Interview with Fatemeh Haghighatjoo

By Semira N. Nikou

Dr. Fatemeh Haghighatjoo is a former member of Iran’s parliament (2000-2004). She is currently a visiting professor at the University of Massachusetts in Boston.

This is the seventh in a series on parliamentary elections due in March 2012:

- What role have women played in Iran's parliament since the 1979 revolution?

Women in parliament can be divided into two groups: those who have a feminist conscientiousness or awareness, and those who do not.

Once we, the reformists, won the election in 2000, we began having meetings and seminars with women’s rights activists. Our promise during the sixth parliament (between 2000 and 2004) was to change discriminatory laws against women.

There were women and men who defended women’s rights. On one bill related to women’s issues, one of our male colleagues told us, “It is important that as a member of the clergy, I defend this bill, rather than you women having to defend it.” So the sixth parliament had a very different atmosphere than subsequent parliaments.

Zahra Rahnavard—then president of Al Zahra University and wife of opposition leader Mir Hossein Mousavi—sponsored one of our seminars. It explored which women’s issues should be prioritized in parliament. All of the female MPs formed a caucus to address these issues. Even though some of the 13 women had values, they had all been elected on a reformist platform.

But women have played different roles since in the seventh (2004 to 2008) and eighth parliaments (since 2008). In both parliaments, women have been very patriarchal. Unfortunately, they have not challenged any gender inequalities that are justified in the name of Islam. For instance, they defend polygamy because they consider it an Islamic value. They also defend segregation and the gender division of labor.

In another example, Eshragh Shaegh—a representative from Tabriz in the seventh parliament—said that if ten prostitutes were executed, there would not be any more prostitution in the country since it would be considered too dangerous or criminal.

- Why did conservative women dominate the recent parliaments?

There is an unwritten rule that some women have to be candidates for parliamentary elections. Since the 1979 revolution, most political parties have included at least two women in their lists for Tehran and other large cities.

But the Guardian Council, which acts as a vetting body, banned reformists from participating in 2004 and 2008. More than 2,500 reformist candidates were disqualified. Only those seen as loyal to the regime were allowed to run. So conservative women won.

- What type of women--political affiliation, religious background, social class--generally run as candidates?

Non-Islamic women cannot run for parliamentary elections, which is the case for both men and women. Only those who are loyal to the regime and the supreme leader (velayat-e faqih) can participate. So from the ideological perspective, we can say that only religious women can run.

In terms of social background, we often see women from the middle class. For example, many teachers have run as candidates.

Some female candidates have also been relative to authorities, such as:

- Gohar Dastgheib (daughter of Grand Ayatollah Dastgheib)

- Ategheh Rajai (wife of former President MohammadAli Rajai)

- Faezeh Hashemi (daughter of former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani)

- Azam Taleghani (daughter of Ayatollah Mahmoud Taleghani)

- Jamileh Kadivar (wife of former minister Ata’ollah Mohajerani and sister of Mohsen Kadivar)

- Fatemeh Karoubi (wife of former speaker of Majles and opposition leader Mehdi Karoubi).

In politics, family ties are is important, and not just for women. For example, Mohammad Reza Khatami got the most votes in the sixth Majles because of his relation to the (then President) Mohammad Khatami. The two are brothers.

For example, Soheyla Jelodarzadeh (member of the fifth, sixth, and seventh parliaments) had no family connections. She represented the Islamic Labor Party (Hezb-e Eslamieh Kar) in parliament. I represented the Islamic Iran Participation Front (Jebheye Mosharekate Iran-e Eslami) as well as the student movement. I was active as a student, which led to my inclusion on the political list. In most cases you have to be supported by one of the political wings.

But Iran has also had independent women who do are not affiliated with a political party and do not have a family relation.

- Which women tend to get more votes?

It depends on the period. Different types of women have been voted into office, based on the atmosphere of society at the time.

For example, Faezeh Hashemi came in near the top of the list of candidates from Tehran in the fifth parliament (1996-2000) not just because she was the daughter of former President Rafsanjani, but because her campaign promises and personal actions—such as riding a bicycle—were attractive, particularly to young women.

But even though she did well in the fifth parliament election, she lost in the next election]. She played the family card; she ran as the daughter of Rafsanjani--a move that was not popular at the time.

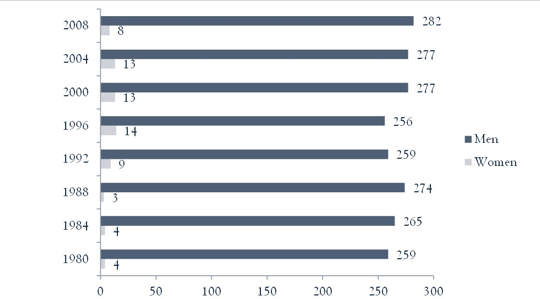

- Why has the number of female parliamentarians decreased since 2004?

The role conservative women played in the seventh parliament (2004 to 2008) caused women to question whether female parliamentarians would in fact work in their favor. The patriarchal positions of conservative parliamentarians probably affected the voting pattern. As a result, Iran did not have female candidates who could represent women’s needs and issues in the seventh and eighth parliaments.

- What positions do female parliamentarians generally hold on issues affecting women—such as on divorce or controversial family laws?

Changes favoring women have often been drafted by female parliamentarians. As a general pattern, women in all parliaments have tried to liberalize the law—even if by a little bit-- in favor of women. Personal status laws, such as divorce laws, have been the main issues that female MPs have tried to revise. But each time they have only made minor changes. We still have not been able to bring equality in divorce.

The controversial family protection bill (that would allow men to marry additional women without the consent of their first wife, among other issues) introduced to the seventh parliament actually came from the government--the judiciary and the president's office.

The women’s movement in Iran has played an important role in influencing parliamentary positions on women’s issues, especially on the family protection bill. But female parliamentarians are not necessarily sympathetic toward the women’s movement. The women in the seventh parliament (2004 to 2008) and eighth parliament (since 2008) are very traditional; many support polygamy.

The women’s movement has been able to organize and speak with unity—from the secularists to the Islamists as well as from the left to the right—against issues such as polygamy, which would be allowed under the family protection bill. Why do you think the family protection bill of has been sitting in parliament for the past seven years? It has not passed because of the independent women’s movement’s opposition.

This women’s activism in society and the bottom-up pressure on the parliament and the clergy have been a success story for the independent women’s movement. They reflect how even the conservative parliament can be pushed toward policies favoring women.

Source: Duality by Design: The Iranian Electoral System published by the International Foundation for Electoral Systems.

Click here to read Iran's Revolutionary Guards Soar in Parliament

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org