 5,060 first-generation IR-1 centrifuges until 2025. The IR-9 can enrich uranium 50 times faster than the IR-1.

April 13, 2021: Iran told the IAEA that it will begin enriching uranium to 60 percent, the highest level of enrichment that it has publicly acknowledged. The move would be a major breach of the 2015 nuclear deal and brought Tehran closer to having weapons grade uranium. Iran also planned to install 1,000 additional centrifuges at Natanz.

April 14, 2021: The IAEA said that Iran "had almost completed" preparations to enrich uranium up to 60 percent. The agency also reported that Iran would install 1,024 IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz, which had been hit by an explosion three days earlier. Kazem Gharibabadi, the Iranian ambassador in Vienna, called the sabotage at Natanz a "gross violation" of international law. "The international community must strongly condemn this act of nuclear terrorism and hold the culprits and their accomplices accountable," he wrote in a letter to Grossi.

April 19, 2021: The IAEA and the Iranian government began expert-level talks in Vienna over uranium particles discovered by the nuclear watchdog at undeclared sites in Iran. The talks were aimed at "clarifying outstanding safeguards issues," the IAEA said.

April 21, 2021: Iran installed more advanced centrifuges at the Natanz nuclear facility, the IAEA reported. Iran now had a total of 1,044 IR-2M centrifuges and 348 IR-4 centrifuges installed at Natanz.

April 22, 2021: The IAEA said that Iran was using fewer centrifuges to produce highly enriched uranium gas. Initially, Iran was using one cascade of IR-4 centrifuges and one cascade of IR-6 centrifuges to enrich uranium up to 60 percent. It converted the IR-4 centrifuges to instead enrich uranium up to 20 percent, the nuclear watchdog reported.

May 11, 2021: Iran has enriched uranium to 63 percent, the IAEA reported. The level of enrichment was "consistent with the fluctuations of the enrichment levels (described by Iran)," the agency told member states.

May 24, 2021: Iran and the IAEA extended a deal to retain surveillance footage at declared nuclear sites by one month. The agreement would expire on June 24, less than a week after Iran's presidential election on June 18. The extension was designed to give more time for negotiations in Vienna to bring Iran and the United States back into compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal. "I recommend that they use this opportunity, which has been provided in good faith by Iran, and lift all the sanctions in a practical and verifiable manner," Ambassador Kazem Gharibabadi, Iran's representative to the U.N. watchdog, said.

May 31, 2021: The IAEA said that Iran had failed to provide a "necessary explanation" for the presence of uranium particles at three undeclared sites previously inspected by the agency. "The lack of progress in clarifying the Agency's questions concerning the correctness and completeness of Iran's safeguards declarations seriously affects the ability of the Agency to provide assurance of the peaceful nature of Iran's nuclear program," the U.N. nuclear watchdog said in a report to member states. The IAEA estimated that Iran had 3,241 kilograms of enriched uranium, an increase of 273 kg since the last quarterly report. The estimate was the smallest increase in Iran's nuclear stockpile since August 2019.

June 7, 2021: Iran had made no "concrete progress" in explaining the presence of uranium particles at three undeclared sites, the head of the U.N.'s nuclear watchdog reported. Tehran's refusal to answer questions from inspectors "seriously affects the ability of the agency to provide assurance of the peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear program,” Director General Grossi told the IAEA's board of governors. "The Iranian government has reiterated its will to engage and to cooperate and to provide answers, but they haven’t done that so far," he added.

June 15, 2021: Iran has produced 6.5 kg (14 lbs) of 60 percent enriched uranium, the government reported. The country also was on track to produce more uranium enriched to 20 percent than required by a law passed by Parliament in December. “The Atomic Energy Organization was supposed to produce 120 kg (265 lbs) of 20 percent enriched uranium in a year," spokesperson Ali Rabiei said. "According to the latest report, we now have produced 108 kg (238 lbs) of 20 percent uranium in the past five months."

June 23, 2021: Iran said that it would allow its monitoring deal with the IAEA to expire on June 24 before deciding whether to extend it. "After the expiration of the agreement's deadline, Iran's Supreme National Security Council (will) decide about the agreement's extension at its first meeting," presidential chief of staff Mahmoud Vaezi said.

June 24, 2021: Iran's monitoring agreement with the IAEA expired.

June 25, 2021: The U.N. nuclear watchdog demanded an "immediate response" from Iran on whether it would retain data collected at declared nuclear sites. Iran had yet to respond to the agency's questions, Grossi told the IAEA's board of directors.

Secretary of State Blinken warned that expiration of the IAEA's monitoring agreement could complicate efforts to revive the 2015 nuclear deal. "The concern has been communicated to Iran and needs to be resolved," he told reporters in Paris.

