By Robin Wright and Garrett Nada

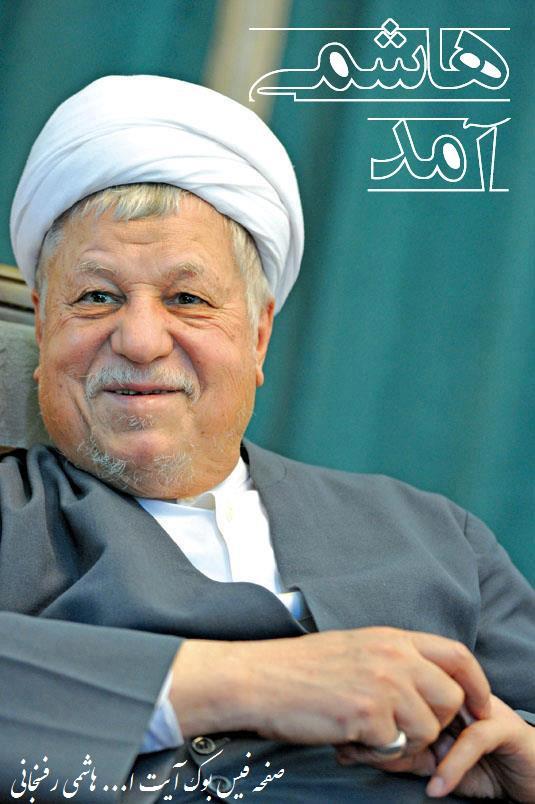

Among the 680-plus candidates who registered to run for president of Iran, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani stands alone as the most experienced and savviest politico — by far. He has almost done it all.

He was speaker of parliament for nine terms in the 1980s. He was president for two terms from 1989 to 1997. He was chairman of the Assembly of Experts, a panel of more than 80 clerics and scholars who oversee the supreme leader, from 2007 to 2011. And he is currently chief of the Expediency Council, the ultimate arbiter of disputes between parliament and the 12-man Guardian Council.

He was speaker of parliament for nine terms in the 1980s. He was president for two terms from 1989 to 1997. He was chairman of the Assembly of Experts, a panel of more than 80 clerics and scholars who oversee the supreme leader, from 2007 to 2011. And he is currently chief of the Expediency Council, the ultimate arbiter of disputes between parliament and the 12-man Guardian Council.

But more than titles, Rafsanjani was long the behind-the-scene powerbroker in the world’s only modern theocracy. He orchestrated the rewriting of the constitution in 1989 to create an executive president — and then got himself elected to the more powerful post. The same year, he mobilized the inner circle after the death of revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini to support Ali Khamenei as the new supreme leader. The twin steps are still the biggest political overhaul since the 1979 revolution.

For his wiliness, Rafsanjani was nicknamed “the shark,” which is also a play on his smooth beardless chin, a physical attribute inherited from Mongolian ancestors. He was also — somewhat cynically — nicknamed “Akbar Shah,” a dig at the king-like power he once wielded. His Cheshire cat grin was a staple of Iranian politics in the 1980s and 1990s — and a barometer of who and what was in favor.

Yet Rafsanjani has struggled since 2000 to retain his leverage. Subsequent comeback efforts have failed.

His famous family has also increasingly been targeted by both the regime and his political rivals. Two of his children were charged with acting against the regime after the disputed 2009 presidential election. His daughter Faezeh Hashemi ― a former member of parliament and vice president of Iran’s Olympic committee ― spent six months in prison for “spreading propaganda.” She was released in March 2013. His son, Mehdi Hashemi was jailed for more than two months in late 2012 for inciting unrest and still faces formal prosecution.

What support does Rafsanjani have among the general population today?

After two decades of dominating political power, Rafsanjani suffered serious setbacks in his last two campaigns for parliament in 2000 and the presidency in 2005. Although considered a pragmatist in the 1980s and early 1990s, a new generation of reformists began turning elsewhere in the late 1990s. Disillusionment deepened after his statements following the brutal government crackdown on protests in 1999, when university students rallied against the closing of a reformist newspaper and new limits on freedom of expression. In a sermon, Rafsanjani condoned the use of force to stop “enemies of the revolution.”

