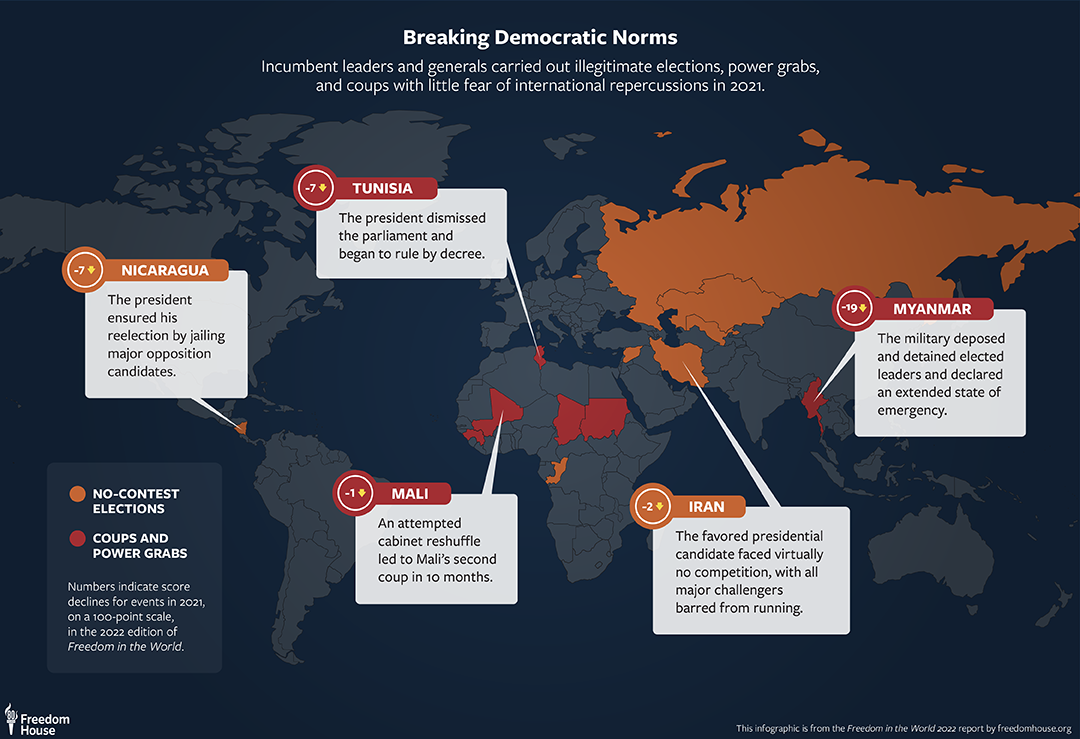

In Freedom House’s annual report, Iran received a score of 14 out of 100, with 100 being the most free. It also received poor marks for political rights and civil liberties. Iran’s score declined slightly from 16 in the previous year in part due to “unusually heavy regime manipulation” in the 2021 presidential election.

