By Garrett Nada

Iran’s 2020 parliamentary election, following months of internal protests and showdowns with the outside world, will be a stark contrast to the last poll in 2016, when Iranians believed they were emerging from years of economic sanctions and political isolation. Voters go to the polls on February 21 in an atmosphere fraught with frustration and anger. Iran is far worse off — squeezed economically, divided politically, and exposed militarily — than it was four years ago.

The main issue in the February 21st poll is Iran’s dire economic situation, which increasingly impacts all strata of society. Business and political elites no longer have buffers since the United States reimposed economic sanctions in November 2018. Iran’s ability to sell oil, its primary source of revenue, has been curtailed by at least 80 percent. The value of the rial has plummeted, while inflation has soared. The World Bank estimated that Iran’s economy shrank by nearly nine percent in 2019.

Public outrage triggered protests in November 2019 and in January 2020 that challenged the theocratic system and its leaders. Meanwhile, the prospect of war with the United States has loomed in the background.

The biggest issue may be how many Iranians actually vote. The regime cites turnout as a reflection of public support. In 2016, 62 percent voted. Turnout may be dependent on the choice of candidates. The election system is engineered by the powerful — and unelected — Guardian Council of 12 clerics and Islamic scholars. It vets all candidates. As of early February, it had approved only 43 percent of candidates who registered to run, compared to 51 percent in 2016, which had been a record-low percentage. It rejected many reformists, including incumbents, who favor social openings or economic reforms. So, the next parliament may be dominated by conservatives, regardless of the turnout. In the past, higher turnouts have often favored reformist factions. The following is a rundown of issues in the 2020 parliamentary election.

