By Garrett Nada with Thomas Neal, Cameron Glenn and others

Since 1979, Iran’s theocracy and Saudi Arabia’s monarchy have vied for regional dominance. Their competition has played out politically, militarily, economically, and culturally—and regularly in rhetoric. In 1987, revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini said, “These vile and ungodly Wahhabis are like daggers which have always pierced the heart of the Muslims from the back.” He declared that Mecca was in the hands of “a band of heretics,” a statement which led to a four-year break in diplomatic relations. Saudi leaders have also used tough language. In a 2018 interview, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman compared Iran’s second supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to Adolf Hitler. “I believe the Iranian supreme leader makes Hitler look good. Hitler didn’t do what the supreme leader is trying to do. Hitler tried to conquer Europe. … The supreme leader is trying to conquer the world.”

The key flashpoints between the Gulf hegemons include:

- In May 1981, Saudi Arabia created the Gulf Cooperation Council with five other Sunni-led sheikhdoms—Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates—to counter the rise of a Shiite revolutionary regime in Iran.

- Throughout the 1980s, relations were deeply strained, as Saudi Arabia supported Iraq during its eight-year war with Iran.

- In May 1984, Iran attacked a Saudi oil tanker in Saudi water, in retaliation for Iraq’s attempts to interfere with Iran’s oil shipping. Saudi Arabia shot down an Iranian Phantom jet over Saudi waters.

- In July 1987, a demonstration by Iranians against “the enemies of Iran” during the annual hajj pilgrimage in Mecca led to clashes with Saudi security forces and the death of more than 400 people—including 275 Iranian pilgrims and 85 Saudi police. In response, Iranian protesters attack the Saudi and Kuwaiti embassies in Tehran. In 1988, Saudi Arabia severed ties with Iran. Riyadh reduced the number of Iranian visas for the hajj. Iran boycotted the pilgrimage from 1988 to 1990.

- In June 1996, a massive truck bomb hit Khobar Towers, a U.S. military barracks in Dhahran, killing nineteen U.S. servicemen and wounding hundreds. Iran was blamed.

- In 2011, the U.S. accused Iran of using a car salesman from Corpus Christi Texas to plot the assassination of the Saudi ambassador in Washington.

- In March 2011, Saudi Arabia sent troops to quell the Shiite protests in Sunni-ruled Bahrain during the Arab Spring uprisings; it blamed Iran for provoking the unrest.

- In 2012, a series of protests against anti-Shiite discrimination erupted in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. Saudi Arabia blamed Iran for the protests.

- In September 2015, hundreds of Iranians were killed in a stampede during the annual hajj in Saudi Arabia. Tehran accused Riyadh of mismanagement, and Saudi officials accused Iran of playing politics in the aftermath of the tragedy.

- In January 2016, Iranian protesters attacked the Saudi embassy in Tehran after Saudi Arabia executed Shiite cleric Nimr al Nimr. Riyadh severed diplomatic ties with Tehran.

- In March 2015, a Saudi-led coalition launched the first airstrikes against Houthi rebels, backed by Iran, after they seized control of much of Yemen.

- In June 2017, tensions escalated after the appointment of Saudi King Salman’s son, Mohammed bin Salman, as crown prince.

- In September 2019, Saudi Arabia blamed Iran for airstrikes on two major oil installations, at Abqaiq and Khurais, which disabled more than half of its oil production.

Rapprochement Outreach

After the Iran-Iraq war ended in 1988, both Saudi Arabia and Iran attempted to improve their rocky relationship.

- In 1989, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanji was elected to Iran’s presidency. He took a more conciliatory stance towards Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf countries. Under Rafsanjani's two terms (1989 to 1997), trade and direct flights between the two countries increased.

- In June 1990, Saudi Arabia sent aid to Iran after an earthquake killed 40,000 people.

- In March 1991, the two countries restored diplomatic relations.

- In December 1997, Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah visited Iran for a meeting of the Organization of the Islamic Conference. He was the most senior Saudi leader to visit Iran since the 1979 revolution.

- In February 1998, former President Rafsanjani visited Saudi Arabia. He was the most senior leader to visit the kingdom since the 1979 revolution. He was accompanied by a delegation including Oil Minister Bijan Namdar Zanganeh. The two countries discussed ways to deal with low oil prices.

- In 1997, Mohammad Khatami was elected to Iran’s presidency. During his two terms (1997 to 2005), he attempted to improve Iran’s relations with the outside world, including adversaries such as the United States and Saudi Arabia.