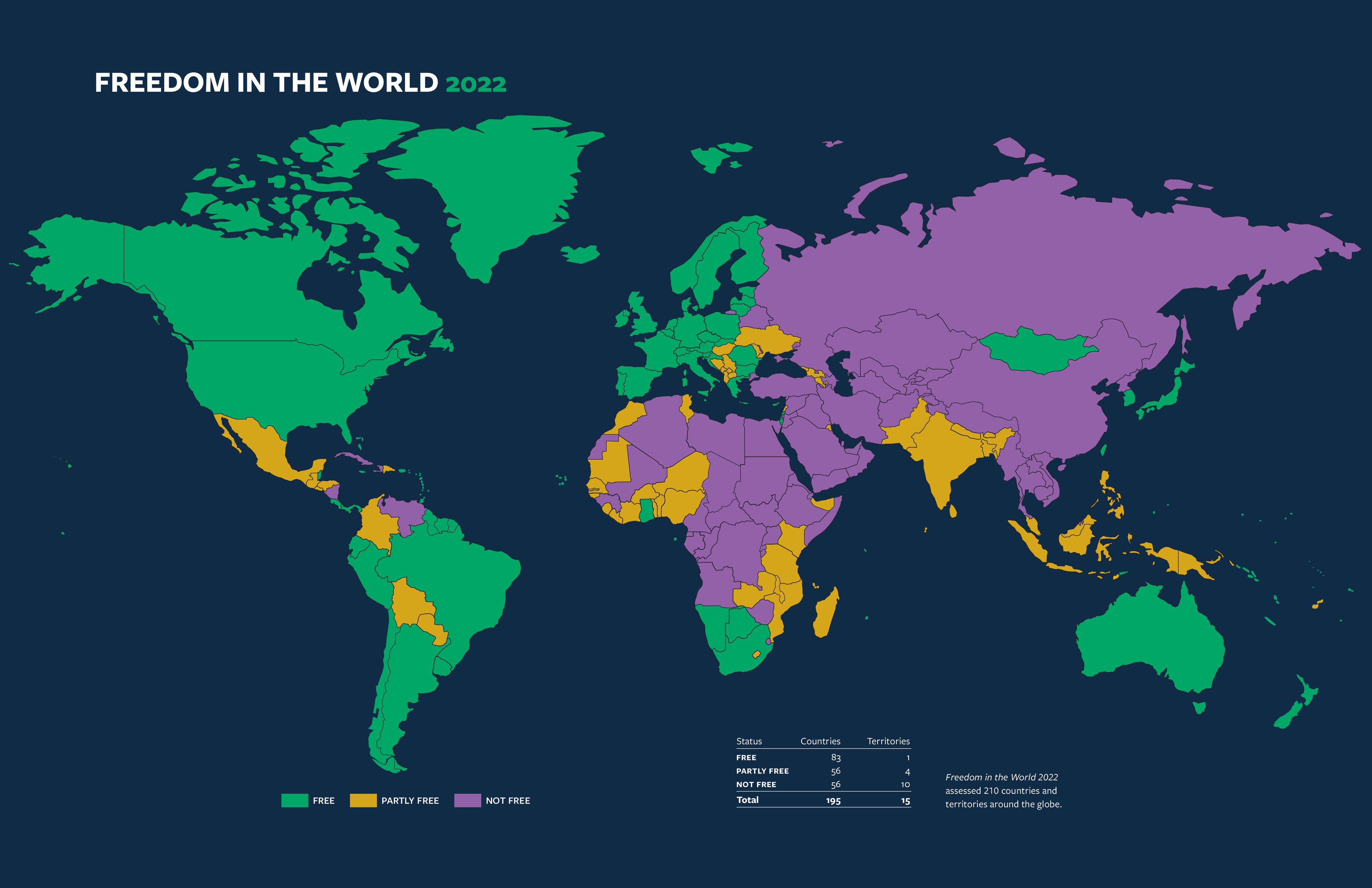

“Freedom in the World 2022” is the organization’s flagship report, which assesses the condition of political rights and civil liberties around the world. It is composed of numerical ratings and supporting descriptive texts for 210 countries and territories. The following is Iran’s profile from the report.

Green = Free, Yellow = Partly Free, Purple = Not Free

Iran

Freedom in the World Scores

Aggregate Score: 14/100

(0=Least Free, 100=Most Free)

Political Rights: 4/40

Civil Liberties: 10/60

Overview

The Islamic Republic of Iran holds elections regularly, but they fall short of democratic standards due in part to the influence of the hard-line Guardian Council, an unelected body that disqualifies all candidates it deems insufficiently loyal to the clerical establishment. Ultimate power rests in the hands of the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and the unelected institutions under his control. These institutions, including the security forces and the judiciary, play a major role in the suppression of dissent and other restrictions on civil liberties.

Key Developments in 2021

- Judicial chief Ebrahim Raisi was elected president in June, winning 62 percent of the vote in a contest marred by the disqualification or withdrawal of major challengers and official pressure on the media to refrain from critical reporting. Turnout stood at 48.8 percent, the lowest for a presidential poll in the Islamic Republic’s history.

- In July, the parliament began considering a bill that would criminalize the use and distribution of virtual private networks (VPNs) and require internet users to provide their legal identities to access online services, among other measures. The bill remained under consideration but was not passed by year’s end.

