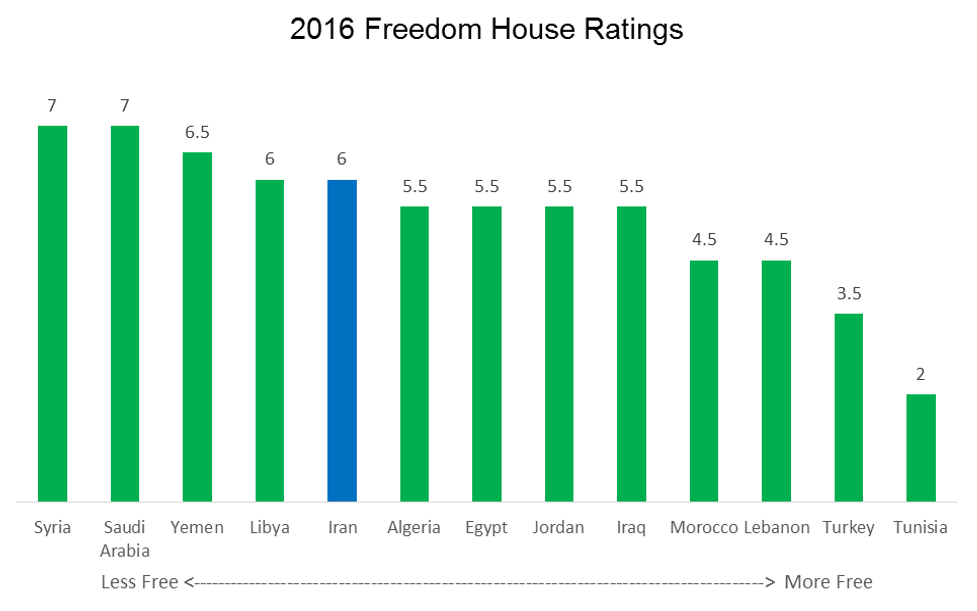

Elections in the Islamic Republic are colorful, complicated affairs that can produce unexpected results, occasionally even turning the political tide. Ultimate authority in the theocracy still rests with the supreme leader, and candidates are heavily vetted by the Guardian Council of twelve unelected Islamic jurists. But Iranian politics do have democratic elements that get higher marks than the elections in key Arab countries, including Syria, a close ally, and Saudi Arabia, its arch rival. Iran falls only slightly below the polling process in Jordan, Egypt, Iraq and Algeria. By international standards, however, it falls short of elections held in Tunisia, Morocco and Turkey. The following is a breakdown of electoral systems in Iran compared to other Middle Eastern countries.

Iran

Freedom House Rating: Not Free, 6

Electoral System: Theocratic republic

Iranian politics center around formal parties, unofficial political factions, and coalitions that

range from reformist to hardline. Iran’s constitution promises direct elections for the parliament, presidency, and Assembly of Experts. Campaigns are brief, usually counted in mere days, but vibrant. Since the 1979 revolution, the pendulum has swung between right and left--and back again—after elections. Presidents have had disparate agendas. Debates in parliament can be feisty.

Yet political dialogue and dissent have significant limits. All candidates must swear absolute adherence to the principals of the Islamic Republic and the authority of the supreme leader. Rivalries among the revolutionary factions have been intense and even heated. Over the decades, the regime has turned on many of its own who have proposed change: A former prime minister and a speaker of parliament have spent years under house arrest. Former members of parliament and a vice president have been sentenced to prison terms. Incumbent members of parliament and a former president have been disqualified from running again for office. Some have even been banned from traveling. Thousands of candidates have been refused the right to run for office. Women have been repeatedly disqualified for running for the presidency and the Assembly of Experts, or to have positions in either the judiciary or Guardian Council.

Freedom House classifies Iran as “Not Free” as there have been “no significant improvements in the human rights situation” and “hard-liners [remain] in control of key state institutions…determined to prevent any attempts at reform.” The

State Department identifies “severe restrictions on civil liberties, including the freedoms of assembly, speech, religion, and press; limitations on the citizens’ ability to change the government peacefully through free and fair elections."

Political structure: The supreme leader is Iran’s

most powerful official, with direct or indirect power over all three branches of government (executive, legislative, and judicial). He has the final say over all major domestic or foreign policy decisions. The president is elected; he is limited to two consecutive terms with the option of an additional nonconsecutive term. The president’s role, while limited by the supreme leader’s authority, has

grown since the constitution was amended in 1989. Iran has a unicameral parliament with 290 members that serve four-year terms. The Majles, or parliament, has various

responsibilities including drafting legislation, ratifying international treaties, and approving the annual budget. It is a weak institution compared to the other branches of government, especially since the Guardian Council must review and approve any law passed by the Majles for Islamic and constitutional adherence. All political candidates are vetted by the Guardian Council, 12 Islamic jurists appointed by the supreme leader.

Last election: The last presidential election was held on June 14, 2013. Hassan Rouhani, a centrist candidate, won the election with 51 percent of the vote. He ran against seven other candidates;

686 candidates were rejected by the Guardian Council. It was the first presidential election to be held after

Green Movement demonstrations challenged Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s 2009 reelection. At the height of the movement, 3 million peaceful protestors demonstrated in the streets against the results of the election. The next presidential election is slated for 2017.

In the 2012 parliamentary election, conservatives and hardliners won the majority of seats, partly due to the limited number of approved reformist candidates. For the 2016 poll, a record 12,123 candidates registered to run, but

over half were disqualified by the Guardian Council. Following an appeals process, the Guardian Council approved an additional 1,500 candidates. The finalized list includes 6,229 candidates, or about 51% of those who initially registered.

Tunisia

Freedom House Rating: Free, 2

Electoral System: Republic

Tunisia is often hailed as the lone Arab Spring success, but the fragile transition has been tainted by failure to address economic woes that sparked the 2011 uprising as well as by indigenous and regional extremism.