- In May 1999, President Khatami made an historic visit to Saudi Arabia, part of an eight-day tour of Arab states. King Fahd said it opened the door to strengthening bilateral ties. “In the future, if the two governments have the political will, there are no limits to co-operation with Iran,” he said.

- In April 2001, after two years of talks, the two countries signed a landmark security accord on stopping terrorism, drug trafficking and organized crime. Saudi Interior Minister, Prince Nayef bin Abdul Aziz, went to Tehran to sign the agreement.

- In 2005, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected to Iran’s presidency. He took a more hardline stance on foreign policy. During his tenure (2005 to 2013), Tehran and Riyadh increasingly sought to boost their regional influence through proxies in Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

- In March 2007, President Ahmadinejad visited Saudi Arabia for talks with King Abdullah on curbing sectarian strife in the region, especially Iraq.

- 2013-Present: Hassan Rouhani was elected to Iran’s presidency in 2013 on a platform of “prudence and hope.” He promised to solve the row over Iran’s controversial nuclear program and improve the economy by improving relations with the outside world.

- In December 2013, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif went on a tour of Gulf Arab states, including Kuwait, Oman and Qatar – but not Saudi Arabia. But he emphasized that Tehran was keen on improving relations with Riyadh. “We believe that Iran and Saudi Arabia should work together in order to promote peace and stability in the region,” he told the press. He had said the government of new President Hassan Rouhani had two top foreign policy goals—a nuclear deal ending tensions with the outside world and repairing relations with the Saudi-led Gulf.

Vying for Leadership in the Islamic World

Saudi Arabia is the cradle of Islam and home to the faith’s two holiest cities, Mecca and Medina. The Sunni kingdom sees itself as the natural leader of the Muslim world. The ruling family has strong ties to Wahhabism, a conservative form of Sunni Islam. Clerics do not play a formal role in government but are powerful players in the kingdom. With growing wealth after the 1973 quadrupling of oil prices, Riyadh more aggressively promoted Wahabbism by funding mosques, missionaries and schools. Saudi Arabia provided some $4 billion in aid to the mujahideen in Afghanistan to fight the Soviet occupation between 1979 and 1989. In 1992, King Fahd claimed in an address to the nation that the kingdom had “become a distinguished model of politics and government in modern political history.” Loosely monitored charities based in the kingdom have reportedly funded Sunni militant groups, including al Qaeda, the Taliban and Hamas.

Iran views its Shiite-dominated theocracy, with a constitution partly based on French and Belgian law and led by elected officials, as a worthier model than an autocratic monarchy dependent on the United States. In 1979, revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini called for overthrowing pro-American monarchies in the Gulf, including Saudi Arabia. In the early years after the revolution, Iran tried to export its ideology, most successfully with the creation of Hezbollah in Lebanon in 1982. Since the 1980s, Iran has also provided arms, training or funding to militias in Syria, Iraq, the Palestinian Territories, and Yemen, with mixed results.

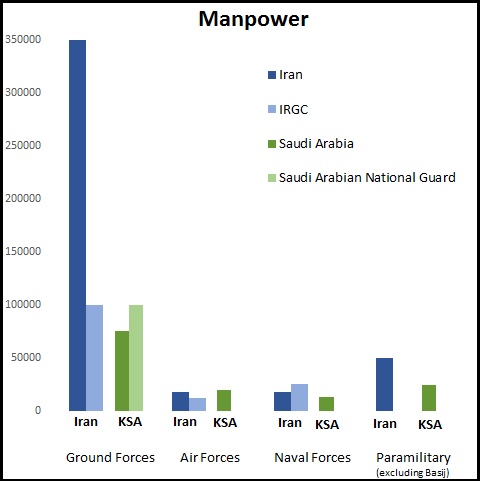

Disparate Military Capabilities

Saudi Arabia had the third largest defense budget in the world in 2017. It has increased its defense spending as regional tensions have escalated. Its official budget in 2017 reportedly totaled nearly $65 billion—almost $55 billion more than Iran’s budget. In 2018, Saudi Arabia spent some $67 billion on defense. Between 2014 and 2018, it was the world's largest arms importer.

Saudi Arabia has invested deeply in conventional military equipment and training. The kingdom is the number one importer of U.S. and British military goods. It has also benefited from the stationing of U.S. troops in the Gulf. But Saudi troops have been slow to learn how to use cutting-edge equipment, such as Patriot missile systems purchased from the United States. The military has also been plagued by rampant nepotism, skewing leadership appointments, despite Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s pledge to crack down on corruption within the military. The Saudi Army is not well-prepared for offensive operations, which may be one reason it has relied on missile and air strikes rather than directly engaging its ground forces in Yemen.