July 6, 2021: Iran started the process to produce enriched uranium metal, the IAEA reported. Iran planned to use the metal, which would be enriched to 20 percent, to produce fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor. But uranium metal can also be used to make a nuclear weapon core, which is why the JCPOA prohibited uranium metal production. Iran had produced a small amount of uranium metal in February 2021, but it was not enriched.

The United States called the move “another unfortunate step backwards.” Britain, France and Germany said it was a “serious violation” of the JCPOA. “Iran has no credible civilian need for uranium metal R&D (research and development) and production, which are a key step in the development of a nuclear weapon,” the Europeans said in a joint statement.

Aug. 14, 2021: The IAEA reported that Iran had produced 200 g (0.44 lbs) of uranium metal enriched up to 20 percent. The metal would be used to fuel the Tehran Research Reactor, Iran previously claimed. But the metal could also be used to produce the core of a nuclear weapon.

Aug. 16, 2021: The State Department condemned Iran's increased production of uranium metal. "Iran has no credible need to produce uranium metal, which has direct relevance to nuclear weapons development," spokesman Ned Price said. Price warned that further breaches of the 2015 nuclear deal "will no provide Iran negotiating leverage" and "will only lead to Iran's further isolation."

Aug. 17, 2021: Iran was using a second cascade of centrifuges to enrich uranium to nearly weapons-grade level, the IAEA reported. Tehran added a cascade of 153 advanced IR-4 centrifuges to enrich uranium up to 60 percent, according to a report by the U.N. nuclear watchdog. Uranium needs to be enriched up to 90 percent to fuel a nuclear bomb.

In April, began enriching uranium to 60 percent, the highest level of enrichment that it has publicly acknowledged. In May, the IAEA reported that Iran was using 164 IR-6 centrifuges to enrich uranium up to 60 percent.

Aug. 19, 2021: Britain, France and Germany expressed “grave concern” over Iran’s production of uranium metal enriched to 20 percent and enrichment of uranium to 60 percent. “Both are key steps in the development of a nuclear weapon and Iran has no credible civilian need for either measure,” foreign ministers from the European powers said in a joint statement. “Our concerns are deepened by the fact that Iran has significantly limited IAEA access” to nuclear sites, they added. The ministers also warned that Iran’s moves made a return to the JCPOA “more complicated.”

Sept. 12, 2021: Iran and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reached an agreement that would allow the watchdog agency to service monitoring equipment at Iranian nuclear facilities. The IAEA had not had access to its equipment, including cameras, since May 25. It urgently needed to swap out memory cards to prevent any data gaps.

The new arrangement “is indispensable for us to provide the necessary guarantee and information to the IAEA and to the world that everything is in order,” IAEA Director General Grossi said on September 12. He brokered the temporary deal with Mohammad Eslami, the head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), during a day trip to Tehran.

Sept. 23, 2021: The IAEA announced that inspectors had been denied entry to the centrifuge manufacturing plant at the Karaj facility near Tehran. The agency said the incident was a violation of the deal made brokered on September 12. “The Director General reiterates that all of the agency’s activities referred to in the joint statement for all identified agency equipment and Iranian facilities and locations are indispensable in order to maintain continuity of knowledge,” the IAEA stated.

Oct. 23, 2021: The IAEA monitoring program in Iran is “no longer intact,” Grossi, warned in an interview with NBC News. Iran has not allowed the watchdog to repair cameras that monitor centrifuge production at the Tesa Karaj facility outside Tehran. Iran has alleged that Israel sabotaged in an explosion at the Tesa Karaj facility in June. One camera was damaged, and another was destroyed.

Iran’s decision to limit IAEA access “hasn’t paralyzed what we are doing there, but damage has been done, with a potential of us not being able to reconstruct the picture, the jigsaw puzzle,” Grossi said. If and when the JCPOA is restored, the world’s six major powers will need to understand the status of Iran’s program, he added.

Nov. 17, 2021: In a report, the IAEA said that Iran had twice turned back inspectors at a facility that manufacturers parts for centrifuges used to enrich uranium. The facility in Karaj, outside Tehran, may be again manufacturing parts for advanced centrifuges. Since February 2021, IAEA had been unable to inspect the site because of a law passed in December 2020 curtailing access for inspectors. The IAEA also reported that 170 advanced IR-6 centrifuges had been installed at the underground facility at Fordow since September.

Nov. 23, 2021: Grossi traveled to Tehran to try and resolve the access dispute. "The agency is seeking to continue and deepen the dialogue with the government of Iran,” Grossi said at a press conference. “We agreed to continue our joint work on transparency and this will continue." He later described the trip as constructive but inconclusive.

