On January 8, former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani died of a heart attack at age 82. He held top positions in the Islamic Republic since the 1979 revolution. He was president for two terms from 1989 to 1997. He was chairman of the Assembly of Experts, a panel of more than 80 clerics and scholars who oversee the supreme leader, from 2007 to 2011. And he was chief of the Expediency Council, the ultimate arbiter of disputes between parliament and the 12-man Guardian Council. Rafsanjani’s status gave him a little bit of protection that allowed him to remain a political player for nearly four decades. He was speaker of parliament for nine years in the 1980s.

But more than titles, Rafsanjani was long the behind-the-scene powerbroker in the world’s only modern theocracy. His death reflects the deep division that permeates the Iranian revolution as it nears its 38th anniversary.

Centrists, pragmatic conservatives and reformers, meanwhile, have lamented the passing of a key ally. They include President Hassan Rouhani, who faces reelection in May. The coalition that supported Rouhani may be more vulnerable without Rafsanjani’s backing. “Today, Islam lost a valuable asset; Iran a great figure; Islamic Revolution a brave guide; the state a wise, unparalleled figure,” Rouhani said in a statement. He declared three days of public mourning. Hardliners, who often opposed Rafsanjani’s attempts at reform, may feel that the balance has shifted more to their advantage without the elder leader looming in the background.

Rafsanjani's face was ubiquitous on news stands on January 9. The following are developments since his passing, reactions from Iran and around the world and a profile of the late leader.

US Reaction

In an unusual statement, a U.S. official commented on Rafsanjani's death:

“Former President Rafsanjani has been a prominent figure throughout the history of the Islamic Republic of Iran. We send our condolences to his family and loves ones.

“We are not going to debate history, comment on the potential internal implications of his death or its potential impact on Iran’s decision making. He was a consequential figure inside of Iran and we send our condolences to his family and loved ones. We don’t have any further comment.”

On January 9, State Department spokesperson John Kirby commented during the daily press briefing:

“I mean, former President Rafsanjani has been – or was, excuse me – a prominent figure throughout the history of the Islamic Republic of Iran, and we do extend our condolences to his family and to his loved ones.”

“[H]e was a prominent figure, and the history’s complicated. We’re not going to debate the history, and I don’t think it’s valuable for us to try to comment on the potential internal implications of his death, of the potential impact on Iran today. He was consequential in terms of the recent history of Iran and we send our condolences to the family and loved ones. And whatever there is to say about his complicated history, you’re still dealing with a family that’s dealing with grief and dealing with a loss, and so it’s not inappropriate for us to simply offer our thoughts to a family that’s grieving right now.”

Major Developments since Rafsanjani’s Death

Rafsanjani’s middle son, Mehdi Hashemi, currently serving a 10-year sentence for security and financial crimes, was released from prison to mourn his father.

Mehdi Hashemi, the son of #Rafsanjani, was brought in from the notorious Evin prison to visit his father's coffin. pic.twitter.com/04i5Ey72Jp

— Rohullah Yakobi (@Roh_Yakobi) January 8, 2017

In the following video, Mehdi Hashemi appears to prevent state television chief Ali Asgari from escorting Rafsanjani’s body during a procession.

مهدی هاشمی به رییس سازمان صدا و سیما اجازه نداد زیر تابوت آقای هاشمی را بگیرد... pic.twitter.com/MrJYHBFnta

— H.Soleimani (@MashreghNews_ir) January 9, 2017

Former President Mohammad Khatami was allowed to pay his respects in the town of Jamaran, where late revolutionary Ayatollah Khomeini once lived. Since 2010, Khatami has been banned from leaving the country and barred from public events or quotes in the media. He has skirted the ban by using social media. Khatami was barred from attending Rafsanjani’s funeral.

وداع با پیکر آیت الله هاشمی_رفسنجانی در حسینیه جماران pic.twitter.com/3RHGYb6b4q

— KhatamiMedia (@Khatamimedia) January 8, 2017

More than 2 million people reportedly participated in Rafsanjani’s funeral procession.

