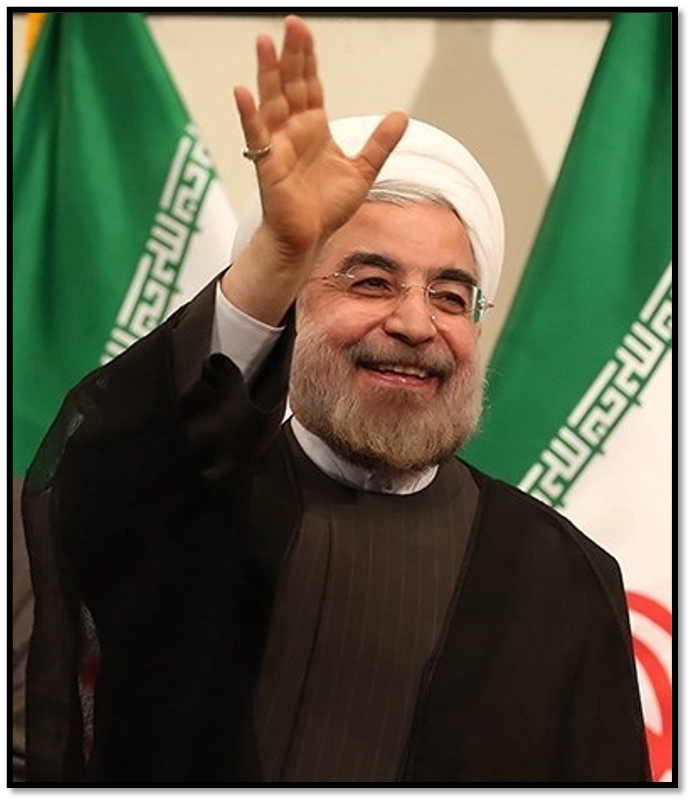

The leaders of the Green Movement remained under house arrest and the leaders of the Khatami era reform movement decided to sit out the 2013 presidential elections. Competing against a field of mostly conservative candidates, Rouhani received 51 per cent of the vote. The runner-up, Tehran mayor Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, a moderate conservative, received 17 percent of the vote, indicating a preference by voters for a return to the politics of the center. Rouhani’s election also marked a return of reformers to office. Unlike the Khatami team, however, Rouhani aimed not at sweeping reform but at a limited, gradualist approach.

As president, Rouhani immediately set about improving relations with the international community. Aided by his foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, he resumed negotiations with the world’s six major powers —Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States — on Iran’s nuclear program. He struck a conciliatory tone in his address to the U.N. General Assembly in September 2013. Before leaving New York, he held a telephone conversation with President Obama — a first between an Iranian and American president — in which the two leaders discussed possible areas of future cooperation. (Iran’s supreme leader later described the conversation as “inappropriate,” and no such discussion occurred during Rouhani’s General Assembly trip in the following year).

In a sign of the improving environment, the Emir of Kuwait visited Iran in June 2014. Zarif spoke and wrote opinion pieces on possible cooperation with regional and world powers on resolving conflicts like the Syrian civil war. He planned a visit to Saudi Arabia. The rise of the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, posed a threat both to the United States and Iran. For a moment, it appeared that the two countries could cooperate in Iraq and Syria against this common enemy.

In a sign of the improving environment, the Emir of Kuwait visited Iran in June 2014. Zarif spoke and wrote opinion pieces on possible cooperation with regional and world powers on resolving conflicts like the Syrian civil war. He planned a visit to Saudi Arabia. The rise of the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, posed a threat both to the United States and Iran. For a moment, it appeared that the two countries could cooperate in Iraq and Syria against this common enemy.

The centerpiece of Rouhani’s policy was a resolution of the nuclear issue. He and his team believed that once the nuclear issue was addressed, sanctions would be lifted, economic activity would pick up, foreign investment would flow in, and Iran could begin to integrate itself further into the international community. Negotiations with the world’s six major powers occupied much of the first two years of Rouhani’s presidency. An interim agreement was reached in November 2013. A target date of November 2014 for a final accord was missed; but a framework was hammered out in April 2015.

After marathon negotiations, Iran and the world’s six major powers reached a final deal on July 14, 2015. The landmark agreement – known by its acronym as the JCPOA – or the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action – included strict limits on the number of operating centrifuges Iran could maintain for 10 years, caps on fuel enrichment and enriched fuel stocks, and redesign of or limits on nuclear facilities at Fordo and Arak to block alternate paths to nuclear weapons. Iran and the International Atomic Energy Agency also agreed on a “roadmap” to account for Iran’s past nuclear activities and allow an intrusive inspections regime. In exchange, Iran is to get phased relief from all nuclear program-related sanctions. In anticipation of the lifting of sanctions, European and American businessmen began to show up in Tehran, looking for future investment opportunities.