The Economy

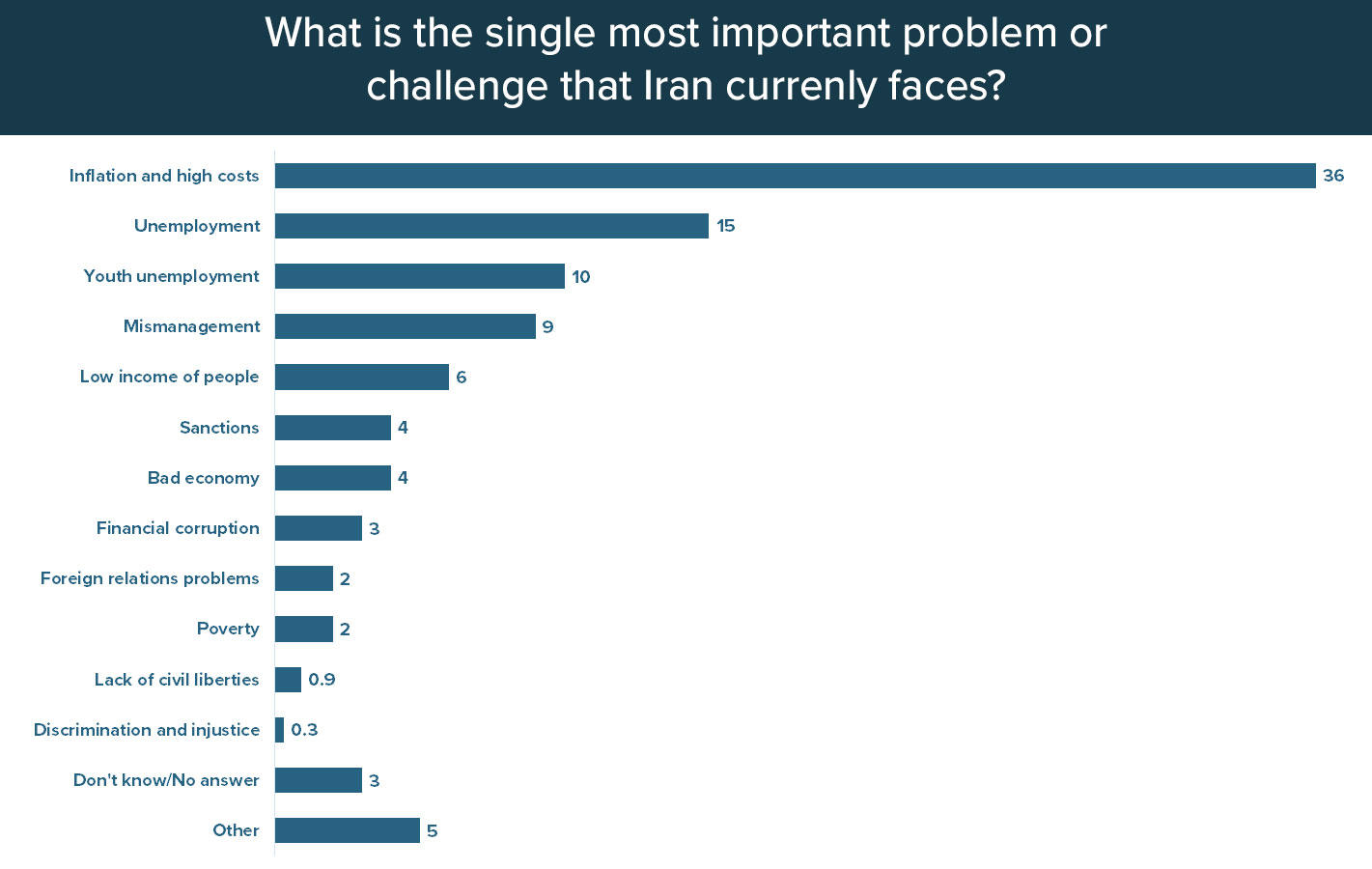

For Iranians, elections are often decided on pocketbook issues. In 2019, 89 percent of respondents to a national survey cited economic issues as the top challenge facing Iran. It revealed that 68 percent of Iranians polled said that the economic situation was bad, and 55 percent said that it was getting worse.

Job creation has become a key issue, especially for Iranian youth born since the 1979 revolution. They now constitute the largest bloc in the population of 82 million. Between 2010 and 2020, some eight million people joined the work force, but only about a million jobs were created. As of June 2019, overall unemployment was nearly 11 percent, while unemployment hit 24 percent for the young between 15 and 29. Many have been unable to marry or move out of their parents’ homes.

More than a third of respondents to a national survey said inflation and high costs were Iran’s top challenge.

Source: “Iranian Public Opinion under ‘Maximum Pressure,’” Center for International & Security Studies at Maryland and IranPoll.com

The U.S. “maximum pressure” campaign entered a new phase in May 2019, when the Trump administration announced that it would also impose sanctions on any country that bought Iranian oil. By late 2019, Iran’s oil exports were down to less than 500,000 barrels per day, a huge decline from exports in 2016 that reached 3.2 million barrels a day.

Inflation has also increased the price of basic goods. By April 2019, the price of meat products had skyrocketed by 116 percent compared to the previous year. Food prices were up 30 percent in December 2019 compared to 2018, according to the Iran Statistical Center. Senior officials even suggested eating less or fasting to show the United States that Iran can resist its sanctions. The World Bank estimated that inflation would average 38 percent in fiscal year 2019/2020 and that GDP growth would be zero.

In November 2019, protests swept 100 cities over a price hike in fuel and a new fuel rationing system. The interior ministry claimed that 731 banks, 140 government buildings and 70 gas stations were burned. Demonstrators reportedly chanted anti-government slogans. More than 300 people were killed and thousands more were injured in the subsequent crackdown, according to Amnesty International. The protests were the most serious since demonstrations in December 2017 and January 2018, which were also sparked by deteriorating economic conditions.