After the Jasmine Revolution ousted President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, autocracy was replaced by

five disparate parties ranging from Islamists to groups aligned with the ancien regime. Ennahda, Tunisia’s leading Islamist party, won a plurality of seats in the 2011 parliamentary elections and formed a coalition government with two secular parties. After the assassination of two opposition leaders in 2013, the coalition resigned and handed over power to a technocratic government to oversee elections. It was the first time Tunisia has

peacefully transferred power from one party to another, a rarity in the Arab world.

In January 2014, the National Constituent Assembly – which included the major parties and involved a nation-wide consultative process – wrote a new constitution that guarantees individual rights. A new parliament and president were elected in late 2014. Parliament even

rejected a proposal to exclude Ben Ali era officials from politics, leading to a more inclusive election process. Freedom House

upgraded Tunisia to “Free” status in 2015 due to “the adoption of a progressive constitution, governance improvements under a consensus-based caretaker administration, and the holding of free and fair parliamentary and presidential elections, all with a high degree of transparency.” In 2015, the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Yet Tunisia has been increasingly divided over the new order. Islamists and secularists have clashed over economic policy, security issues, and human rights. Poverty, unemployment, and lack of investment generated growing marginalization, particularly in rural areas with unequal access to government services. Radicalization among the young led to bursts of violence, including two of the deadliest acts of terrorism, in 2015. Thousands of young Tunisians also flocked to conflict zones, particularly Iraq and Syria, to join jihadist groups. The

State Department has documented ongoing problems, such as human rights violations by security forces and violence against journalists.

Political structure: The president, who is head of state, is directly elected to a five-year term. The prime minister, who is head of government, is selected by the majority party and then appointed by the president. A unicameral parliament, has 217 seats; members serve five-year terms. Tunisia had a bicameral legislature under former President Ben Ali, established via a constitutional referendum in 2002.

Last election: Beji Caid Essebsi won the presidency with 56 percent of the vote in the final runoff election, and his secular party Nidaa Tounes won the most seats in a separate parliamentary election. But Nidaa Tounes’ parliamentary bloc began to fracture in late 2015, and 22 MPs from Nidaa Tounes split from the party to form the

Al Horra bloc in January 2016. As a result, Ennahda once again became the largest party in parliament. The next elections are scheduled for 2019.

Turkey

Freedom House Rating: Partly Free, 3.5

Electoral System: Republican parliamentary democracy

After the Arab Spring in 2011, Turkey was briefly cited as a model—in balancing Islam and democracy--for an Arab world in transition. But Freedom House downgraded Turkey’s freedom rating to “Partly Free” in 2016, partly because of “intense harassment of opposition members and media outlets by the government and its supporters” before parliamentary elections in late 2015. A week before the poll, government forces seized the assets of major newspapers and television channels that had been critical of the ruling party.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) was popular during its first dozen years in power, as it oversaw unprecedented economic growth and began ascension talks with the European Union. It has been particularly successful with forming coalitions in parliament. The June 2015 election, however, was the first blow to the AKP’s grip on power in 13 years after it failed to win an outright majority. It regained the majority at second vote in November.

Turkey’s multiparty system is inhibited by a 10 percent vote threshold for parliamentary representation – a significantly higher bar than Western parliamentary democracies, such as Germany (5 percent) or Denmark (2 percent). It gives larger parties an advantage. Parties can also be disbanded by the courts if they are in violation of the constitution. In the past, this has affected Kurdish and Islamist parties.

As of early 2016, President Erdogan effectively controlled decision-making, with the AKP in control of the presidency and parliament. He has advocated constitutional changes that would bestow more authority to an executive presidency. But the AKP is 14 seats short of the number needed to alter the constitution without a referendum.

Political structure: Turkey’s head of state is the president, elected to a five-year term and eligible for a second term. The prime minister, the head of government, is appointed by the president from among members of parliament. The parliament, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, has 550 members elected to four-year terms.

Last election: Turkey held its first direct presidential election in 2014 after a constitutional referendum in 2007 changed the election process. Previously, presidents were elected by parliament. The referendum was introduced by Erdogan, then the Prime Minister. He won the presidential election with almost 52 percent of the vote.

Turkey held two parliamentary elections in 2015. The parliamentary election in June was unable to form a coalition government, resulting in a second election in November when President Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party won 317 seats, securing a majority in parliament.

Lebanon

Freedom House Rating: Partly Free, 4.5

Electoral System: Republic

After independence from France, Lebanon was the most democratic of the 22 nations in the Arab world, but its fragile political system is vulnerable to the tensions among its 18 religious sects. An unwritten national pact divides political positions proportionately between Christians and Muslims, a complex formula further complicated by the fact Lebanon has not held a national census since 1932. Rivalries over the distribution of power spawned a 15-year civil war, between 1975 and 1990, and has sparked repeated political crises ever since. In 2014, Lebanon embarked on a prolonged stalemate over the presidency. By early 2016, Parliament had held

32 polls to elect a new president—and repeatedly failed.

Lebanese parties are notoriously – and sometimes oddly – fluid in their alignments and loyalties. Lebanese politics are also defined by regional ties. In 2016, the two largest coalitions in parliament were: The March 8 Movement, which included Hezbollah, a Shiite party, and the right-wing Free Patriotic Movement of former General Michel Aoun, a Maronite Christian. It has supported the Syrian regime of President Bashar Assad. The March 14 Alliance is led by Saad Hariri, son of former Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri, a Sunni Muslim who was assassinated in 2005, and includes Amin Gemayel, a former president and a Maronite Christian. It is deeply opposed to the Assad regime in Syria.

Political deadlock led

Freedom House to downgrade Lebanon to “Partly Free” in 2015 due to “the parliament’s repeated failure to elect a president and its postponement of overdue legislative elections for another two and a half years, which left the country with a presidential void and a National Assembly whose mandate expired in 2013.”