Dec. 14, 2021: Grossi warned that the IAEA did not have a clear picture of Iran’s nuclear program. “If the international community through us, through the IAEA, is not seeing clearly how many centrifuges or what is the capacity that they may have ... what you have is a very blurred image,” Grossi told the Associated Press. “It will give you the illusion of the real image. But not the real image. This is why this is so important.” Grossi called on Iran to allow the IAEA to replace damaged cameras in the Karaj centrifuge manufacturing workshop.

Dec. 15, 2021: The IAEA and Iran reached an agreement to allow IAEA to replace surveillance cameras at the Karaj facility that produces parts for centrifuges. Centrifuges are machines that spin uranium gas at high speeds to produce fuel for nuclear reactors or weapons. Yet the deal was only a partial solution to a potential crisis. The compromise would still prevent the IAEA from actually seeing what is on the cameras—or knowing the status of Iran’s technological advances since February 2021. Experts have been increasingly concerned about a possible “sneakout” in Iran’s nuclear program because inspectors have had limited access.

Jan. 31, 2022: Iran had moved its centrifuge manufacturing workshop from Karaj to Isfahan, the IAEA reported.

March 5, 2022: Iran agreed to provide written explanations in response to IAEA questions by March 20. The IAEA committed to reporting conclusions about the investigation by the June 2022 Board of Governors meeting.

April 6, 2022: Iran's nuclear chief, Mohammad Eslami, said that Iran had provided documents on outstanding issues to the IAEA on March 20. “They are reviewing those documents and probably the agency's representatives will travel to Iran for further talks and then the IAEA will present its conclusion.” Tehran had previously missed multiple deadlines to provide the IAEA with answers.

May 10, 2022: IAEA Director General Grossi said that Iran “has not been forthcoming” with information about undeclared sites where the IAEA found traces of uranium. “We are extremely concerned about this,” he told a European Parliament committee. Iran “should be at the top of our preoccupations in spite of the drama that is unfolding in Ukraine.”

May 30, 2022: Iran had stockpiled more than 18 times the amount of enriched uranium allowed under the 2015 nuclear deal, an unprecedented advance, according to a leaked report by the U.N. nuclear watchdog. The growing stockpile meant that Iran could amass sufficient fuel for a single nuclear bomb in a few weeks, although experts claimed that the so-called “breakout time” had decreased to a mere 10 days—or less. “This idea of crossing the line, it’s going to happen,” Director General Grossi, told reporters on June 6. “Having a significant quantity [of highly enriched uranium] does not mean having a bomb,” he said. “Iran can stop, through negotiations, or they themselves can decide to slow down.”

June 8, 2022: The IAEA’s Board of Governors, led by the United States, Britain, France, and Germany, passed a resolution criticizing Iran over unexplained traces of uranium. The resolution expressed “profound concern” that Iran had not provided credible or accurate information on uranium traces found at three locations not declared by the government “despite numerous interactions” with the IAEA. The resolution passed 30 to 2, with three abstentions. Russia and China, which have veto power at the U.N. Security Council, opposed the resolution. India, Pakistan and Libya abstained.

Iran “deplored” the resolution and retaliated by removing 27 cameras that monitor various aspects of its nuclear activities under provisions of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). It also moved to install two cascades of advanced centrifuges IR-6 centrifuges in Natanz, which is Iran’s biggest facility for uranium enrichment.

July 22, 2022: IAEA Director General Grossi warned that Iran’s nuclear program was “galloping ahead” while the IAEA had “very limited visibility.” If the JCPOA is restored, “it is going to be very difficult for me to reconstruct the puzzle of this whole period of forced blindness,” he said in an interview.

July 25, 2022: Iran’s nuclear chief, Mohammad Eslami, said that IAEA monitoring cameras would remain off until the 2015 nuclear deal was restored. He also refused to respond to the agency’s questions about the uranium traces. "The claimed PMD (possible military dimensions) cases and locations were closed under the nuclear accord and if they (West) are sincere, they should know that closed items will not be reopened,” Eslami said.

Aug. 2, 2022: IAEA Director General Grossi warned that Iran’s nuclear program was “moving ahead very, very fast and not only ahead, but sideways as well, because it's growing in ambition and in capacity.” He criticized Tehran for not being transparent and compliant.

Aug. 3, 2022: Iran had installed three cascades of advanced IR-6 centrifuges at the Natanz fuel enrichment plant, according to an IAEA report. Tehran had also told the agency that it planned to install six IR-2m cascades at the site.

