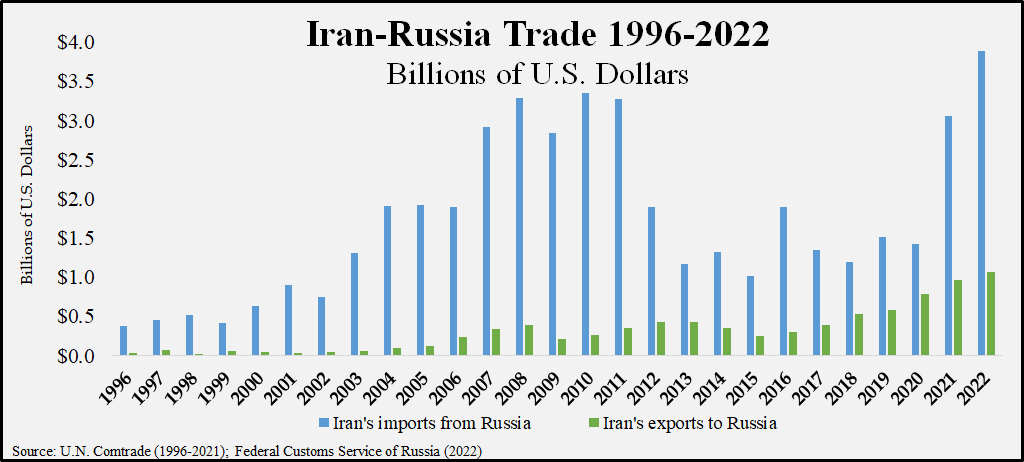

Trade between Iran and Russia fluctuated wildly in the three decades after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. It plummeted by 65 percent between 2010 and 2015 during U.N. sanctions on Iran, then nearly quadrupled by 2022 after international sanctions were lifted, a new trade route opened, and a budding military alliance deepened. “We in Iran have no limits for expanding ties with Russia,” President Ebrahim Raisi told Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2022. By 2023, trade increased further, especially with secret new military sales.

Tehran and Moscow also found common cause after being isolated by the global trading system and losing access to Western markets. Iran has faced international pressure over advances in its nuclear program since 2019, while Russia was condemned for its invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The two have become “the first and second most sanctioned countries on earth,” Alex Vatanka, director of the Iran Program at the Middle East Institute, told The Iran Primer in May 2023. “That is a big incentive for economic cooperation–because who else can they turn to? So there is common ground for new ways to pool resources.” Yet Iran couldn’t claim to have saved Russia’s economy, he said, because trade volumes were still relatively small. In 2022, Iranian trade with Russia was under $5 billion–less than a third of its $15 billion trade with China on goods excluding oil (which was Iran’s main export to China).

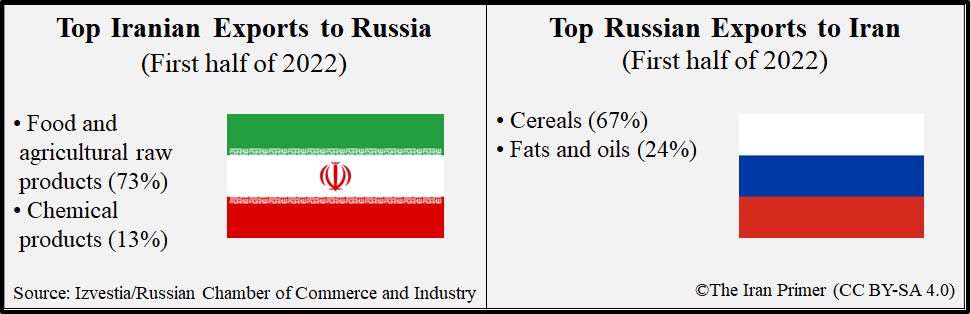

Between the mid-1990s and 2023, the trade balance between the two nations decisively favored Russia. Beginning in 2000, Iran bought largely raw materials, including iron and steel, as well as agricultural cereals, such as wheat, from Russia. In turn, Russia imported mainly fruits and nuts. Iran and Russia were among the world’s top petroleum and natural gas producers–and rivals in the international market. Oil and gas sales formed the largest source of export revenue for both countries.

