Michael Elleman is Director of Non-Proliferation and Nuclear Policy at the International Institute for Strategic Studies and a former U.N. weapons inspector, is the principal author of “Iran's Ballistic Missile Capabilities: A Net Assessment.”

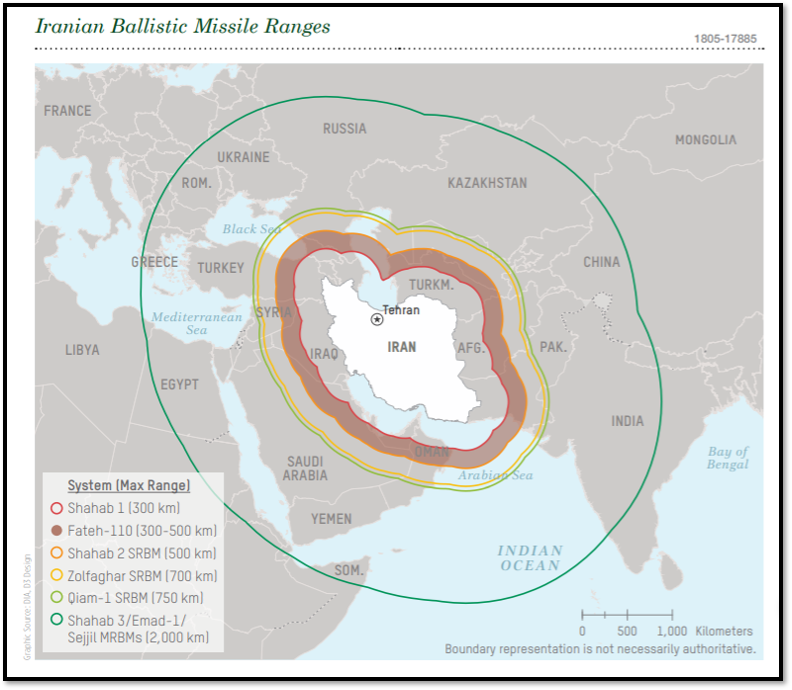

- Iran has the largest and most diverse ballistic missile arsenal in the Middle East. (Israel has more capable ballistic missiles, but fewer in number and type.) Most were acquired from foreign sources, notably North Korea. The Islamic Republic is the only country to develop a 2,000-km missile without first having a nuclear weapons capability.

- Iran is still dependent on foreign suppliers for some key ingredients, components and equipment, but it has the technical and industrial capacity to develop long-range missiles, including an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile, or ICBM.

- The military utility of Iran’s liquid-fuel ballistic missiles is limited because of poor accuracy, so these missiles are not likely to be decisive if armed with conventional, chemical or biological warheads. But Tehran could use its missiles as a political or psychological weapon to terrorize an adversary’s cities and pressure its government.

- Iran’s indigenous Fateh-110 family of solid-fuel missiles have achieved the precision necessary to destroy military and critical-infrastructure targets reliably, as demonstrated during its January 2020 attack against U.S. forces stationed at Ayn al Asad airbase in Iraq using Zolfaghar missiles.

- Iran should not be able to reliably strike Western Europe before 2022 or the United States before 2025—at the earliest.

- Iran’s space program, which includes the successful launch of several small, crude satellites into low earth orbit using the Safir and Qased carrier rockets, proves the country’s growing ambitions and technical prowess. Since 2016, the larger, more powerful Simorgh failed to put a satellite into orbit during four launch attempts and remains a work in progress.

Overview

Iran’s pursuit of ballistic missiles pre-dates the Islamic revolution. Ironically, the shah teamed with Israel to develop a short-range system after Washington denied his request for Lance missiles. Known as Project Flower, Iran provided the funds and Israel the technology. The monarchy also pursued nuclear technologies, suggesting an interest in a delivery system for nuclear weapons. Both programs collapsed after the revolution.

Under the shah, Iran had the largest air force in the Gulf, including more than 400 combat aircraft. But Iran’s deep-strike capability degraded rapidly after the break in ties with the West limited access to spare parts, maintenance, pilot training and advanced armaments. So Tehran turned to missiles to deal with an immediate war-time need after Iraq’s 1980 invasion. Iran acquired Soviet-made Scud-Bs, first from Libya, then from Syria and North Korea. It used these 300 km (185 miles) range missiles against Iraq from 1985 until the war ended in 1988.