In the 2000 election, Rafsanjani failed to win enough votes for any of the 30 parliamentary seats allocated to Tehran — a stunning development. A recount later claimed that he came in 29th, although he opted not to take the seat.

Rafsanjani attempted another comeback in a run for the presidency in 2005. His inventive campaign had young girls on rollerblades pass out “Hashemi 2005” bumper stickers. The campaign set up tents in Tehran and blared Western-style music ― a controversial move in a country that had banned broadcast music after the 1979 revolution. Rafsanjani faced Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the working-class mayor of Tehran, in a runoff election. Ahmadinejad routed Rafsanjani with about 62 percent of the vote.

How is Rafsanjani perceived among Iran’s political elite?

Key members of the reformist elite supported Rafsanjani’s 2013 presidential bid. Former President Mohammad Khatami (left) called Rafsanjani the “most appropriate figure” for easing economic challenges and international pressures. “Now it is the people's turn to enter the scene with bravery and responsibility and assist him,” Khatami said.

But hardliners countered by painting Rafsanjani as part of a “deviant camp.” They claimed that he helped incite mass demonstrations—the largest since the revolution—after the disputed 2009 presidential election. Rafsanjani’s critics demanded that he condemn Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, leaders of the opposition Green Movement who both ran for president in 2009.

In May 2013, some 100 hardline members of parliament reportedly sent a petition to the 12-man Guardian Council urging it to disqualify Rafsanjani for having a major role “in managing the sedition” after the 2009 election. Before the election, hardliners had also considered a new law prohibiting candidates over the age of 75. The idea was widely believed to be an attempt to prevent Rafsanjani, then 78, from running. But the Guardian Council rejected the bill.

What is Rafsanjani’s record on domestic policy?

In the 1980s and 1990s, Rafsanjani was considered pragmatic on both domestic and foreign affairs. After the eight-year war with Iraq, he moved to jumpstart the war-ravaged economy. He pushed a free-market agenda after he became president in 1989. He reopened the stock market launched during the monarchy and encouraged foreign investment with new incentives. He cut a few subsidies and started privatizing state-run businesses.

But conservative opponents in parliament balked at his plans for economic shock therapy. And excessive spending depleted foreign exchange reserves, forcing Iran into debt. When he ran for reelection in 1993, the public also seemed less enthusiastic, as his support at the polls dropped significantly. Inflation soared in 1994, and the economy went into a recession. Iran’s Chamber of Commerce acknowledged that up to 40 percent of Iranians lived below the poverty line in 1996.

Rafsanjani initially succeeded in easing social restrictions and cultural censorship. Women began wearing brightly colored headscarves instead of the full-body and typically black chador. His minister of culture, Mohammad Khatami, was credited with allowing revival of Iranian music and cinema. But hardliners in parliament forced Khatami from office in 1992. Rafsanjani also found it increasingly difficult to enact reforms as Supreme Leader Khamenei and his conservative allies consolidated power in the mid-1990s.

What is Rafsanjani’s record on foreign policy?

In the mid-1980s, Rafsanjani reportedly played a key role in the arms-for-hostage scandal, which involved acquiring American weapons in exchange for release of American hostages held in Lebanon. He was widely viewed as the leading advocate of repairing relations with the United States to end Iran’s isolation. Even after the scandal was revealed, he reportedly dispatched a nephew to Washington to probe the potential of reviving behind-the-scenes talks.

In 1988, Rafsanjani also played a key role in convincing Ayatollah Khomeini to end the war with Iraq, in which more than 120,000 Iranians died. Afterwards, he again sought to end Iran’s diplomatic isolation. But he made little progress, partly because of Ayatollah Khomeini’s 1989 fatwa calling for the death of British author Salman Rushdie for his book “The Satanic Verses.” Tehran also continued to support Hezbollah, a radical Lebanese Shiite militia, and opposed the Arab-Israeli peace process. But Rafsanjani did improve relations with China, Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Toward the end of his presidency in the mid-1990s, Rafsanjani reportedly orchestrated the offer of a $1 billion contract to U.S. oil company Conoco to develop Iran’s offshore fields. The move was widely interpreted as an indirect overture to the United States through commercial channels. Under congressional pressure, however, President Clinton issued an executive order in March 1995 that prohibited U.S. trade in or development of Iranian oil.

