Iran achieved an escalating series of advances in its nuclear program—bringing it within days of so-called “breakout” capability—in the five years after the U.S. withdrew from the historic deal originally negotiated by the world’s six major powers. By May 2023, Iran had exceeded several of the key limits on nuclear activities. Meanwhile, repeated U.S. pressure by two presidents—including both new sanctions and diplomatic outreach—failed to revive the deal or contain Iran.

The changes over five years between 2018 and 2023 reflected gyrating U.S. policy on Iran as well as Tehran’s agility at exploiting the time. President Donald Trump abandoned the Iran nuclear deal on May 8, 2018. He also reimposed sanctions that had been lifted as the original incentive for Iran to make concessions limiting its program, then his administration applied more than 1,500 new sanctions. During the 2020 president campaign, Joe Biden vowed to return to the deal. But his diplomatic initiative launched in April 2021—led by the European Union and also including Russia and China—collapsed in August 2022 when Tehran balked at the final terms.

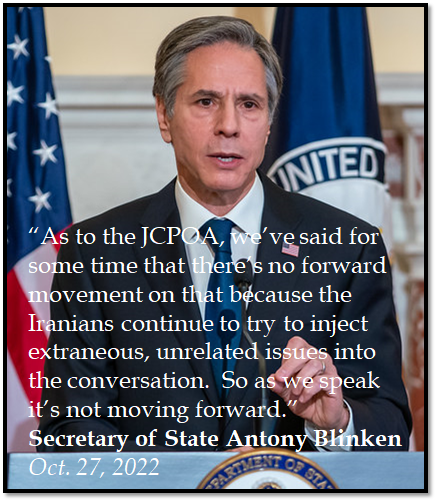

The Biden administration reversed course after protests, sparked by the death of a 22-year-old woman detained for improper dress, erupted across Iran’s 31 provinces in mid-September 2022. Hundreds were reportedly killed during four months of a ruthless government crackdown. The United States has “been clear that the Iran nuclear deal… is not now on the table,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in February 2023. On the fifth anniversary of the U.S. withdrawal from the deal, three experts—Kelsey Davenport of the Arms Control Association, Valerie Lincy of the Wisconsin Project and Naysan Rafati of the International Crisis Group—analyzed the Iran’s advances as well as U.S. strategy.

What was the U.S. strategy for addressing Iran’s nuclear advances five years later?

Kelsey Davenport: "The Biden administration’s general strategy for Iran draws from the typical U.S. two-pronged approach to proliferation threats: increasing pressure while offering a diplomatic offramp. Specifically, the Biden administration expressed its preference for a diplomatic resolution to address the Iranian nuclear crisis but made clear in the fall of 2022 that resuming negotiations was not a top U.S. priority given Iran’s unrealistic demands. Furthermore, senior officials have expressed doubt that the 2015 nuclear deal can be revived.

"Washington is open to a new diplomatic formula, most likely a smaller deal or set of reciprocal gestures, to reduce the current tensions. But it is looking for a sign that Tehran is interested in talks. With diplomacy at an impasse, the United States has continued to increase pressure on Iran through sanctions. It has also signaled willingness to use military force if necessary to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon. Washington’s pressure campaign, however, is hindered by the geopolitical rifts between the West and Russia as well as the United States and China. Moscow and Beijing are party to the nuclear deal but have increasingly supported Tehran’s stance and opposed sanctions."

"Washington is open to a new diplomatic formula, most likely a smaller deal or set of reciprocal gestures, to reduce the current tensions. But it is looking for a sign that Tehran is interested in talks. With diplomacy at an impasse, the United States has continued to increase pressure on Iran through sanctions. It has also signaled willingness to use military force if necessary to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon. Washington’s pressure campaign, however, is hindered by the geopolitical rifts between the West and Russia as well as the United States and China. Moscow and Beijing are party to the nuclear deal but have increasingly supported Tehran’s stance and opposed sanctions."

Valerie Lincy: "As of mid-2023, the United States seemed to have drifted into a hybrid strategy of pressure and negotiation. The Biden administration was still pursuing the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” policy: none of the additional sanctions that Trump imposed on broad swaths of Iran’s economy were suspended or lifted. At the same time, Washington actively engaged in negotiations and sought a mutual return to compliance with the JCPOA. Since late 2022, the scales have tilted toward pressure given Iran’s nuclear advances. Iran’s domestic repression and military support for Russia’s war in Ukraine further complicated diplomacy."

Naysan Rafati: "Until September 2022, the answer was reasonably straightforward in principle if not in practice: The Biden administration's preferred approach was to reverse those advances by negotiating a mutual return to compliance with the JCPOA, thereby restoring limits on Iran's nuclear activity and increasing international monitoring of its facilities. But four things happened that made an already-fraught process even more difficult:

- Tehran rejected a compromise text proposed by the European Union

- Russia began deploying Iranian drones against Ukraine

- Iran responded brutally to nationwide anti-government protests

- Concerns over Iran's failure to cooperate with the IAEA deepened

"By May 2023, the combination of these developments meant that there was little prospect of reviving the JCPOA, little in the way of diplomatic engagement and little clarity on what the new endgame should be."