Since the war, Tehran has steadily expanded its missile arsenal. It has also invested heavily in its own industries and infrastructure to lessen dependence on unreliable foreign sources. It is now able to produce its own missiles, although some key components still need to be imported. Iran has demonstrated that it can also significantly expand the range of acquired missiles, as it has done with Nodong missiles from North Korea, which it then renamed. Iran’s missiles can already hit any part of the Middle East, including Israel. Over time, Tehran has established the capacity to create missiles to address a full range of strategic objectives.

Related Material:

- Iran's Missiles: Military Strategy

- Iran's Missiles: Infographics and Photos

- Iran's Missiles: Timeline of Attacks

- Iran's Missiles: Transfer to Proxies

Iran's Expanding Arsenal

Shahab missiles: Since the late 1980s, Iran has purchased additional short- and medium-range missiles from foreign suppliers and adapted them to its strategic needs. The Shahabs, Persian for “meteors,” were long the core of Iran’s program. They use liquid fuel, which involves a time-consuming launch. They include:

The Shahab-1 is based on the Scud-B. (The Scud series was originally developed by the Soviet Union). It has a range of about 300 km (185 miles).

The Shahab-2 is based on the Scud-C. It has a range of about 500 km (310 miles). Iran is widely estimated to have between 200 and 300 Shahab-1 and Shahab-2 missiles capable of reaching targets in neighboring countries.

Iran has converted a significant portion of its Shahab-2 missiles into Qiam missiles. The Qiam uses a detachable warhead, which reduces its vulnerability to the missile defenses deployed in the region. A second version of the Qiam appears to be equipped with a maneuvering re-entry vehicle (warhead) to improve accuracy. Both versions have a range of 700 to 800 km (440 to 500 miles) when fitted with a 500 to 600 kg (1,100 to 1,300 lbs) warhead. Tehran has exported the Qiam to the Houthi rebels in Yemen for attacks on Saudi Arabia.

The Shahab-3 is based on the Nodong, which is a North Korean missile. It has a range of about 900 km (560 miles). It has a nominal payload of 1,000 kg (2,200 lbs). A modified version of the Shahab-3, renamed the Ghadr-1, began flight tests in 2004. Several variants of Ghadr-1 have emerged, each of which have been slightly modified to improve reliability and operational simplicity. Most of Iran’s Shahab-3 missiles are believed to have been converted into the Ghadr missiles. The Ghadr extends Iran’s reach to about 1,600 km (1,000 miles), which qualifies as a medium-range missile. But it carries a smaller, 750 kg (1,650 lbs) warhead.

The Emad, tested in 2015, is a modified version of the medium-range Ghadr missile. The modification includes a new nosecone, fitted with four-small winglets at the base of the warhead. Presumably, the winglets are designed to steer the warhead during re-entry into the atmosphere with the purpose of bettering accuracy. While it is not known if Iran transformed the Emad into a precision-guided missile at this time, its appearance is a clear indication of Iran’s ambitions.

The Emad’s maximum range and payload mass are difficult to determine because little is known about the on-board components that facilitate steering of the warhead during re-entry. The added mass certainly reduces the Emad’s range and payload values relative to the Ghadr, but by how much is not known. Nevertheless, its maximum range is likely less than 1,500 km.

Sajjil missiles: Sajjil means “baked clay” in Persian. These are a class of medium-range missiles that use solid fuel, which offer many strategic advantages. They are less vulnerable to preemption because the launch requires shorter preparation – minutes rather than hours. Iran is the only country to have developed missiles of this range without first having developed nuclear weapons.

This family of missiles centers on the Sajjil-2, a domestically produced surface-to-surface missile. It has a medium range of about 2,000 km (1,200 miles) when carrying a 750 kg (1,650 lbs) warhead. It was test fired in 2008 under the name, Sajjil. The Sajjil-2, which is probably a slightly modified version, began test flights in 2009. This missile would allow Iran to “target any place that threatens Iran,” according to Brig. Gen. Abdollah Araghi, a Revolutionary Guard commander.

The Sajjil-2 appears to have encountered technical issues and its full development has slowed. No known flight tests have been conducted since 2011. If Sajjil-2 flight testing resumes, the missile’s performance and reliability could be proven within a year or two. The missile, which is unlikely to become operational before 2022, is the most likely nuclear delivery vehicle—if Iran decides to develop an atomic bomb. But it would need to build a bomb small enough to fit on the top of this missile, which would be a major challenge.

The Sajjil program’s success indicates that Iran’s long-term missile acquisition plans are likely to focus on solid-fuel systems. They are more compact and easier to deploy on mobile launchers. They require less time to prepare for launch, making them less vulnerable to preemption by aircraft or other missile defense systems.

Iran could attempt to use Sajjil technologies to produce a three-stage missile capable of flying 3,700 km (2,200 miles). But it is unlikely to be developed and fielded before 2024.