What is Rafsanjani’s relationship with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei?

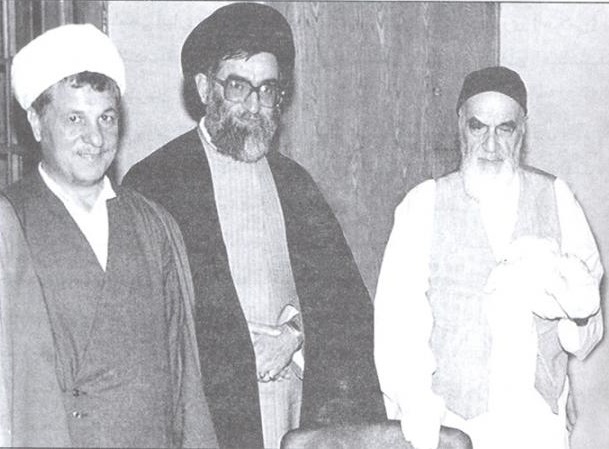

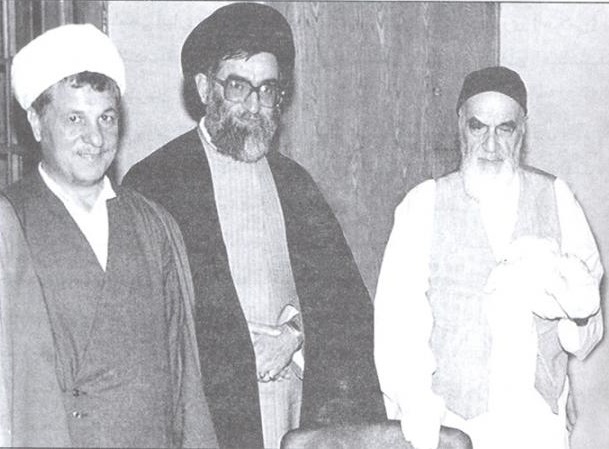

Rafsanjani and Khamenei both were active against the monarchy. Both spent time in the shah’s jail. And both were close disciples of late revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini. (The three clerics are pictured on the left in the 1980s). Rafsanjani was instrumental in promoting Khamenei to the position of supreme leader in 1989.

But Rafsanjani’s relationship with Khamenei soured in the 1990s as the two men jockeyed for control of the Islamic Republic. As the new supreme leader, Khamenei reportedly disapproved of Rafsanjani’s efforts to improve relations with the West, move towards a free-market economy, and loosen social restrictions. Rafsanjani also then had wider popular support.

Khamenei gradually got the upper hand after Rafsanjani had to step down from the presidency in 1997, as the constitution only allows two sequential terms. Rafsanjani’s attempts at a political comeback in 2000 and 2005 then failed.

After the controversial 2009 presidential election, the regime also revoked Rafsanjani’s title as Friday prayer leader when he gave a sermon criticizing the government crackdown on protestors. Rafsanjani then lost his post as head of the Assembly of Experts in 2011. Ayatollah Mohammad-Reza Mahdavi Kani, an elderly conservative cleric who reportedly had Khamenei’s backing, took his place. Rafsanjani chose not to contest the election.

His third attempt at a comeback in 2013 surprised even astute political analysts in Iran. Rafsanjani had initially said that he would not run for president without the supreme leader’s permission. He reportedly informed the supreme leader of his interest shortly before registering—also in the final minutes of the five-day process. He did not indicate whether or not he won Khamenei’s approval.

What positions has Rafsanjani taken on Iran’s most critical domestic and foreign policy issues, such as negotiations over the nuclear program?

Rafsanjani is generally running on his past record. His official campaign website says Iran needs a “captain,” not an “inexperienced boatman” to lead Iran. He has also compared Iran’s problems in 2013 to the challenges it faced during post-war reconstruction in the 1990s.

