Yun Sun

China is the quiet giant in the latest diplomatic campaign to prevent Iran from getting a bomb. As Tehran’s largest trading partner, Beijing has enormous political and economic leverage over the Islamic Republic. As a veto-wielding member of the United Nations, its position can also make or break any resolution. China has often followed Russia’s lead on Iran policy, but its decisions reflect independent dynamics between Beijing and Tehran that will be key to its future actions.

China is the quiet giant in the latest diplomatic campaign to prevent Iran from getting a bomb. As Tehran’s largest trading partner, Beijing has enormous political and economic leverage over the Islamic Republic. As a veto-wielding member of the United Nations, its position can also make or break any resolution. China has often followed Russia’s lead on Iran policy, but its decisions reflect independent dynamics between Beijing and Tehran that will be key to its future actions.

Arguably more than any other country, China wants to end international economic sanctions on Iran so it can increase trade. Beijing and Tehran have become increasingly important partners over the past decade. China also does not want to risk sanctions itself for doing business with Tehran, as U.S. law now stipulates.

At the height of business in 2011, China bought up to 557,000 barrels of oil per day from Iran – or almost 11 percent of its oil imports – to fuel economic growth. (In 2001, China imported 18 percent of its oil from Iran, but the volume was only 217,891 bpd, far less than in 2011.) Among key figures for 2012, according to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs:

• Sino-Iranian trade totaled $36.47 billion,

• China imported $24.86 billion worth of goods from Iran, largely crude oil and mineral oils.

• China exported $11.6 billion of goods to Iran, largely machinery, textiles and petrochemical products.

But new sanctions, particularly tough measures imposed by the United States in mid-2012, have had a major impact on the People’s Republic’s energy trade with the Islamic Republic. China’s total oil imports from Iran decreased 21 percent – from 557,000 barrels per day to 438,448 barrels per day – in 2012. Oil trade dropped another 2.2 percent in 2013 to 428,840 barrels per day.

But Beijing and Tehran still see each other as pivotal partners for the future. China is considered a key future investor in Iran’s oil and gas fields, with great potential to invest in downstream refineries to improve Iran’s outdated refining infrastructure.

China now shares the concerns of the world’s major powers about Iran’s controversial nuclear program. Beijing wants to prevent Tehran from developing the world’s deadliest weapon, which would in turn dilute China’s nuclear power status. Beijing voted for four U.N. sanctions resolutions, although it balked at subsequent more punitive measures sought by the West. Top foreign ministry officials have also participated in the Geneva talks.

China now shares the concerns of the world’s major powers about Iran’s controversial nuclear program. Beijing wants to prevent Tehran from developing the world’s deadliest weapon, which would in turn dilute China’s nuclear power status. Beijing voted for four U.N. sanctions resolutions, although it balked at subsequent more punitive measures sought by the West. Top foreign ministry officials have also participated in the Geneva talks.

At the same time, however, Beijing does not want the terms in a long-term nuclear deal to be so demanding that diplomacy fails—and sanctions continue. China envisions a final resolution that will protect Iran’s peaceful use of nuclear technologies, but effectively prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons.

China’s near-term goal is to do more business with Iran without facing the threat of being penalized for violating U.S. trade sanctions. The sanctions against Iran, which were announced in late 2011 and took effect in June 2012, subject any bank, company or government that does business with Iran’s Central Bank to American penalties.

To qualify for the U.S. waiver from the sanctions, issued every six months, Beijing has been forced to cut back its annual crude oil imports from Iran since 2012. China calculated that its economic and political interests would suffer more by ignoring the U.S. restrictions, which was also the basic reason for China’s acquiescence to U.S. sanctions against Iran.

Trade with Iran is critically important because China is now the world’s largest net oil importer, which is calculated as liquid fuels consumption minus domestic production. China’s dependence on foreign crude is expected to rise to 61 percent by 2015 from 54 percent in 2010. Iran was China’s sixth-largest oil supplier in 2013, fourth-largest supplier in 2012 and the third-largest r for most of the previous decade. In 2013, China imported an average of 428,840 barrels of oil per day from Iran. The 2012 restrictions on Beijing’s oil purchases from Iran have in turn undermined China’s energy security. Economic sanctions have reduced the overall supply on the global oil market, generally driving up the international price.

