Bijan DaBell

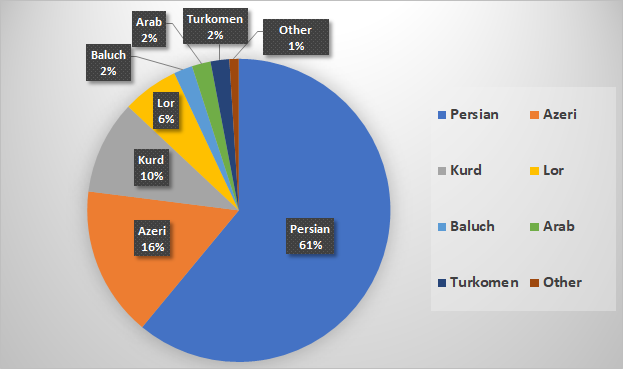

Persians are Iran’s largest ethnic group, but nearly a dozen other ethnicities represent well over a third of the 79 million population. The largest ethnic groups, which are major factors in Iranian politics, are Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchis, and Lors. Others include Turkomen, Qashqai, Mazandarani, Talysh and Gilaki. They hold dozens of seats in the current parliament. Some of the revolution’s biggest names have come from ethnic minorities:

- Mir-Hossein Mousavi—a former Prime Minister in the 1980s and a reformist presidential candidate in 2009—is an Azeri. He has been under house arrest since shortly after Green Movement protests erupted to dispute results of an election that his followers believed he had won. He comes from East Azerbaijan province.

- Mehdi Karroubi— a former speaker of parliament and another reformist presidential candidate in 2009— is a Lor. He was born in Aligoudarz in western Lorestan.

- Mohsen Rezai—former head of the Revolutionary Guards and a 2013 presidential candidate—was born in the Lor region of Khuzestan.

- Ali Khamenei— current supreme leader is reportedly half Azeri, although his official bio does not mention any Azeri heritage and says he was born in Mashhad.

- Sadeq Mahsouli—former minister of interior from 2008-2009 and minister of social security from 2009 to 2011—is also Azeri. He was born in the Azeri city of Urmia.

- Rahim Safavi—former commander of the Revolutionary Guards from 1997 to 2007, is an ethnic Azeri.

Yet ethnic minorities are a sensitive political issue, which is one reason accurate numbers in politics and the military are not easily available. The Islamic Republic prefers to emphasize religion to foster national identity and avoid problems of ethnic divisions. Many politicians do not discuss their ethnicity, although several Azeri, Kurdish, Baluchi, and Arab groups have expressed frustration with Tehran. Some have openly protested over several issues, including:

- Lack of government spending on development in provinces with large ethnic minorities,

- Revenues from oil and natural resources in their regions being spent on other cities and provinces,

- Greater regional autonomy,

- And limits on use of their traditional languages.

Source: CIA World Factbook (2016)

Two articles of Iran’s constitution cover the status of ethnic minorities:

Chapter 2, Article 15: The official language and script of Iran, the lingua franca of its people, is Persian. Official documents, correspondence, and texts, as well as text-books, must be in this language and script. However, the use of regional and tribal languages in the press and mass media, as well as for teaching of their literature in schools, is allowed in addition to Persian.

Chapter 3, Article 19: All people of Iran, whatever the ethnic group or tribe to which they belong, enjoy equal rights; and color, race, language, and the like, do not bestow any privilege.

Ethnic rights occasionally come up in elections. In his successful bid for the presidency in 2013, Hassan Rouhani promised to allow ethnic and religious minorities to be involved “in all political and administrative levels of government, including membership in the cabinet.” He also pledged to allow the “teaching of Iranian native languages” such as Kurdish, Azeri, and Arabic. And he met with Arab tribal sheikhs from Ahwaz during the campaign. The election results reflected a strong showing in provinces with significant minorities. The map below highlights areas where minorities are concentrated.

Source: CIA (2004)

Generally, however, the integration of ethnic minorities into Iran’s Persian-centric society has varied since the 1979 revolution. Activists have faced arrest, prolonged detention, and physical abuse, according to the U.S. State Department. Non-Persian languages have been restricted in schools. Iran’s ethnic minorities are less interested in secession and more interested in increasing their rights as Iranian citizens. Some have proposed that Iran become a federation that allows ethnic autonomy in governing their own affairs. The following is a rundown of the five largest minorities, their activism, and their political influence.