Aug. 22, 2022: IAEA Director General Grossi pledged to not halt its probe into unexplained uranium traces in Iran. “This idea that politically we are going to stop doing our job is unacceptable for us,” Grossi told CNN. “We want to be able to clarify these things. So far Iran has not given us the technically credible explanations we need to explain the origin of many traces of uranium, the presence of equipment at places.”

Aug. 29, 2022: Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi stipulated that Iran would only agree to restore the 2015 nuclear deal if the IAEA closed the investigation into traces of uranium found at undeclared sites. “Without resolving safeguards issues, talking about an agreement would be meaningless,” Raisi said.

Sept. 7, 2022: The IAEA reported that Iran had accumulated enough uranium enriched to 60 percent that, if enriched further to 90 percent, could fuel one bomb. The JCPOA had capped Iran’s enrichment at 3.57 percent. The watchdog also said that it could not “provide assurance that Iran’s nuclear programme is exclusively peaceful” because Tehran failed to cooperate with an investigation into past activities at undeclared sites.

Sept. 14, 2022: One-third of the 175 member states of the IAEA urged Iran to explain traces of uranium at three undeclared sites that date back to a covert program before 2003. In a joint statement, the 56 countries reiterated support for a resolution passed by the IAEA Board of Governors on June 8. The United States, Britain, France and Germany organized the statement because Iran had not provided the agency with the requested information during the three months between quarterly meetings.

Sept. 26, 2022: IAEA Director General Grossi tweeted that the IAEA and Iran had restarted dialogue regarding safeguards issues after he met with Iran’s nuclear chief, Mohammad Eslami, at the agency’s general conference.

Oct. 10, 2022: Iran had installed one cascade of advanced IR-4 centrifuges and six of IR-2m centrifuges at the Natanz fuel enrichment plant, according to a leaked IAEA report. Tehran had also informed the agency of plans to install three cascades of advanced centrifuges at the same site.

May 31, 2023: Tehran’s stockpile of 60-percent enriched uranium had grown to 114.1 kilograms (251 pounds), a 25 percent increase since February 2023, according to an IAEA report circulated to member states. The uranium could be enriched to 90 percent, or weapons grade, quickly, if Iran made the political decision to produce a bomb.

But Tehran also expanded cooperation with the U.N. nuclear watchdog by granting permission for it to install cameras at the centrifuge production facility in Isfahan, according to a second report. Centrifuges are cylindrical machines that enrich uranium by spinning at high speeds. Iran also allowed the installation of monitoring equipment at Fordo, a uranium enrichment facility buried under the mountains near Qom, and Natanz, another enrichment site. The IAEA also closed two probes. It had no further questions about uranium particles enriched to 83.7 percent that were discovered in January 2023. The IAEA also stopped its investigation into uranium traces found at Marivan, a site 325 miles southwest of Tehran allegedly connected to Iran’s pre-2003 nuclear weapons program.

Sept. 4, 2023: Iran slowed uranium enrichment to 60 percent, according to the IAEA. It enriched 7.5 kilograms (16.5 pounds) of uranium to 60 percent between June and August 2023. In the first half of 2023, Tehran enriched more than 50 kilograms of uranium to near weapons-grade. The IAEA added that Iran diluted 6.4 kilograms of 60 percent-enriched uranium to 20-percent enrichment. But the Islamic Republic increased its stockpile of uranium enriched to five and 20 percent and stalled negotiations over installing cameras at facilities. It also did not cooperate with an IAEA probe of undeclared nuclear material from 2019 and reportedly denied visas to agency inspectors.

Sept. 11, 2023: IAEA Director General Grossi expressed concern over a “decrease in interest” from IAEA member states in regard to Iran. “There is a certain routinization of what is going on there (in Iran) and I am concerned about this, because the issues are as valid today as they were before,” he warned in a press conference after the Board of Governors meeting.

Sept. 13, 2023: 63 IAEA member states called on Iran to cooperate with the U.N. nuclear watchdog in a joint statement. The group shared “the Director General’s regret that no progress has been made” in Iran’s implementation of a cooperation agreement with the IAEA. The countries called on Iran to address:

- “Outstanding safeguards issues in relation to nuclear material detected at undeclared locations in Iran,”

- “The discrepancy in the amount of nuclear material verified by the Agency at the Isfahan Uranium Conversion Facility,” and

- “Implementation of…the Safeguards Agreement, including the provision of the required early design information.”

