Henry Rome is the deputy head of research at Eurasia Group. Follow him on Twitter @hrome2.

What are the most pressing political issues that Ebrahim Raisi faces at home?

Raisi is inheriting an array of challenges, including a fifth wave of the coronavirus pandemic, protests over water shortages and labor disputes, power outages, and continued economic volatility linked in part to the stalled nuclear negotiations. The pandemic continues to pose an acute threat in the near term. Iran this week recorded its highest number of daily new cases, as the Delta variant spreads and less than four percent of citizens are fully vaccinated.

Raisi and other hardliners will face these complex issues without a popular mandate or a coherent policy agenda. Raisi’s election was engineered to an unusual degree for a presidential election, reflecting both the leadership’s desire for Raisi to prevail and a lack of confidence he could win on his own. Most Iranians reacted by not casting their ballots, leading to the lowest turnout for a presidential race in the Islamic Republic’s history. Raisi has pledged to rebuild trust with the public, but this will be a significant challenge given the scale of public disillusionment.

Raisi and his allies will also face the challenge of not having anyone else to blame if their agenda falls short of expectations. Raisi’s election solidified conservative control over all levers of civilian government. Conservatives won control of the parliament in February 2020 and have long run the judiciary, where Raisi spent his career. While conservatives spent much of the past eight years blaming all of the country’s ills on Rouhani, they will no longer have the luxury of blaming rival factions.

What are the most pressing economic issues that Raisi faces at home?