By mid-2023, prospects for increasing volume in the future were still limited since neither country traded in more valuable goods that would yield larger revenues. “In terms of dollar value, Iran would have to sell a lot of agricultural goods to increase its total trade volume,” Vatanka said. “The big challenge is finding overlap where the two countries can help each other economically.”

Historically, Iran and Russia have not been natural trading partners, so they have had few deep or established business connections. In the 20th century, relations were also riven by diplomatic and military tensions. The Soviet Union occupied northern Iran during World War II and balked at withdrawing tens of thousands of troops after it ended. The standoff triggered the first crisis for the new United Nations in 1946–and planted the seeds of the Cold War. Russia also armed Saddam Hussein during Iraq’s eight-year war with Iran in the 1980s.

Under both the monarchy and the theocracy, major Iranian major companies often preferred doing business with Western partners–when the opportunities were available. “There is a lot of work that needs to be done to get the Iranian business community excited about Russia,” Vatanka explained. “It’s not going to be easy.” Trade between Iran and Russia has evolved through four phases since the Soviet demise.

Phase One: 1991–2009

The first phase of Iran-Russia trade was characterized by a slow increase followed by a boom. In the decade after the Soviet demise in 1991, trade between Tehran and Moscow was less than a billion U.S. dollars annually. It improved after Vladimir Putin became president in 2000, when he sought stronger relations with countries, such as Iran, not aligned with the West. During the first decade of the 21st century, Tehran and Moscow built a new foundation for bilateral ties and formalized a trade agreement.

President Mohammad Khatami’s visit to Moscow in 2001 – the first by a senior Iranian official since 1989–reinvigorated the relationship. Tehran and Moscow signed a broad accord (the first since the 1979 revolution) to develop trade, energy, security, science, agriculture, and public health ties. It was extended three times, each for five years.

Iran and Russia also pledged to resolve ownership disputes over oil and natural gas reserves in the Caspian Sea claimed by both countries. And they committed to boosting military and nuclear cooperation by increasing arms sales and completing construction of the Bushehr nuclear reactor to create an alternative for Iran’s energy needs.

Russia was interested in bilateral trade for both economic and political reasons, Putin said in 2001. “Iran must be an independent, self-sufficient state capable of defending its national interests.” By 2003, overall trade shot up to $1.4 billion, driven largely by Iran’s imports, two-thirds of which were iron and steel products. Trade increased over the next three years to roughly $2 billion in 2006–Iran mainly exported nuts, fruit, and cars to Russia while importing iron, steel, fuel, and wood.

In 2007, Putin visited Iran and met with President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on the sidelines of a summit of Caspian Sea leaders. (The trip was the first by a Soviet or Russian leader to Tehran since the 1979 revolution.) “In the same way that an independent Iran would benefit Russia, a powerful Russia would also benefit Iran,” Khamenei told Putin. Ahmadinejad told reporters, “Russia’s power is our power and vice versa,” In 2009, trade surpassed $3 billion–Iran still largely imported iron and steel products while exporting nuts and fruits.

Phase Two: 2010-2015

During the second phase between 2010 and 2015, trade plummeted by 65 percent to roughly $1.3 billion, largely because of international sanctions on Iran over its nuclear program. Russia was initially reluctant to support U.N. sanctions, but eventually backed Security Council Resolution 1929 in 2010 to pressure Iran into accepting diplomatic intervention. Under U.S. and E.U. pressure, the world’s major financial institution–known as SWIFT, or the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications–cut off Iranian banks in 2012, which complicated transactions between Iranian and Russian businesses.

The second phase ended in mid-2015, when Iran and the world’s six major powers–Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia, and the United States–reached a landmark accord. Tehran significantly curbed its nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. The deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), allowed Iran to boost trade again with Russia.

Phase Three: 2016-2021

The JCPOA went into effect in January 2016, marking the beginning of a third phase as trade initially soared, and then stagnated amid logistical and financial obstacles. Iran’s annual trade with Russia jumped by 72 percent to $2.2 billion in 2016. Iran primarily exported food, including fruits and vegetables more scarce in Russia. Cucumbers alone accounted for nearly 20 percent of exports. Iran imported navigation equipment and grains that it didn’t produce enough of at home. It also imported radio navigation equipment, radar, grains, munitions, and metals.