Political structure: Lebanon’s government is designed to distribute power among its 18 religious sects. The unwritten National Pact, agreed upon in 1943, stipulated that the president must be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim, the parliamentary speaker a Shiite Muslim, and the deputy prime minister and deputy speaker of parliament must be Eastern Orthodox Christians. The Taif Accords, the agreement ending the Lebanese Civil War in 1989, reallocated some of these responsibilities to lessen the power given to Maronite Christians during French rule. Under this agreement, the prime minister is no longer responsible to the president, but rather to parliament.

The president is elected by the National Assembly, or parliament, for a six-year term and is eligible for additional nonconsecutive terms. The prime minister and deputy prime minister, in turn, are appointed by the president for four-year terms, based partly on their electoral performance or strength of their coalition. The National Assembly is unicameral, and is made up of 128 members elected to four-year terms.

Latest Election: Lebanon has not held parliamentary elections since 2009. Elections were initially slated for June 2013, but were

postponed twice by parliament. The delay has been due partly to the escalating conflict in neighboring Syria as well as domestic disagreements over political support for Syrian President Bashar al Assad’s regime.

Morocco

Freedom House Status and Rating: Partly Free, 4.5

Electoral System: Constitutional monarchy

Since independence from France in 1956, political life in Morocco has been dominated by an absolute monarch who tolerates elections but not all opposition. After protests in 2011 – dubbed the February 20 movement –King Mohammed VI enacted limited constitutional reforms and ran elections in 2011 that the

State Department deemed “credible and relatively free from irregularities.” The Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD) won a plurality of seats in parliament, while 17 other parties also secured seats. But the king still has virtually unlimited

authority to issue decrees, appoint cabinet members, dissolve parliament, command the armed forces, and oversee the judicial system. The PJD, despite holding the largest parliamentary bloc, has prioritized staying in power over pursuing meaningful reforms. Five years after the February 20 movement, Morocco’s political reforms have failed to meet the movement’s original demands for an “empowered parliament” and a “

king who reigns but does not rule.”

In 2016,

Freedom House downgraded Morocco’s freedom rating to “Partly Free” due to “the government’s repression of dissent, including disruption of meetings, assaults on activist leaders, and the imposition of long prison sentences on journalists and civil society figures.” The

State Department has pointed out “the lack of citizens’ ability to change the constitutional provisions establishing the country’s monarchical form of government, corruption in all branches of government, and widespread disregard for the rule of law by security forces,” as human rights violations.

Political structure: King Mohammed IV has been the monarch of Morocco since 1999. The bicameral

parliament consists of the Chamber of Counselors (90-120 seats) and the Chamber of Representatives (395 seats), elected for six and five year terms, respectively. The prime minister is appointed by the king from the largest party in parliament.

Latest Election: The king’s political reforms included

changes to the constitution which allowed for an elected government that could appoint ministers and must be consulted before the king can dissolve parliament.The last Chamber of Representatives election was held on Nov. 25, 2011; the body’s next election is scheduled for Oct.7, 2016.

Iraq

Freedom House Status and Rating: Not Free, 5.5

Electoral System: Parliamentary democracy

Iraqi democracy has been fragile ever since the fall of Saddam Hussein, which unleashed long-suppressed ethnic, sectarian and tribal rivalries. The rise of al Qaeda after the 2003 U.S. invasion and the 2014 conquest of a third of Iraqi territory by Islamic State exacerbated tensions. A series of democratically elected governments since 2003 have had difficulty establishing their legitimacy, largely because they failed to address the twin issues of sharing political power and oil revenues. Parliamentary elections in 2014 reflected widespread discontent within the minority Sunni minority, partly spurred by government crackdowns on Sunni protest camps in 2013. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was also

accused of corruption, “mismanagement of security…and an improper concentration of power in the prime minister’s office.”

Despite these troubles, Freedom House improved Iraq’s political rights rating in 2016, from 6 to 5. This is due to “a parliamentary vote that withdrew the prime minister’s mandate to make unilateral reforms to the government, reasserting the parliament’s constitutional powers in a political system that had become skewed toward the executive in recent years.” Iraq remains “Not Free” however, according to Freedom House.

Political structure: Iraq has a president as the head of state and a prime minister as the head of government. The former is elected by the parliament to serve a four-year term and is eligible for a second term. The latter is nominated by the president and subsequently approved by the parliament. Most executive power lies with the prime minister. The unicameral parliament, the Council of Representatives, has 328 members who serve four-year terms. While the constitution calls for a bicameral parliament (the creation of an upper house of parliament in addition to the Council), this has not yet been implemented.

Latest Election: Despite ongoing conflict in Iraq, the 2014 parliamentary elections were considered a success. Based on the results, it appeared that Nouri al Maliki, who had already served for two terms as prime minister, would be appointed to the position again. His State of Law coalition, a Shiite group, won 92 seats in parliament, making it the largest voting bloc. His nomination, however, was met with

resistance both domestically and internationally, especially after the ISIS takeover of Mosul and other Iraqi territory. Ultimately, the State of Law coalition withdrew their support for al Maliki and appointed Haidar al Abadi as prime minister.

Jordan

Freedom House Status and Rating: Not Free, 5.5

Electoral System: Constitutional monarchy

Jordan has been a constitutional monarchy since 1952. The concentration of executive power in the crown and the monarchy’s dependence on loyalist tribes has allowed corruption and nepotism to become entrenched in politics. Jordan’s political spectrum reflects divisions between Palestinians and East Bankers, Islamists and non-Islamists, and rival tribes. Political parties, which were legalized in 1992, are relatively weak in the tribal-centric system. East Bankers from loyalist tribes tend to dominate the security forces and the government while Palestinians are underrepresented.

