Hadi Semati is a former professor in the faculty of Law and Political Science at Tehran University and a former scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He is now an independent analyst.

What is the state of Iran’s revolution on its 43rd anniversary on February 11, 2022? In what ways is the Islamic Republic strong? And in what ways is it weaker or more vulnerable?

The Islamic Republic in 2022 is a stronger, more centralized and more institutionalized state than the Pahlavi monarchy ever was. Iran has capable institutions of coercion, including multiple, sometimes rival, and often overlapping intelligence and security services. Iran, compared to its neighbors, is remarkably secure in both urban and rural areas. The state has a near total monopoly on weapons. Iran also has functioning institutions that distribute subsidies and services to the population. The ideology espoused by the leadership is fairly coherent and to a fair degree reproduced.

Iran’s main weakness is the growing divide between the state and civil society. For much of the populace, the state’s legitimacy has eroded considerably since the 1980s. It has fallen short of the promises of the 1979 revolution. As a result, the state has increasingly relied on coercion to maintain its hold on power. Paradoxically, the strength of the state has become the source of its weakness.

How would you rate or grade the revolution’s fulfillment of its early promises? In what ways has it fallen short?

Most revolutions have not fulfilled their promises. Iran is no exception. The three principal slogans of its revolution were independence (istiqlal), freedom (azadi) and Islamic Republic (Jomhouri-e Eslami).

On independence, Iran has managed to carve out a foreign policy that is less reliant on great powers than the monarchy. During the Cold War, Iran was firmly in the camp of the United States. Iran and Saudi Arabia were the two guarantors – the “twin pillars” – of U.S. interests in the region. The revolutionaries resented U.S. influence. Since the revolution, the mantra has been “Neither East, nor West, Islamic Republic.” Iran has not been as dependent on foreign powers, though it has grown close to non-Western powers, including China – its biggest oil customer – and Russia.

On freedom, Iran has fallen far short of the revolution’s promise. Both social and political freedoms have been restricted. In the 1980s, thousands of political prisoners were executed. The degree of tolerance of dissent has vacillated over the decades, but overall, freedoms have not been institutionalized. The constitution, a hybrid that includes both European and Islamic influences, ostensibly protects freedom of expression but allows for many exceptions. For example, it criminalizes offenses such as “spreading propaganda against the system” and “insulting the Supreme Leader” – without defining them. Repression has often seemed arbitrary.

On the concept of Islamic Republic, Iran has failed to balance the two concepts of “Islamic” and “Republic.” Read literally, Iran should be a republic that is Islamic in content and character. And republic implies that the state should be a representation of the public. But as Iran has narrowed the political space and quashed popular dissent, the state has become much less dependent on the will or voice of the people. The post-revolutionary constitution is a document that establishes the convoluted boundaries of power and responsibility, but the actual power distribution is a totally different creature.

At the same time, Iran is far from a totalitarian state. It still has a very loyal base of support that many outside observers discount. And even many of the regime’s critics grant the state some degree of legitimacy.

Social justice was an important component of the Islamic Republic concept. Iran has a mixed record on this issue. The new regime vastly improved social and economic indicators in many parts of the country, especially in rural areas. The state expanded access to water, electricity, education, and healthcare to the working class. So in some ways, the Islamic Republic did uplift the downtrodden (mostazafin) who were neglected by the monarchy. Yet poverty is still a major issue. The gap between the rich and the poor is wider in 2022 than in the 1980s. And many families are dependent on government subsidies to meet their basic needs.

Many Iranians, however, do not measure the Islamic Republic’s success in terms of statistical data or macroeconomic indicators. Given the country’s vast natural resources and pride in the ancient Persian civilization, Iranians feel entitled to a better standard of living. They compare Iran to Western powers, not neighboring and developing countries.

The Islamic revolution, however, is a work in progress for many across the political spectrum. Iran is still evolving. And the legacy of the revolution and the early goals still animate the political debate.