The Rouhani-Zarif team succeeded, through considerable effort, dexterity and determination, to reach an agreement with the world powers over Iran’s nuclear program; but other sources of tension between Iran and the West remained to be addressed. Iran did not alter its official position that the state of Israel was illegitimate and should not exist. Iran continued to support and arm Hezbollah in Lebanon and groups opposed to Israel in the Gaza Strip. The United States continued to designate Iran as a state sponsor of terrorism. Relations with the Arab Gulf states, led by Saudi Arabia, worsened. In the Syrian civil war, Iran supported President Assad while Saudi Arabia and its allies backed his opponents. The appearance of Hezbollah fighters in Syria (and, on one occasion, an Iranian Revolutionary Guards officer on the Golan Heights) and Iranian arming and training of Shiite militias in Iraq further alarmed the Saudis. Iran and Saudi Arabia also supported opposite sides in the Yemeni civil war. Above all, Saudi Arabia and its Arab allies feared that a nuclear accord would fail to block Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon and signal American acquiescence to Iran’s growing regional role.

At home, Rouhani began the difficult task of addressing economic problems inherited from the Ahmadinejad administration. The slippage in the currency value was halted and the dollar-rial exchange rate was stabilized. Inflation was slowed down. Runaway government spending was slightly curbed. The contraction of the economy was reversed, and by his second year in office the economy began to register modest growth. Rouhani was also publicly critical of the Revolutionary Guards’ large role in the economy. His attempt, however, to ease the high cost of subsidy reform by asking better-off Iranians voluntarily to give-up the monthly stipend available to all Iranians failed; the roll of subsidy recipients began to be cut, moderately and by government fiat, anyway. And midway into his first term, it remained unclear whether Rouhani would find a way of addressing two major economic issues: the monopolistic hold of the Revolutionary Guards, para-statal organizations and privileged individuals over large sectors of the economy and the shaky state of several major banks with large portfolios of non-performing loans.

Under Rouhani, there was a palpable easing of social controls and book censorship, and occasionally a vigorous debate took place in the press on major issues of the day. Rouhani himself spoke out on matters of civil and individual rights. With an eye to the activities of the morals police, he said morality could not be imposed with clubs and force. He called for less interference with student activities on university campuses and more open access to the internet. For the president to publicly address these issues was a novelty. But it became clear that, aside from suasion, the president exercised little control over the judiciary or the intelligence ministry. Arrests of dissidents, human rights and women’s rights activists, and human rights lawyers continued. The revolutionary courts continued to issue severe prison sentences for mild political offenses. Despite an implicit campaign pledge, Rouhani was unable to secure the release of Green Movement leaders Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi from house arrest. Executions continued at their previous pace. Newspapers continued to be shut down or editors and journalists to be arrested for offending articles.

Rouhani was elected to a second term in 2017 by a comfortable margin, but his second term was fraught with challenges in both domestic and foreign policy. At home, protests erupted in Mashhad, Iran’s second largest city, in December 2017 and spread to other towns. The protests, in which several demonstrators were killed, were attributed to economic discontent and to Rouhani’s failure to deliver on his promises of reform and liberalization, jobs, and improved relations with the international community. Significantly, protestors also denounced the costs of Iran’s involvements in Syria and Lebanon, calling for such monies to be devoted to pressing needs at home.

Rouhani also made little headway in reigning in the security agencies or curbing the Revolutionary Guards’ expanding role in the economy or in domestic security matters. The Revolutionary Guards’ security arm arrested dissidents and dual nationals. Rouhani’s lack of control over the security agencies was demonstrated in February 2018 when the French government thwarted a plot to bomb a meeting of an Iranian opposition group in Paris. One Iranian diplomat was arrested in Germany and two in Belgium in connection with the plot.

Protests broke out again in November 2019. In a surprise overnight announcement, Iran hiked gas prices—by up to 300 percent—and introduced a new rationing system. The government’s goal was to raise funds to help the poor, but it backfired. Protests spread across the country. Demonstrators torched hundreds of buildings, including banks, gas stations, and government offices. Security forces dispersed crowds with tear gas and live ammunition. The government cut off access to the internet for nearly a week until the demonstrations stopped. At least 208 people were killed in clashes, according to Amnesty International.

