Hadi Ghaemi is the founder and executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran.

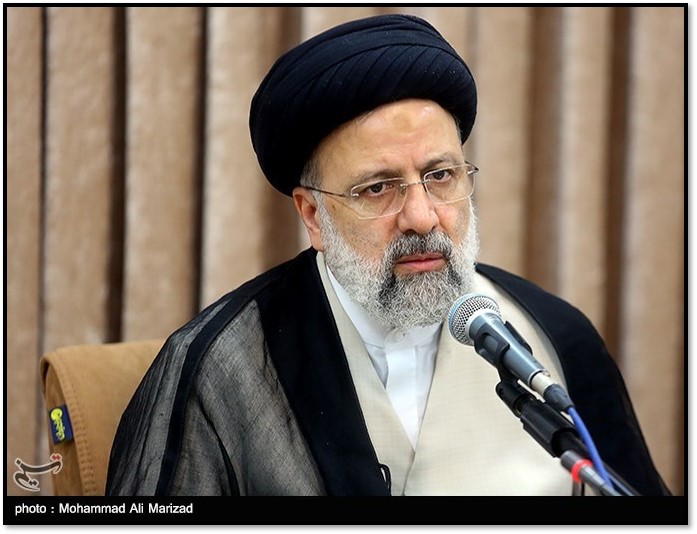

What role did Ebrahim Raisi play in the 1988 executions of thousands of Iranian political prisoners? How important or pivotal was he in the decision by the four-member commission to execute these prisoners?

The mass execution of some 5,000 captive political prisoners was widely considered an extra-judicial massacre that raised to the level of a crime against humanity. These prisoners had already been prosecuted and sentenced to prison terms. They were completing their prison terms; some had even finished their sentences and were due to be released. However, as the end of the Iran-Iraq war approached, the Iranian government at the highest levels decided that a purge of political prisoners was essential to its survival.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the supreme leader at the time, issued a brief order that any prisoner who still held to his or her political beliefs should be executed. He appointed four men, including Ebrahim Raisi, to what later became known as “the Death Committee” to organize and implement his order. At the time, Raisi was a 28-year-old prosecutor. As a member of the Death Committee, Raisi was reportedly instrumental in planning and organizing the massacre in a few months. The executions have long been considered an indication of his brutality and loyalty to the system.

What did Raisi do as a jurist or prosecutor after that? What are the best known or most notable cases associated with him?

Raisi has continuously been promoted to the most important posts in the judiciary. Shortly after the 1988 mass executions, Raisi was promoted to Prosecutor General of Tehran, a position he held until 1994. He then spent a decade, from 1994 to 2004, as the director of the National Inspection Organization, the most powerful oversight body under the judiciary. He was then appointed to be the first deputy under the chief of the judiciary from 2004 to 2014. His positions often overlapped. He was also the chief prosecutor of the Special Court for the Clergy from 2012 until 2021. From 2014 to 2016, he was Iran’s General Prosecutor while also serving, from 2015 to 2018, as head of the Astan Quds Foundation, an economically powerful religious institution. From February 2019 until his ascension to the presidency in mid-2021, he was head of the judiciary.

What position did he take on prisoners seized during the 2009 Green Movement protests?

In addition to his notorious role in the 1988 massacre, he is known as a key player in repression of the Green Movement in 2009. As the first deputy of the judiciary, he championed a campaign including the arrest, torture and execution of protestors. He is associated particularly with the fate of two political prisoners, Arash Rahmanipour and Mohammad Reza Alizamani, who were accused of participating in the Green Movement protests that started after the disputed presidential election in June 2009. However, the Rahmanipour and Alizamani were reportedly arrested as early as March 2009, which put in question how they could have participated in protests weeks or months later. Both men were executed in January 2010. Days later, Raisi claimed, “Two people who were executed and nine others who will be executed soon were definitely arrested during the recent riots.” Both men were “affiliated with one of the counter-revolutionary currents and have been involved in riots with the motive of hypocrisy and overthrow of the regime,” he said.

What was his record as chief of the Iranian judiciary between 2019 and 2021?

During his tenure as head of the judiciary, he led a campaign of repression that made the judicial system a direct instrument of the security and intelligence agencies. His last act as the head of the judiciary was a lengthy directive under the title of “Regulations for the Enforcement of the Law on the Independence of the Bar Association.” The directive stripped the Iranian Bar Association from its independence in all its matters of governance. It is considered an illegal directive, since only the Parliament can change laws regulating the governance of the Bar Association. The legal community in Iran was outraged. Other acts carried out during his short tenure as head of the judiciary included:

Executions

Executions

Iran had one of the highest per capita rates of capital punishment in the world in 2020. The death sentence was imposed on:

- Protesters and dissidents, such as Ruhollah Zam, a dissident journalist who was abducted from Iraq, taken back to Iran, and put on trial in 2020

- Non-Persian ethnic minorities, including Arab, Baluch, and Kurdish political prisoners

- Juvenile offenders

- A man accused of alcohol consumption in 2020, the first execution for this offense in two decades