For decades, the tense political situation has been colored by regional conflicts, starting with the Arab-Israeli conflict. Jordan is home to more than two million Palestinian refugees. The conflicts in Iraq and Syria have also created challenges for the country. By the end of 2015, at least 57,000 Iraqi

refugees were living in Jordan. The Syrian civil conflict added at least another 620,000 “persons of concern” in the country, according to the UN Refugee Agency. The influx of refugees has put pressure on the national budget and public services.

The rise of ISIS in neighboring Iraq and Syria has led to some 1,800 Jordanians leaving to join the group, and those who return face antiterrorism charges. Anti-terrorism laws have also been expanded in ways which

Human Rights Watch claims “threaten[s] freedom of expression.”

Jordan’s monarchy allows for some political participation, despite restrictions on freedom of expression. The Public Gatherings Law, enacted in 2011, allows for Jordanians to hold public meetings and gatherings without requiring government permission. Parliamentary elections were held in 2013, but “international observers noted instances of vote buying and criticized the electoral laws as unfair. Political campaigning was seen as noncompetitive and relatively absent in wide areas of the country due to the overall influence of tribal affiliations, a lack of financing, and boycotting by opposition groups,” according to

Freedom House.

Political Structure: Jordan is led by the Hashemite royal family, headed by King Abdullah II since 1999. The bicameral parliament, known as the National Assembly, consists of the Senate (or House of Notables; 60 seats) and Chamber of Deputies (or House of Representatives; 150 seats). The prime minister and members of the Senate are appointed by the monarch for four-year terms. Members of the Chamber of Deputies are elected to four-year terms. The monarch has the power to dissolve parliament and fire prime ministers. King Abdullah most recently

dissolved parliament in 2012, and has fired four prime ministers in the past.

Latest Election: Jordan most recently held parliamentary elections in January 2013. This was the first election to be overseen by the Independent Election Commission (IEC), as opposed to the Ministry of Interior. The IEC was created by political reforms to guarantee an autonomous supervisory body for parliamentary elections. The majority of candidates were independents, not affiliated with specific lists. Some opposition groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood’s political wing, the Islamic Action Front,

boycotted the election citing insufficient political reforms.

Egypt

Freedom House Status and Rating: Not Free, 5.5

Electoral System: Republic

Since the 1952 ouster of the monarchy, Egypt has been led by former generals, with the exception of a brief experiment in democracy. Egypt’s political system has recently become even more authoritarian, despite high expectations for democracy after longtime President Hosni Mubarak was ousted in 2011. Capitalizing on new political openings, Islamists won a majority of parliamentary seats in 2011, and Mohamed Morsi was elected president in 2012. He was ousted by military coup after only one year in office. In 2014, Abdel Fattah al Sisi – a former general who led the coup against Morsi – was elected president. Observers noted “major flaws” in the election process, according to

Freedom House. The election was also marred by low voter turnout, irregularities in the use of state resources, and voter intimidation.

The political climate for opposition groups has become increasingly toxic. “Authorities have effectively banned protests, imprisoned tens of thousands—often after unfair trials—and outlawed the country’s largest opposition group, the Muslim Brotherhood,” according to

Human Rights Watch, The regime has assumed broad powers under counterterrorism law, mistreated detainees, and prosecuted independent NGOs and journalists.

Freedom House downgraded Egypt’s rating in 2015 due to the “complete marginalization of the opposition, state surveillance of electronic communications, public exhortations to report critics of the government to the authorities, and the mass trials and unjustified imprisonment of members of the Muslim Brotherhood.” The regime has assumed broad powers under counterterrorism law, mistreated detainees, and prosecuted independent NGOs and journalists.

Political Structure: After President Hosni Mubarak stepped down in 2011, the Egyptian constitution was suspended and parliament was disbanded. The military presented a plan to draft a new constitution and hold parliamentary and presidential elections, but silenced protests demanding that the process happen more quickly. In the 2011-2012 elections, Islamist parties won about 70 percent of the seats in the lower house of parliament. Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood leader, became Egypt’s first democratically elected president in 2012 before his ouster by a military coup in July 2013.

Egypt’s president is the head of state and the prime minister is the head of government. The president is elected to four-year terms; the prime minister is appointed by the president. The unicameral parliament is called the House of Representatives (no less than 450 seats) and members serve for five-year terms. The president has the power to dissolve parliament.

Latest Election: General Sisi won the 2014 presidential election with 96 percent of the vote, according to officials. During the election,

Freedom House reported that “observers noted major flaws in the process.” Sisi’s election was also characterized by low voter turnout, irregularities such as the use of state resources to support him, and voter intimidation.

The most recent parliamentary elections were held in 2015, three years after the previous parliament had been dissolved in June 2012. The Free Egyptians party won the most seats, but still only comprise 11 percent of parliament. The majority of members do not belong to any party. Egypt finally held new parliamentary elections in 2015, but voter turnout was again low, and many opposition parties boycotted the poll.

Algeria

Freedom House Status and Rating: Not Free, 5.5

Electoral System: Republic

The military looms as the ultimate arbiter of Algeria’s political process. After winning its independence from France in 1962, Algeria became a one-party system dominated by the National Liberation Front (FLN). A ban on political parties was lifted in 1988, and more than 50 parties competed in 1992 elections, among them the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). But when the FIS, an Islamist party, won the first round of parliamentary elections, the military led a coup against the president, nullified the results, banned FIS and arrested its leadership—a sequence that spawned a decade-long civil war and more than 100,000 deaths.

In 2011, small-scale Arab Spring protests failed to gain much momentum in Algeria, where people were wary of unrest after years of conflict. The government did undertake some modest reforms. The Ministry of Interior, which must approve all political parties, authorized 23 new parties to compete in the 2012 parliamentary elections. FIS was still not permitted to participate in politics, though smaller Islamist parties – running under the banner of the Green Algeria Coalition – were allowed to run and hold seats in parliament.