Iran fields a family of increasingly accurate, short- and now medium-range, solid-fuel missiles with ranges of up to 1,000 km (625 miles), and possibly as far as 1,400 km (880 miles) according to Iranian sources. The Fateh-110, for example, flies on a trajectory that remains within the earth’s atmosphere during its entire flight. Small winglets mounted just below the warhead section can thus steer the rocket to its target with greater precision. In principle, the Fateh-110, or its variants, Khalij-Fars and Hormuz, could be accurate enough to strike point-targets reliably.

Since the early 2010s, Iran has incorporated a series of structural and guidance modifications to improve the range and accuracy of the Fateh-110. The original Fateh-110A’s range of about 200 km (124 miles) has grown to roughly 500 km (310 miles), with the introduction of the Fateh-313. The Fateh Mobin includes an electro-optical seeker to further enhance missile accuracy. The Fateh-type missiles carry payloads of about 450 kg (990 lbs).

Zolfaghar, Dezful, and Haj Qasem Soleimani employ the same basic design principles of the Fateh-type systems but have slightly larger-diameter rocket motors that propel them to longer ranges, approximately 700, 1,000 and 1,400 km, respectively (440, 625 and 880 miles). The larger missiles are believed to carry warheads of about 550 kg (1,212 lbs). The January 2020 missile attack on the Ayn al Asad airbase in Iraq demonstrated Iran’s mastery of precision guidance technologies, as a majority of the Zolfaghar missiles struck key targets. Fateh-313s and Qiam-1s may have been used as well.

These solid-fuel missiles are battlefield weapons possessing considerable warfighting capacity because of their accuracy. Iran has a variety of drones capable of collecting and supplying target data for its precision-guided missiles. It remains unclear if Iran has the robust and secure communications network needed to enable real-time targeting.

However, it is significant to note that the satellite navigation units, such as Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) receivers, employed by Iran’s precision-guided missiles can be rendered less-effective by jamming or spoofing GPS signals, a capability that Tehran’s technologically superior adversaries possess.

Although the 2010s were marked by Iran’s prioritization of the development of precision-guided missiles to enhance their military utility over the creation of longer-range missiles, as evidenced by the emergence of the Fateh, Zolfaghar, Dezful and Haj Soleimani systems described above, it has not abandoned its pursuit of longer-range missiles. Iran flight tested, without success, the Khorramshar missile in January 2017, although there is some reporting to suggest a test launch was conducted in 2016 as well. Both tests reportedly failed.

The Khorramshar appears to be based on North Korea’s Hwasong-10 intermediate-range ballistic missile, or IRBM, which is in turn is a modified version of the obsolete Soviet R-27 (SS-N-6) submarine-launched ballistic missile, or SLBM. The Hwasong-10, referred to as the Musudan by U.S. intelligence, had a terrible track record when tested up to at least eight times by North Korea in 2016. All the tests failed, with one possible exception, so it is not surprising that the Iranian version is also suffering from some teething problems. Iranian officials say the Khorramshar has a maximum range of 2,000 km (1,243 miles) when carrying an 1,800 kg (3,970 lbs) warhead. When fitted with a 1,000 kg (2,200 lbs) payload, the missile should be able to reach targets at a range of almost 3,000 km (1,864 miles). A more definitive assessment of Khorramshar is only possible with additional details or flight test results.

Space Program

Iran’s ambitious space program provides engineers with critical experience developing powerful booster rockets and other skills that could be used in developing longer-range missiles, including ICBMs.

The Safir, which means “messenger” or “ambassador” in Persian, is the name of the carrier rocket that launched Iran’s first satellite into space in 2009. It demonstrated a new sophistication in multistage separation and propulsion systems.

Iran has experienced some success with the Safir. Ten known launches have occurred since 2008, with just four being deemed successful. Two attempts to use Safir to orbit a satellite in 2019 failed, one while the rocket was being prepared.

The Simorgh, which is the Persian name of a benevolent, mythical flying creature, is another carrier rocket to launch satellites. A mock-up was unveiled in 2010. It’s first stage is powered by a cluster of four Shahab-3/Nodong engines and a low-thrust second stage the relies on the steering engines original used by the obsolete Soviet R-27 SLBM. Simorgh has failed all four attempts to orbit a satellite since 2016.

The Simorgh is optimized for satellite launches and is largely unsuitable for use as a ballistic missile. An ICBM based on Simorgh technology would be very large and cumbersome to deploy as a military system. If Iran opted to transform its Simorgh into an ICBM, it would take a handful of years, and would not likely become operational before 2023 or 2024. Without substantial modifications, the Simorgh could not reach the U.S. mainland, but could threaten all of Western Europe. No country has ever converted a liquid-fueled satellite launcher into a long-range missile, primarily because the differing operational requirements make the transformation impractical.