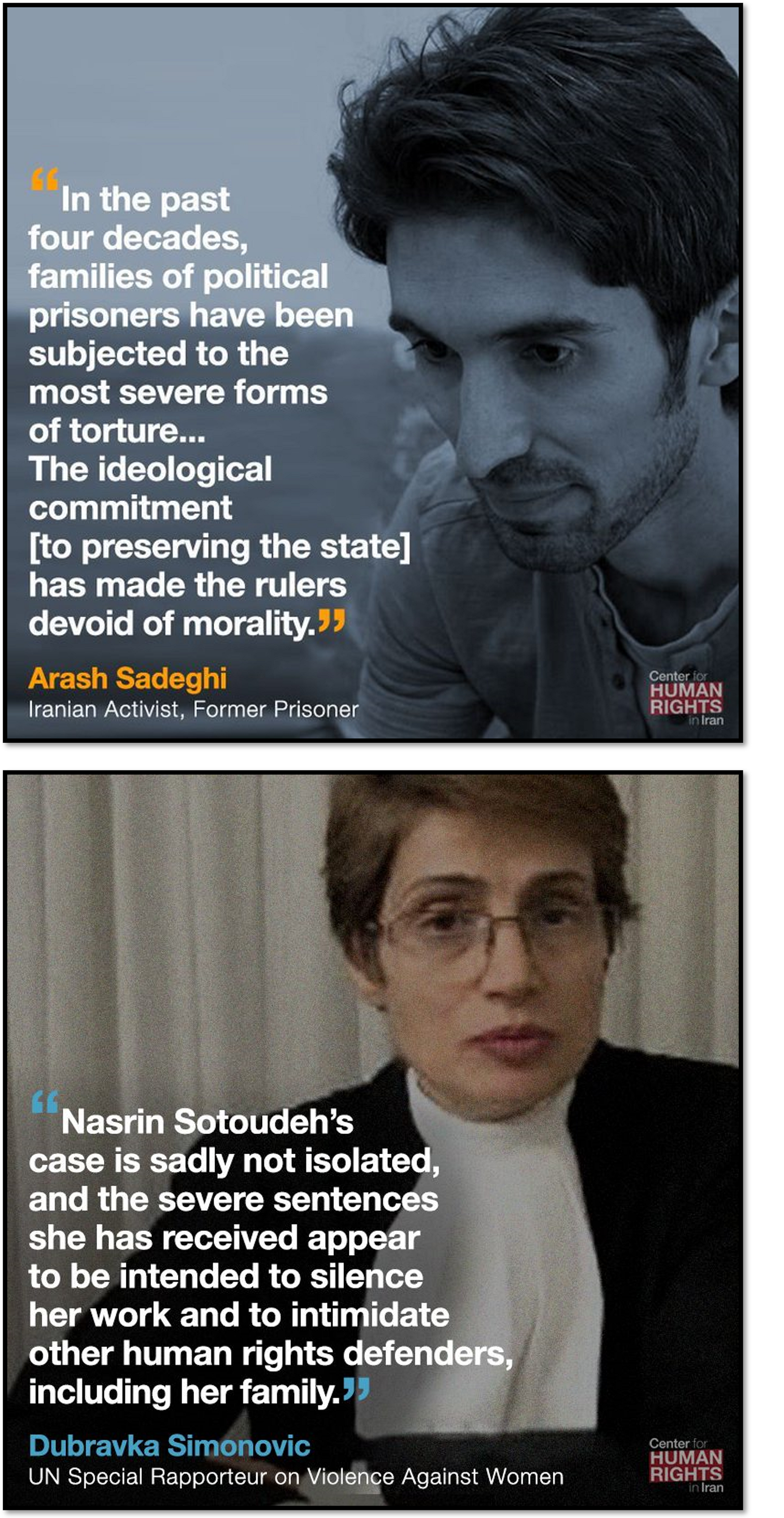

Mistreatment of political prisoners

People continued to be tried for peaceful activism. Political prisoners, particularly women, were subjected to harsher treatment that included:

- Physical and psychological torture

- Prolonged solitary confinement

- Forced confessions

- Denial of medical treatment

- Unlawful transfers to prisons far from their families

Lack of accountability

Senior officials in the security forces were not prosecuted for major incidents, including:

- The killing of at least 300 peaceful protesters and bystanders during mass street demonstrations in November 2019 with limited or no repercussions.

- The shooting down of a Ukrainian passenger plane, killing 176 people, in January 2020, even after the Revolutionary Guards accepted responsibility.

Jailing of human rights defense lawyers

Human rights-focused defense attorneys continued to be jailed and impeded from doing their jobs. Major issues included:

- At least four human rights lawyers remained imprisoned as of July 2021.

- New regulations undermined the independence of the Iranian Bar Association.

What has Raisi done on the issue of corruption, a major political issue in Iran?

During his presidential run in 2021, Raisi’s campaign centered on his record fighting corruption, including the trial of Akbar Tabari, the first deputy of former judiciary chief Sadeq Larijani. Tabari was tried in 2020 for corruption and money-laundering. Raisi's team led the prosecution and convicted Tabari, who was sentenced to 31 years in prison. The trial had overlapping political implications. It weakened Sadeq Larijani as a potential candidate to be the next supreme leader. Sadeq's brother, Ali Larijani, an influential former speaker of parliament, was also subsequently disqualified from running for president against Raisi. Three members of the Larijani family had held senior government positions since the 1980s. The highly publicized Tabari case undermined the future of two political rivals from the Larijani family who could have blocked Raisi’s path to be either president or the next supreme leader.

What is his record on the use of Islamic law versus the civil code? Is he associated more with one than the other?

In his many judicial positions over the decades, Raisi is primarily associated with the Revolutionary Courts and the Special Court for the Clergy, both of which implement the Islamic Penal Code. He does not have a record in Civil Court prosecutions.

Where did Raisi get his training in law? And what type of law? Did he study law at a seminary or at a law school? How did his judicial or legal career evolve?

According to Raisi, he studied a few years in a seminary in Mashhad, his hometown, after completing the sixth grade. At the age of 15, he enrolled in a religious seminary in Qom. He was 18 at the time of the 1979 revolution. At the age of 21, with limited educational credentials, he was appointed to be a prosecutor, simultaneously, in Karaj and Hamedan, both capitals of two major provinces. Raisi’s official resume claims that he received a master’s degree in civil law in 2001. It also claims that he entered a doctorate program in civil law at Motahari University in 2001 and received his doctorate in 2013.