Despite regular presidential and parliamentary elections, Algeria has very little political space for opposition parties. President Abdelaziz Bouteflika was reelected to a fourth term in 2014, after constitutional amendments in 2008 eliminated the two-term limit that would have prevented his reelection. The 2014 election’s runner up, Ali Benflis, declared “

fraud on a massive scale” following Bouteflika’s win. According to the 2014 State Department

Human Rights Report, “Foreign observers characterized the [2014] elections as largely peaceful but noted low voter turnout and a high rate of ballot invalidity.”

The president has since proposed constitutional reforms that would return the presidency to a two-term limit after he steps down. Bouteflika has suffered two strokes in recent years, and notable Algerian figures have voiced

doubts about whether he continues to make decisions or if he has been quietly replaced by others in the political or military elite. These figures include Lakhdar Bouregaa, a prominent former fighter of Algeria’s independence war, who admitted, “We have this feeling that the president has been taken hostage by his direct entourage.”

Political Structure: Algeria is led by the president, the head of state, and the prime minister, the head of government. The president is directly elected and serves five-year terms with no term limits. The prime minister is appointed by the president. The bicameral legislature consists of the Council of the Nation (144 seats) and the National People’s Assembly (489 seats) with members serving five-year terms.

Latest Election: The National Liberation Front, President Bouteflika’s party, trounced opposition parties in the most recent parliamentary election in 2012, winning 208 out of 462 seats. Islamist parties had

hoped to significantly increase their number of seats following the Arab Spring uprisings, but failed to do so.President Abdelaziz Bouteflika was reelected to a fourth term with 82 percent of the vote in the 2014 presidential election.

Libya

Freedom House Status and Rating: Not Free, 6

Electoral System: Transitional government

Libya’s political life has been dominated by armed factions vying for power – including the Islamic State – since the 2011 revolution that overthrew Muammar Qaddafi. Even before the revolution, political life was largely stifled. Qaddafi, who came to power in 1969, suppressed political parties, civil society, and the private sector. Local and tribal affiliations were often stronger than political identities.

Qaddafi left behind a power vacuum that was filled by a host of locally affiliated militias. A transitional government was formed in 2012, but political infighting derailed Libya’s democratic transition. More than 100 political parties or lists participated in the 2012 General National Congress (GNC) elections, although “the legitimacy and integrity of the new parties steadily eroded, and all candidates in the 2014 elections were required to run as independents,” according to Freedom House.

In 2014, Libyans elected a Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution and a House of Representatives (HoR) to replace the General National Congress (GNC), the interim legislature. After the election, however, political opponents of the HoR

denied the legitimacy of the elections and established a rival GNC in Tripoli. Libya split into two rival governments: the GNC, dominated by Islamists, and the House of Representatives (HoR) dominated by secular politicians. In December 2015, the United Nations finalized a plan for a unity government. But by February 2016, there had been repeated delays in implementing the agreement.

Freedom House downgraded Libya’s status to “Not Free” due to its “descent into a civil war, which contributed to a humanitarian crisis as citizens fled embattled cities, and led to pressure on civil society and media outlets amid the increased political polarization.”

Political Structure: The head of state in Libya is the Speaker of the House of Representatives (the parliament), while the head of government is the prime minister. The House of Representatives elects both positions. The unicameral parliament has 200 seats.

Latest Election: Libya has not held an election – or had a unified government – since the 2014 election that led to the split between the GNC and HoR.

Yemen

Freedom House Status and Rating: Not Free, 6.5

Electoral System: Republic

Yemen has been in a state of political and humanitarian crisis ever since its Arab Spring protests began in 2011. In the uprisings, Yemenis called for the ouster of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had been in power for 33 years. Protests spread even though President Saleh agreed not to seek reelection, and crackdowns by security forces left hundreds dead. Initially, Saleh refused to sign a Gulf Cooperation Council brokered deal that would have ended his rule, but finally signed it in November 2011. He was replaced by his deputy in 2012, and a civil war began in 2014 between Houthi rebels from northern Yemen and those loyal to the existing government. The Houthis are a large clan of Zaydi Shiites who had been politically marginalized for decades.

Freedom House dropped Yemen’s rating from 6 to 7 in 2016, due to “the collapse of the political system and the effects of an escalating civil war and related Saudi-led military intervention on the civilian population.”

Despite Saleh’s decades-long reign, Yemen had well-developed opposition groups. According to

Freedom House, they “have historically been able to wring some concessions from the government. The 2011 ouster of Saleh was accomplished through a sustained campaign of protests motivated primarily by frustration with imbalances of power and high levels of corruption, but also by lack of access to decision-making and political participation by regular citizens.”

Political Structure: The president is the head of state and is elected to seven-year terms. The prime minister is the head of government and is appointed by the president.

The bicameral parliament consists of the Shura Council (111 seats) and the House of Representatives (301 seats). The president appoints members of the former. Members of the latter are elected to six-year terms.

Latest Election: After President Saleh’s ouster, Vice President Abd Rabuh Mansur Hadi became president in an uncontested vote. Hadi fled the capital, Sanaa, under pressure from Houthi forces and resigned from the presidency in January 2015. He withdrew his resignation a month later after escaping to Aden, then to Saudi Arabia, and finally returning to Aden in September 2015.

Saudi Arabia

Freedom House Status and Rating: Not Free, 7

Electoral System: Monarchy

The Saudi royal family dominates almost every aspect of political life in Saudi Arabia. The ruling family has strong links to the ultra-conservative Wahhabi branch of Sunni Islam dating back to the 18

th century.

Clerics do not play a formal role in government, but they have been incorporated into the political establishment through the Senior Council of Ulama, the kingdom’s highest religious body. The council advises the king and provides endorsements for state policies. In 2009, the king

extended membership for the first time to non-Wahhabi scholars.

Organized political dissent is virtually nonexistent within Saudi Arabia, and the monarchy keeps a tight grip on its power. Punishments for speaking against the political system are harsh, and numerous political activists have been imprisoned for their criticisms. The Muslim Brotherhood and Hezbollah – both popular organizations domestically and potential threats to the monarchy – were classified by the regime as terrorist groups in 2014.

