What was the state of Iran’s economy in March 2024 as the country celebrated the Persian New Year? What were the biggest economic challenges?

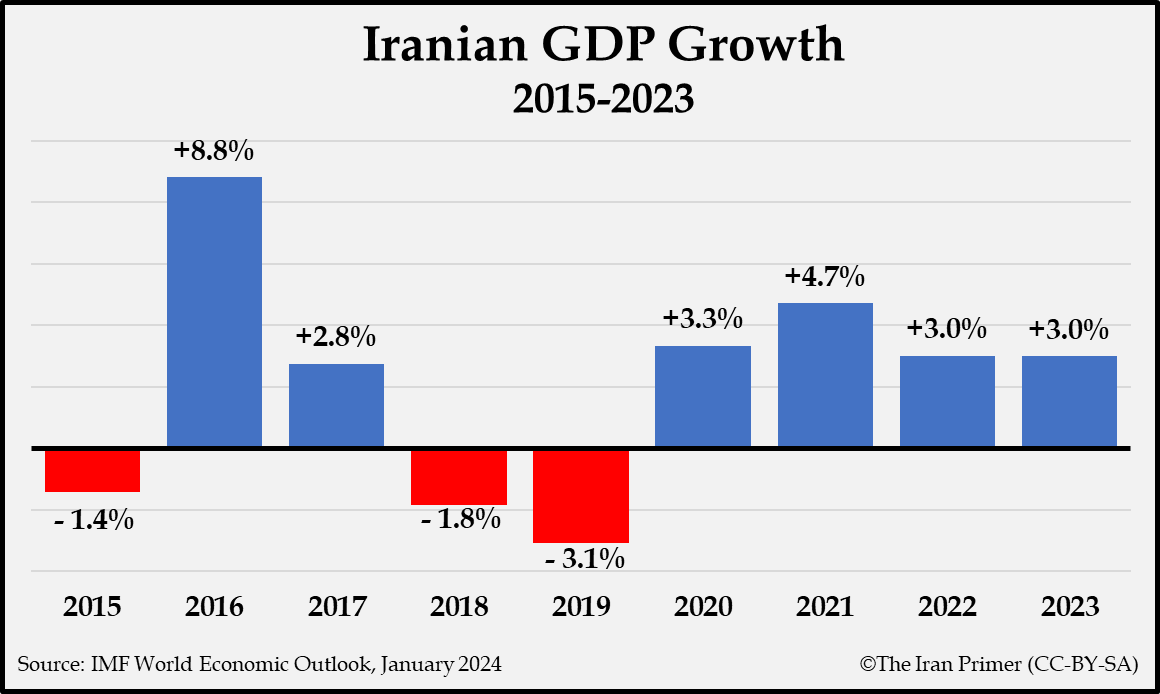

Sanctions have cast a long shadow on Iran’s economy, but they have not led to an economic collapse. Iran has managed to grow its overall economy by an average of 1.7 percent since the initial 2012 sanctions shock. But for ordinary Iranians, the government’s ability to “resist” sanctions for more than a decade represents a Pyrrhic victory. An economy that used to furnish ever-rising standards of living is no longer doing so.

Still, as the new year began, Iranian officials can at least boast that they have survived yet another year of “maximum pressure” sanctions imposed by the United States and its Western allies.

Except for a brief period of partial relief from 2016 to 2018, Iran has lived under a relatively harsh regime of sanctions since President Obama imposed them in 2012 in response to Tehran’s failure to meet its international nuclear obligations. President Trump reimposed strict sanctions in May 2018 and President Biden has continued and even expanded them up to the present day.

While the latest designations of individuals and entities across Iran’s defense industry, oil smuggling networks and law enforcement groups have not added meaningful additional economic pressure, all these actions have added to the sense that Iran’s economic isolation is a permanent condition.

The current situation stands in stark contrast to the period from the mid-1990s to 2012, when standards of living rose sharply for many ordinary Iranians. Over that period, per capita GDP (measured in terms of purchasing power parity) more than doubled from around $9,000 to $19,000.

But in early 2024, per capita GDP was only just recovering to its 2011 levels. Ordinary Iranians contended with high inflation, a weakened currency, stubborn unemployment, and a government that was cutting back on health, education, and welfare spending in the face of significant fiscal pressures.

The Iranian new year, Nowruz, is meant to be a time of hope and renewal. But for most Iranians, there was a profound sense that the country remains stuck in a period of political and economic malaise.

How did the government manage the economy in 2023 and early 2024? What new policies did it implement?

In 2022, the Raisi administration undertook a significant and controversial subsidy reform. It eliminated the preferential exchange rate available for the importation of essential goods, making them more expensive for consumers. Authorities had aimed to roll back huge subsidies that provide Iranians with some of the cheapest petrol and diesel prices in the world. But the administration failed to continue subsidy reforms in 2023.