- Demonstrators rallied to protest water shortages and poor living conditions in several provinces in the second half of July, with activity centered in the southern province of Khuzestan. Authorities used lethal force to disperse the protests, causing at least 11 deaths.

- In November, the Guardian Council ratified a law restricting access to abortion and banning the distribution of free contraceptives. The new law can be used on an “experimental” basis for seven years.

Political Rights

A. Electoral Process

A1 (0/4 points) Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections?

The supreme leader, who has no fixed term, is the highest authority in the country. He is the commander in chief of the armed forces and appoints the head of the judiciary, the heads of state broadcast media, and the Expediency Council—a body tasked with mediating disputes between the Guardian Council and the parliament. He also appoints six members of the Guardian Council; the other six are jurists nominated by the head of the judiciary and confirmed by the parliament, all for six-year terms. The supreme leader is appointed by the Assembly of Experts, which monitors his work. However, in practice his decisions appear to go unchallenged by the assembly, whose proceedings are kept confidential. The current supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, succeeded Islamic Republic founder Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989.

The president, the second-highest-ranking official in the Islamic Republic, appoints a cabinet that must be confirmed by the parliament. He is elected by popular vote for up to two consecutive four-year terms. Judicial head Ebrahim Raisi won the presidency in June 2021 with 62 percent of the vote, in a contest marred by manipulation on the part of the establishment. The Guardian Council rejected most of the nearly 600 aspiring candidates—including 40 women—in May 2021, approving only 7 applicants. Among those rejected were outgoing first vice president Eshaq Jahangiri, a reformist, and former parliament speaker Ali Larijani, a conservative. Three approved candidates dropped out several days before the poll.

The contest was also affected by official pressure on the media, with journalists told to refrain from issuing reports criticizing the poll or Raisi. Turnout was the lowest in a presidential election in the Islamic Republic’s history, at 48.8 percent.

Score Change: The score declined from 1 to 0 because the June presidential election featured unusually heavy regime manipulation to ensure the victory of President Raisi, including pressure on the media and the disqualification or withdrawal of all major challengers, which resulted in a lack of competition and record-low voter turnout.

A2 (1/4 points) Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections?

Members of the 290-seat parliament are elected to four-year terms. Elections for the body were held in February 2020, with most seats going to hard-liners and conservatives loyal to the supreme leader. Ahead of the vote, the Guardian Council disqualified more than 9,000 of the 16,000 people who had registered to run, including large numbers of reformist and moderate candidates. Voter turnout, the lowest for parliamentary elections in the history of the Islamic Republic at 42.6 percent, was likely depressed by factors including the mass disqualifications and the announcement of the first coronavirus cases just two days before the balloting. The outbreak was believed to have begun weeks earlier, raising suspicions that the authorities delayed disclosing it for political reasons; Khamenei denounced foreign “propaganda” for supposedly exaggerating the health threat to frighten voters.

Elections for the Assembly of Experts, a group of 86 clerics chosen by popular vote to serve eight-year terms, were last held in 2016. Only 20 percent of the would-be candidates were approved to run, a record low. A majority of the new assembly ultimately chose hard-line cleric Ahmad Jannati, head of the Guardian Council, as the body’s chairman. Jannati was reelected to the Assembly of Experts’ chairmanship in February 2021.

A3 (1/4 points) Are the electoral laws and framework fair, and are they implemented impartially by the relevant election management bodies?

The electoral system in Iran does not meet international democratic standards. The Guardian Council, controlled by hard-line conservatives and ultimately by the supreme leader, vets all candidates for the parliament, the presidency, and the Assembly of Experts. The council typically rejects candidates who are not considered insiders or deemed fully loyal to the clerical establishment, as well as women seeking to run in the presidential election. As a result, Iranian voters are given a limited choice of candidates.

B. Political Pluralism and Participation

B1 (0/4 points) Do the people have the right to organize in different political parties or other competitive political groupings of their choice, and is the system free of undue obstacles to the rise and fall of these competing parties or groupings?