On the economy, Rafsanjani has called for further privatization of Iran’s large state-run sector. He has also criticized the government’s reliance on oil revenues and neglect of the manufacturing and agricultural sectors. Rafsanjani has favored subsidy reform but has emphasized the importance of reinvesting government savings.

On the controversial nuclear program, Rafsanjani has supported negotiations with the West and the international community. He has also been a staunch defender of Iran’s right to peaceful nuclear technology, including uranium enrichment capabilities. Rafsanjani has said that Tehran does not want nuclear arms.

In the past, Rafsanjani advocated rapprochement with the United States and the West. Iran would negotiate with the United States if it showed “goodwill,” Rafsanjani told USA Today in 2005. In comments posted on his 2013 campaign website, he said, “We shouldn’t be afraid of interaction with the world.” At the same time, he has warned against giving into the demands of “bullying and domineering powers.”

Rafsanjani has also supported opening up Iranian society. He has called for greater media freedom and the release of detained journalists. “We should open the doors to debates,” Rafsanjani said in a July 2009 sermon after the presidential election. He has even reportedly described Facebook and other social media as a “blessing” that helps “movements against tyranny and oppression.”

Rafsanjani has publicly opposed harsh implementation of Iran’s penal code, which is based on a strict interpretation of Islamic law. “We should live based on Islamic laws and not based on radical individuals' interpretations which sometimes make people's lives difficult,” Rafsanjani told journalists in May 2005. But he was also in power during periods when the international community criticized Iran for support of extremist movements and ruthless internal repression.

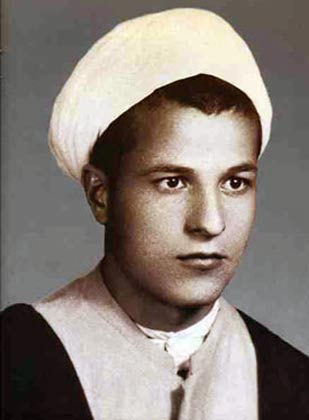

What is his background?

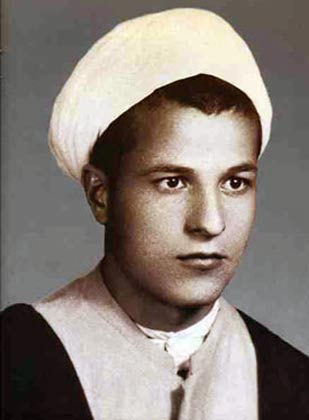

Rafsanjani was born in 1934 in Bahraman village near the south-central city of Rafsanjan, the district from which he gets his name. His father was a well-to-do pistachio farmer. Rafsanjani left home at age 14 to study Islamic jurisprudence in the holy city of Qom, where he developed a close relationship with Ayatollah Khomeini. In 1958, Rafsanjani married Effat Marashi, the daughter of a respected cleric. They have five children: Fatemeh, Mohsen, Faezeh, Mehdi and Yasser.

Rafsanjani joined the struggle against the Pahlavi dynasty in the late 1950s. He was detained seven times and imprisoned for a total of four years spread out between from 1958 to 1979, according to his bio.

Rafsanjani was a top adviser to Khomeini throughout the revolution. He was elected speaker of Iran’s first post-revolution parliament in 1980 and held the position for nine years.

Rafsanjani was a top adviser to Khomeini throughout the revolution. He was elected speaker of Iran’s first post-revolution parliament in 1980 and held the position for nine years. Khomeini appointed Rafsanjani to be his personal representative on the Supreme Defense Council during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. He also briefly served as acting commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

But he also has enemies. In May 1979, he narrowly escaped assassination by members of the leftist Islamic group, Forqan.

Rafsanjani and his family have reportedly amassed significant wealth since the revolution. In 2003, Forbes named him as one of the “millionaire mullahs.” Critics have accused Rafsanjani and his sons of corruption. His youngest son Yasser, a businessman educated in Belgium, has run a successful export-import firm. Rafsanjani’s middle son, Mehdi, has done well financially through connections to the oil industry. He used to head a subsidiary of the National Iranian Oil Company. Rafsanjani’s oldest son Mohsen headed Tehran’s metro until he resigned in 2011.