Economic sanctions also constrain China’s other trade with and investment in Iran. U.S. sanctions have hindered implementation of earlier agreements. In 2012, China was forced to cancel mega projects such as the $4.7 billion development of Phase 11 of South Pars gas field, one of the world’s richest reserves, and a $2 billion hydropower project.

Economic sanctions also constrain China’s other trade with and investment in Iran. U.S. sanctions have hindered implementation of earlier agreements. In 2012, China was forced to cancel mega projects such as the $4.7 billion development of Phase 11 of South Pars gas field, one of the world’s richest reserves, and a $2 billion hydropower project.

Sanctions have also obstructed China’s payment for its crude oil purchases. China owed Iran at least $22 billion for missed payments by the third quarter of 2013, an issue at the top of the agenda when Iranian Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani visited Beijing in October.

Chinese companies that have been sanctioned by the U.S. for their trade with Iran include:

• Zhuhai Zhenrong, a state-owned company with a military background and the largest Chinese importer of Iranian crude oil

• the Bank of Kunlun, controlled by China’s largest oil company, China National Petroleum Corporation.

• and Poly Technologies, a subsidiary of state-owned defense company China Poly Group.

Most of China’s oil comes from the Middle East, mainly countries allied with the United States. Because of those longstanding alliances, Beijing wants its own reliable ally in the region, both to supply oil and to counterbalance American power. China views Iran as the natural choice.

A peaceful settlement of the nuclear dispute between Iran and the six other powers—the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia—would also improve prospects for regional security, including uninterrupted energy supplies from the Middle East. In recent years, Iranian threats to block the Strait of Hormuz and a possible U.S. or Israeli military attack on Iran have cast a dark shadow over regional stability as well as production and transportation of oil vital to China.

A peaceful settlement of the nuclear dispute between Iran and the six other powers—the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia—would also improve prospects for regional security, including uninterrupted energy supplies from the Middle East. In recent years, Iranian threats to block the Strait of Hormuz and a possible U.S. or Israeli military attack on Iran have cast a dark shadow over regional stability as well as production and transportation of oil vital to China.

Iran is both a policy asset and a liability for China in its relations with the United States. Iran gives Beijing leverage against Washington when Washington needs cooperation on sanctions, but Iran also turns into a liability when Tehran fails to meet Washington’s demands.

China sees the improvement of U.S.-Iran relations as essential to a deal with Iran. Many Chinese analysts contend Iran’s quest for nuclear technology is due to its sense of vulnerability in the region and from U.S. pressure. Beijing contends that the main solutions lie in improving U.S.-Iran relations and/or developing a new regional security framework. The Chinese are now working to facilitate a dialogue between Iran and the West and lobby Iran to “participate in the talks with flexibility and pragmatism,” according to Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi.

At the same time, however, China does not want Washington and Tehran to get so close that the Sino-Iranian strategic alignment against the United States is undermined. Chinese leaders believe that maintaining strong ties with Iran gives it some leverage over U.S. policy. Iran’s regional aspirations also differ from China’s. Beijing is keen on building friendly ties with both Israel and Saudi Arabia, Iran’s top Middle East rivals.

Failure to reach a peaceful international settlement over Iran’s nuclear ambitions would be bad news for China. An Iranian nuclear weapon could lead to a regional nuclear arms race, which would be China’s worst nightmare. But many Chinese analysts believe that Iran will not follow in the footsteps of North Korea—and will not go so far as developing an atomic bomb and testing it.

Yun Sun is a fellow in the East Asia program at the Stimson Center, a nonprofit and nonpartisan international security think tank.