The real strength of the Saudi military lies in the Royal Air Force. Riyadh has invested billions of dollars to project power over long distances. The Air Force proved its effectiveness by flying almost 100,000 sorties over Yemen between 2015 and 2018. By controlling the skies, Saudi Arabia could effectively control the battle space in a conventional war.

In terms of manpower, Saudi Arabia has conventional ground, air and naval forces. Its paramilitary Border Guard—of roughly 10,500—operates separately under the Ministry of Interior. It also has a Coast Guard of 4,500 men, plus a Facilities Securities Force of 9,000 troops under the Ministry of Interior. The kingdom relies on its conventional forces and its partnership with the United States to protect its interests.

Source: “The Military Balance 2018” – The International Institute for Strategic Studies (with permission)

In contrast, Iran has a serious shortage of modern military equipment, largely due to sanctions and arms embargoes imposed after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. It has been forced to rely on arms from China and Russia. Out of necessity, Tehran has developed its own military industrial complex. Iran lacks modern tanks, warplanes, and naval warships but it has built a substantial arsenal of missiles.

Iran has invested heavily in its missile program to make-up for the lack of a modern air force. It has the largest and most diverse ballistic missile arsenal in the Middle East. It has the capability to strike as far as Jerusalem using variants of the North Korean Nodong missile. Russia has also sold Iran S300 surface-to-air missiles to Iran, which improved its air defenses.

Iran has also invested in developing unconventional warfare abilities—at home and with regional proxies—far more than Saudi Arabia has. Its influence is visible in Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Yemen’s Houthi rebels, Shiite militias in Syria and Iraq, and Palestinian Hamas and Islamic Jihad. Iran has exploited unrest in the region, deploying its forces and gaining valuable experience in unconventional wars. Iranian military officers have advised, trained, armed, and gone into battle with some of the foreign militias.

Iran’s military includes conventional ground, air and naval forces. It also has separate revolutionary forces, ranging from highly trained troops to poorly equipped volunteers.

In addition, Iran has built a large paramilitary. The Basij is an auxiliary force under the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). It is tasked largely with internal security. It has 90,000 active forces, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies. But the Basij can mobilize up to 1 million. Iran also has smaller paramilitary units for border security and law enforcement. Iran has worked extensively with Shiite militia groups to extend its influence in the region.

Click here for more information on the Iranian and Saudi militaries.

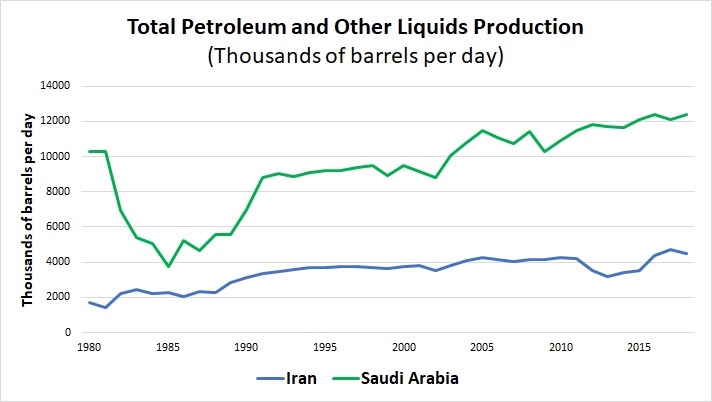

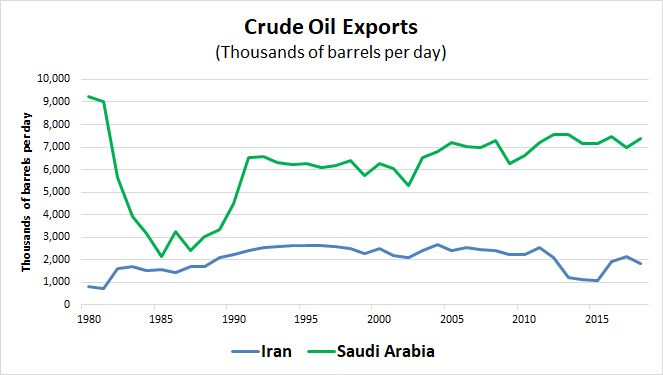

Oil Output

In Saudi Arabia, oil was first discovered in 1938. State-owned Saudi Aramco has continued to discover new fields, as recently as 2016. The largest exporter of petroleum liquids is home to some 16 percent of the world’s proved oil reserves spread among some 130 fields.

