The last and biggest hurdle to reviving the 2015 nuclear deal was the dispute between Washington and Tehran over the status of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist group. Leaders and an elite branch of the IRGC had faced several layers of economic sanctions—over support for terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, and human rights abuses—since 2007. But in 2019, President Donald Trump took a broader approach by putting the entire IRGC on the U.S. list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs), the first such step by any administration against another country’s military. The designation was part of Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign to coerce the Iranian government to renegotiate the terms and expand the subjects covered in the nuclear deal, which Trump had abandoned in 2018.

With five other world powers, the Biden Administration reengaged in diplomacy with Iran in April 2021. Most of the technical issues—what steps Iran would take to limit its program and what sanctions the United States would lift—were resolved after a year of diplomacy in Vienna. But Iran also demanded that the United States also take the IRGC off the terrorist list. Trump’s designation had been largely symbolic since the IRGC already faced dozens of sanctions. In May 2022, the Biden Administration signaled that it would keep the IRGC on the State Department FTO list.

With five other world powers, the Biden Administration reengaged in diplomacy with Iran in April 2021. Most of the technical issues—what steps Iran would take to limit its program and what sanctions the United States would lift—were resolved after a year of diplomacy in Vienna. But Iran also demanded that the United States also take the IRGC off the terrorist list. Trump’s designation had been largely symbolic since the IRGC already faced dozens of sanctions. In May 2022, the Biden Administration signaled that it would keep the IRGC on the State Department FTO list.

“We’ve made clear to Iran that if they wanted any concession on something that was unrelated to the JCPOA, like the FTO designation, we need something reciprocal from them that would address our concerns,” U.S. Special Envoy for Iran Robert Malley told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on May 25. “I think that Iran has made the decision that it’s not prepared to take the reciprocal steps. They have to decide now, are they prepared to reach a deal without extraneous demands.” As a result, Malley said, “We do not have a deal…and prospects for reaching one are, at best, tenuous.”

The U.S. Position

In March 2022, the United States reportedly offered—via European mediators—to remove the IRGC from the terrorist list in return for a public commitment from Iran to de-escalate in the region. But Tehran refused. It was only willing to provide a private letter, according to Axios.

U.S. officials downplayed the potential impact of delisting the IRGC. “In the terms of the way we think about the threat and what they do on a daily basis across the theater, I don't think much would change as a result of that [delisting],” General Frank McKenzie, the outgoing commander of U.S. Central Command, told reporters on March 18. Regardless of what happens on the IRGC issue, U.S. Special Envoy for Iran Robert Malley said, “Our view of the IRGC is many other sanctions on the IRGC will remain.”

State Department Spokesperson Ned Price noted that the FTO designation did not deter the Iranian proxies supported by the IRGC from attacking U.S. forces in Iraq. “Attacks from Iran-backed groups went up 400 percent” between 2019 and 2020—after the IRGC was listed, Price said on March 31.

General Mark Milley, the top U.S. military commander, however, said that he opposed the delisting the Qods Force, the IRGC branch responsible for foreign operations. “I believe the IRGC Quds Force to be a terrorist organization and I do not support them being delisted,” the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff told the Senate Armed Services Committee on April 7.

In Congress, both Republicans and Democrats raised concerns about removing the IRGC from the FTO list.

- On March 10, 11 House Democrats and 10 Republicans sent a letter to President Biden threatening to withhold support for a nuclear deal if the administration didn’t provide satisfactory answers to questions about the FTO designation and other issues.

- On March 17, Senator Roger Marshall (R-KS) introduced a bill to ensure that Congress would have a say in revoking FTO designations.

- On March 22, Representative Scott Frank (R-FL) and 86 House Republicans sent a letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken expressing opposition to delisting the IRGC.

- On April 4, Representatives Brian Mast (R-FL) and Scott Perry (R-PA) introduced a bill that would block the Biden administration from delisting the IRGC without congressional approval.

- On April 6, 18 House Democrats held a press conference to express their concerns about the nuclear deal. “As the Vienna negotiations come to a close, we cannot treat the FTO designation — one of our most powerful diplomatic tools used to get cold-blooded killers out of the terrorist business — as a cheap bargaining chip,” Josh Gottheimer (D-NJ) said.

- On April 26,Secretary of State Antony Blinken told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the primary sanction resulting from the FTO designation is a travel ban. He noted that the ban primarily impacts men who were conscripted into the IRGC. “The people who are the real bad guys have no intention of traveling here anyway,” Blinken said. Starting at age 18, Iranian men must complete 18 to 24 months of military service. As a result of the FTO designation, hundreds of Iranian men who served in the IRGC – including in noncombat roles – have reportedly been barred from entering the United States.

- During the hearing on April 26, Senator Todd Young (R-IN) asked Secretary Blinken to commit to not removing the FTO designation as part of a deal. “The only way I could see it being lifted is if Iran takes steps necessary to justify the lifting of that designation. So it knows what it would have to do in order to see that happen,” Blinken said.

Iran’s Demands

Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian signaled flexibility on the issue on March 26. “Senior IRGC officials have asked us to do whatever we deem necessary for national interests and not prioritize the issue of IRGC delisting,” he said in a televised interview. After facing domestic backlash from hardliners over his remarks, however, he said that Iran will not compromise or make a concession over its red lines. “I suggest re-examination of my interview yesterday,” Amir-Abdollahian wrote in an Instagram post on March 27.

Kamal Kharrazi, a senior advisor to the Supreme Leader, was blunter. The IRGC “certainly has to be removed from the list,” the former foreign minister said at the Doha Forum on March 27. “The IRGC is a national army. And a national army cannot be listed as a terrorist group.”