How has the government’s agenda shifted—in some cases far afield—from the early goals?

The early goals are still on the agenda and are loudly espoused by the leadership. But national security has often taken precedence, and lack of resources and vision have made reaching those goals almost impossible. Many of the revolutionaries were naïve in their plans to allocate vast amounts of resources to public services and domestic issues in general. Iraq’s invasion of Iran in 1980 and the ensuing eight-year war was an early reality check. Iran’s subsequent spending on its military and security and intelligence apparatus – though significantly lower than neighboring and similar size countries – has been driven by external forces beyond Iranian control as well as paranoia about domestic dissent.

How has Iran’s political spectrum evolved since the 1979 revolution? How have parties and political factions changed?

In the 1980s, a clear dichotomy quickly emerged between the leftists and the conservatives. There were many factions within these two camps. But, generally, the conservatives favored a bazaar or a more laissez-faire economy compared to the leftists, who wanted a more socialist or communist approach. The conservatives also tended to be much more religious and traditional on social issues.

After the 1980-1988 war with Iraq, many leftists entered universities as Iran entered an era of reconstruction. An intellectual revolution happened on campuses. The students started assessing where the revolution went wrong or fell short and what should be done to correct those mistakes. Many of these students were religious in their private lives but had outlooks akin to European social democrats. They were not in favor of a state-imposed version of Islam.

The resulting reformist movement propelled Mohammad Khatami – a dark-horse candidate and a liberal-minded cleric – to the presidency in 1997. The rivalry between reformists and conservatives has been the primary division in politics since then.

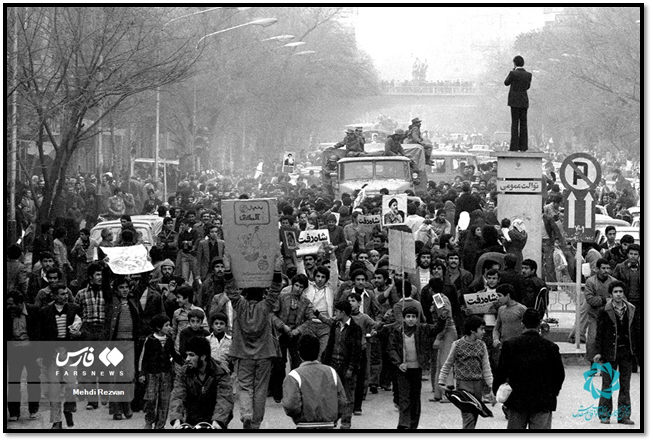

The 14-months of protests that led to the demise of the U.S.-backed monarchy included an eclectic mix of leftists, nationalists, liberals, and Islamists who were united in their opposition to the monarchy. What percentage of that coalition is still loyal to the revolution? Who defected or went into opposition?

The Iranian revolution was a massive social movement that spanned ideological factions and economic classes. That was a major reason the monarchy fell so quickly. But this broad coalition collapsed within a few years. The leftists miscalculated the strength of the conservatives, especially the clerics who backed Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The clerics had an unparalleled organizational capacity through the mosques as well as moral standing in the public eye. Their ground game was more firmly rooted in Iranian culture and history than the narrative that the secular left was offering.

At the same time, the clerics quickly grew paranoid about the more secular forces and opening Iran up to foreign influence. They were concerned that the revolution might be stolen. Their paranoia was fed by the armed resistance of Marxist groups, especially the Mujahedeen-e Khalq (MEK). Several groups in Kurdistan, in western Iran, also took up arms against the state in the 1980s.

The new regime brutally suppressed these groups. The MEK, for example, went underground in 1981 and many of its members went to Iraq, Europe or elsewhere. Many of the Kurdish communist or socialist groups fled to Iraq. By the mid-1980s, most leftists had been marginalized, exiled or killed. But some of the original leftists cooperated with the new generation of reformists in the late 1990s. The actions of the armed groups and non-violent opposition inadvertently pushed the conservatives to consolidate power and radicalize the revolution.