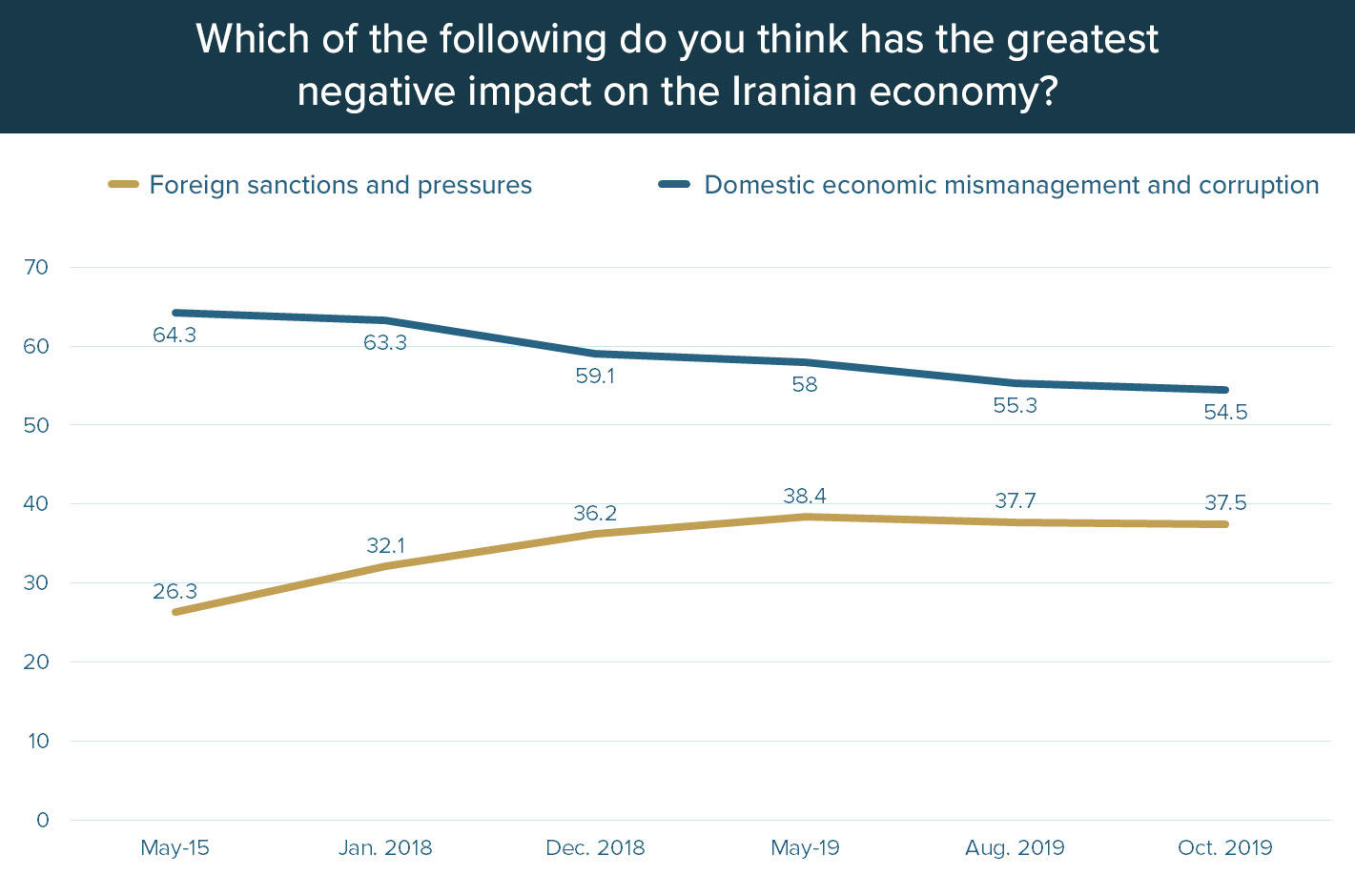

Not all of Iran’s economic problems have been caused by sanctions. Since 2015, a majority of Iranians have consistently cited domestic mismanagement and corruption — rather than foreign pressure — as having the most negative impact on the economy. In October 2019, only 38 percent of respondents said foreign pressure had the most negative impact on the economy.