Only political parties and factions loyal to the establishment and to the state ideology are permitted to operate. Reformist groups have come under increased state repression, especially since 2009, and affiliated politicians are subject to arbitrary detention and imprisonment on vague criminal charges.

B2 (1/4 points) Is there a realistic opportunity for the opposition to increase its support or gain power through elections?

While some space for shifts in power between approved factions within the establishment has existed in the past, the unelected components of the constitutional system represent a permanent barrier to opposition electoral victories and genuine rotations of power. In May 2021, for example, then outgoing first vice president Jahangiri, who is considered a reformist, was disqualified from running for president.

Top opposition leaders face restrictions on their movement. Mir Hossein Mousavi, Zahra Rahnavard, and Mehdi Karroubi—leaders of the reformist Green Movement, whose protests were violently suppressed following the disputed 2009 presidential election—have been under house arrest without formal charges since 2011. Restrictions on Mousavi and Karroubi have sometimes been loosened in recent years, however; Mousavi and Karroubi were allowed to meet relatives in 2017, while Karroubi made a public speech in October 2021. Reformist former president Mohammad Khatami is the subject of a media ban that prohibits the press from mentioning him and publishing his photos. Former hard-line president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who fell out of favor for challenging Khamenei, was barred from running in the 2017 and 2021 presidential elections.

B3 (0/4 points) Are the people’s political choices free from domination by forces that are external to the political sphere, or by political forces that employ extrapolitical means?

The choices of both voters and politicians are heavily influenced and ultimately circumscribed by Iran’s unelected state institutions and ruling clerical establishment.

B4 (/1/4 points) Do various segments of the population (including ethnic, racial, religious, gender, LGBT+, and other relevant groups) have full political rights and electoral opportunities?

Men from the Shiite Muslim majority population dominate the political system. Women remain significantly underrepresented in politics and government. While President Raisi appointed Ensieh Khazali as vice president for women and family affairs in September 2021, he nominated no women to serve in the cabinet the month before. No women candidates have ever been allowed to run for president.

Five seats in the parliament are reserved for recognized non-Muslim minority groups: Jews, Armenian Christians, Assyrian and Chaldean Christians, and Zoroastrians. However, members of non-Persian ethnic minorities and especially non-Shiite religious minorities are rarely awarded senior government posts, and their political representation remains weak.

Functioning of Government

C1 (0/4 points) Do the freely elected head of government and national legislative representatives determine the policies of the government?

The elected president’s powers are limited by the supreme leader and other unelected authorities. The June 2021 presidential election was tightly controlled by the regime, further reducing the democratic legitimacy of the executive.

The powers of the elected parliament are similarly restricted by the supreme leader and the unelected Guardian Council, which must approve all bills before they can become law. The council often rejects bills it deems un-Islamic. Nevertheless, the parliament has been a platform for heated political debate and criticism of the government, and legislators have frequently challenged presidents and their policies.

Score Change: The score declined from 1 to 0 because the tightly controlled June presidential election further reduced the democratic legitimacy of the executive branch and demonstrated the dominance of the state’s unelected institutions.

C2 (0/4 points) Are safeguards against official corruption strong and effective?

Corruption remains endemic at all levels of the bureaucracy, despite regular calls by authorities to tackle the problem. Powerful actors involved in the economy, including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and bonyads (endowed foundations), are above scrutiny in practice, and restrictions on the media and civil society activists prevent them from serving as independent watchdogs to ensure transparency and accountability.

The judiciary launched an anticorruption crackdown in 2019, which subsequently triggered high-profile prosecutions of former politicians and court officials. Raisi also made corruption a major theme of his 2017 and 2021 presidential campaigns. However, authorities have resisted recent scrutiny on official corruption; in July 2021, four journalists working for state-run news sites received false news and defamation convictions for reporting on suspected corruption within the Oil Ministry but reportedly received no prison terms.

C3 (0/4 points) Does the government operate with openness and transparency?

The transparency of Iran’s governing system is extremely limited in practice, and powerful elements of the state and society are not accountable to the public. A 2009 access to information law, for which implementing regulations were finally adopted in 2015, grants broadly worded exemptions allowing the protection of information whose disclosure would conflict with state interests, cause financial loss, or harm public security, among other stipulations.