The regime put down another wave of opposition in the aftermath of the 2009 presidential election. The “victory” of conservative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad over reformist Mir Hossein Mousavi was widely disputed and sparked the creation of the opposition Green Movement. Authorities brutally suppressed mass protests and held show trials to make examples of the movement’s leaders. In 2011, Mousavi, a former prime minister, and Mehdi Karroubi, another presidential candidate and former parliamentary speaker, were put under house arrest. They and their supporters were labeled “seditionists.”

How much political diversity does the regime tolerate in 2022?

Unfortunately, not much. In the aftermath of the 2009 presidential election, the authorities referred to the Green Movement leaders and their followers as traitors and stooges of foreign governments, especially the United States. This constrained political expression until the election of Rouhani in 2013. He ran on a platform of moderation and sought to curb state interference in the private lives of Iranians. But the opening was limited and short-lived. Rouhani was not able to rein in the judiciary and the intelligence ministry, which continued to arrest human rights activists, lawyers, journalists, artists, and political dissidents.

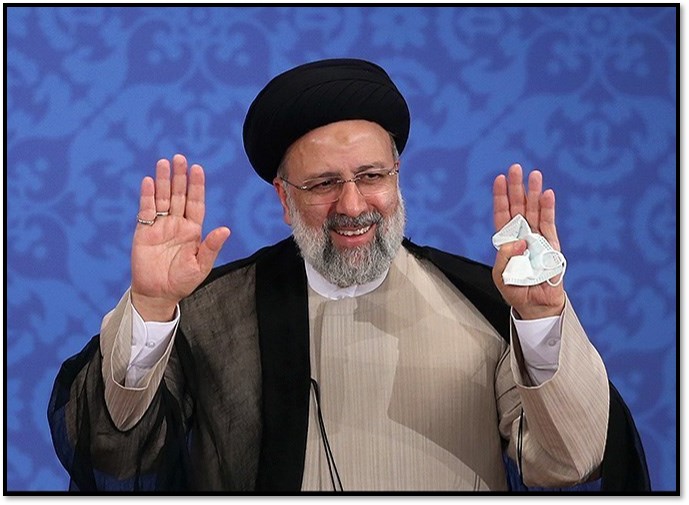

The Guardian Council’s extreme vetting of candidates in the 2021 presidential election clearly demonstrated how narrow the political space has become. The 12-man panel of jurists barred several prominent politicians, including then Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri, former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and former Speaker of Parliament Ali Larijani. Only seven out of nearly 600 candidates were cleared to run. And five out of the seven were conservatives.

Nonetheless, the political discourse in the public sphere remains vibrant. For example, the press has a relatively high degree of freedom for a semi-authoritarian state. Not all the conservative elements of the state necessarily want to shut down the entire political space. Some may even want to open it up to help overcome at least some of the legitimacy deficit. The authorities are most concerned about organized political opposition and mass protests. Cleary, the two broad political camps cannot eliminate each other. Despite the consolidation of power by the conservatives, political contestation seems to constraint the deep state’s ability to totally close the political field.

Which faction is dominant in 2022? And how strong is the opposition?

The principlists – conservatives committed to rigid interpretations of revolutionary principles – are the dominant faction. They control the executive branch, the judiciary and the legislature. But there are sub factions within the camp that disagree on foreign policy issues, on how to manage the economy and even on social issues. For example, after the 2021 election of Ebrahim Raisi, a hardliner, the principlists debated whether to return to the 2015 nuclear deal and under what conditions. Some powerful voices among have vehemently opposed the return to the agreement.

The reformists are disillusioned and on the sidelines. Most of them are not in government at the national or local level. They are disorganized and do not have the spirit to regroup. I would not write off the reformists, though. They have a natural advantage over the conservatives because their views are more in line with the majority of the public. For now, the reformists are biding their time and observing how the principlists perform after years of criticizing President Rouhani and his supporters.