Saudi Arabia has the capacity to produce 12 million barrels per day (bpd). The oil and gas sector accounts for some 50 percent of the kingdom’s gross domestic product, and 70 percent of export earnings.

In 1908, Iran was the first country in the Persian Gulf to discover oil. Its oil sector is one of the oldest in the world. As a result, Iran has one of the world’s most mature oil sectors. About 80 percent of its reserves were discovered before 1965. Iran has already produced more than 75 percent of its reserves, so the likelihood of other major discoveries is low. Iran is home to almost 10 percent of the world’s crude oil reserves.

Source: Central Intelligence Agency (2004)

Over the years, Washington has imposed escalating waves of sanctions on Tehran, many of which targeted the oil and gas industry. In 2010, it produced some 3.54 million bpd, though by early 2015 production had dropped to around 3 million bpd. In 2011 and 2012, the United States and European Union imposed the harshest round of sanctions to date. By 2014, Iran’s oil exports plummeted from 2.5 million bpd to 1.4 million bpd, their lowest levels since 1986. During this period, Saudi Arabia's oil exports remained relatively high.

Source: OPEC

In 2015, Iran and six major world powers brokered a landmark agreement that provided Tehran with sanctions relief for curbing its nuclear program and allowing intrusive U.N. inspections of its facilities.

Oil exports and production picked up after the deal went into implementation in January 2016. But President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, in May 2018. The administration then reimposed sanctions on Iranian banks, the national oil company, and other key economic actors. By August 2019, its oil exports were down to 160,000 bpd, down from 2.7 million bpd in May 2018.

Click here for more information on Iran’s oil and gas industry.

Regional Influence

Yemen

Saudi Arabia and Iran have been involved in a proxy war in Yemen since at least 2015. Iran is widely accused of backing the Houthis, a Zaydi Shiite movement that has been fighting Yemen’s Sunni-majority government since 2004. The Houthis took over the Yemeni capital Sanaa in September 2014. In March 2015, a Saudi-led coalition launched a military intervention in support of the central government and President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi.

Yemeni officials and Sunni states have repeatedly alleged that Iran and its proxy Hezbollah have provided arms, training, and financial support to the Houthis. But Iranian and Hezbollah officials have denied or downplayed the claims. In November 2017, Revolutionary Guards commander Maj. Gen. Ali Jafari said that “Iran’s assistance is at the level of advisory and spiritual support.” But the United States, in coordination with Saudi Arabia, has presented physical evidence of Iranian arms transfers to the group.

The Houthis have held out despite years heavy aerial bombardment by Saudi and Emirati warplanes. The group has launched scores of cross-border attacks on Saudi targets using ballistic missiles, drones and rockets.

Click here for more information about the Houthis.

Lebanon

Riyadh and Tehran have supported rival groups inside Lebanon. In 1982, Iran's Revolutionary Guards played a critical role in establishing the underground movement that evolved into Hezbollah. By 2019, the group dominated politics and had the most well-armed and trained militia in the region.

Riyadh has tried to curb Iranian influence in Lebanon through supporting the Lebanese state as well Sunni allies, including the influential Hariri family. Rafiq Hariri, a former prime minister, reportedly made billions of dollars in the Saudi construction business. He was assassinated in 2005. Four Hezbollah members were indicted in 2011 by an international tribunal for the murder. Rafiq’s son, Saad Hariri, served as prime minister from November 2009 to June 2011, then again starting in 2016. He is a dual Saudi-Lebanese citizen.

One dramatic episode involving Hariri in 2017 was a microcosm for Saudi and Iranian influence in Lebanese politics. On November 4, Hariri announced his decision to resign from Riyadh on the Saudi-owned Al Arabiya television station. He blamed Iran and Hezbollah for destabilizing the region and claimed that there was a plot on his life.

Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah accused Saudi Arabia of forcing Hariri to resign. Iran also accused Saudi Arabia of meddling. But Foreign Minister Adel al Jubeir called that charge nonsense. Hezbollah pushed Hariri to resign “by hijacking the political system” and “threatening political leaders,” he countered. Thamer al Sabhan, the Saudi minister for Gulf affairs, escalated the situation on November 7 by accusing Hezbollah of involvement in every “terrorist act” that threatened the kingdom. Lebanon’s government would be “dealt with as a government declaring war on Saudi Arabia,” he warned. On November 9, the kingdom told its citizens to leave Lebanon immediately.