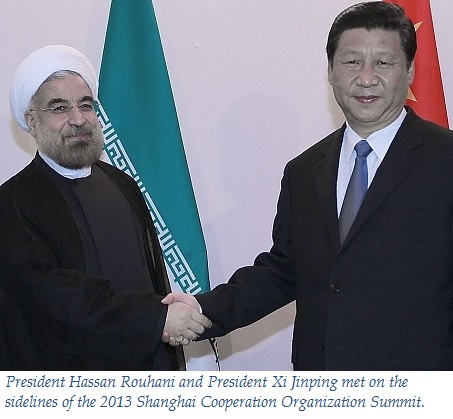

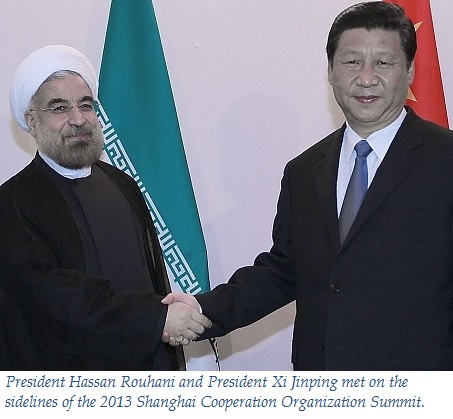

Photo credits: President.ir, Persian Gulf by Stevertigo at en.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org

China is the quiet giant in the latest diplomatic campaign to prevent Iran from getting a bomb. As Tehran’s largest trading partner, Beijing has enormous political and economic leverage over the Islamic Republic. As a veto-wielding member of the United Nations, its position can also make or break any resolution. China has often followed Russia’s lead on Iran policy, but its decisions reflect independent dynamics between Beijing and Tehran that will be key to its future actions.

China is the quiet giant in the latest diplomatic campaign to prevent Iran from getting a bomb. As Tehran’s largest trading partner, Beijing has enormous political and economic leverage over the Islamic Republic. As a veto-wielding member of the United Nations, its position can also make or break any resolution. China has often followed Russia’s lead on Iran policy, but its decisions reflect independent dynamics between Beijing and Tehran that will be key to its future actions. China now shares the concerns of the world’s major powers about Iran’s controversial nuclear program. Beijing wants to prevent Tehran from developing the world’s deadliest weapon, which would in turn dilute China’s nuclear power status. Beijing voted for four U.N. sanctions resolutions, although it balked at subsequent more punitive measures sought by the West. Top foreign ministry officials have also participated in the Geneva talks.

China now shares the concerns of the world’s major powers about Iran’s controversial nuclear program. Beijing wants to prevent Tehran from developing the world’s deadliest weapon, which would in turn dilute China’s nuclear power status. Beijing voted for four U.N. sanctions resolutions, although it balked at subsequent more punitive measures sought by the West. Top foreign ministry officials have also participated in the Geneva talks. Economic sanctions also constrain China’s other trade with and investment in Iran. U.S. sanctions have hindered implementation of earlier agreements. In 2012, China was forced to cancel mega projects such as the $4.7 billion development of Phase 11 of South Pars gas field, one of the world’s richest reserves, and a $2 billion hydropower project.

Economic sanctions also constrain China’s other trade with and investment in Iran. U.S. sanctions have hindered implementation of earlier agreements. In 2012, China was forced to cancel mega projects such as the $4.7 billion development of Phase 11 of South Pars gas field, one of the world’s richest reserves, and a $2 billion hydropower project. A peaceful settlement of the nuclear dispute between Iran and the six other powers—the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia—would also improve prospects for regional security, including uninterrupted energy supplies from the Middle East. In recent years, Iranian threats to block the Strait of Hormuz and a possible U.S. or Israeli military attack on Iran have cast a dark shadow over regional stability as well as production and transportation of oil vital to China.

A peaceful settlement of the nuclear dispute between Iran and the six other powers—the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia—would also improve prospects for regional security, including uninterrupted energy supplies from the Middle East. In recent years, Iranian threats to block the Strait of Hormuz and a possible U.S. or Israeli military attack on Iran have cast a dark shadow over regional stability as well as production and transportation of oil vital to China.