The ruling establishment has actively suppressed or manipulated information on important topics. For example, the IRGC initially denied involvement in the destruction of a Ukrainian passenger jet in January 2020. Several days after the incident, it admitted its personnel mistook the plane for a missile and shot it down.

The government also engaged in censorship to conceal the extent of the COVID-19 outbreak when it was detected in 2020, reportedly telling journalists to rely only on official statistics and warning health-care workers not to discuss infections or deaths with the media. Officials are known to promote COVID-19-related disinformation; in January 2021, Supreme Leader Khamenei called US– and UK-produced vaccines “completely untrustworthy,” banning their use in Iran.

Civil Liberties

Freedom of Expression and Belief

D1 (0/4 points) Are there free and independent media?

Media freedom is severely limited both online and offline. The state broadcasting company is tightly controlled by hard-liners and influenced by the security apparatus. News and analysis are heavily censored, while critics and opposition members are rarely, if ever, given a platform on state-controlled television, which remains a major source of information for many Iranians. State television has a record of airing confessions extracted from political prisoners under duress, and it routinely carries reports aimed at discrediting dissidents and opposition activists.

Newspapers and magazines face censorship and warnings from authorities about which topics to cover and how. Tens of thousands of foreign-based websites are filtered, including news sites and major social media services. Satellite dishes are banned, and Persian-language broadcasts from outside the country are regularly jammed. Police periodically raid private homes and confiscate satellite dishes. Iranian authorities have pressured journalists working for Persian-language media outside the country by summoning and threatening their families in Iran.

Iranian authorities placed significant pressure on journalists ahead of the June 2021 presidential election. That month, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) noted that journalists received at least 42 summonses or threats from prosecutors and intelligence agencies after the candidate-registration period ended in May. RSF also reported that foreign journalists were assigned government minders.

Several journalists were detained or imprisoned during 2021. In August, two journalists in western Iran received sentences of two-and-a-half-years’ imprisonment and 90 lashes over false-news accusations; their sentences still required the approval of an appeals court as of that month. Also in August, photojournalist Majid Saeedi was arrested after photographing camps housing Afghan refugees, though no charges were immediately disclosed. In September, financial reporter Amir-Abbas Azarmvand was arrested by intelligence officers on propaganda charges. In November, Manoochehr Aghaei, a reporter for a state-run news site and operator of an independent social media outlet, began an eight-month prison term for “spreading propaganda against the system.”

In November 2021, the Culture Ministry’s Press Supervisory Board revoked the license of state-run daily newspaper Kelid after it used a photograph of Supreme Leader Khamenei in an article on poverty.

The Islamic Republic has been known to target Iranian journalists operating abroad; in July 2021, US prosecutors alleged that four Iranians intended to kidnap journalist Masih Alinejad, who fled Iran in 2009, and return her to the country.

D2 (0/4 points) Are individuals free to practice and express their religious faith or nonbelief in public and private?

Iran is home to a majority Shiite Muslim population and Sunni Muslim, Baha’i, Christian, and Zoroastrian minorities. The constitution recognizes only Zoroastrians, Jews, and certain Christian communities as non-Muslim religious minorities, and these small groups are relatively free to worship. The regime cracks down on Muslims who are deemed to be at variance with the state ideology and interpretation of Islam.

Sunni Muslims complain that they have been prevented from building mosques in major cities and face difficulty obtaining government jobs. In recent years, there has been increased pressure on the Sufi Muslim order Nematollahi Gonabadi, including destruction of its places of worship and the jailing of some of its members.

The government also subjects some non-Muslim minorities to repressive policies and discrimination, including Baha’is and unrecognized Christian groups. Baha’is are systematically persecuted, sentenced to prison, and banned from access to higher education. In May 2021, the Baha’i International Community reported on multiple raids of Baha’i homes, along with the detention of more than 20 people. Later that month, the Revolutionary Court of Borazjan issued prison sentences against six Baha’i; one defendant received an 11-year sentence for “propaganda activities against the regime” for discussing their faith, while the other five received 12-and-a-half-year sentences for “assisting in propaganda activities.”