The

State Department cited “citizens’ lack of the ability and legal means to change their government; pervasive restrictions on universal rights such as freedom of expression, including on the internet, and freedom of assembly, association, movement, and religion; and a lack of equal rights for women, children, and noncitizen workers,” as human rights concerns in 2014.

Freedom House classifies Saudi Arabia as “Not Free” because of the kingdom’s strict restrictions on free speech and dissent.

Political Structure: Saudi Arabia is ruled by the al Saud family, headed by King Salman bin Abd al Aziz Al Saud since January 2015. He acts as prime minister of the Consultative Council as well, and is therefore both the head of state and head of government.

The Consultative Council, or Majles al Shura, consists of 150 members appointed by the monarch to four-year terms. It has limited legislative powers. The king recently appointed 30 women to the Council in 2013. Political parties are not allowed.

Latest Election: Saudis can vote in municipal elections, which create advisory councils at the municipal level. These elections were

introduced in 2005, and have occurred twice since then (in 2011 and 2015). Women were able to run and vote for the first time in the 2015 elections. They won about one percent of available seats.

Syria

Freedom House Status and Rating: Not Free, 7

Electoral System: Republic under an authoritarian regime

Since independence from France, Syria has had a long history of instability, coups and wars, with elections that never had credibility. During 45 years under the Assad dynasty, Syria became one of the most authoritarian and brutal regimes in the Middle East. The protest movement spawned by the Arab Spring in 2011 was the largest in its modern history, but it quickly spiraled into civil war. It now involves pro-government forces, dozens of anti-Assad rebel groups with disparate interests, and extremist jihadis in ISIS and al Nusra Front. Regional intervention by rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as various levels of global intervention by the United States and Russia, have further complicated the matter. Presidential elections were held in 2014, but they were widely criticized by democratic countries as

illegitimate since it was held in government-controlled areas during an ongoing civil war.

Freedom House classified Syria as “Not Free” in 2015, citing “worsening religious persecution, weakening of civil society groups and rule of law, and the large-scale starvation and torture of civilians and detainees.”

Political Structure: The Syrian president is elected to seven-year terms and is eligible for a second term. The president appoints the prime minister and deputies. The presidential electoral system was enacted in 2012, whereas in the past a sole candidate was nominated by the ruling Baa’th Party. President Hafez al Assad held the office from 1971 until his death in 2000. His son, Bashar, ran unopposed for president, and he has held the position since then.

The unicameral parliament, the People’s Council, consists of 250 members serving four-year terms. It holds very limited independent legislative power. Most of the political power is in the hands of the executive branch.

Latest Election: President Bashar al Assad won about 89 percent of the vote in the 2014 presidential election.

Katayoun Kishi is a research assistant at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Cameron Glenn, a senior program assistant at the U.S. Institute of Peace, and Garrett Nada, Assistant Editor of The Iran Primer, contributed to these profiles.

Iranian politics center around formal parties, unofficial political factions, and coalitions that range from reformist to hardline. Iran’s constitution promises direct elections for the parliament, presidency, and Assembly of Experts. Campaigns are brief, usually counted in mere days, but vibrant. Since the 1979 revolution, the pendulum has swung between right and left--and back again—after elections. Presidents have had disparate agendas. Debates in parliament can be feisty.

Iranian politics center around formal parties, unofficial political factions, and coalitions that range from reformist to hardline. Iran’s constitution promises direct elections for the parliament, presidency, and Assembly of Experts. Campaigns are brief, usually counted in mere days, but vibrant. Since the 1979 revolution, the pendulum has swung between right and left--and back again—after elections. Presidents have had disparate agendas. Debates in parliament can be feisty. Tunisia is often hailed as the lone Arab Spring success, but the fragile transition has been tainted by failure to address economic woes that sparked the 2011 uprising as well as by indigenous and regional extremism. After the Jasmine Revolution ousted President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, autocracy was replaced by five disparate parties ranging from Islamists to groups aligned with the ancien regime. Ennahda, Tunisia’s leading Islamist party, won a plurality of seats in the 2011 parliamentary elections and formed a coalition government with two secular parties. After the assassination of two opposition leaders in 2013, the coalition resigned and handed over power to a technocratic government to oversee elections. It was the first time Tunisia has peacefully transferred power from one party to another, a rarity in the Arab world.

Tunisia is often hailed as the lone Arab Spring success, but the fragile transition has been tainted by failure to address economic woes that sparked the 2011 uprising as well as by indigenous and regional extremism. After the Jasmine Revolution ousted President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, autocracy was replaced by five disparate parties ranging from Islamists to groups aligned with the ancien regime. Ennahda, Tunisia’s leading Islamist party, won a plurality of seats in the 2011 parliamentary elections and formed a coalition government with two secular parties. After the assassination of two opposition leaders in 2013, the coalition resigned and handed over power to a technocratic government to oversee elections. It was the first time Tunisia has peacefully transferred power from one party to another, a rarity in the Arab world. After the Arab Spring in 2011, Turkey was briefly cited as a model—in balancing Islam and democracy--for an Arab world in transition. But Freedom House downgraded Turkey’s freedom rating to “Partly Free” in 2016, partly because of “intense harassment of opposition members and media outlets by the government and its supporters” before parliamentary elections in late 2015. A week before the poll, government forces seized the assets of major newspapers and television channels that had been critical of the ruling party.