In early 2020, Rouhani faced the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The first official report of deaths from the new virus was on February 19, 2020. Rouhani initially downplayed the threat. But his tone changed by mid-March, when Iran reported nearly 13,000 cases and more than 600 deaths from the virus. In April, Iran requested a $5 billion emergency loan from the International Monetary Fund to cope with the pandemic. Iran never got the loan. The government struggled to provide healthcare to the sick and economic relief to impoverished families. More than one million people – in a labor force of 27 million – lost their jobs in 2020. By late July 2021, four waves of infections had killed more than 89,000 people. The highly contagious Delta variant threatened a fifth wave amid a slow vaccine rollout during Rouhani’s last weeks in office.

During Rouhani’s final weeks in office, Iran suffered power outages and water shortages during a summer heat wave and drought. The twin crises triggered protests in major cities, including Tehran, and several provinces starting in July 2021. Demonstrators burned tires, blocked roads and chanted anti-regime slogans, including “Death to the dictator.” Rouhani said that citizens “have the right to speak, express themselves, protest and even take to the streets within the framework of the regulations.” But he also suggested that internal opposition and Iran’s adversaries were contributing to the unrest.

In foreign policy, Rouhani’s second term was dominated by the consequences of the Trump Administration’s withdrawal from the JCPOA and the reimposition of sanctions in 2018. The sanctions sought to curtail Iran’s ability to export oil, conduct business through the international banking system, import and export goods, and attract foreign investment. The impact of the sanctions on Iran’s economy, already hampered by mismanagement at home, was severe. Iran’s oil exports and revenues dropped sharply. The value of the rial against the American dollar plummeted. Inflation soared. International banks grew wary of facilitating Iranian dollar transactions, hampering Iran’s foreign trade; and the sanctions discouraged international firms from pursing projects in Iran. As a result, the foreign investment that Rouhani anticipated after the JCPOA did not materialize.

The Islamic Republic continued to comply with its obligations under the JCPOA for 14 months after Trump abandoned the JCPOA. In July 2019, Tehran began breaching the agreement. Its moves were initially incremental and calibrated until the assassination of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, a top nuclear scientist, on November 27, 2020. Three days later, Iran’s parliament, which was dominated by conservatives, passed a bill demanding that the government immediately enrich uranium to 20 percent, a step closer to producing fuel sufficient for a bomb. The new legislation restricted U.N. nuclear inspections if U.S. sanctions on Iran's banking and oil sectors were not lifted within a month. Rouhani opposed the bill because it could harm diplomacy. The Guardian Council passed a modified version of the law that extended the deadline for sanctions relief from one to two months.

Tensions between Iran and the United States escalated again in early 2020. On January 3, President Trump ordered an airstrike on a convoy of Iranian and Iraqi military leaders leaving Baghdad’s airport. The drone attack killed seven people including General Qassem Soleimani, the head of the Revolutionary Guards’ elite Qods Force. Washington alleged that Soleimani was planning attacks targeting U.S. personnel and interests in the region. The Pentagon announced the deployment of 3,500 additional U.S. troops to the region after Supreme Leader Khamenei vowed “severe revenge” for the killing of Soleimani.

On January 8, Iran responded by firing more than a dozen missiles at two Iraqi military bases housing U.S. troops. No U.S. or Iraqi personnel were killed, but more than 100 suffered brain injuries. Foreign Minister Zarif said that Tehran did not seek war or further escalation. Rouhani said that Iran’s goal was to get U.S. forces to leave the region. Several hours after the Iranian attack, the Revolutionary Guards mistakenly shot down Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752. All 176 people on board were killed. On January 11, a Revolutionary Guards general admitted fault for the incident. Iranians protested the government’s incompetence and for initially denying responsibility. “Death to the liars,” people shouted during protests in Tehran.

After President Joe Biden’s inauguration in 2021, Iran and the United States agreed to renew diplomacy on terms to restore full compliance with the JCPOA. From April to June 2021, Iran and the world’s six major powers held six rounds of talks in Vienna. Iran refused to meet directly with the United States; it negotiated through an E.U. mediator and the five countries still in the accord.

The talks stalled during and after the June 18 presidential election, which was won by Ebrahim Raisi, the hardline head of the national judiciary. Iran said that it would not return to Vienna for a seventh round of talks until after Raisi’s inauguration on August 5. “We’re in a transition period as a democratic transfer of power is underway in our capital,” Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi tweeted. Rouhani’s most ambitious project—and one of the most important overtures to the United States since the 1979 revolution—remained unfulfilled at the end of his presidency.

Shaul Bakhash is the Clarence Robinson Professor of History Emeritus at George Mason University.