D3 (1/4 points) Is there academic freedom, and is the educational system free from extensive political indoctrination?

Academic freedom remains limited in Iran, and universities have experienced harsh repression since 2009. Khamenei has warned that universities should not be turned into centers for political activities. Students have been prevented from continuing their studies for political reasons or because they belong to the Baha’i community. Foreign scholars visiting Iran are vulnerable to detention on trumped-up charges.

In February 2021, Shahid Beheshti University professor Reza Eslami, a dual Iranian Canadian national, was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment for cooperating with an enemy state after he participated in a training course funded by a US-based nongovernmental organization (NGO). In October, the Court of Appeals in Tehran issued a modified five-year sentence against Eslami.

D4 (1/4 points) Are individuals free to express their personal views on political or other sensitive topics without fear of surveillance or retribution?

Iran’s vaguely defined restrictions on speech, harsh criminal penalties, and state monitoring of online communications are among several factors that deter citizens from engaging in open and free private discussion. Despite the risks and limitations, many do express dissent on social media, in some cases circumventing official blocks on certain platforms.

In July 2021, the parliament began considering a bill that would impose wide-ranging restrictions on Iranian internet users. The bill would criminalize the use and distribution of VPNs, while users would be required to provide their legal identification to access online services. The bill would also require the operators of foreign social networks and other services to open offices within the Islamic Republic. The bill remained under consideration as of October 2021 and is expected to achieve ratification in 2022.

Associational and Organizational Rights

E1 (0/4 points) Is there freedom of assembly?

The constitution states that public demonstrations may be held if they are not “detrimental to the fundamental principles of Islam.” In practice, only state-sanctioned demonstrations are typically permitted, while other gatherings have in recent years been forcibly dispersed by security personnel, who detain participants.

Authorities responded forcefully to several protests during 2021. Demonstrators in several provinces, including Khuzestan, held rallies over water shortages and poor living conditions beginning in mid-July. Security forces responded by detaining participants and using lethal force as the month progressed. In early August, Amnesty International reported at least 11 deaths at the hands of security forces during the previous month’s protests.

Authorities also used force to disperse a peaceful protest in the city of Naqadeh in early August 2021. Amnesty International reported one death and several dozen injuries in that incident.

Protests over water shortages were held in Isfahan Province beginning in early November 2021. Authorities initially tolerated the protests before launching a crackdown later in the month, using tear gas and guns loaded with shrapnel and arresting 67 people.

E2 (0/4 points) Is there freedom for nongovernmental organizations, particularly those that are engaged in human rights– and governance-related work?

NGOs that seek to address human rights violations are generally suppressed by the state. For example, the Center for Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) remains closed, with several of its members imprisoned. In May 2021, CHRD vice president Narges Mohammadi was sentenced to two-and-a-half years’ imprisonment and 80 lashes by the Tehran Criminal Court in absentia. Mohammadi was taken into custody by intelligence agents in November, after which she was sent to Tehran’s Evin prison to serve her sentence.

Groups that focus on apolitical issues also face crackdowns. In March 2021, a court ordered the dissolution of the Imam Ali Popular Students Relief Society, a prominent NGO that supported the poor and natural disaster survivors. In its ruling, the court sustained an Interior Ministry assertion that the NGO had deviated from its mission and “questioned Islamic rulings.”

E3 (1/4 points) Is there freedom for trade unions and similar professional or labor organizations?

Iran does not permit the creation of labor unions; only state-sponsored labor councils are allowed. Labor rights groups have come under pressure in recent years, with key leaders and activists sentenced to prison on national security charges. Workers who engage in strikes are vulnerable to dismissal and arrest. Several detained labor activists received heavy prison terms of 14 years or more during 2019. One prominent figure, Sepideh Gholian, received temporary medical leave in August 2021 after reportedly receiving a COVID-19 diagnosis. However, Gholian was arrested in October after she publicly discussed the abuse of prisoners in Bushehr Central Prison.