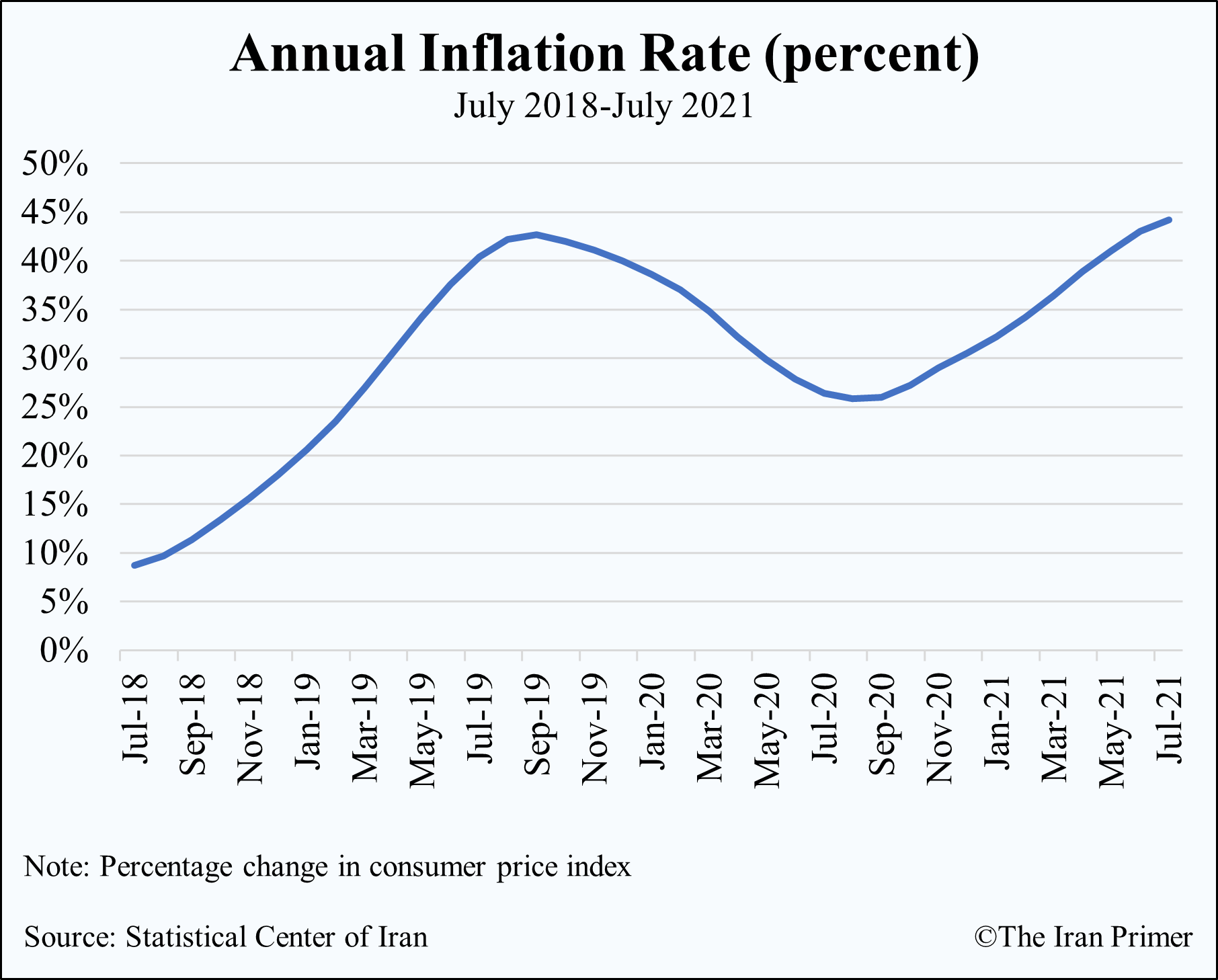

Raisi will take charge of an economy weakened by U.S. sanctions, the coronavirus pandemic, and chronic corruption and mismanagement. The International Monetary Fund expects economic output to grow by 2.5 percent in 2021-22, slower than in the previous year. Yet that rate is much stronger than during the height of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” sanctions campaign. At the same time, inflation has remained stubbornly high, eroding the purchasing power of Iranians. Consumer prices have increased 44 percent over the past year compared to the previous year. Unemployment stood at 9.6 percent in the previous Persian year (which runs from mid-March to mid-March), while unemployment among the youth between 15 and 25 was more than 23 percent. Meanwhile, the rial steadily depreciated against the dollar as nuclear talks between Iran and the world’s six major powers stalled and as Raisi’s election became reality.

Raisi will take charge of an economy weakened by U.S. sanctions, the coronavirus pandemic, and chronic corruption and mismanagement. The International Monetary Fund expects economic output to grow by 2.5 percent in 2021-22, slower than in the previous year. Yet that rate is much stronger than during the height of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” sanctions campaign. At the same time, inflation has remained stubbornly high, eroding the purchasing power of Iranians. Consumer prices have increased 44 percent over the past year compared to the previous year. Unemployment stood at 9.6 percent in the previous Persian year (which runs from mid-March to mid-March), while unemployment among the youth between 15 and 25 was more than 23 percent. Meanwhile, the rial steadily depreciated against the dollar as nuclear talks between Iran and the world’s six major powers stalled and as Raisi’s election became reality.