Hashemi Rafsanjani's funeral procession. Some reports indicate that more than 2 million people attended. #Iran #hashemirafsanjani pic.twitter.com/uzHTNvrxs2

— Reza H. Akbari (@rezahakbari) January 10, 2017

Mourners chanted pro-opposition slogans so loudly that state television played music during the broadcast to drown the sound out. Some yelled “hail to Khatami” and Mir Hossein Mousavi’s name, the leader of the Green Movement who has been under house arrest for nearly six years.

صدای مراسم تشییع پیکر آیتالله/حجتالاسلام والمسلمین #هاشمی_رفسنجانی از #صداوسیما پخش و بعد از شعار درود بر هاشمی، سلام بر #خاتمی قطع شد pic.twitter.com/huhX8d6Zk8

— مملکته (@mamlekate) January 10, 2017

The government also reportedly cut cell phone service and slowed down Internet access during the event. In the video below, a woman asks “why did you cut mobiles and Internet?”

من به عشق آقای خاتمی اومدم

— کو کو (@kourosh721) January 10, 2017

از هیچی هم نمیترسم...#هاشمی_رفسنجانی#وداع pic.twitter.com/qyt8SYxcAb

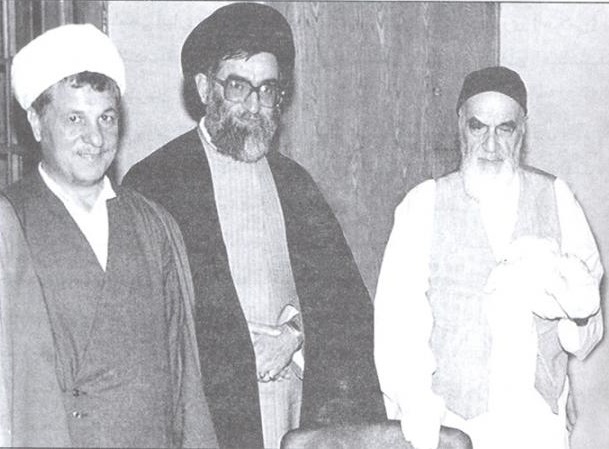

Rafsanjani was buried in Ayatollah Khomeini’s mausoleum, a high honor even for a former president. The two had a close relationship.

Reactions from Iran

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

Ayatollah Khamenei in a message expressed condolences over demise of Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani. pic.twitter.com/fLvD2YtdVq

— Khamenei.ir (@khamenei_ir) January 8, 2017

It was with grief and regret that I received the news of the demise of my old friend, my comrade in arms and my associate during the Islamic revolutionary movement and my close colleague over the course of many years in the Islamic Republic era – Hujjatul Islam wal Muslimeen Hajj Sheikh Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.

The loss of a comrade in arms and associate with whom I had a 59-year experience of cooperation, harmony and collaboration is difficult and excruciating. What difficulties and adversities occurred to us in these decades and what cooperation and collaborations we had together in many periods of time on a common path that was marked by diligence, endurance and risk taking!

His abundant intelligence and his unique sincerity in those years was a reliable source of support for all those who worked with him, particularly for myself. Differences of opinion and varying “ijtehads” at certain stages of this long era could never break a bond of friendship whose starting point was in Bayn-ul-Haramayn [the area between the two shrines of Imam Hussein (a.s.) and Hazrat Abbas (a.s.)], in the holy city of Karbala. And the temptations of devils which were seriously and arduously trying to take advantage of those differences of opinion in recent years, could never influence his deep individual affection for humble me.

He was a peerless example of the first-generation of fighters against monarchic oppression and he was one of those who suffered on this perilous and glorious path. Years of prison, endurance of SAVAK tortures and resistance in the face of all these and then crucial responsibilities during the Sacred Defense Era, the chairmanship of the Islamic Consultative Majlis and the Assembly of Experts and other such responsibilities are some of the bright pages in the eventful life of that old fighter.

With the loss of Hashemi, I know no other personality with whom I had such a common and long-term experience in the peaks and valleys of this historic era.