The demand for reform is still widespread in society. So the reformists could return if the state opens up the political space again. The state could proactively open up to let off some steam, or public pressure might force an opening.

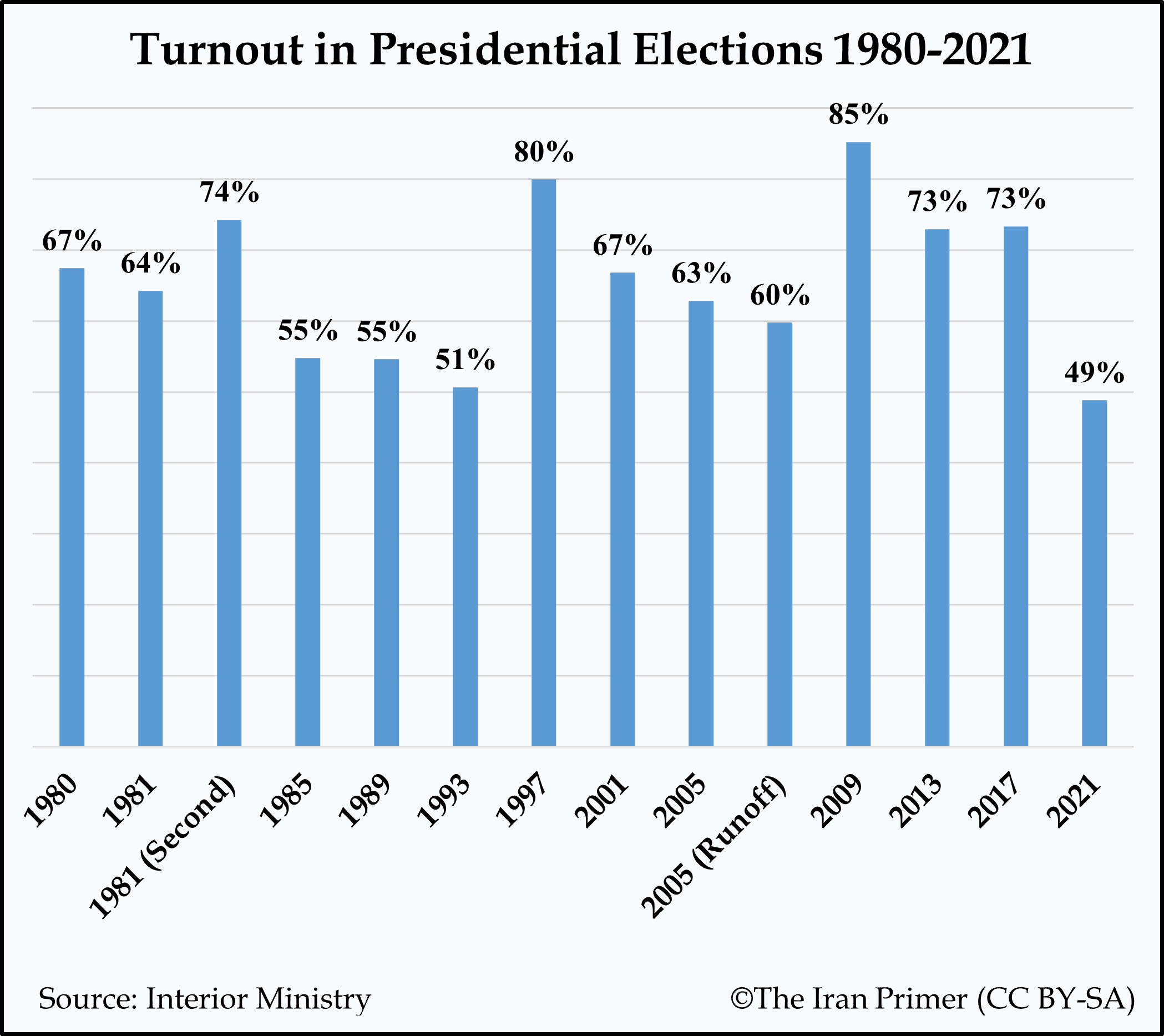

The turnout for the last presidential election – in June – was the lowest since the revolution. Does that reflect disillusionment with the election process and specific candidates, or is it a wider disillusionment with the Islamic Republic?

