Iran’s higher education institutions no longer enjoy any meaningful degree of academic freedom, according to a wide-ranging report by Amnesty International. The security and intelligence apparatus has gradually taken control of universities, colleges and institutes since Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected president in 2005. His administration encouraged “Islamicization” of universities. Academics who were considered too Western or secular were dismissed and student activists were expelled or suspended. “This process then accelerated and intensified in the wake of the mass peaceful protests that punctuated the second half of 2009 when millions of Iranians took to the streets of Tehran and other cities to protest against President Ahmadinejad’s disputed re-election in June 2009,” according to the report.

President Hassan Rouhani, who took office in August 2013, has only made marginal progress in opening up higher education so far. His appointment of Ja’far Tofighi as interim minister of science allowed some banned students and academics to return to higher education. The Ministry of Science announced that 126 students were allowed to resume their studies in August 2013. But hundreds more have not seen a change in their status. The following are excerpts from the report with a link to the full text.

President Hassan Rouhani, who took office in August 2013, has only made marginal progress in opening up higher education so far. His appointment of Ja’far Tofighi as interim minister of science allowed some banned students and academics to return to higher education. The Ministry of Science announced that 126 students were allowed to resume their studies in August 2013. But hundreds more have not seen a change in their status. The following are excerpts from the report with a link to the full text.

Since Hassan Rouhani’s election, most media and diplomatic attention has focused on the development of international negotiations relating to Iran’s nuclear programme and their progress. As yet, it still remains uncertain whether, and to what extent, the Rouhani presidency will see a significant reduction in tension and relaxation of the international trade, financial and other sanctions that have impacted Iran’s economy, reduced living standards and Iranians’ access to imported goods. Important though these issues are, however, they should not overshadow other problems that President Rouhani must confront if his government is to overcome the legacy of social, political and economic malaise under President Ahmadinejad and address the aspirations of its burgeoning population, more than half of which is aged under 24, with more than one quarter aged under 15.

One of the most pressing of these challenges is to be found in Iran’s universities and other institutions of higher education, including medical schools, institutes of technology and community colleges. These institutions have a student population that numbers several million annually, with women reportedly comprising around half or a little more than half, yet the higher education sector no longer enjoys any meaningful degree of academic freedom. Under President Ahmadinejad, any role that the universities had managed to retain as centres of independent thought and critical analysis, or to re-establish after the so-called Cultural Revolution of the early 1980s, was all but eviscerated as the authorities took measures to bring them under closer state control, particularly by the state security and intelligence apparatus.

This process began soon after Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was first elected President in 2005. He embarked on a new surge of “Islamicization” of the universities, in which courses deemed “western-influenced” were expunged from the curriculum, academic staff considered “secular” were dismissed or forced to retire, and student activists were expelled or suspended. At the same time, the authorities intensified gender segregation on campuses and tightened enforcement of dress and disciplinary codes for both students and teaching staff. This process then accelerated and intensified in the wake of the mass peaceful protests that punctuated the second half of 2009 when millions of Iranians took to the streets of Tehran and other cities to protest against President Ahmadinejad’s disputed re-election in June 2009.

During the protests, in which many students and academic staff participated, the universities emerged as focal points of unrest and opposition to the re-elected President and his backers within the conservative clerical and political hierarchy, including the Supreme Leader. Clearly taken aback and unnerved by the magnitude of the protests, the authorities launched a brutal crackdown of several months’ duration. Spearheaded by the Revolutionary Guards and the Basij, a paramilitary force, this succeeded in crushing the unrest through the application of a range of repressive measures, including unnecessary and excessive force; widespread arbitrary arrests and detentions; beatings, torture and other ill-treatment of detainees, several of whom died in custody, and a succession of grossly unfair “show trials” in which defendants were paraded before Revolutionary Courts before being sentenced to often lengthy prison terms. The trials were mostly held behind closed doors except for brief, televised sessions in which dozens of defendants, many of whom had been held incommunicado in extremely coercive conditions, were seen in humiliating conditions “confessing” to threatening national security and pleading for forgiveness. Scores received jail terms; some were released later before completing the full prison terms handed down in court.

Some of the university academics and students and teaching staff had been among those who joined the protests against President Ahmadinejad’s re-election. Some had openly associated themselves with the principal “opposition” presidential candidates, Mehdi Karroubi and Mir Hossein Mousavi, or joined their election campaign teams, and so were particularly targeted in the security clampdown. Others were detained during protests or while making their way to or from demonstrations.

Security forces also raided university precincts and student dormitories; allegedly causing the deaths of up to five students, and the authorities banned scores of student publications and student groups; these included the Office for the Consolidation of Unity (OCU), Iran’s largest student organization, which had branches in universities. Prior to its suppression, the OCU had spoken out to demand human rights and other reforms and urged the authorities to show greater respect for the country’s Islamic Student Associations (ISA).