Now this old fighter is in the presence of divine accounting with a performance sheet which is filled with diligence and various activities and this is the fate of all of us officials of the Islamic Republic.

I beseech God from the bottom of my heart to bestow His forgiveness, mercy and clemency on him and I express my condolences to his esteemed wife, to his children and brothers and to his relatives.

God’s forgiveness be upon us and upon him.

President Hassan Rouhani

Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani was Rouhollah [Khomeini]'s steadfast son, long-standing companion of the leader, distinguished and history-making figure of Islamic Revolution and somebody who was truly sympathetic towards people. How meaningful it was in history that the legend of faith, patience, tolerance and moderation passed away on the very day that people's uprising in defending the great Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Revolution.

Taking about Hashemi, whom I was beside for many years, is very difficult. He was a perfect example of a revolution-backer during the Iranian nation's fight under the leadership of late Imam. Years of prison and torture did not separate him from that path. He always was one of the distinguished forerunners of the Islamic Revolution. It was him who never left Imam alone from Qom to Najaf, and from Paris to Tehran. Hashemi is among the distinguished architects of the Islamic Republic of Iran; the Constitution, the Islamic Consultative Assembly, the Assembly of Experts of Leadership, the Presidency, the Expediency Discernment Council of the System, the Islamic Republic Party, the Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution, the Construction Jihad and all institutions of the Islamic Revolution are indebted to this man of future and his wisdom and foresight.

Today, Islam lost a valuable asset; Iran a great figure; Islamic Revolution a brave guide; the state a wise, unparalleled figure.

He was loved by Imam [Khomeini] and a servant to people. Wherever he was responsible for, he was a source of serenity for Imam, the leader and the people. He was a capable analyst and knew the world well. His sermons during the hard times of the Sacred Defence filled people with tremendous spirit. In being subject to persecution, he was like his old companion, martyr Ayatollah Beheshti, easily enduring ingratitude.

Hashemi never feared war and always sought peace; he was both a courageous commander of Jihad and martyrdom, and the hero of negotiation for ending the war. Talking about a man who truly was the foundation of state is not easy. He was Imam's confidant and the Supreme Leader's incomparable companion. He had lofty wishes for Iran and Iranians and made tireless efforts for the pride of our Islamic homeland until the last moment of his life. He was subject to unkindness and showed loyalty. He did not agree with deviating from the path of moderate Islam and considered the expediency of the system above all things. The understanding people of Iran are grateful of their servants and will pay their debts to the Commander of Construction.

Hashemi's name is so great that nobody can deny his effective role in every page of the history of the Islamic Movement from the first campaigns in the 1340s until the victory of the revolution and from his incomparable and excelling history in managing the country through the Sacred Defence era to all critical points until the last minutes of his life and his eternal life in the hearts of the grateful people of Iran. As our old and beloved Khomeini said once: "The hostiles should know that Hashemi is alive because the movement is alive".

I therefore, announce 3 days of public mourning and a day of public holiday and express my sincerest condolences over the loss of the great national hero, Islamic intellectual and incomparable asset of the Islamic Republic of Iran to Imam Mahdi (AS), the Supreme Leader, great Maraji, scholars and clerics, prominent figures of the revolution and the state, the grateful Iranian nation, especially the noble people of Kerman province and Rafsanjan town, all his companions and followers, especially his respectful family, his patient wife and also his children and brothers, praying to the Almighty for the great man's mercy and highest places before Him, as well as sitting close to the Immaculate Imams (AS) and his companion, Imam Khomeini (RA), his comrades and martyrs of the Islamic Revolution and all people.

—Jan. 9, 2017, in a statement

Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif

The Revolution has lost a towering giant; the nation a dedicated patriot; the world an essential voice of reason. May he rest in peace.