What was the state of Iran’s nuclear program five years later?

Kelsey Davenport: "Iran has significantly expanded its nuclear program and invested in new capabilities during the past five years. In particular, Iran increased its uranium enrichment capacity by installing additional centrifuges, including advanced models that enrich uranium more quickly. In April 2021, Iran also began enriching uranium to a new level, 60 percent, which is close to the weapons-grade standard of 90 percent. The growing stockpiles of highly enriched uranium and additional centrifuges dramatically shortened Iran’s breakout time – the time needed to enrich enough uranium for one bomb. By May 2023, the breakout time was less than a week. More troubling, Tehran could produce enough uranium to fuel four weapons in about a month.

"Furthermore, Iran’s mastery of these new capabilities changed the paths available to Tehran if it decided to pursue nuclear weapons. In February 2021, Iran also suspended the U.N. nuclear watchdog’s access to certain facilities and blocked remote monitoring at those sites in June 2022. The transparency gap made it virtually impossible for the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to reconstruct an accurate history of Iran’s nuclear activities and reestablish inventory baselines in areas such as centrifuge production. Detecting and deterring a move to weaponization was also more difficult in 2023 due to the reduction in monitoring. In sum, the proliferation risk was much greater in May 2023 compared to May 2018, when Iran was abiding by the strict limits and intrusive monitoring required by the JCPOA."

Valerie Lincy: "The program was far more advanced in 2023 than it was in 2018 when Iran’s declared nuclear program was in compliance with JCPOA restrictions. When Trump pulled out of the JCPOA, Iran was, by most estimates, at least a year away from being able to produce enough highly enriched uranium for one nuclear weapon. That changed in 2019, when Iran started breaching the deal. Since early 2021, the program’s advances have brought Iran’s nuclear weapon capability well within the one-year milestone.

"By May 2023, the program had reached the point at which, within three to four weeks, Iran could be able to enrich enough uranium for five fission weapons. That material would still need to be processed further to produce a weapon."

Naysan Rafati: "The program was far more advanced and considerably less transparent. Iran began breaching its JCPOA commitments in 2019 and has since surpassed every major constraint, notably the levels of uranium enrichment and the size of enriched uranium stockpiles. The moves cut breakout time to–less than two weeks, although the United States has continued to assess that there has been no decision to weaponize. Iran also accumulated a non-quantifiable element of irreversible knowledge by working on, for example, increasingly sophisticated centrifuge models."

What was Iran’s strategy for diplomacy and advancing its nuclear program in 2023?

Kelsey Davenport: "In May 2019, Iran began breaching the JCPOA’s limits. It started by resuming nuclear activities prohibited under the deal, including:

- stockpiling enriched uranium beyond the 202-kilogram limit

- resuming uranium enrichment to 20 percent

- restarting uranium enrichment at Fordo

"While concerning, these activities were quickly reversible and did not result in Iran gaining any new knowledge that would erode the nonproliferation value of a restored JCPOA.

"Iran’s later breaches of the JCPOA expanded into new areas of research and mastery of new capabilities, such as enrichment to 60 percent and use of more efficient centrifuges, such as the IR-2 and IR-6 machines. The moves called into question Tehran’s commitment to returning to the JCPOA because the capabilities and the knowledge gains could not be fully reversed if the deal was restored. For example, when the JCPOA was implemented in 2016, Iran’s breakout time was about 12 months. Under a restored JCPOA, that timeframe would likely be about three or four months.

"Furthermore, Tehran responded to perceived provocations by ratcheting up its nuclear program. Iran’s advances and pattern of escalation raised questions about Tehran’s intentions. It could be building leverage to pressure the United States to lift sanctions. But it could also be better positioning itself in case the government decided to develop nuclear weapons."

Valerie Lincy: "Iran was using a tactic similar to the one it pursued in the years before the JCPOA: making procedural compromises just before an impending deadline and then backtracking. For example, it made last-minute concessions on inspector access prior to IAEA board meetings. But it delayed implementation or walked back commitments afterward. The result has been more nuclear advances with no real progress toward a negotiated agreement. The cycle has bolstered Iran’s strategy of (at a minimum) establishing a nuclear weapon capability as a guarantee of regime survival and gaining leverage at the negotiating table."

Naysan Rafati: "Iran continued to suggest an interest in concluding JCPOA negotiations. But what it regarded as acceptable terms went well beyond what the other parties deemed reasonable: closing IAEA investigations into past activities at undeclared sites or seeking guarantees for future adherence that the United States cannot provide. Tehran could continue advancing nuclear activities in a bid to increase leverage and prod Washington and its allies to re-engage diplomatically. But given Iran’s progress, it would be a risky gambit that could backfire through a referral to the U.N. Security Council via the IAEA Board of Governors, a restoration of pre-JCPOA sanctions initiated by Western powers, or even military action. But each scenario carried potential costs. Escalating the file diplomatically could prompt Tehran to respond on the nuclear front, and using covert operations or overt force could lead to both nuclear and regional retaliation. The lack of viable options has led to an uneasy situation in mid-2023."

Photo Credits: President Raisi via President.ir