After the Arab Spring in 2011, Turkey was briefly cited as a model—in balancing Islam and democracy--for an Arab world in transition. But Freedom House downgraded Turkey’s freedom rating to “Partly Free” in 2016, partly because of “intense harassment of opposition members and media outlets by the government and its supporters” before parliamentary elections in late 2015. A week before the poll, government forces seized the assets of major newspapers and television channels that had been critical of the ruling party. After independence from France, Lebanon was the most democratic of the 22 nations in the Arab world, but its fragile political system is vulnerable to the tensions among its 18 religious sects. An unwritten national pact divides political positions proportionately between Christians and Muslims, a complex formula further complicated by the fact Lebanon has not held a national census since 1932. Rivalries over the distribution of power spawned a 15-year civil war, between 1975 and 1990, and has sparked repeated political crises ever since. In 2014, Lebanon embarked on a prolonged stalemate over the presidency. By early 2016, Parliament had held 32 polls to elect a new president—and repeatedly failed.

After independence from France, Lebanon was the most democratic of the 22 nations in the Arab world, but its fragile political system is vulnerable to the tensions among its 18 religious sects. An unwritten national pact divides political positions proportionately between Christians and Muslims, a complex formula further complicated by the fact Lebanon has not held a national census since 1932. Rivalries over the distribution of power spawned a 15-year civil war, between 1975 and 1990, and has sparked repeated political crises ever since. In 2014, Lebanon embarked on a prolonged stalemate over the presidency. By early 2016, Parliament had held 32 polls to elect a new president—and repeatedly failed. Since independence from France in 1956, political life in Morocco has been dominated by an absolute monarch who tolerates elections but not all opposition. After protests in 2011 – dubbed the February 20 movement –King Mohammed VI enacted limited constitutional reforms and ran elections in 2011 that the State Department deemed “credible and relatively free from irregularities.” The Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD) won a plurality of seats in parliament, while 17 other parties also secured seats. But the king still has virtually unlimited authority to issue decrees, appoint cabinet members, dissolve parliament, command the armed forces, and oversee the judicial system. The PJD, despite holding the largest parliamentary bloc, has prioritized staying in power over pursuing meaningful reforms. Five years after the February 20 movement, Morocco’s political reforms have failed to meet the movement’s original demands for an “empowered parliament” and a “king who reigns but does not rule.”

Since independence from France in 1956, political life in Morocco has been dominated by an absolute monarch who tolerates elections but not all opposition. After protests in 2011 – dubbed the February 20 movement –King Mohammed VI enacted limited constitutional reforms and ran elections in 2011 that the State Department deemed “credible and relatively free from irregularities.” The Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD) won a plurality of seats in parliament, while 17 other parties also secured seats. But the king still has virtually unlimited authority to issue decrees, appoint cabinet members, dissolve parliament, command the armed forces, and oversee the judicial system. The PJD, despite holding the largest parliamentary bloc, has prioritized staying in power over pursuing meaningful reforms. Five years after the February 20 movement, Morocco’s political reforms have failed to meet the movement’s original demands for an “empowered parliament” and a “king who reigns but does not rule.” Iraqi democracy has been fragile ever since the fall of Saddam Hussein, which unleashed long-suppressed ethnic, sectarian and tribal rivalries. The rise of al Qaeda after the 2003 U.S. invasion and the 2014 conquest of a third of Iraqi territory by Islamic State exacerbated tensions. A series of democratically elected governments since 2003 have had difficulty establishing their legitimacy, largely because they failed to address the twin issues of sharing political power and oil revenues. Parliamentary elections in 2014 reflected widespread discontent within the minority Sunni minority, partly spurred by government crackdowns on Sunni protest camps in 2013. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was also accused of corruption, “mismanagement of security…and an improper concentration of power in the prime minister’s office.”

Iraqi democracy has been fragile ever since the fall of Saddam Hussein, which unleashed long-suppressed ethnic, sectarian and tribal rivalries. The rise of al Qaeda after the 2003 U.S. invasion and the 2014 conquest of a third of Iraqi territory by Islamic State exacerbated tensions. A series of democratically elected governments since 2003 have had difficulty establishing their legitimacy, largely because they failed to address the twin issues of sharing political power and oil revenues. Parliamentary elections in 2014 reflected widespread discontent within the minority Sunni minority, partly spurred by government crackdowns on Sunni protest camps in 2013. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was also accused of corruption, “mismanagement of security…and an improper concentration of power in the prime minister’s office.” Jordan has been a constitutional monarchy since 1952. The concentration of executive power in the crown and the monarchy’s dependence on loyalist tribes has allowed corruption and nepotism to become entrenched in politics. Jordan’s political spectrum reflects divisions between Palestinians and East Bankers, Islamists and non-Islamists, and rival tribes. Political parties, which were legalized in 1992, are relatively weak in the tribal-centric system. East Bankers from loyalist tribes tend to dominate the security forces and the government while Palestinians are underrepresented.

Jordan has been a constitutional monarchy since 1952. The concentration of executive power in the crown and the monarchy’s dependence on loyalist tribes has allowed corruption and nepotism to become entrenched in politics. Jordan’s political spectrum reflects divisions between Palestinians and East Bankers, Islamists and non-Islamists, and rival tribes. Political parties, which were legalized in 1992, are relatively weak in the tribal-centric system. East Bankers from loyalist tribes tend to dominate the security forces and the government while Palestinians are underrepresented. Since the 1952 ouster of the monarchy, Egypt has been led by former generals, with the exception of a brief experiment in democracy. Egypt’s political system has recently become even more authoritarian, despite high expectations for democracy after longtime President Hosni Mubarak was ousted in 2011. Capitalizing on new political openings, Islamists won a majority of parliamentary seats in 2011, and Mohamed Morsi was elected president in 2012. He was ousted by military coup after only one year in office. In 2014, Abdel Fattah al Sisi – a former general who led the coup against Morsi – was elected president. Observers noted “major flaws” in the election process, according to Freedom House. The election was also marred by low voter turnout, irregularities in the use of state resources, and voter intimidation.