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) January 9, 2017

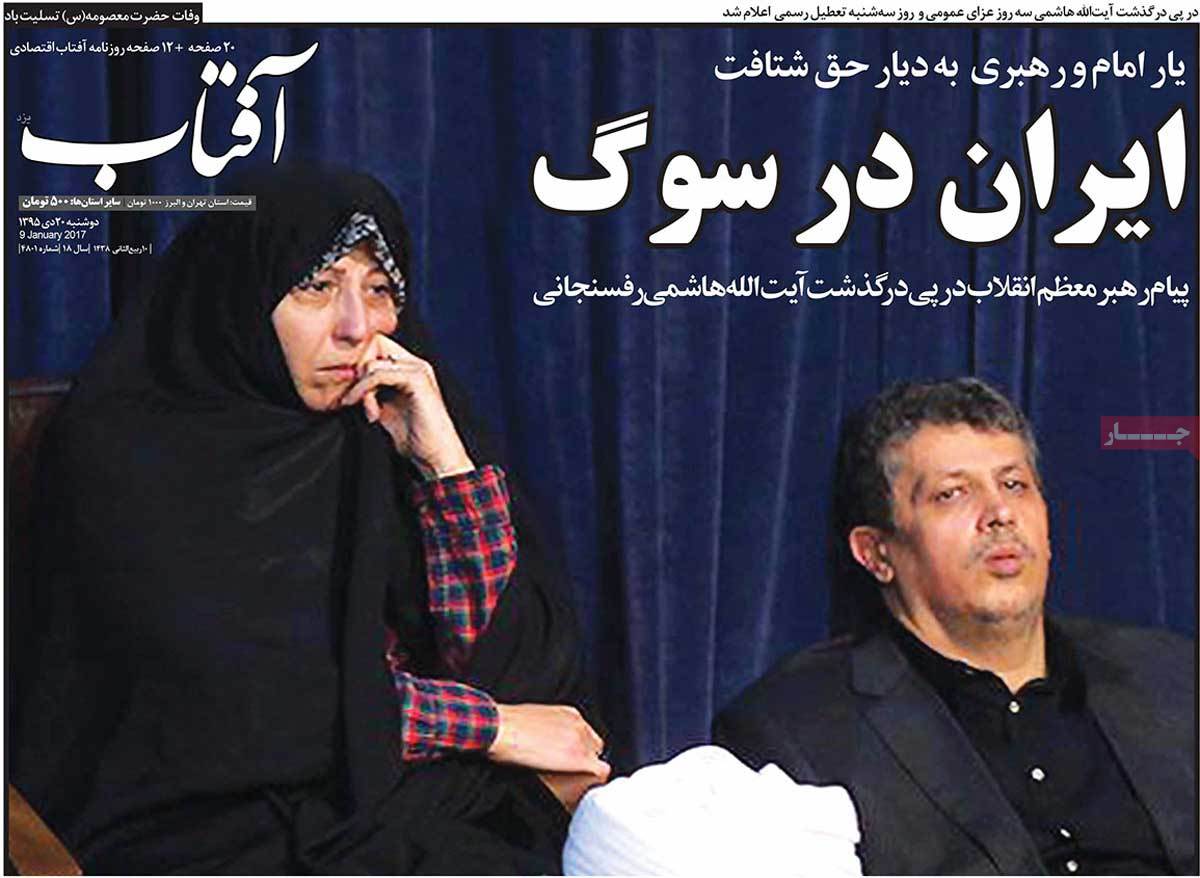

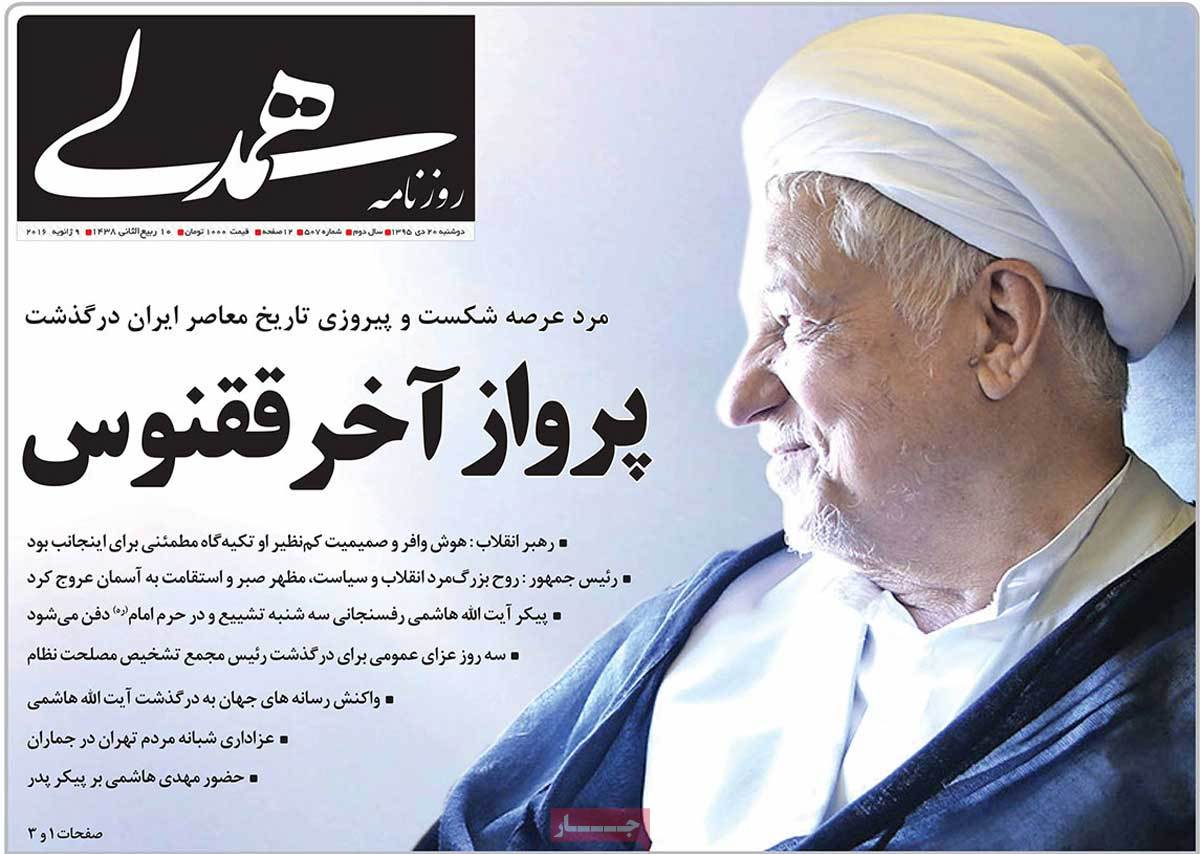

Newspaper Headlines

19 Dey

People’s Voice Is Silenced: Great Warrior, Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani, Passes Away

Haft-e Sobh

Goodbye General: 82 Years of Life, 60 Years of Struggle

Aftab-e Yazd

Iran in Grief: Companion of Imam Khomeini and Ayatollah Khamenei Passes Away

Hamdeli

Last Flight of Phoenix: Man of Losses and Victories in Iran’s Contemporary History Dies

Noavaran

Iran in Grief of Hashemi Rafsanjani

*Translations and graphics via Iran Front Page

Profile: Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

Rafsanjani was born in 1934 in Bahraman village near the south-central city of Rafsanjan, the district from which he gets his name. His father was a well-to-do pistachio farmer. Rafsanjani left home at age 14 to study Islamic jurisprudence in the holy city of Qom, where he developed a close relationship with Ayatollah Khomeini. In 1958, Rafsanjani married Effat Marashi, the daughter of a respected cleric. They had five children: Fatemeh, Mohsen, Faezeh, Mehdi and Yasser.

Rafsanjani joined the struggle against the Pahlavi dynasty in the late 1950s. He was detained seven times and imprisoned for a total of four years spread out between from 1958 to 1979, according to his bio.

Rafsanjani was a top adviser to Khomeini throughout the revolution. He was elected speaker of Iran’s first post-revolution parliament in 1980 and held the position for nine years.

Khomeini appointed Rafsanjani to be his personal representative on the Supreme Defense Council during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. He also briefly served as acting commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

Khomeini appointed Rafsanjani to be his personal representative on the Supreme Defense Council during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. He also briefly served as acting commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

But he also had enemies. In May 1979, he narrowly escaped assassination by members of the leftist Islamic group, Forqan.