The effort to reduce subsidies was intended to reduce fiscal pressure on the government while freeing up resources for cash transfers to Iran’s poorest households. But such reforms are politically controversial and have led to unrest. In 2019, an overnight cut to fuel subsidies triggered protests in at least 100 cities and towns. Security forces reportedly killed at least 300 people, the deadliest unrest since the 1979 revolution at the time. Ordinary Iranians and industry groups have felt that the government is passing the buck for the country’s poor economic circumstances.

The effort to reduce subsidies was intended to reduce fiscal pressure on the government while freeing up resources for cash transfers to Iran’s poorest households. But such reforms are politically controversial and have led to unrest. In 2019, an overnight cut to fuel subsidies triggered protests in at least 100 cities and towns. Security forces reportedly killed at least 300 people, the deadliest unrest since the 1979 revolution at the time. Ordinary Iranians and industry groups have felt that the government is passing the buck for the country’s poor economic circumstances.

The Raisi administration (2021-present) had high hopes to prove itself more agile in economic policymaking than the Rouhani administration (2013-2021), which faced continual pushback from hardliners in Parliament and in Iran’s unelected bodies. But as Professor Mohammad Farzanegan has noted: “The marginalization of experts and delays in concluding negotiations with the West on saving the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the 2015 nuclear deal) have highlighted the inefficiencies of the new administration.”

Other efforts to increase economic efficiency have also faltered. In March 2022, Finance Minister Ehsan Khandouzi called for “increasing government investment” and argued that the “public sector must play a more active role in investing in physical capital.” In the op-ed, notably published in The Financial Times, Khandouzi highlighted how “negative net investment in recent years” was “severely undermining future production and household welfare.”

But little progress was made in driving new investment. The administration appeared to acknowledge this failure, declaring that it was “determined to make up for the delays in infrastructure projects.” The new budget bill, however, is simply in line with infrastructure spending in the last two budgets at around three quadrillion rials (about $491 million), meaning that government infrastructure spending will continue to fall in real terms.

Did the “resistance economy” have any successes?

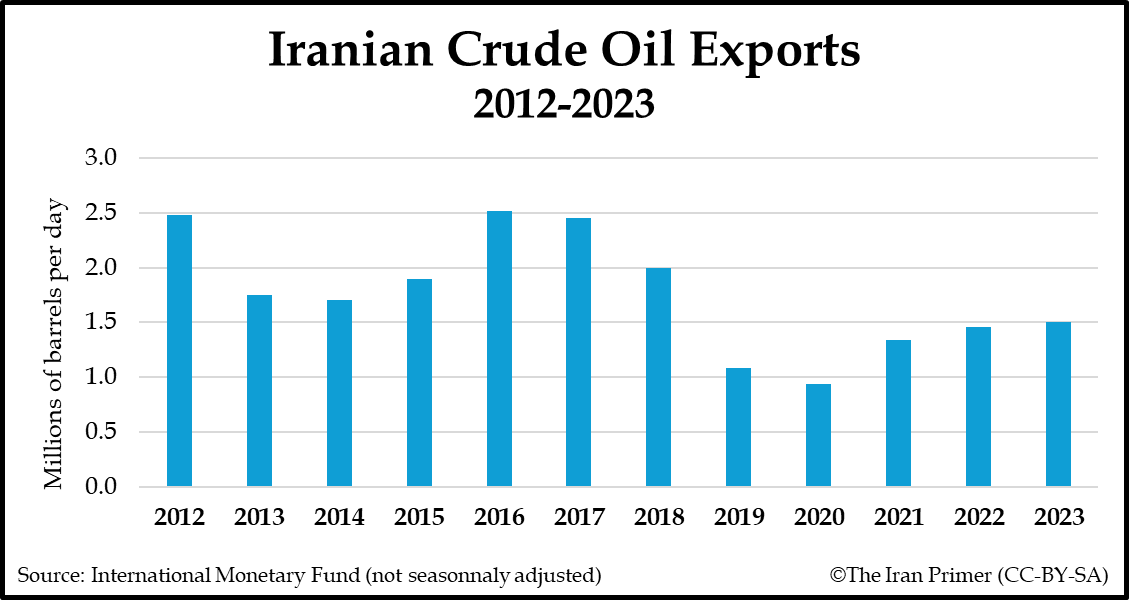

Oil exports were a bright spot for the Iranian economy. In 2023, exports rose to their highest level in five years, driven by strong demand from China, Iran’s top oil customer. Monthly exports averaged around 1.3 million barrels per day, essentially reaching a target set by oil minister Javad Owji in the previous year.