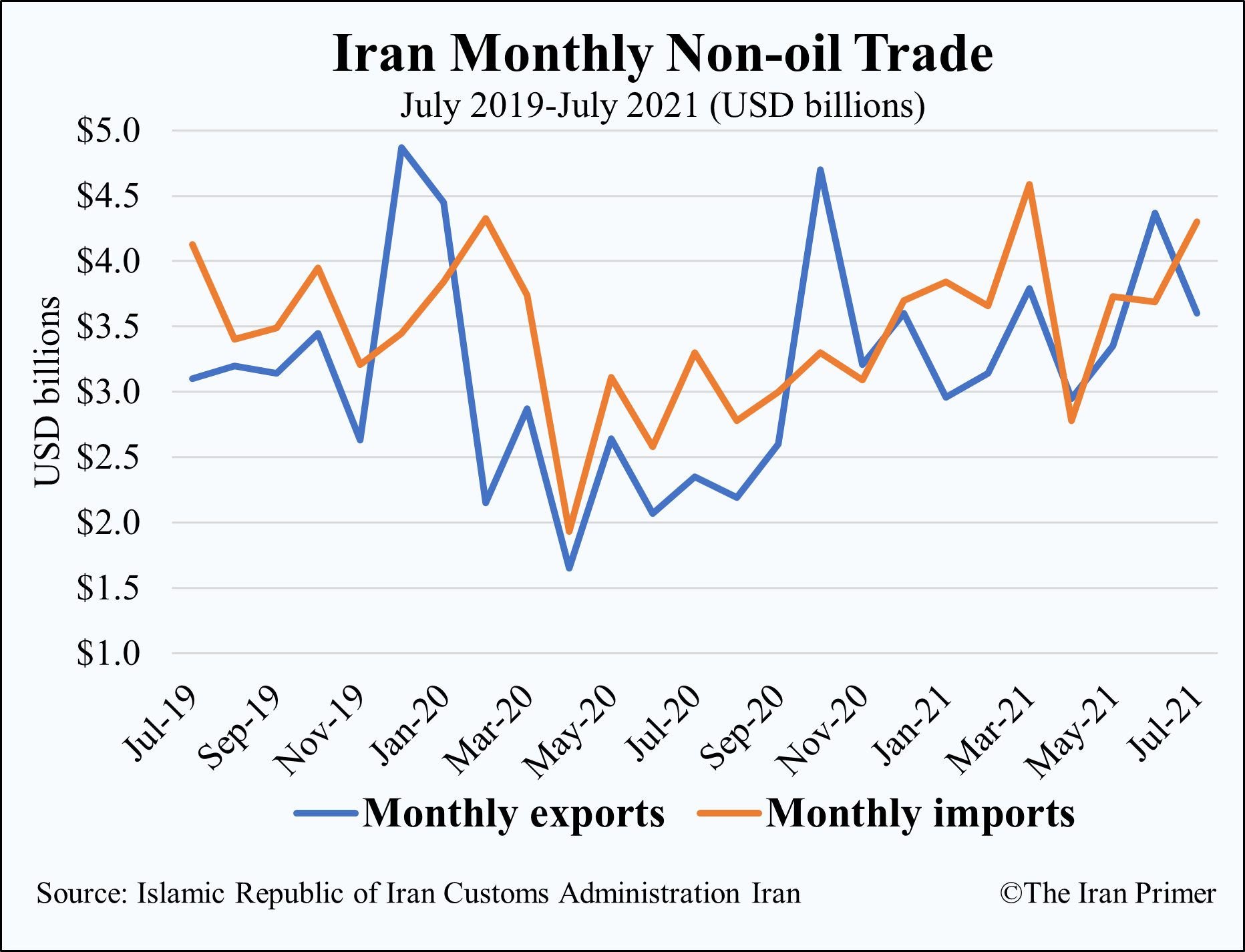

Relief from U.S. nuclear-related sanctions could go a long way toward stabilizing the economy. Sanctions relief would allow Iran to export more oil at higher prices, tap into some of its $100 billion in foreign exchange reserves frozen abroad, expand trading relationships, and access the international financial system. Rebuilding Iran’s financial connections should ease inflationary pressures and provide Raisi more fiscal breathing room early in his presidency. But there would probably be a low ceiling on the benefits of sanctions relief, as Raisi’s economic agenda will probably focus more on strengthening domestic capacities than on integrating Iran’s economy with Western businesses and financial institutions.

Relief from U.S. nuclear-related sanctions could go a long way toward stabilizing the economy. Sanctions relief would allow Iran to export more oil at higher prices, tap into some of its $100 billion in foreign exchange reserves frozen abroad, expand trading relationships, and access the international financial system. Rebuilding Iran’s financial connections should ease inflationary pressures and provide Raisi more fiscal breathing room early in his presidency. But there would probably be a low ceiling on the benefits of sanctions relief, as Raisi’s economic agenda will probably focus more on strengthening domestic capacities than on integrating Iran’s economy with Western businesses and financial institutions.

What is Raisi’s position on nuclear talks with the United States and major world powers? Is his position likely to differ from Hassan Rouhani’s?