For his wiliness, Rafsanjani was nicknamed “the shark,” which is also a play on his smooth beardless chin, a physical attribute inherited from Mongolian ancestors. He was also — somewhat cynically — nicknamed “Akbar Shah,” a dig at the king-like power he once wielded. His Cheshire cat grin was a staple of Iranian politics in the 1980s and 1990s — and a barometer of who and what was in favor.

Rafsanjani was inaugurated as president in July 1989, at a watershed moment. Khomeini had died in June and his lieutenants were now in charge. The Iran-Iraq War was over, permitting Tehran to begin the post-war reconstruction. After Khomeini’s death, the constitution was amended to eliminate the post of prime minister and vest his powers in the president. In the post-Khomeini period, Rafsanjani was the dominant figure in the two-man team of president and supreme leader that ran the Islamic Republic.

Rafsanjani attempted to move the country in a more pragmatic direction by ending Iran’s isolation. He launched economic liberalization, opening the state-dominated economy to domestic and foreign private sector investment. He placed technocrats in key posts. And he mollified women, the young and the middle class by easing social and cultural (but not political) controls.

He quietly resumed diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia, Morocco and Egypt. He in effect sided with the U.S.-led coalition to oust Iraq from Kuwait. And he helped win freedom for American hostages held by Lebanese allies.

He ushered in a controversial five-year development plan that envisaged foreign borrowing and greater private sector involvement. The government reduced exchange rates from seven to three, eased import and foreign currency restrictions, lifted price controls, and reduced state-subsidized goods from 17 to five. Hundreds of state-owned enterprises were slated for privatization.

The easing of social and cultural controls was evident in many spheres. Women could appear in public in brightly-colored scarves and show a bit of hair, nail-polish and lipstick. Young men and women could openly socialize on walks along the foothills of Tehran. The government tolerated a brisk underground trade in video-cassettes of Hollywood films. Previously banned satellite dishes allowed Iranians to tune in to CNN and “Baywatch.” Art galleries reopened.

Minister of Culture Mohammad Khatami adopted more liberal policies on film, theater, art, books and journals, such as Zanan, which addressed women’s issues. In literary and intellectual journals, such as Kiyan and Goftegu, a guarded but lively debate took place on civil society, the relationship between religion and democracy, and the balance between state authority and individual freedoms. The film industry flourished; Iranians won several international prizes.

Political restrictions remained, however. Several opposition leaders in exile were assassinated by Iranian agents. In 1994-1995, a number of intellectuals in Iran were found mysteriously dead on the streets or died in police custody. Rafsanjani never publicly condemned these killings. The political press remained closely controlled. Even centrist opposition parties, such as the Iran Liberation Front, were barely tolerated. The radical wing of clerics was excluded from 1990 elections for the Assembly of Experts, a body that chooses the supreme leader, and from 1992 parliamentary elections. But with the right-wing dominant, cultural liberalization ran into trouble. A conservative parliament purged Culture Minister Khatami in 1992, and Rafsanjani’s brother as the head of state radio and television two years later.

Supreme Leader Khamenei, gradually amassing power, campaigned against a Western “cultural onslaught.” Officially-sanctioned zealots attacked bookstores, cinemas and lectures by philosopher Abdolkarim Soroush, who argued for a tolerant, pluralistic Islam open to change and free of clerical domination. In 1993-1995, several journalists were sentenced to lashings or jail.

Other parts of Rafsanjani’s program also began to unravel. Excessive government spending and the easing of import and currency controls depleted foreign exchange reserves and led to inflation. Iran’s foreign debt rose. Severe retrenchment followed. In 1994-1995, imports were cut and private sector credit restricted. Foreign exchange controls, multiple exchange rates and price controls reappeared. Hardship led to riots in several towns in 1992 and again in 1994-1995.