Many students were released uncharged after the chastening experience of detention; some, however, were then barred temporarily or permanently from returning to their university studies. Others were charged with public order offences, or accused of committing more serious, often vaguely worded and broadly defined crimes, such as “spreading lies in order to disturb the public opinion”, “acting against national security by participating in illegal gatherings, “insulting the Supreme Leader”, or “insulting the President”. Some were accused of committing “moharebeh” (enmity against God), a capital offence. Those facing charges were tried before Revolutionary Courts, where they did not receive fair trials, and were sentenced to prison terms and, in some cases, flogging, when convicted.

Amid this new wave of persecution, thousands of students and academics left Iran, adding to the exodus of intellectual talent that has been a recurrent by-product of state repression under the Islamic Republic. Those who remained and were able to resume their higher education, returned to universities over which the authorities now assumed much closer control and imposed stricter surveillance and disciplinary regimes designed to root out and suppress any expression of dissent.

Before 2005, universities had a degree of autonomy in appointing their own deans and academic staff but the first Minister of Science appointed by President Ahmadinejad withdrew these powers from state universities and took them under the direct control of his Ministry; henceforth, the Ministry was able to ensure that not only senior level administrative positions but even junior teaching posts in the universities were made according to its own criteria, including criteria other than academic merit, such as membership of the Basij or experience within the Iranian military. With state security officials also now effectively ruling the roost, university authorities moved to chill dissent, using a system of “starring” to put student activists, and those who failed to adhere to strict dress and behaviour codes, on notice that they had were under official suspicion and under threat of disciplinary penalties, including suspension or expulsion or worse, if they should be seen to continue their perceived transgression.

Women in Higher Education

The renewed “Islamicization” process initiated under President Ahmadinejad had a gender-specific impact and came about as the number of women and girls attending university and other centres of higher education in Iran had outstripped the number of male university students. The gender segregation of campuses imposed during the Cultural Revolution of the early 1980s, which appears to have led some families to see universities as safe places for their daughters to attend, combined with the later lifting of certain restrictions on the courses available to women, contributed to a steady rise in the number of female students in higher education.

Women comprise around half, or slightly more than half, of all Iranian students in higher education. The “Islamicization” of the universities during the Cultural Revolution had many negative aspects and consequences but, somewhat ironically, the strict gender segregation of campuses that resulted from it appears to have had a positive impact in leading many families to conclude that the universities were places to which it was safe to send their daughters.

The number of women entering higher education increased progressively during the 1980s after the authorities decided to lift partially the restrictions imposed following the 1979 Islamic Revolution on women’s access to some courses. The steady rise in the number of women in higher education continued throughout the 1990s and into the first decade of the 21st century. By the academic year 2005-2006, the first under President Ahmadinejad, women were reported to comprise more than 55 per cent of the total number of students in higher education.4 In 2007, women were reported to comprise nearly 58 per cent of all students at universities and or other institutions of higher education in Iran.

Official efforts to reduce the number and proportion of female students in higher education and restore the balance in favour of men began to be implemented after President Ahmadinejad took office in 2005, although the degree to which they succeeded remains open to question. The measures included quotas which some universities imposed to limit the number of female students who could enrol on specific degree courses while other courses, such as mining engineering, which the authorities perceived as suitable only for men, were closed to female students. As well, courses such as women’s studies were reformulated away from any focus on women’s rights under international law in order to give priority attention to women’s “traditional” roles and responsibilities within the family as wives and mothers, and to emphasize “Islamic values” as the key factor determining the position of women in Iranian society, and their rules of behaviour.

Female students have told Amnesty International that, in their view, the university authorities’ stricter enforcement of dress and conduct codes, coupled with the curriculum changes and quotas limiting female enrolment in particular courses, had a disproportionate, adverse impact on women and may have deterred some girls from pursuing higher education.

Religious Minorities

Members of minority religions unrecognized by Iran’s Constitution such as Baha’is, have been largely excluded from universities since shortly after the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and thereby, in many cases, denied access to higher education. To Amnesty International’s knowledge, the Iranian authorities have never openly acknowledged such discrimination, which contravenes international law and human right treaties to which Iran is party, or sought to justify or explain it. According to unofficial sources, such discrimination is maintained under classified official guidelines.

What is clear, however, is that the exclusion of Baha’is and member of certain other religious minorities fits with the broader pattern of official discrimination against religious and ethnic minorities that are considered “un-Islamic” or of uncertain loyalty to the authorities, who deny them access to jobs in government service, freedom to exercise their religious beliefs or, in the case of ethnic minorities, use their own language as a medium of instruction in schools.

Higher Education Under President Rouhani

Against this background, the period since President Rouhani took office has seen some, albeit limited positive developments. In particular, following the appointment of Ja’far Tofighi as interim Minister of Science, the Ministry allowed some banned students and academics to return to higher education, although they had to give written undertakings as to their future conduct and activities. In September 2013, the interim Minister announced that his Ministry had established a working group that would investigate complaints from banned students and academic staff, to which he invited recently banned students to submit complaints, and said those whose complaints were upheld would be allowed to resume their studies. He said that students who had been banned before 2011 should re-take the annual university exam if they wished to return to higher education.