Azeris

Azeris are Iran’s largest ethnic minority, numbering at least 12 million. But according to some estimates, up to 20 million live in Iran—almost one-quarter of the population. Most Azeris are well integrated into Iranian society, although their traditional language is closer to Turkish than Persian. Most are Shiite Muslims and are afforded more freedoms in the Shiite-dominated Islamic Republic than non-Shiite ethnic minorities.

But Azeris have faced political and cultural discrimination. The U.S. State Department reported that the government prohibited Azeris from speaking their language in schools, harassed Azeri activists, and changed Azeri town names.

Azeris share the same ethnic background with the majority population in neighboring Azerbaijan. These groups were divided in 1828 by the Treaty of Turkmanchai, which gave the northern portion of Azerbaijan to Russia and southern portion to Iran. Azeri involvement in Iran’s government was greatly reduced by the rise of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925. The Islamic Republic continued to suppress the Azeri population, notably during a brutal 1981 crackdown against an Azeri uprising in Tabriz.

Yet Azeris have played a larger role in the Iranian military and politics than other ethnic minorities. Yahya Rahim Safavi (left) was commander of the Revolutionary Guards—one of the most important military positions in Iran—from 1997 to 2007. Mir-Hossein Mousavi, who was prime minister in the 1980s and a reformist presidential candidate in 2009, is Azeri. Sadeq Mahsouli, former minister of interior from 2008 to 2009 and minister of social security from 2009 to 2011, is also an Azeri.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is also believed to be an ethnic Azeri. His grandfather was born in the Azeri village of Khamane, but was raised in Najaf, Iraq. Khamenei’s official website makes no mention of an Azeri heritage.

Azeri nationalism has grown over the last two decades, although most Iranian Azeris are not openly in favor of separation from Iran. Nationalist publications aimed at Iranian Azeris have been on the rise. Many also have access to Turkish satellite television, so their knowledge of Turkey and Azerbaijan has increased. In 1996, Mahmudali Chohraganli—an Azeri nationalist leader—was elected to represent Tabriz in the Iranian parliament. The government did not allow him to take his seat in the parliament and detained him.

In May 2006, large-scale protests erupted in Tehran and northwestern Iran after a state-run newspaper published a cartoon depicting an Azeri as a cockroach. The newspaper was shut down, and the cartoonist and editor were jailed. The Supreme Leader blamed the protests on the West. “Azeris have always bravely defended the Islamic revolution and the sovereignty of this country,” he said.

Azeris mostly live in northwestern Iran, notably in the provinces of

East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan,

Ardabil, and Zanjan. About one-third of Tehran’s population is also reportedly Azeri. Smaller numbers reside in Hamadan, Qazvin and Karaj.

Kurds

Iranian Kurds total nearly 8 million, representing around 10 percent of Iran’s population. Kurds reportedly have 18 members in Iran’s 290-seat parliament, according to the Kurdistan Tribune.

After the 1979 revolution, Iran’s Kurds launched a failed separatist movement to break away from the Islamic Republic. They shifted in recent years to non-violent tactics, although occasional clashes with Iranian security forces continue. Persecution of Kurds who protest government policies has increased since 2000, particularly under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, according to the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center.

After the disputed 2009 presidential elections, Iranian security forces targeted Kurdish activists. The U.S. State Department reported that more than two dozen Kurds were sentenced to death in 2012 for political and security-related crimes. Kurdish newspapers are also banned in Iran.

Kurdish groups in the neighboring countries of Iraq, Syria, and Turkey have fought their governments to establish various levels of autonomy. But Kurdish groups in Iran have not reached a consensus for demanding autonomy. Many Kurds prefer to work within Iran’s current political system in order to strengthen their rights as citizens. An Iranian Kurd dressed in traditional clothing is pictured above.

Iranian Kurds also have mixed opinions about the new president. In the 2013 election, Hassan Rouhani promised to improve the status of minority groups, which made him popular among some Kurdish voters and activists. The president of United Kurds in Iran, a political group, urged Kurds to vote in the June 2013 presidential election. Kurdish Member of Parliament Salar Muradi also said, “This election is an opportunity to get Kurdish rights and, if any candidate has solution to Kurdish issues, we will support them.”