Owji has set his sights on further boosting production, which reached 3.2 million barrels per day in February 2024, an increase of around 1 million barrels per day when compared to a year earlier. He aimed “to reach 4 million barrels per day of oil production for next year,” which would mark a return to production levels during the period of JCPOA sanctions relief from 2016 to 2018. To hit this higher production target, the National Iranian Oil Company has signed $13 billion of new contracts with domestic oil producers, providing much-needed investment to increase productivity at oil and gas fields across the country.

The rebound in Iran’s oil exports has spurred accusations that the Biden administration is failing to enforce U.S. oil sanctions, possibly to keep global prices steady in an election year. Whether the rise in oil exports reflects Tehran’s success or Washington’s failure is up for debate, but whatever the reason Iran has failed to receive the full benefit for its oil exports.

Oil revenues enable Iran to import the wide range of goods that the economy needs from global markets. But the increased oil sales to China have not led to a recovery in imports from China, which suggests that a significant portion of Iran’s oil revenues remain inaccessible. Furthermore, Iran has reportedly sold oil to China at a discounted rate.

How did the economy’s performance affect the average Iranian? How did prices for everyday goods change?

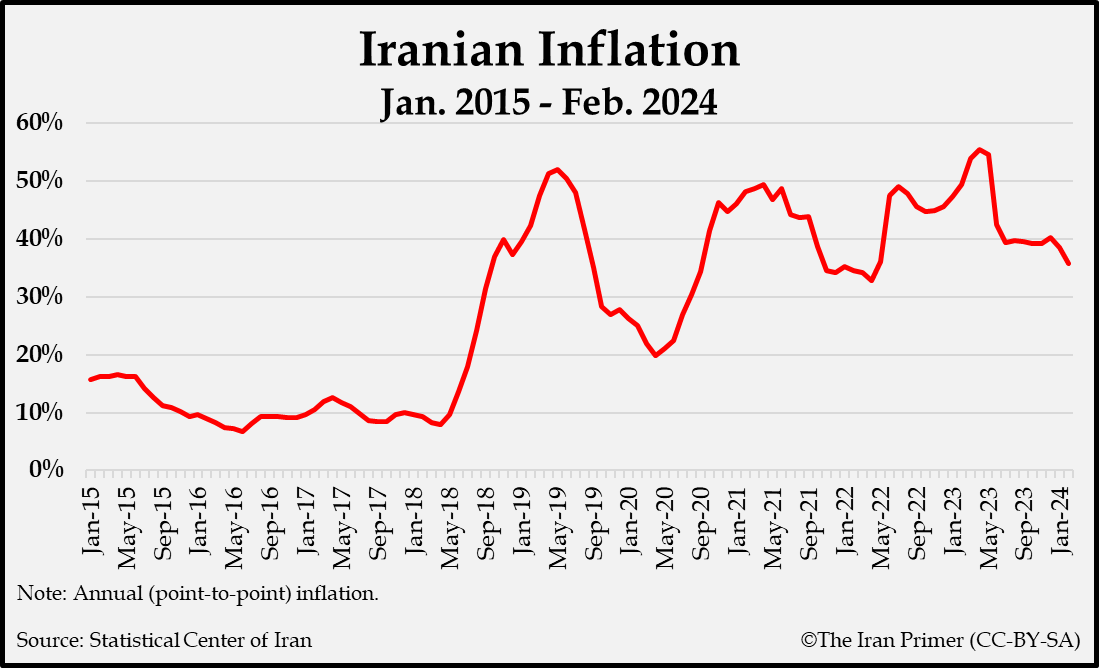

For ordinary Iranians, inflation remained the major concern. The year-on-year inflation rate has fallen significantly over the last year, easing to 35 percent in February 2024, the lowest level in two years. But that was still higher than the inflation rate of 30 percent that the Raisi administration had targeted for the calendar year ending in March 2024. Even with rising nominal incomes, Iranians have struggled to keep up with annual inflation rates above 30 percent for five years in a row. As a result, household purchasing power for many Iranians has suffered.

The stubbornly high inflation rate will add pressure on Iran’s currency, according to economist Bijan Khajepour. The free market exchange rate has already surged from 500,000 rials to the dollar at the beginning of 2024 to just over 600,000 rials to the dollar in March. The latest episode of devaluation brings an end to a six-month period during which the Central Bank of Iran had managed to keep the free market exchange rate hovering around 500,000 rials to the dollar. While the rial tends to weaken around Nowruz celebrations, due to higher demand for hard currency, the steep valuation will feed into the inflationary pressure in a vicious cycle. Such cycles of economic hardship have become as familiar to ordinary Iranians as the turning of the seasons.

Esfandyar Batmanghelidj is the founder and chief executive of the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, a think tank focused on economic diplomacy and development in the Middle East and Central Asia.