Teachers held a three-day strike over pay and working conditions in December 2021. Rasoul Bodaghi, a board member of the Iran’s Teachers’ Trade Association, was arrested by security officers in Tehran in mid-December. Police officers forcefully dispersed a Tehran rally calling for his release two days later.

Rule of Law

F1 (1/4 points) Is there an independent judiciary?

While the courts have a degree of autonomy within the ruling establishment, the judicial system is regularly used as a tool to silence regime critics and opposition members. The head of the judiciary is appointed by the supreme leader for renewable five-year terms. Deputy head Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei was named to the judiciary’s top post in July 2021, succeeding then president-elect Raisi. Ejei previously served as an intelligence minister and prosecutor general.

Political dissidents and advocates of human and labor rights have continued to face arbitrary judgments, and the security apparatus’s influence over the courts has reportedly grown in recent years.

F2 (1/4 points) Does due process prevail in civil and criminal matters?

The authorities routinely violate basic due process standards, particularly in politically sensitive cases. Activists are arrested without warrants, held indefinitely without formal charges, and denied access to legal counsel or any contact with the outside world. Many are later convicted on vague security charges in trials that sometimes last only a few minutes. Lawyers who take up the cases of dissidents have been jailed and banned from practicing, and a number have been forced to leave the country to escape prosecution. In 2019, prominent human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh was reportedly sentenced to an additional 33 years in prison and 148 lashes for her activities; she had been in prison serving a five-year sentence since mid-2018. In October 2020, Sotoudeh was temporarily released amid concerns about her health following a hunger strike; she remained on leave as of July 2021.

In August 2021, authorities arrested five lawyers, a journalist, and a human rights defender (HRD) who were preparing a lawsuit against officials, alleging mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic. While three lawyers and the HRD were released by the end of August, lawyers Arash Keykhosravi and Mostafa Nili remained imprisoned as of December, along with journalist Mehdi Mahmoudian.

Dual nationals and those with connections abroad have also faced arbitrary detention, trumped-up charges, and denial of due process rights in recent years. In August 2021, German Iranian Nahid Taghavi and British Iranian Mehran Raouf both received separate 10-year and 8-month prison sentences on national security charges.

F3 (0/4 points) Is there protection from the illegitimate use of physical force and freedom from war and insurgencies?

Former detainees have reported being beaten during arrest and subjected to torture until they confess to crimes dictated by their interrogators. Some crimes can be formally punished with lashes in addition to imprisonment or fines. Political prisoners have repeatedly engaged in hunger strikes in recent years to protest mistreatment in custody. In September 2021, Amnesty International reported that at least 72 prisoners died in custody since January 2010; most of these deaths occurred due to torture, the use of firearms or tear gas, or ill-treatment.

Prisons are overcrowded, and prisoners often complain of poor detention conditions, including denial of medical care. Video footage taken in Evin prison and distributed in August 2021 captured incidents where prisoners were assaulted or mistreated, along with evidence of overcrowding. Criminal cases against six prison guards were opened later that month.

Prisoners risk contracting the novel coronavirus while in custody. Relatives of prisoners held in Evin reported an apparent rise in COVID-19 cases at the prison in July 2021 but also reported that COVID-19 testing was not consistently performed there. Writer and director Baktash Abtin, meanwhile, showed COVID-19 symptoms in April 2021 while imprisoned in Evin and was hospitalized in December after testing positive for COVID-19.

Iran has generally been second only to China in the number of executions it carries out, putting hundreds of people to death each year. Convicts can be executed for offenses other than murder, such as drug trafficking, and for crimes they committed when they were younger than 18 years old. Legislation enacted in 2017 significantly increased the quantity of illegal drugs required for a drug-related crime to incur the death penalty, prompting sentence reviews for thousands of death-row inmates. In August 2021, authorities executed Sajad Sanjari, who was originally arrested on murder charges as a minor in 2010. In November 2021, authorities executed Arman Abdolali, who was arrested on murder charges as a minor in 2014. Also in November, the United Nations noted that over 85 people were on death row for crimes they allegedly committed as minors.