In April 2020, the IRGC- Aerospace forces launched a satellite using a new carrier rocket, known as Qased. The reconnaissance satellite was successfully lifted into orbit and has been producing low-resolution imagery of terrestrial targets of interest. Qased relies on a Ghadr missile for its first stage, and is topped by two small, solid-fuel stages. Its performance parameters are roughly equivalent to the Safir but has greater growth potential. The IRGC-Aerospace forces assert that the next satellite launch will be done using an all-solid fuel booster configuration, suggesting that the Ghadr will be replaced by a large, solid-fuel motor like Sajjil-2’s first stage motor, but longer and more powerful. In principle, an all solid-fuel carrier rocket could be more easily transformed into a long-range ballistic missile.

Factoids

- Iran’s universities and other technical centers continue to conduct basic and applied research in support of the missile and space launcher development programs.

- As Iran continues to increase the range of its precision-guided, solid-fuel Fateh-family of missiles, its stockpile of inaccurate Scud-based, liquid-fuel missiles will become increasingly obsolete.

- U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231 forbids Iran from activities involving “missiles designed to be nuclear capable.” According to a 2019 study, only the original Shahab-3 and Khorramshar missiles are clearly “designed to be nuclear capable.”*

- Iran has dedicated considerable resources to enhancing the pre-launch survivability of its ballistic missile forces through increased mobility and a growing network of underground bunkers and tunnels from which missiles can be launched.

Overcoming Limitations

Iran’s liquid-fuel ballistic missiles have poor accuracy. The successful destruction of a fixed military target, for example, would probably require Iran to use a significant percentage of its liquid-fuel missile inventory. Against large military targets, such as an airfield or seaport, Iran could conduct harassment attacks aimed at disrupting operations or damaging fuel-storage depots. But the missiles would probably be unable to shut down critical military activities. The number of transporter-erector-launchers (TELs) available and the delays to reload them would also limit the impact of even a massive attack.

Without a nuclear warhead, Iran’s liquid-fuel ballistic missiles are likely to be more effective as a political tool to intimidate or terrorize an adversary’s urban areas, increasing pressure for resolution or concessions. Such attacks might trigger fear, but the casualties would probably be low – probably fewer than a few hundred, even if Iran unleashed its entire ballistic missile arsenal and a majority succeeded in penetrating missile defenses.

However, the growing sophistication and precision of its solid-fuel, Fateh-family of missiles enables Iran to destroy reliably stationary military targets throughout the region. This newly development military capability has been demonstrated on several occasions over the past three years, including:

- June 2017: Medium-range ballistic missiles launched near Deir Ezzor against ISIS

- September 2018: Seven Fateh-110s launched against Kurdish opposition parties in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

- October 2018: Medium-range ballistic missiles launched against ISIS in Iraq and Syria

- September 2019: UAVs and cruise missiles launched against Saudi Arabian oil facilities

- January 2020: Up to 22 missiles launched at two Iraqi bases housing U.S. troops

Trend Lines

- Iran will likely continue to enhance the precision and increase the range of its solid-fuel, Fateh-family of ballistic missiles, while also seeking to improve pre-launch survivability. In parallel, Tehran is likely to build a capacity to develop real-time targeting using uncrewed aerial vehicles and drones.

- Iran’s advanced engineering capabilities and commitment to missile and space launcher programs are likely, over time, to lead to development of additional missile systems. Export controls will slow, but not stop progress.

- There is no strong evidence that Iran is actively developing an intercontinental ballistic missile. However, Iran has the technical and industrial wherewithal, and likely already possesses key hardware required develop and field an ICBM if a decision is made to do so. The new system can’t be deployed out of the blue. If Iran decides to pursue an ICBM capability, the necessary flight testing will provide two-to-five years of advanced notice.

Michael Elleman, Director of Non-Proliferation and Nuclear Policy at the International Institute for Strategic Studies and a former U.N. weapons inspector, is the principal author of “Iran's Ballistic Missile Capabilities: A Net Assessment.”

*See, Michael Elleman and Mark Fitzpatrick, “Evaluating design intent in Iran's ballistic-missile programme,” Chapter 3, pp. 89-130, in: Mark Fitzpatrick, Michael Elleman and Paulina Izewicz in Uncertain Future: The JCPOA and Iran’s nuclear and missile programmes, Adelphi Series; London : Routledge for The International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2019.