The turnout, 49 percent, reflected disillusion with both the Islamic Republic and the electoral process. The Guardian Council’s vetting provided an excuse for many people who were already apathetic to stay home. And the reformists lacked a coherent strategy. Some wanted to boycott, others did not, so this debate sowed confusion among the reformists’ base.

The turnout, 49 percent, reflected disillusion with both the Islamic Republic and the electoral process. The Guardian Council’s vetting provided an excuse for many people who were already apathetic to stay home. And the reformists lacked a coherent strategy. Some wanted to boycott, others did not, so this debate sowed confusion among the reformists’ base.

But those who sat out the 2021 election have not necessarily given up on elections entirely. I think that most Iranians still see the ballot box as the only way to bring reform, however limited. Each time the system opened up and the public saw an opportunity for change, the masses turned out in presidential elections. In 1997, the year Khatami won, turnout was 80 percent. In 2009, when Mousavi ran, the turnout was 85 percent. In 2013, the year Rouhani won, turnout was 73 percent.

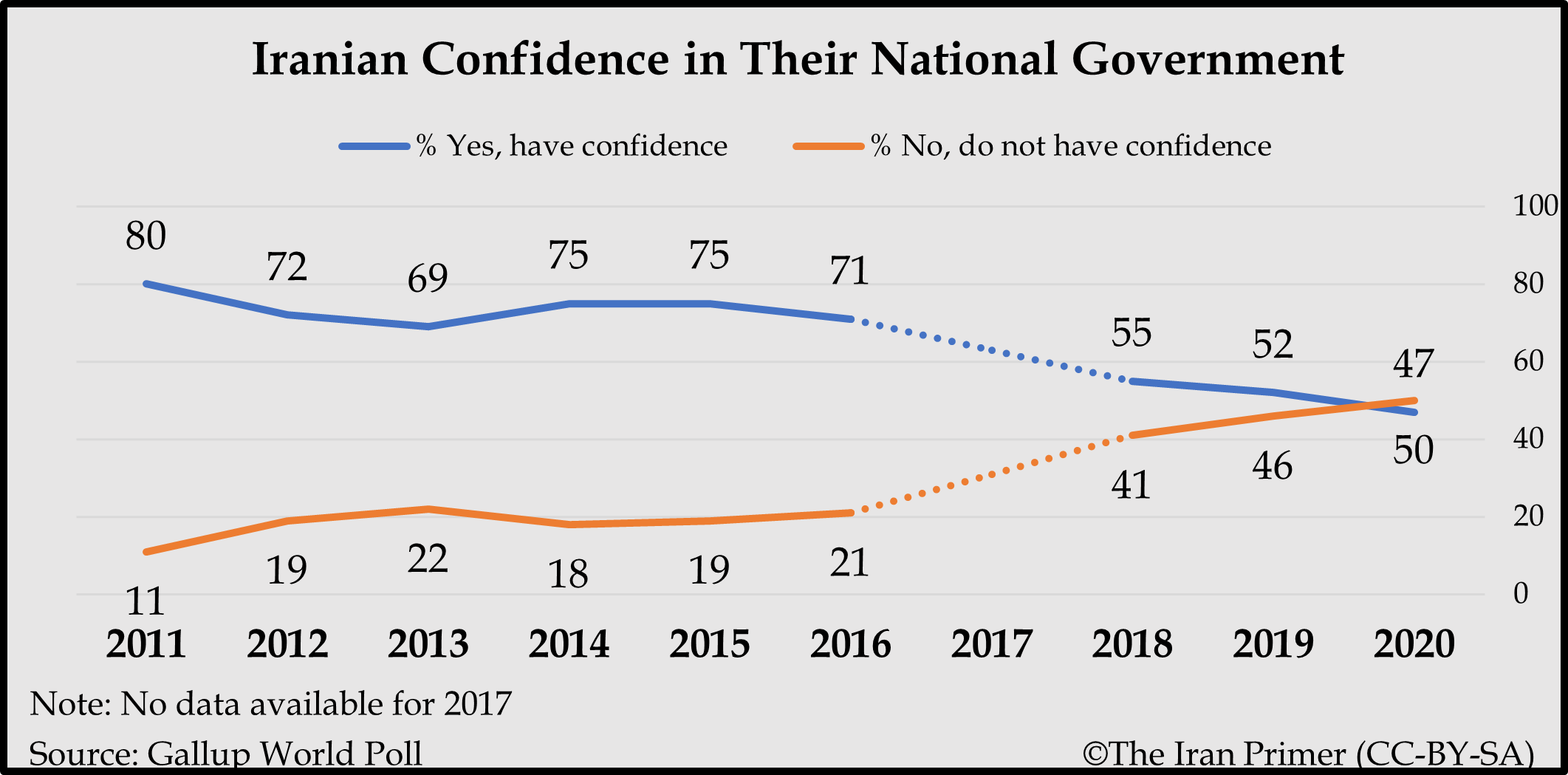

Polls show that public confidence in Iran’s government has waned. In 2011, 80 percent of Iranians had confidence in the government compared to just 47 percent in 2020, according to polling by Gallup. What might explain the decline? What are the implications for the future of the revolution?

Public confidence in government is largely a reflection of people’s own well-being. Most people tend to judge the government’s performance based on how their living standards have changed and whether their children find decent jobs.

Another issue is that the generation of leaders currently in power does not appear to have a plan for solving the myriad economic, environmental and health crises facing Iran. They do not appear to be competent compared to the first generation of revolutionaries, who had more charisma and public trust. If the system does not move to be more inclusive, mistrust of the state will probably continue to increase.

At the same time, many Iranians still have a strong sense of pride that the country has withstood so many outside pressures, from war to international sanctions. This, in part, explains why a slight majority still had confidence in the government in 2020. And, of course, a minority of the population buys into the state’s ideology and has a lot of confidence in the government.