But other Kurdish leaders remained unsure about Rouhani’s proposed reforms, and some Kurdish groups boycotted the election. Following the election, Khalid Azizi, secretary general of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran, a political group, said the election would not change things for Iranians. “These elections aren’t about human rights or the rights of the Iranian people,” he said. “It is a way for the Iranian regime to come out of its own crisis. People participate only to find a solution for the economic crisis the regime has got them into.”

Iranian authorities in Tehran recently announced plans to establish a new security force in Iran’s western provinces that would recruit local Kurds. But some Kurdish groups said the new force was only part of a plan to exert greater control over the Kurdish regions. The Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran questioned Tehran’s intentions since Kurdish groups have not engaged in unrest.

Most Iranian Kurds reside in the mountainous areas bordering Turkey and Iraq, mainly in the provinces of Kurdistan and Kermanshah. West Azerbaijan, Hamadan, Ilam, Northern Khorasan, and Lorestan also have Kurdish communities. The majority practice Sunni Islam, although some are Shiites, Sufi, or Jewish.

Baluchis

Baluchis number between 1.5 million and 2 million in Iran. They are part of a wider regional population of about 10 million spread across Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Baluchis are largely Sunni Muslims, which has contributed to tension with Iran’s Shiite government. Baluchis are noticeably underrepresented in government positions. Yet the local government in the Baluchistan province is largely made up of Shiite Persians, and the region has many Shiite missionaries.

Jundallah (Soldiers of God)—a Baluchi militant group—was established in 2003 to fight for Sunni Baluchi rights. Jundallah has reportedly organized suicide bombings and small scale attacks. In March 2006, Jundallah ambushed a government convoy, kidnapped eight soldiers, and executed a Revolutionary Guard. It also allegedly kidnapped an Iranian nuclear scientist in September 2010. Jundallah is part of a larger separatist conflict playing out in Baluchi inhabited areas of neighboring Pakistan.

The Iranian government has also cracked down on Baluchi journalists, and human rights activists have faced arbitrary arrest, physical abuse, and unfair trials, according to the U.S. State Department. Three political prisoners were tortured and forced to make confessions on television before being executed in 2012.

Baluchistan is significant to the Iranian government since the region borders Pakistan and is rife with drug smuggling, although the government has struggled to control the area. The Baluchis live in Iran’s arid southeast, which is a poorly developed area with limited access to education, employment, health care, and housing, according to the United Nations. Around ten percent of Baluchis are nomadic or semi-nomadic. The rest live in towns or on farms.

Arabs

Arabs make up two percent of Iran’s total population and number more than 1.5 million. They have faced increased oppression and discrimination in recent years, according to the U.S. State Department. Since 2005, international human rights organizations have reported arrests of protesters over discrimination or calls to boycott elections. Arabs from the town of Ahwaz in the Khuzestan province (left) have faced discrimination in education employment, politics, and culture, the human rights groups claimed.

Arabs make up two percent of Iran’s total population and number more than 1.5 million. They have faced increased oppression and discrimination in recent years, according to the U.S. State Department. Since 2005, international human rights organizations have reported arrests of protesters over discrimination or calls to boycott elections. Arabs from the town of Ahwaz in the Khuzestan province (left) have faced discrimination in education employment, politics, and culture, the human rights groups claimed.

The member of parliament from Abadan, Mohammad Saeed Ansari, has repeatedly complained about high unemployment in the province of Khuzestan, despite the region’s significant oil reserves and its agricultural, ship-building, manufacturing, and petrochemical industries. Only half of those employed by these companies are local Arabs, he said, and less than five percent of the workers in Abadan are actually from the province. Ansari claims that racism towards Arabs has also denied them opportunities to work in local government.

In August 2013, an elderly Arab from Ahwaz publicly confronted President Rouhani with accusations that the government systematically ignored Arab demands for jobs, education, clean water, and human rights. Rouhani remained silent and the man was interrupted by a presidential aid.