As yet, it is not possible to determine the impact of these measures, although the Ministry of Science said in August 2013 that 126 formerly banned students had been allowed to resume their studies. For hundreds of others, however, there appears to have been no change, and they remain barred from university either because of their peaceful exercise of freedom of expression or the rights to peaceful assembly and association, or because they are Baha’is or members of other officially unrecognized religious groups who continue to face discrimination.

President Rouhani’s first months in office have raised hopes of a less repressive system in Iran and greater government respect both for the human rights of Iran’s people and for its obligations under international human rights law. The next months and years will be crucial to whether Iran’s universities will be liberated from arbitrary interference by the security police and their political masters and be given the opportunity to become centres of independent scholarship, free thinking and innovation. Many in Iran and from around the world will be watching to see if President Rouhani seeks to address this crisis in Iranian higher education, as his pre-election oratory as an advocate of reform suggested he may, and if so with what degree of energy, resolution and ultimate success.

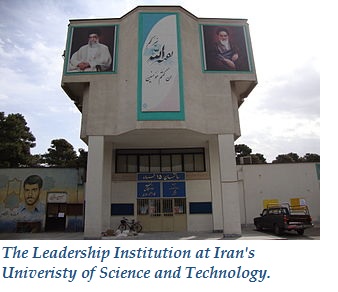

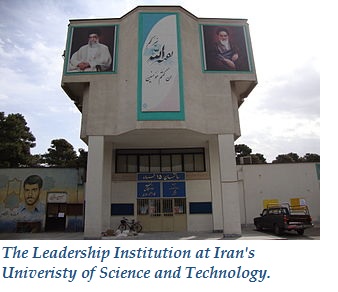

Photo credits: University of Science and Technology by Americophile (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, Isfahan University graduates by gire_3pich2005 (Own work) [FAL] via Wikimedia Commons

President Hassan Rouhani, who took office in August 2013, has only made marginal progress in opening up higher education so far. His appointment of Ja’far Tofighi as interim minister of science allowed some banned students and academics to return to higher education. The Ministry of Science announced that 126 students were allowed to resume their studies in August 2013. But hundreds more have not seen a change in their status. The following are excerpts from the report with a link to the full text.

President Hassan Rouhani, who took office in August 2013, has only made marginal progress in opening up higher education so far. His appointment of Ja’far Tofighi as interim minister of science allowed some banned students and academics to return to higher education. The Ministry of Science announced that 126 students were allowed to resume their studies in August 2013. But hundreds more have not seen a change in their status. The following are excerpts from the report with a link to the full text.  The number of women entering higher education increased progressively during the 1980s after the authorities decided to lift partially the restrictions imposed following the 1979 Islamic Revolution on women’s access to some courses. The steady rise in the number of women in higher education continued throughout the 1990s and into the first decade of the 21st century. By the academic year 2005-2006, the first under President Ahmadinejad, women were reported to comprise more than 55 per cent of the total number of students in higher education.4 In 2007, women were reported to comprise nearly 58 per cent of all students at universities and or other institutions of higher education in Iran.

The number of women entering higher education increased progressively during the 1980s after the authorities decided to lift partially the restrictions imposed following the 1979 Islamic Revolution on women’s access to some courses. The steady rise in the number of women in higher education continued throughout the 1990s and into the first decade of the 21st century. By the academic year 2005-2006, the first under President Ahmadinejad, women were reported to comprise more than 55 per cent of the total number of students in higher education.4 In 2007, women were reported to comprise nearly 58 per cent of all students at universities and or other institutions of higher education in Iran. Against this background, the period since President Rouhani took office has seen some, albeit limited positive developments. In particular, following the appointment of Ja’far Tofighi as interim Minister of Science, the Ministry allowed some banned students and academics to return to higher education, although they had to give written undertakings as to their future conduct and activities. In September 2013, the interim Minister announced that his Ministry had established a working group that would investigate complaints from banned students and academic staff, to which he invited recently banned students to submit complaints, and said those whose complaints were upheld would be allowed to resume their studies. He said that students who had been banned before 2011 should re-take the annual university exam if they wished to return to higher education.

Against this background, the period since President Rouhani took office has seen some, albeit limited positive developments. In particular, following the appointment of Ja’far Tofighi as interim Minister of Science, the Ministry allowed some banned students and academics to return to higher education, although they had to give written undertakings as to their future conduct and activities. In September 2013, the interim Minister announced that his Ministry had established a working group that would investigate complaints from banned students and academic staff, to which he invited recently banned students to submit complaints, and said those whose complaints were upheld would be allowed to resume their studies. He said that students who had been banned before 2011 should re-take the annual university exam if they wished to return to higher education.