But then commerce declined, hovering between $1.7 billion in 2017 and $2.2 billion in 2020. Trade was complicated by limited shipping capacities and disputes over currency transactions, including fees to convert currencies, according to Asadollah Asgaroladi, the Iranian chairman of the Iran-Russia Chamber of Commerce. New sanctions imposed by the Trump Administration, after the U.S. withdrawal from JCPOA in 2018, made Russia and any country or company dealing with Iran liable for U.S. financial penalties.

In 2021, trade nearly doubled as Iran experienced the worst drought in 50 years–and a shortfall of some seven million tons of wheat. It imported a record four million tons from Russia. Local grain production began to recover in 2022. Iran’s imports from Russia fell 55 percent, although the Islamic Republic was still the third largest importer of Russian wheat.

Phase Four: 2022-

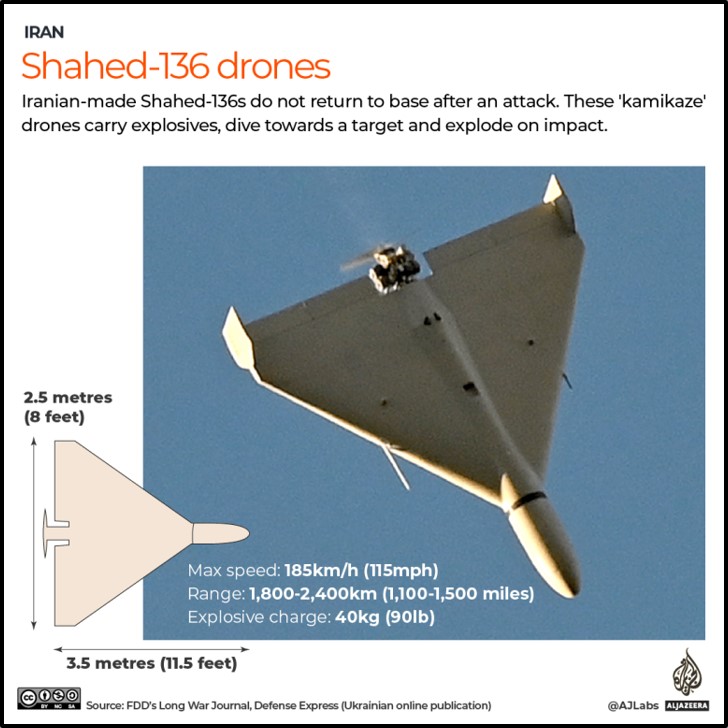

A fourth phase began in 2022, when trade–initially driven by Iranian imports–increased by nearly $1 billion to almost $5 billion. The two nations also grew closer after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, when Western nations began imposing layers of new sanctions. Trade in 2022 may have been higher, even significantly higher, as both countries denied new military sales and did not report trade data. Tehran exported more than 1,700 drones to Moscow in 2022 as it became Russia’s top military partner, the United States claimed. Iran provided relatively inexpensive suicide drones. An Iranian Shahed-186 drone cost just $20,000, a fraction of the $1 million price-tag for a Russian-made Kalibr cruise missile.

A fourth phase began in 2022, when trade–initially driven by Iranian imports–increased by nearly $1 billion to almost $5 billion. The two nations also grew closer after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, when Western nations began imposing layers of new sanctions. Trade in 2022 may have been higher, even significantly higher, as both countries denied new military sales and did not report trade data. Tehran exported more than 1,700 drones to Moscow in 2022 as it became Russia’s top military partner, the United States claimed. Iran provided relatively inexpensive suicide drones. An Iranian Shahed-186 drone cost just $20,000, a fraction of the $1 million price-tag for a Russian-made Kalibr cruise missile.

In turn, Russia reportedly offered Iran unprecedented defense cooperation on missiles, electronics and air defense. In 2023, Tehran reportedly sought to expand military cooperation by purchasing Russian fighter jets, attack helicopters, radars, and combat trainer aircraft worth billions of dollars.