Former Defense Minister Ali Shamkhani—the only Arab to have served in any government cabinet—criticized the regime for its poor treatment of Arabs. He accused it especially for failing to develop the Ahwaz area, which was badly hit during Iran’s eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s. Shamkhani called on the government to fight discrimination and poverty, which he warned was spurring disloyalty among Arabs.

Arabs reside mainly along the border with Iraq in Iran’s southwestern Khuzestan province. Most are Shiite Muslims. A minority are Sunni, and smaller numbers are Christian and Arabic-speaking Jews. Iranian Arabs fought on the Iranian side during the Iran-Iraq war.

Lors

The Lors are an ethnic group numbering around 4.8 million. They are a mix of Persian and Arab descent. Mehdi Karroubi, a former speaker of parliament and a presidential candidate in 2009, is a Lor. He was born in Aligoudarz in western Lorestan. Mohsen Rezai (left), former head of the Revolutionary Guards and a presidential candidate in 2013, is a Lor from Khuzestan.

Lors have been less vocal than other ethnic minorities about their plight. But in August 2013, a Lor member of parliament, Mohammad Bozorgvari, reportedly said that unless President Hassan Rouhani’s ministerial nominees paid special attention to his region, he would beat them up with sticks. A representative of Lorestan’s writers union, Ali Sarmian, called Bozorgvari’s remark “irresponsible.” More than a dozen Lors reportedly protested the comment outside parliament.

The majority of Lors are Shiite Muslims. They mainly reside in the mountainous along the western border with Iraq. Most Lors live in the provinces of Lorestan, Bakhtiari, Kohgiluyeh, and Boyer-Ahmed. Smaller numbers live in Khuzestan, Fars, Ilam, Hamadan, and Bushehr. They speak Lori, an oral language that is similar to Persian.

Photo credits:

Mir Hossein Mousavi and Medhi Karroubi via Facebook

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org

Yet Azeris have played a larger role in the Iranian military and politics than other ethnic minorities. Yahya Rahim Safavi (left) was commander of the Revolutionary Guards—one of the most important military positions in Iran—from 1997 to 2007. Mir-Hossein Mousavi, who was prime minister in the 1980s and a reformist presidential candidate in 2009, is Azeri. Sadeq Mahsouli, former minister of interior from 2008 to 2009 and minister of social security from 2009 to 2011, is also an Azeri.

Yet Azeris have played a larger role in the Iranian military and politics than other ethnic minorities. Yahya Rahim Safavi (left) was commander of the Revolutionary Guards—one of the most important military positions in Iran—from 1997 to 2007. Mir-Hossein Mousavi, who was prime minister in the 1980s and a reformist presidential candidate in 2009, is Azeri. Sadeq Mahsouli, former minister of interior from 2008 to 2009 and minister of social security from 2009 to 2011, is also an Azeri.

Baluchis number between 1.5 million and 2 million in Iran. They are part of a wider regional population of about 10 million spread across Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Baluchis are largely Sunni Muslims, which has contributed to tension with Iran’s Shiite government. Baluchis are noticeably underrepresented in government positions. Yet the local government in the Baluchistan province is largely made up of Shiite Persians, and the region has many Shiite missionaries.

Baluchis number between 1.5 million and 2 million in Iran. They are part of a wider regional population of about 10 million spread across Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Baluchis are largely Sunni Muslims, which has contributed to tension with Iran’s Shiite government. Baluchis are noticeably underrepresented in government positions. Yet the local government in the Baluchistan province is largely made up of Shiite Persians, and the region has many Shiite missionaries. Arabs make up two percent of Iran’s total population and number more than 1.5 million. They have faced increased oppression and discrimination in recent years, according to the U.S. State Department. Since 2005, international human rights organizations have reported arrests of protesters over discrimination or calls to boycott elections. Arabs from the town of Ahwaz in the Khuzestan province (left) have faced discrimination in education employment, politics, and culture, the human rights groups claimed.

Arabs make up two percent of Iran’s total population and number more than 1.5 million. They have faced increased oppression and discrimination in recent years, according to the U.S. State Department. Since 2005, international human rights organizations have reported arrests of protesters over discrimination or calls to boycott elections. Arabs from the town of Ahwaz in the Khuzestan province (left) have faced discrimination in education employment, politics, and culture, the human rights groups claimed.