Since the 1952 ouster of the monarchy, Egypt has been led by former generals, with the exception of a brief experiment in democracy. Egypt’s political system has recently become even more authoritarian, despite high expectations for democracy after longtime President Hosni Mubarak was ousted in 2011. Capitalizing on new political openings, Islamists won a majority of parliamentary seats in 2011, and Mohamed Morsi was elected president in 2012. He was ousted by military coup after only one year in office. In 2014, Abdel Fattah al Sisi – a former general who led the coup against Morsi – was elected president. Observers noted “major flaws” in the election process, according to Freedom House. The election was also marred by low voter turnout, irregularities in the use of state resources, and voter intimidation. The military looms as the ultimate arbiter of Algeria’s political process. After winning its independence from France in 1962, Algeria became a one-party system dominated by the National Liberation Front (FLN). A ban on political parties was lifted in 1988, and more than 50 parties competed in 1992 elections, among them the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). But when the FIS, an Islamist party, won the first round of parliamentary elections, the military led a coup against the president, nullified the results, banned FIS and arrested its leadership—a sequence that spawned a decade-long civil war and more than 100,000 deaths.

The military looms as the ultimate arbiter of Algeria’s political process. After winning its independence from France in 1962, Algeria became a one-party system dominated by the National Liberation Front (FLN). A ban on political parties was lifted in 1988, and more than 50 parties competed in 1992 elections, among them the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). But when the FIS, an Islamist party, won the first round of parliamentary elections, the military led a coup against the president, nullified the results, banned FIS and arrested its leadership—a sequence that spawned a decade-long civil war and more than 100,000 deaths. Libya’s political life has been dominated by armed factions vying for power – including the Islamic State – since the 2011 revolution that overthrew Muammar Qaddafi. Even before the revolution, political life was largely stifled. Qaddafi, who came to power in 1969, suppressed political parties, civil society, and the private sector. Local and tribal affiliations were often stronger than political identities.

Libya’s political life has been dominated by armed factions vying for power – including the Islamic State – since the 2011 revolution that overthrew Muammar Qaddafi. Even before the revolution, political life was largely stifled. Qaddafi, who came to power in 1969, suppressed political parties, civil society, and the private sector. Local and tribal affiliations were often stronger than political identities. Yemen has been in a state of political and humanitarian crisis ever since its Arab Spring protests began in 2011. In the uprisings, Yemenis called for the ouster of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had been in power for 33 years. Protests spread even though President Saleh agreed not to seek reelection, and crackdowns by security forces left hundreds dead. Initially, Saleh refused to sign a Gulf Cooperation Council brokered deal that would have ended his rule, but finally signed it in November 2011. He was replaced by his deputy in 2012, and a civil war began in 2014 between Houthi rebels from northern Yemen and those loyal to the existing government. The Houthis are a large clan of Zaydi Shiites who had been politically marginalized for decades. Freedom House dropped Yemen’s rating from 6 to 7 in 2016, due to “the collapse of the political system and the effects of an escalating civil war and related Saudi-led military intervention on the civilian population.”

Yemen has been in a state of political and humanitarian crisis ever since its Arab Spring protests began in 2011. In the uprisings, Yemenis called for the ouster of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had been in power for 33 years. Protests spread even though President Saleh agreed not to seek reelection, and crackdowns by security forces left hundreds dead. Initially, Saleh refused to sign a Gulf Cooperation Council brokered deal that would have ended his rule, but finally signed it in November 2011. He was replaced by his deputy in 2012, and a civil war began in 2014 between Houthi rebels from northern Yemen and those loyal to the existing government. The Houthis are a large clan of Zaydi Shiites who had been politically marginalized for decades. Freedom House dropped Yemen’s rating from 6 to 7 in 2016, due to “the collapse of the political system and the effects of an escalating civil war and related Saudi-led military intervention on the civilian population.” The Saudi royal family dominates almost every aspect of political life in Saudi Arabia. The ruling family has strong links to the ultra-conservative Wahhabi branch of Sunni Islam dating back to the 18th century. Clerics do not play a formal role in government, but they have been incorporated into the political establishment through the Senior Council of Ulama, the kingdom’s highest religious body. The council advises the king and provides endorsements for state policies. In 2009, the king extended membership for the first time to non-Wahhabi scholars.

The Saudi royal family dominates almost every aspect of political life in Saudi Arabia. The ruling family has strong links to the ultra-conservative Wahhabi branch of Sunni Islam dating back to the 18th century. Clerics do not play a formal role in government, but they have been incorporated into the political establishment through the Senior Council of Ulama, the kingdom’s highest religious body. The council advises the king and provides endorsements for state policies. In 2009, the king extended membership for the first time to non-Wahhabi scholars. Since independence from France, Syria has had a long history of instability, coups and wars, with elections that never had credibility. During 45 years under the Assad dynasty, Syria became one of the most authoritarian and brutal regimes in the Middle East. The protest movement spawned by the Arab Spring in 2011 was the largest in its modern history, but it quickly spiraled into civil war. It now involves pro-government forces, dozens of anti-Assad rebel groups with disparate interests, and extremist jihadis in ISIS and al Nusra Front. Regional intervention by rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as various levels of global intervention by the United States and Russia, have further complicated the matter. Presidential elections were held in 2014, but they were widely criticized by democratic countries as illegitimate since it was held in government-controlled areas during an ongoing civil war.

Since independence from France, Syria has had a long history of instability, coups and wars, with elections that never had credibility. During 45 years under the Assad dynasty, Syria became one of the most authoritarian and brutal regimes in the Middle East. The protest movement spawned by the Arab Spring in 2011 was the largest in its modern history, but it quickly spiraled into civil war. It now involves pro-government forces, dozens of anti-Assad rebel groups with disparate interests, and extremist jihadis in ISIS and al Nusra Front. Regional intervention by rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as various levels of global intervention by the United States and Russia, have further complicated the matter. Presidential elections were held in 2014, but they were widely criticized by democratic countries as illegitimate since it was held in government-controlled areas during an ongoing civil war.