Kharrazi emphasized that there were other issues that needed to be resolved, including Iran’s demand for a guarantee that the United States will not withdraw from the deal a second time.

IRGC Navy Commander Alireza Tangsiri said that Iran will not forego plans to take revenge for the U.S. killing of General Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the IRGC's elite Qods Force, in exchange for the lifting of sanctions. “The enemy keeps sending messages that if we give up on avenging Soleimani, they will give us some concessions or lift some sanctions,” IRGC Navy Commander Alireza Tangsiri said on April 21. “This is pure fantasy. The Supreme Leader has emphasized the need for revenge and the Revolutionary Guards' top commander has said that revenge is inevitable and that we will choose the time and place for it.”

On May 10, E.U. coordinator Mora traveled to Tehran to work on closing remaining gaps between Iran and the United States. On the following day, he met with Ali Bagheri-Kani, Iran’s lead negotiator. E.U. foreign policy chief Borrell said that Mora’s trip had “gone better than expected” and that the JCPOA talks were “deblocked.” There is a “perspective of reaching agreement,” he told reporters on the sidelines of the G7 meeting in Germany.

On May 26, Amir-Abdollahian downplayed the IRGC dispute. “There are still remaining issues which are also important,” he told CNN's Fareed Zakaria at the World Economic Forum in Davos. The main obstacle is that Iranians fear they are not going to gain the full economic benefits of the original JCPOA.

The IRGC and Involvement in Terrorism

The IRGC was created after the 1979 revolution to protect the new Islamic state. It played a crucial role in crushing early opposition to Khomeini’s vision, but also in repelling Iraqi forces during Saddam Hussein’s invasion between 1980 and 1988. The IRGC has since functioned as the primary security force for operations at home and abroad. The IRGC has approximately 150,000 personnel. The IRGC has eclipsed the Artesh, or conventional forces. The IRGC is smaller, but it has access to more advanced weaponry and has more influence within government and the economy.

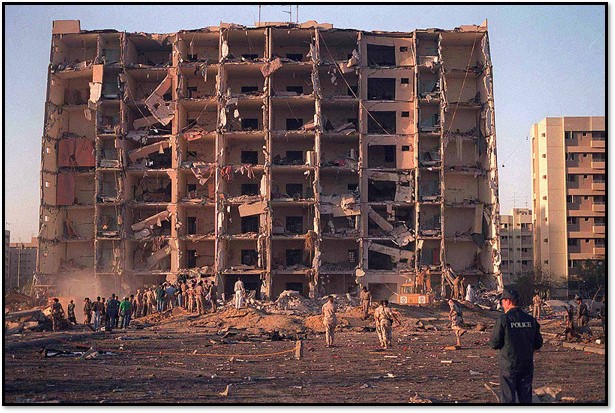

Since 1979, Iran has been implicated in assassinations, plots, and terrorist attacks in more than 40 countries, according to the State Department. The IRGC’s external operations arm, the Qods Force, has been linked to many of the operations, some of which claimed American lives. A U.S. federal court found Iran and the IRGC liable for the 1996 bombing of the Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia, which was a residential compound for U.S. military personnel; 19 Americans were killed.

The Foreign Terrorist Organization List

In 1997, the State Department initially added 30 foreign terrorist organizations to the new list. As of April 2022, it had designated 73 groups.

The IRGC is the only government military on the list. The other 72 FTOs are non-state groups, such as al Qaeda and several branches of the Islamic State. “The IRGC actively participates in, finances, and promotes terrorism as a tool of statecraft,” President Trump said in announcing the unprecedented step in 2019. “It was the “first time that the United States has ever named part of another government as a FTO,” he noted.

The State Department and the Treasury Department maintain at least four lists of terrorists, including the FTO list. The 1996 Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) authorized the Secretary of State to designate an organization as a FTO if all three conditions are met:

- The organization is foreign.

- The organization engages in terrorist activity or retains the capability and intent to engage in terrorist activity.

- The organization’s terrorist activity threatens the security of U.S. nationals or the national security (national defense, foreign relations, or the economic interests) of the United States.

U.S. law stipulates that:

- It is unlawful for a person in the United States -- or a person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States -- to knowingly provide “material support or resources” to a designated FTO.

- Foreign representatives and members of a designated FTO are barred from the U.S. and liable to be removed if already resident.

- Any U.S. financial institution that has or controls funds of a designated FTO or its agent must report it to the Treasury Department.

Delisting terrorist groups

The United States has only removed 15 groups from the FTO list. Most were delisted after disbanding. The Japanese Red Army, for example, disbanded in 2001. Others have been removed from the list after stopping terrorist activities. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) was delisted in 2021 after disarming and signing a peace agreement.

The Immigration and Nationality Act allows the Secretary of State to revoke an FTO designation at any time if:

- The basis for the designation has changed.

- It is in the interest of U.S. national security.

In February 2021, the Biden administration delisted Ansarallah, also known as the Houthis, in Yemen. Secretary of State Blinken said that the decision was prompted by “warnings from the United Nations, humanitarian groups, and bipartisan members of Congress, among others, that the designations could have a devastating impact on Yemenis’ access to basic commodities like food and fuel.”

But Washington remained “clear-eyed about Ansarallah’s malign actions,” Blinken added. He said that the three Houthi leaders designated as terrorists by the Trump administration would remain sanctioned. Similarly, if the Biden administration revoked the IRGC’s designation, it would remain sanctioned under other authorities.