Sept. 13, 2023: The United States, Britain, France and Germany called on Iran to cooperate with the U.N. nuclear watchdog and threatened a future resolution against Tehran. “If Iran fails to implement the essential and urgent actions contained in the November 2022 Resolution and the 4th March Joint Statement in full, the Board will have to be prepared to take further action in support of the (IAEA) Secretariat to hold Iran accountable in the future, including the possibility of a resolution,” the four countries said in a joint statement to the IAEA Board of Governors.

Nov. 15, 2023: Iran had accumulated enough highly enriched uranium that, if enriched further, could fuel three nuclear weapons, according to a quarlterly IAEA report from October 2023 seen by Reuters. Its stockpile of 60-percent enriched uranium grew by 6.7 kilograms (14.8 pounds) to 128.3 kilograms (282.9 pounds), although Iran had slowed down the rate of enrichment to 3 kilograms (6.6 pounds) per month. A separate report noted that Iran was still not cooperating with the IAEA on reinstalling monitoring equipment and other transparency issues.

Dec. 26, 2023: Iran had accelerated its enrichment of uranium to 60 percent purity, a technical step away from 90 percent purity or weapons-grade, according to an IAEA report. Iran was producing about nine kilograms (20 pounds) of uranium enriched to 60 percent per month. “These findings represent a backwards step by Iran and will result in Iran tripling its monthly production rate of uranium enriched up to 60%,” warned the United States, Britain, France, and Germany in a joint statement on December 28. “These decisions demonstrate Iran’s lack of good will towards de-escalation and represent reckless behavior in a tense regional context.”

Feb. 26, 2024: Iran’s overall stockpile of enriched uranium had grown 1,038.7 kilograms (2,289 pounds) to 5,525.5 kilograms (12,182 pounds) since the previous quarterly IAEA report. The agency noted that the stockpile of 60-percent enriched uranium had shrunk 6.8 kilograms (14.9 pounds) to 121.5 kilograms (267.8 pounds). But the proliferation risk remained. The Institute for Science and International Security estimated that Iran could make enough weapons-grade uranium “for seven nuclear weapons in one month, nine in two months, eleven in three months, 12-13 in four months, and 13 in five months.”

March 6, 2024: U.S. Ambassador Laura Holgate expressed serious concerns about Iran’s nuclear activities during the IAEA Board of Governors meeting in Vienna. “No other country today is producing uranium enriched to 60 percent for the purpose Iran claims and Iran’s actions are counter to the behavior of all other non-nuclear weapons states party to the NPT,” she said. The IAEA board “must be prepared to take further action should Iran’s cooperation not improve dramatically.”

In a joint statement, the E3 (Britain, France and Germany) also condemned Iran’s behavior. During the past five years, Iran has “pushed its nuclear activities to new heights” despite global sanctions, with levels of enrichment that are “unprecedented for a state without a nuclear weapons program.” IAEA Director General Grossi warned that the agency had “lost continuity of knowledge in relation to [Iran’s] production and inventory of centrifuges, rotors and bellows, heavy water and uranium ore concentrate.”

May 6-7, 2024: IAEA Director General Grossi visited Tehran to participate in a nuclear energy conference in Isfahan and speak with top officials. After returning to Vienna, Grossi said that he expected to “start having some concrete results soon” on Iran’s cooperation with an agreement made in March 2023 that would increase the monitoring of nuclear sites.

May 27, 2024: Iran had accumulated an additional 20.6 kilograms (45.4 pounds) of uranium enriched to 60 percent purity since the last IAEA quarterly report. Iran could produce enough fuel for three nuclear weapons if it further enriched its 142.1 kilograms (313.2 pounds) of uranium at 60 percent purity. Iran’s overall stockpile of enriched uranium grew 675.8 kilograms (1,489.8 pounds) to 6,201.3 kilograms (1,3671.5 pounds). The IAEA also did not report any progress on the investigation into manmade uranium particles found at two undeclared sites, Varamin and Turquzabad.

June 5, 2024: The IAEA’s 35-member board of governors censured Iran for failing to cooperate with the agency's investigation into unexplained uranium traces. Britain, France and Germany sponsored the resolution, which was also backed by the United States. The vote was 20 in favor, 12 abstentions and two against. Russia and China, which have veto power at the U.N. Security Council, were the only no votes. In a joint statement, Britain, France and Germany said that the resolution responded to “Iran’s persistent refusal to cooperate in good faith with the IAEA to clarify outstanding issues.” They urged Tehran to provide “technically credible explanations” for the undeclared nuclear material.

Photo credits: IAEA flag via Wikimedia Commons [public domain]; Natanz via Iranian President's Office and The New York Times; Rafael Grossi by IAEA Imagebank via Flickr [CC BY 2.0]; Yukiya Amano by IAEA Imagebank via Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0]; IAEA inspectors by IAEA Imagebank via Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0];