Source: “Iranian Public Opinion under ‘Maximum Pressure,’” Center for International & Security Studies at Maryland and IranPoll.com

Ahead of the 2020 poll, Edalatkhahan (or Justice Seekers), a group of young conservatives, launched an anti-corruption campaign. The group has been primarily active on university campuses in Tehran and other major cities. It has supported efforts by Ebrahim Raisi, the hard-line chief of the judiciary, to root out corruption. Ideologically opposed to reformists, the Justice Seekers have also been critical of establishment conservatives, who they see as participants in systemic corruption.

The election outcome is important, even though the economy is largely run by the executive branch, because the next parliament will play a key role in supporting – or stymying – the agenda of whoever is elected to the presidency in 2021.

Regime Accountability

On the eve of the election, public confidence in government had visibly eroded because of the shooting down of a Ukrainian passenger plane on January 8. All 176 people on board were killed; 140 passengers were Iranian. The regime denied responsibility for three days. Iranians, enraged at government and military incompetence, launched new protests that lasted almost a week. “Death to the liars,” people shouted in Tehran.

The government’s credibility took a further blow when three presenters for state TV quit in anger over the government’s handling of the tragedy. “It was very hard for me to believe that our people have been killed,” Gellare Jabbari, an anchor for IRIB, said on Instagram. “Forgive me that I got to know this late. And forgive me for the 13 years I told you lies.”

Public confidence in the election system is a related issue. In all 10 parliamentary elections since 1980, the Guardian Council has rejected anywhere from 15 percent to 49 percent of candidates who registered to run. The vetting ahead of the 2020 election has been especially stringent. The Guardian Council initially rejected more than 9,000 of the more than 14,000 hopefuls. The panel rejected 90 incumbent lawmakers as well as many reformist and centrist candidates on vague grounds of “financial and moral corruption.” It was the largest number of disqualifications since 1980, although many candidates appealed for reinstatement. By February 1, the Guardian Council had approved an additional 2,000 candidates.

The reformists protested the vetting by not fielding an electoral list in Tehran. “There is no possibility of fair competition for the deep-rooted reformist camp,” said the Reformists’ Supreme Policy-Making Council in a statement. The capital has the largest share of parliamentary seats — 30 of 290 — of any provincial bloc. In the 2016 election, Rouhani’s allies defeated hardliners and took all 30 seats in Tehran. The umbrella group of reformists, however, called on reformist councils outside of the capital to field candidates as they saw fit.

President Hassan Rouhani lashed out at the Guardian Council, which is dominated by hardliners, for not approving a more diverse spectrum of candidates. “Do not tell the people that for every seat in parliament there are 17, 170 or 1,700 candidates running in the election,” he said in a televised address on January 15. “Seventeen-hundred candidates from how many factions? Seventeen candidates from how many parties? From one party? This is not an election.” Despite his objections, Rouhani encouraged people to vote.