In 2022, Iran and Russia pledged to negotiate a new 20-year strategic cooperation agreement to supersede the 2001 treaty. President Raisi urged “synergy” between the two nations to counter U.S. pressure during a visit to Moscow. “Just like you, we have also stood up against U.S. sanctions for 40 years.” During a reciprocal visit to Tehran in July 2022, Putin boasted of “record” growth in bilateral (non-military) trade. (The terms of the new pact were still not finalized by mid-2023.)

Moscow and Tehran also worked on developing new trade through more direct routes by land and sea to loop in energy-hungry India. Iran was “a logistic bridge in trade with the Middle East, South and southeastern Asia,” Sergey Katyrin, president of the Russian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, said in December 2022. It also had a “unique experience in surviving amid sanctions for many years.”

Russia and Iran pledged to increase commerce through the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a trade route via the Caucasus region that they had unveiled in 2000. The corridor—some 4,500 miles of railroads, highways, and shipping routes—connected Russia with Iran and India. The ambitious project faced repeated delays for two decades between 2002 and 2022, largely due to lack of investment by Russia and India.

But Moscow, facing Western sanctions over its invasion of Ukraine, suddenly showed renewed interest in the new trade corridor. In June 2022, the first shipment of goods – 41 tons of wood laminate – departed from St. Petersburg en route to the Caspian Sea Port of Anzali in Iran. It then went by road to Bandar Abbas, a port on the Persian Gulf, for shipment to Mumbai in India. The journey from St. Petersburg to Mumbai took just 24 days. The corridor helped cut transit times by roughly 40 percent. It also slashed shipping costs by 30 percent, which was a boon for Iran-Russia economic ties, according to the Federation of Freight Forwarders Associations in India. (The corridor also provided India with alternative connections to both Russia and the Central Asian countries while avoiding Pakistan, its rival and neighbor.)

Both Iranian and Russian officials predicted major trade increases within a few years. During the first seven months of 2022, container shipping across the Caspian Sea was already up 120 percent compared to 2021. “We expect that the amount of Russian cargo via all three arms of the INSTC will increase nearly twofold by 2030 from the current 17 million tons to 30 million tons,” Andrei Belouso, the first deputy Prime minister of Russia, said in October 2022. The corridor had three primary arms:

- A land-and-sea route–known as the Trans-Caspian–runs from northern Russia across the Caspian Sea to southern Iran for shipment through the Strait of Hormuz into the Arabian Sea or the Indian Ocean. It was first used in 2022.

- A rail-and-road land route–known as the Western branch–runs from northern Russia south through Azerbaijan into northern Iran and then to a southern port on the Persian Gulf for shipment again by sea. The Western branch was not complete as of mid-2023.

- The latest rail-and-road route–referred to as the Eastern branch–runs from northern Russia southeast through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to Iran for shipment to India. It was first used in 2022.

From Iran, goods can travel to India from Bandar Abbas port on the strait of Hormuz, or from the Chabahar port located further east on the Gulf of Oman.

By 2030, the North-South Corridor may be able to ship 25 million tons of freight annually, which was the equivalent to 70 percent of all global container traffic among Europe, the Persian Gulf region, and South Asia. But the corridor would still need a 102-mile rail connection between the Iranian cities of Rasht and Astara to compete significantly with the well-known and longer route from India across the Arabian Sea to the Red Sea and through the Suez Canal route to Europe.

By the end of 2022, Russia ranked as Iran’s fifth-largest trade partner–and the largest investor in the Islamic Republic. Moscow invested $2.76 billion in Tehran during the Iranian fiscal year (from mid-March 2022 to mid-March 2023). China, in comparison, invested only $131 million in Iran the same year. And, for the first time, Russia imported more industrial goods from Iran in 2022 than Tehran imported from Moscow. Iran, however, only ranked as Russia’s 16th largest partner.

Iran predicted a booming future. In June 2022, Oil Minister Javad Owji projected trade–not including military–would surge from $4 billion in 2022 to as much as $40 billion by the end of 2023. But the goal may have been “unrealistic, given historically modest trade volumes, economic headwinds in both countries, and the fact that Russia and Iran produce similar goods,” Henry Rome of the Washington Institute told The Iran Primer.

Photo Credits: Putin and Raisi via President.ir