Rafsanjani’s attempt to normalize foreign relations was hampered by Iran’s opposition to the Arab-Israeli peace process launched in Madrid in 1991 and support for Hezbollah, Lebanon’s radical Shiite movement. Iran objected to America’s large military presence in the Persian Gulf. Unable to purchase armaments from the West, Iran turned to China and Korea for short- and medium-range missiles and other weaponry. Washington was also disturbed by evidence Iran was pursuing a nuclear weapon. Iranian protégés were implicated in Buenos Aires bombings in 1992 and 1994 at the Israeli Embassy and a Jewish community center.

Rafsanjani’s attempt to normalize foreign relations was hampered by Iran’s opposition to the Arab-Israeli peace process launched in Madrid in 1991 and support for Hezbollah, Lebanon’s radical Shiite movement. Iran objected to America’s large military presence in the Persian Gulf. Unable to purchase armaments from the West, Iran turned to China and Korea for short- and medium-range missiles and other weaponry. Washington was also disturbed by evidence Iran was pursuing a nuclear weapon. Iranian protégés were implicated in Buenos Aires bombings in 1992 and 1994 at the Israeli Embassy and a Jewish community center.

Rafsanjani tried but failed to limit the damage done to Iran’s international relations by a death sentence issued by Ayatollah Khomeini against British writer Salman Rushdie, whose novel The Satanic Verses he considered offensive to Islam. In an attempt at an opening to the United States in March 1995, Rafsanjani signed a $1 billion agreement with the American oil company Conoco to develop Iranian offshore fields. But President Clinton killed the deal with an executive order that barred U.S. investment in Iran’s oil sector.

By the beginning of his second term, Rafsanjani had lost the initiative to the conservatives, now led by Khamenei. Rafsanjani left behind a legacy of pragmatism in domestic and foreign policy and also a political organization, the Executives of Construction, which would play a significant role in launching the reforms of the Khatami presidency. Launched by 16 of Rafsanjani’s cabinet ministers and high officials on the eve of the 1996 parliamentary elections, the group emphasized economic development and private sector entrepreneurship rather than ideology and revolutionary zeal. Along with allies, it won a bloc of 80 seats in the 270-member Majles and subsequently threw its electoral weight and skills behind the election campaign of Mohammad Khatami.

In 2013, Rafsanjani was barred from running for president, perhaps due to his outlook or to his advanced age. The Guardian Council did allow Rafsanjani to run for the Assembly of Experts, however. In February 2016, he led a slate of centrists and moderate conservatives in the Assembly of Experts election. He placed first in the race for 16 available seats in Tehran. Rafsanjani was widely believed to covet the job of supreme leader.

Rafsanjani and his family reportedly amassed significant wealth since the revolution. In 2003, Forbes named him as one of the “millionaire mullahs.” Critics have accused Rafsanjani and his sons of corruption. Rafsanjani’s oldest son Mohsen headed Tehran’s metro until he resigned in 2011. His youngest son Yasser, a businessman educated in Belgium, has run a successful export-import firm.

Rafsanjani’s middle son, Mehdi Hashemi, did well financially through connections to the oil industry. He used to head a subsidiary of the National Iranian Oil Company. He left Iran after the disputed 2009 elections for Britain. He was arrested on his return and jailed for three months for corruption and inciting unrest against the regime. Mehdi was released in December 2012. In 2015, however, he began serving a 10-year prison term after being convicted on three charges in separate cases involving national security, fraud and embezzlement.

Rafsanjani’s daughter Faezeh Hashemi, a former Member of Parliament and vice president of Iran’s Olympic committee, was charged with “spreading propaganda” after the disputed 2009 presidential election. She spent six months in prison; she was released in March 2013.

In 2016, the Guardian Council disqualified two of Rafsanjani’s children from running for parliament. Fatemeh Hashemi had been outspoken in her criticism of President Ahmadinejad’s economic mismanagement. Mohsen Hashemi, who had served on Tehran’s city council,was also barred from running. Both had reformist views.

*Information on Rafsanjani’s presidency from Shaul Bakhash’s chapter on Iran’s presidents in The Iran Prime with other information from previous articles by Robin Wright and Garrett Nada