Garrett Nada is a Program Assistant at USIP in the Center for Conflict Management.

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org

He was speaker of parliament for nine terms in the 1980s. He was president for two terms from 1989 to 1997. He was chairman of the Assembly of Experts, a panel of more than 80 clerics and scholars who oversee the supreme leader, from 2007 to 2011. And he is currently chief of the Expediency Council, the ultimate arbiter of disputes between parliament and the 12-man Guardian Council.

He was speaker of parliament for nine terms in the 1980s. He was president for two terms from 1989 to 1997. He was chairman of the Assembly of Experts, a panel of more than 80 clerics and scholars who oversee the supreme leader, from 2007 to 2011. And he is currently chief of the Expediency Council, the ultimate arbiter of disputes between parliament and the 12-man Guardian Council. Key members of the reformist elite supported Rafsanjani’s 2013 presidential bid. Former President Mohammad Khatami (left) called Rafsanjani the “most appropriate figure” for easing economic challenges and international pressures. “Now it is the people's turn to enter the scene with bravery and responsibility and assist him,” Khatami said.

Key members of the reformist elite supported Rafsanjani’s 2013 presidential bid. Former President Mohammad Khatami (left) called Rafsanjani the “most appropriate figure” for easing economic challenges and international pressures. “Now it is the people's turn to enter the scene with bravery and responsibility and assist him,” Khatami said. In the 1980s and 1990s, Rafsanjani was considered pragmatic on both domestic and foreign affairs. After the eight-year war with Iraq, he moved to jumpstart the war-ravaged economy. He pushed a free-market agenda after he became president in 1989. He reopened the stock market launched during the monarchy and encouraged foreign investment with new incentives. He cut a few subsidies and started privatizing state-run businesses.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Rafsanjani was considered pragmatic on both domestic and foreign affairs. After the eight-year war with Iraq, he moved to jumpstart the war-ravaged economy. He pushed a free-market agenda after he became president in 1989. He reopened the stock market launched during the monarchy and encouraged foreign investment with new incentives. He cut a few subsidies and started privatizing state-run businesses. Rafsanjani and Khamenei both were active against the monarchy. Both spent time in the shah’s jail. And both were close disciples of late revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini. (The three clerics are pictured on the left in the 1980s). Rafsanjani was instrumental in promoting Khamenei to the position of supreme leader in 1989.

Rafsanjani and Khamenei both were active against the monarchy. Both spent time in the shah’s jail. And both were close disciples of late revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini. (The three clerics are pictured on the left in the 1980s). Rafsanjani was instrumental in promoting Khamenei to the position of supreme leader in 1989. Rafsanjani was born in 1934 in Bahraman village near the south-central city of Rafsanjan, the district from which he gets his name. His father was a well-to-do pistachio farmer. Rafsanjani left home at age 14 to study Islamic jurisprudence in the holy city of Qom, where he developed a close relationship with Ayatollah Khomeini. In 1958, Rafsanjani married Effat Marashi, the daughter of a respected cleric. They have five children: Fatemeh, Mohsen, Faezeh, Mehdi and Yasser.

Rafsanjani was born in 1934 in Bahraman village near the south-central city of Rafsanjan, the district from which he gets his name. His father was a well-to-do pistachio farmer. Rafsanjani left home at age 14 to study Islamic jurisprudence in the holy city of Qom, where he developed a close relationship with Ayatollah Khomeini. In 1958, Rafsanjani married Effat Marashi, the daughter of a respected cleric. They have five children: Fatemeh, Mohsen, Faezeh, Mehdi and Yasser. Rafsanjani was a top adviser to Khomeini throughout the revolution. He was elected speaker of Iran’s first post-revolution parliament in 1980 and held the position for nine years.

Rafsanjani was a top adviser to Khomeini throughout the revolution. He was elected speaker of Iran’s first post-revolution parliament in 1980 and held the position for nine years.