Individuals who perform abortions may face the death penalty under a wide-ranging law ratified by the Guardian Council in November 2021. Under the law, large-scale abortion procedures may be considered acts of “corruption on earth,” a capital offense.

The country faces a long-term security threat from terrorist and insurgent groups that recruit from disadvantaged Kurdish, Arab, and Sunni Muslim minority populations.

F4 (1/4 points) Do laws, policies, and practices guarantee equal treatment of various segments of the population?

Women do not receive equal treatment under the law and face widespread discrimination in practice. For example, a woman’s testimony in court is given half the weight of a man’s, and the monetary compensation awarded to a female victim’s family upon her death is half that owed to the family of a male victim.

A majority of the population is of Persian ethnicity, and ethnic minorities experience various forms of discrimination, including restrictions on the use of their languages. Some provinces with large non-Persian populations remain underdeveloped. Activists campaigning for the rights of ethnic minority groups and greater autonomy for their respective regions have come under pressure from the authorities, and some have been jailed.

Members of the LGBT+ community face harassment and discrimination, though the problem is underreported due to the criminalized and hidden nature of these groups in Iran. The penal code criminalizes all sexual relations outside of traditional marriage, and Iran is among the few countries where individuals can be put to death for consensual same-sex conduct.

Personal Autonomy and Individual Rights

G1 (1/4 points) Do individuals enjoy freedom of movement, including the ability to change their place of residence, employment, or education?

Freedom of movement is restricted, particularly for women and perceived opponents of the regime. Many journalists and activists have been prevented from leaving the country. Women are banned from certain public places and can generally obtain a passport to travel abroad only with the permission of their fathers or husbands.

G2 (1/4 points) Are individuals able to exercise the right to own property and establish private businesses without undue interference from state or nonstate actors?

Iranians have the legal right to own property and establish private businesses. However, powerful institutions like the IRGC play a dominant role in the economy, limiting fair competition and opportunities for entrepreneurs, and bribery is said to be widespread in the business environment, including for registration and obtaining licenses. Women are denied equal rights in inheritance matters.

G3 (1/4 points) Do individuals enjoy personal social freedoms, including choice of marriage partner and size of family, protection from domestic violence, and control over appearance?

Social freedoms are restricted in Iran. All residents, but particularly women, are subject to obligatory rules on dress and personal appearance, and those who are deemed to have violated the rules face state harassment, fines, and arrest.

Police conduct raids on private gatherings that breach rules against alcohol consumption and the mixing of unrelated men and women. Those attending can be detained and fined or sentenced to corporal punishment in the form of lashes.

Women do not enjoy equal rights in divorce and child custody disputes. In 2019, the Guardian Council approved a legal amendment that would enable Iranian women married to foreign men to request Iranian citizenship for their children. The first identification cards for such children were issued in July 2021.

Iranians can receive an abortion within the first four months of a pregnancy if three doctors decide the mother’s life is at risk or if the fetus shows signs of severe disability. However, in November 2021, the Guardian Council ratified the Youthful Population and Protection of the Family Law; under the law, individuals seeking abortions will also require the approval of a committee that includes judicial representatives, Islamic jurists, doctors, and legislators. The law, which also bans the distribution of free contraceptives, can be used on an “experimental” basis for seven years.

G4 (1/4 points) Do individuals enjoy equality of opportunity and freedom from economic exploitation?

The government provides no protection to women and children forced into sex trafficking, and both Iranians and migrant workers from countries like Afghanistan are subject to forced labor and debt bondage. The IRGC has allegedly used coercive tactics to recruit thousands of Afghan migrants living in Iran to fight in Syria. HRW has reported that children as young as 14 are among those recruited.

The population faces widespread economic hardship driven by a combination of US-led trade sanctions and mismanagement by the regime. The crisis has resulted in the rapid devaluation of the national currency and soaring prices for many basic goods. Some Iranian officials have blamed the country’s poor handling of the COVID-19 pandemic on the effects of the sanctions. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the Secretary-General’s office expressed concern over the sanctions’ effects on living conditions in a May 2021 report. The United States did not make significant changes to its sanctions policy in 2021, however.