The situation eventually calmed down. Hariri returned to Lebanon on November 22 after visiting Abu Dhabi, France, Egypt, and Cyprus. He announced that he was putting his resignation on hold and that he planned to stay in Lebanon.

Iraq

Iran is the dominant foreign player in Iraqi politics. Iran and Iraq are Shiite-majority countries that share centuries-deep cultural and religious ties — and a 900-mile border. Since U.S.-led forces toppled Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, the Islamic Republic has used these advantages to permeate Iraq’s political, security, economic, and religious spheres. The country’s most powerful militias have received support from Iran and some have even pledged their allegiance to Supreme Leader Khamenei. Iran also has close ties to Iraq’s major Shiite politicians, many of whom sought asylum in Iran in the early 1980s, during the Iran-Iraq War.

Since 2014, Iranian officials have made provocative claims about their influence over their western neighbor. In 2014, Iranian lawmaker Ali Reza Zakani famously said Iran controlled four Arab capitals —Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus, and Sanaa.

Saudi Arabia has been absent from the Iraqi arena for nearly three decades. It cut ties with Iraq after the invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Riyadh only resumed diplomatic relations with Baghdad in 2015. Adel al Jubeir visited Iraq in 2017, the first time a Saudi foreign minister had visited in 27 years. Saudi Arabia finally reopened its consulate in Baghdad in April 2019, amid a wider effort to counter Iranian influence. Riyadh is essentially building relationships from scratch. “Saudi policymakers are clear-eyed about how long it could take to dent Iranian influence,” according to Elizabeth Dickinson, a senior analyst at the International Crisis Group. “They understand that Iraq will need to be more economically buoyant before it can start to make stronger choices about who it does and doesn’t partner with—something they estimate could take five to 10 years.”

Click here for more information about Iran’s role in Iraq.

Click here for more information about Iran-backed militias in Iraq.

Syria

Saudi Arabia and Iran have supported opposing actors in Syria’s civil war. Iran has sent military advisors, oil, financial aid, and equipment to the Assad regime. It has organized Shiite militias from as far as Afghanistan and Pakistan to fight the rebels and Islamist militants. Riyadh saw an opportunity in the conflict to help oust a critical ally of Iran and conduit to Hezbollah in Lebanon. It funded Sunni rebels fighting the regime, including the U.S.-backed Free Syrian Army. Saudi Arabia surpassed Qatar as the primary backer of the rebels in 2013. But the Assad regime retook the vast majority of territory by 2019, backed by Russian airpower and a wide array of Iran-backed militias.

Qatar

Qatar, a small Sunni emirate, has always occupied a unique space between Saudi Arabia and Iran. It shares a land border with Saudi Arabia but it shares a natural gas field – by far the world’s largest – with Iran. Doha and Iran had a tense relationship for decades until June 2017, when five countries – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain and Egypt and Maldives – accused Qatar’s al Thani royal family of financing terrorism and promoting instability across the Middle East. The bloc made thirteen demands of Doha; the first was to break military and political ties with Tehran, long accused of supporting opposition groups in the Gulf. Out of necessity, Qatar-Iran relations improved almost overnight. Iran started shipping massive quantities of food. The two countries restored full diplomatic ties in August. In December, Saudi Arabia closed its land border with Qatar.

Click here for more information about Iran’s relationship with Qatar.

Bahrain

Bahrain is a small country located just off the coast of Saudi Arabia’s eastern coastline. The Sunni al Khalifa clan has ruled the Shiite-majority populace since 1783. Manama has historically sided with Riyadh on issues where Iran was involved. In March 2011, the Arab uprisings spread to Bahrain. Saudi Arabia’s military intervened to quell the unrest among Shiites. Bahrain has long accused Iran of fomenting insurrection or supporting terrorists. U.S. officials observed an uptick in insurgent activity among Iran-backed groups in 2017 and 2018. Bahrain’s chief of public security said groups including the al Ashtar Brigrades and al Mukhtar Brigades were responsible for 22 deaths and more than 3,500 injuries to police between 2011 and 2018. In April 2019, Bahrain stripped 138 people of their citizenship for alleged links to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Garrett Nada, managing editor of The Iran Primer at the U.S. Institute of Peace, contributed to this report, which builds on previous articles and chapters by Cameron Glenn, Mattisan Rowan, Thomas Neal, Evan Burt, and Fareed Mohamedi.