Raisi has publicly supported the revival of the nuclear accord, so long as it is within the guidelines established by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. But the similarities between Raisi and Rouhani on the deal end there. Rouhani viewed the 2015 deal as potentially transformational for Iran, opening up the economy in key ways to the West and creating a “new chapter” for Iran’s international relations. Raisi takes a much more transactional view, arguing that relieving sanctions will be beneficial but that Iran should not count on it. In his post-election news conference, Raisi said, “We will not tie the Iranian people's interests to the nuclear deal,” underscoring Khamenei’s preference for “neutralizing” the effects of sanctions rather than relying on the West for their removal. Raisi also emphasized that the nuclear accord, regardless of its status, would not form the core of his policy agenda.

Raisi has given no more detail about his position on the nuclear talks, creating uncertainty about his negotiating strategy and team. One potential choice for foreign minister, Ali Baqeri-Kani, is a hardliner and veteran of the tumultuous nuclear talks under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Raisi’s attitude and allies, as well as recent comments from Khamenei, have elevated concern in the United States and Europe that Raisi will present new, untenable conditions when negotiations resume.

What are the other foreign policy challenges Raisi faces?

The president’s role in foreign policy is constrained, especially when it comes to regional policy. While he has a seat at the table, the president is not the ultimate decision-maker, so the change in administration will probably not sharply affect Iran’s regional policy. Yet two issues stand out as early challenges for Raisi, especially because they will rebound on domestic policy.

The evolving crisis in Afghanistan presents an immediate challenge. A Taliban takeover of most of the country could trigger large refugee flows into Iran, exacerbate the smuggling of illegal drugs, and threaten the minority Shiite community in Afghanistan. Iran has so far left its options open: It hosted a Taliban delegation in July while strengthening military deployments along the Afghan border. Iran is probably weighing whether to increase its historical support for the Taliban to enable greater control, or, alternatively, move its corps of Afghan fighters from Syria to defend against the Taliban. Negative spillover from Afghanistan could distract or subsume Raisi’s other priorities.

The evolving crisis in Afghanistan presents an immediate challenge. A Taliban takeover of most of the country could trigger large refugee flows into Iran, exacerbate the smuggling of illegal drugs, and threaten the minority Shiite community in Afghanistan. Iran has so far left its options open: It hosted a Taliban delegation in July while strengthening military deployments along the Afghan border. Iran is probably weighing whether to increase its historical support for the Taliban to enable greater control, or, alternatively, move its corps of Afghan fighters from Syria to defend against the Taliban. Negative spillover from Afghanistan could distract or subsume Raisi’s other priorities.

Raisi will also be responsible for dealing with the fallout from the decades-long proxy conflict with Israel. Raisi will probably have limited influence on the trajectory of the conflict, but he will be on the hook to grapple with potential future cyberattacks and other forms of sabotage against Iranian civilian and nuclear infrastructure. As with Raisi’s domestic political and economic challenges, he will be unable to credibly blame moderates for their failure to safeguard Iranian interests.

How is Raisi likely to be different than Rouhani?

The two clerics are different in a number of ways, but two distinctions are worth noting. First, if the nuclear deal is implemented, Raisi will have a different attitude than Rouhani did about foreign investment and engagement. Rouhani toured Europe to entice investment and fought domestic battles to reform Iran’s dismal business environment. Raisi will probably have little interest in bolstering Western economic ties and will probably invest the deal’s economic benefits in strengthening the country’s independence and resilience against future sanctions. On August 3, he pledged not to tie the economy to “the will of foreigners.”

Second, Raisi will probably have a different attitude toward social and political rights at home. For many Iranian reformists, Rouhani’s two terms were a disappointment. Despite a slew of campaign promises, Rouhani delivered little in the way of social and political liberalization. Yet many fear that Raisi’s presidency will be far worse, and feature more repression and suppression of dissent. Raisi led a judicial branch that has been accused of gross human rights abuses, including torturing and executing political prisoners. He also led the crackdown against the 2009 Green Movement protests and against subsequent unrest. Raisi is also well known for his role in the killing of thousands of political prisoners in 1988. With conservative hegemony across all major state institutions, there are few safeguards left to prevent further deteriorations on human rights.