Foreign Policy

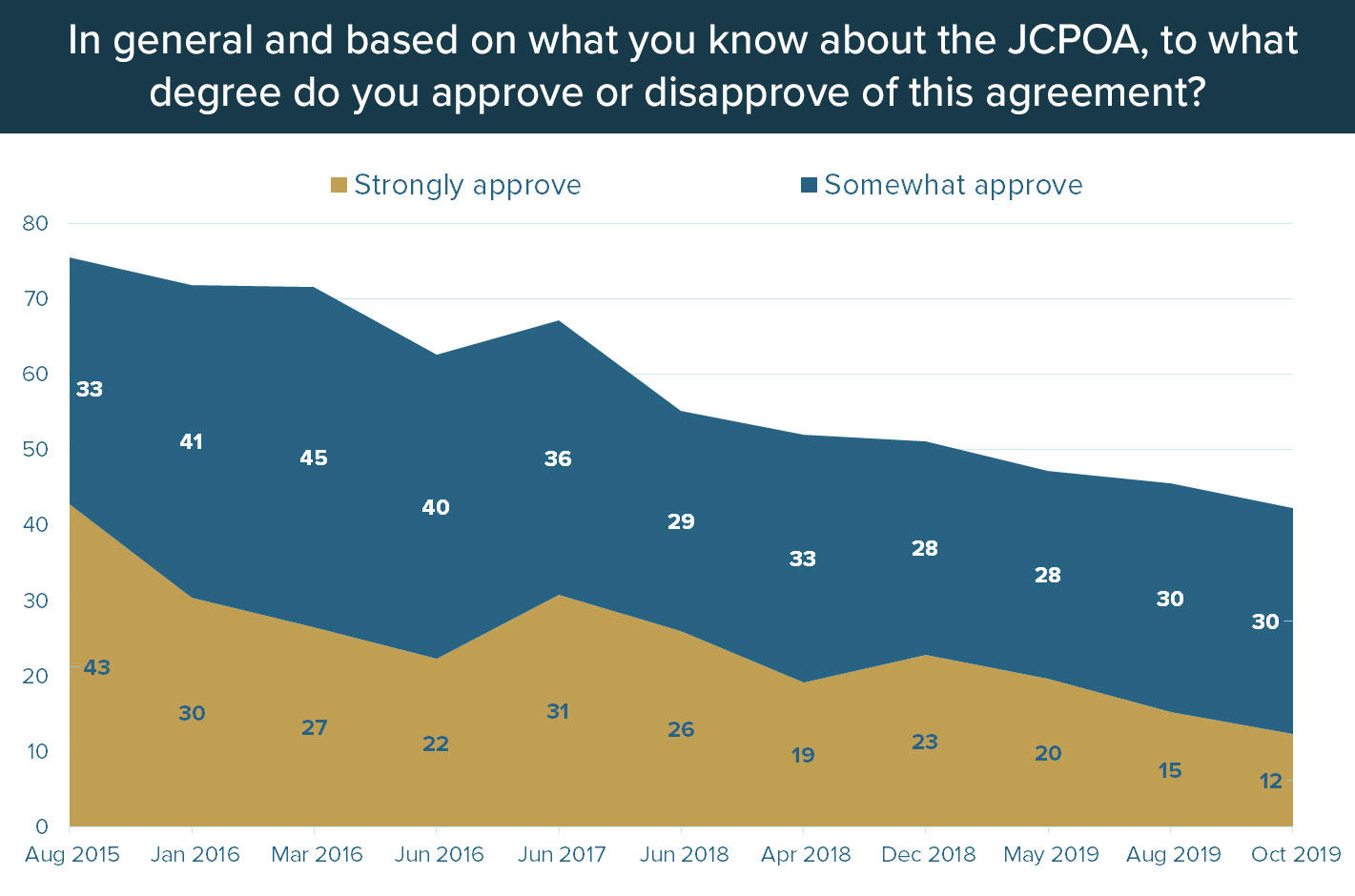

Foreign policy is a subtext of the election, given recent tensions with the United States and the eroding 2015 nuclear agreement. President Rouhani and his allies in parliament staked their political capital on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). But the agreement, concluded after two years of intensive talks with six world powers, failed to deliver the promised economic benefits. Since the U.S. withdrew from the JCPOA in May 2018, Iranians have become increasingly disillusioned with the accord. By October 2019, less than half of Iranians approved of the JCPOA. Iranians have voiced strong support for the government’s rolling back of its commitments to the deal.

Shortly after the nuclear deal was brokered in 2015, 75 percent of respondents approved of the JCPOA. By October 2019, support was down to 42 percent.

Source: “Iranian Public Opinion under ‘Maximum Pressure,’” Center for International & Security Studies at Maryland and IranPoll.com

Iranians have also been increasingly concerned about the prospect of war with the United States that could further tax the struggling economy and isolate the Islamic Republic. Tensions reached new heights after the United States killed Qassem Soleimani, the head of the elite Qods Force, in a drone strike on January 3 in Iraq, and Iran responded with missile attacks on U.S. forces at Iraqi bases.

For more election coverage see:

Trends in Past Parliamentary Elections

Photo Credits: Tasnim News Agency [CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)]; President.ir