How have the original revolutionaries, including Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, planned for a transition to a younger generation?

For years, Khamenei has been pushing for a transition to a younger generation. He wants the youth to learn from seasoned bureaucrats. At the same time, the old guard has been retiring or passing away. So, the transition is already happening.

Raisi’s election and the confirmation of his cabinet was a significant indicator of the generational shift. Khamenei was born in 1939 whereas Raisi was born in 1960. And Raisi’s cabinet members, on average, are nearly a decade younger. Many were children or teenagers during the 1979 revolution. Ehsan Khandoozi, the finance minister, was born in 1980.

Iran’s population is now dominated by a post-revolution generation born in the 1980s. What are this generation’s demands? How do they deviate from the revolution’s early goals? Is the regime able or willing to satisfy them?

Many members of the generations born after 1979 do not identify with the experiences of the revolution. And their identities were not forged during the hardship of the Iran-Iraq War either. Their primary concerns are economic. The younger ones, who have grown up with the internet and feel connected to the outside world, have a different set of priorities than the old guard. Those between age 25 and 38, by and large, want good-paying jobs, the ability to travel abroad and to be part of the entrepreneurial culture in Iran. They are interested in social activism and are less into politics.

Only a minority of young Iranians, maybe 10 to 15 percent, are very committed to the religious and conservative worldview propagated by the state. They live in a completely different galaxy than their peers. They have different interests and priorities. The polarization between conservative and liberal youth in 2022 is much deeper than in 1979.

This generation could become problematic for the system. On the one hand, the youth could become silent soldiers of the state if they are satisfied with their standard of living. On the other hand, if the economy deteriorates, they have the potential to free ride onto a mass anti-government movement.