Between 2018 and 2023, Iran breached several of the most stringent restrictions imposed by the nuclear deal with the world’s six major powers. It enriched uranium to almost 84 percent—far higher than the 3.67 percent allowed by the deal or what would be needed for a civilian nuclear reactor to generate power and conduct medical research. Its enrichment was dangerously close to the 90 percent needed to fuel a bomb. It produced far more sophisticated centrifuges capable of enriching uranium faster. In a defiant standoff, Tehran also disconnected cameras installed by the International Atomic Energy Agency—the U.N. nuclear watchdog—to monitor its program and refused access to IAEA inspectors.

Iran’s advances were initially incremental and calibrated after President Donald Trump withdrew from the deal on May 8, 2018. The pace of Iran’s violations escalated after Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the father of Iran’s nuclear program, was assassinated in November 2020. In January 2021, Iran resumed enriching uranium to 20 percent at an underground nuclear facility, a major violation. In April 2021, Iran enriched uranium to 60 percent for the first time.

“Iran is taking actions to improve its capabilities to produce a nuclear weapon, should it make the decision to do so, while continuing to build its missile forces,” Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, warned in March 2023. Iran's breakout time – the time needed to enrich enough uranium to a level usable for one bomb – was down from a year when the deal was brokered in 2016 to “10 to 15 days” in 2023. Iran would also only need “several months to produce an actual nuclear weapon,” he said. The following is a timeline of Iran’s key nuclear advances and breaches since the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018.

Timeline

2019

July 1, 2019: Iran accelerated the rate of uranium production fourfold and surpassed the 300-kilogram (661-pound) limit on its stockpile of low-enriched uranium hexafluoride (UF6), the equivalent of 202.8 kilograms (447.1 pounds) of low-enriched uranium.

July 8, 2019: Iran increased enrichment from 3.67 percent—suitable for fueling nuclear power reactors—to 4.5 percent.

Related Material: The Impact: Iran Breaches Nuclear Deal

Sept. 25, 2019: Iran installed 20 IR-6 and 20 IR-4 advanced centrifuges at the Natanz nuclear facility near Isfahan. The IR-6 centrifuge could enrich uranium up to 10 times faster than the first-generation IR-1, according to Iranian officials. Centrifuges cascade together to produce fissile material. A report by the U.N. nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) also verified that Iran had installed a cascade of 164 IR-4 and 164 IR-2m centrifuges. The JCPOA had limited Iran to using just over 5,000 IR-1s.

Nov. 4, 2019: Iran began operating 30 new IR-6 centrifuges, doubling its number of the advanced machines. The chief of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, Ali Akbar Salehi, said that Iran was operating 60 of the centrifuges. Salehi added that Iran went from producing about 450 grams (1 pound) of low-enriched uranium a day to 5 kilograms (11 pounds). He said that Iran’s stockpile had grown beyond 500 kilograms (1,102 pounds).

Nov. 5, 2019: Iran began enriching uranium at the Fordo facility. The heavily fortified facility, built inside a mountain, was intended to be a research facility under the JCPOA, not an active enrichment site.

Nov. 5, 2019: Iran began enriching uranium at the Fordo facility. The heavily fortified facility, built inside a mountain, was intended to be a research facility under the JCPOA, not an active enrichment site.

Nov. 11, 2019: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had increased its stockpile of enriched uranium to 372.3 kilograms (or about 821 pounds), beyond the JCPOA limit. The watchdog also reported that inspectors had found traces of uranium “at a location in Iran not declared to the agency.”

Nov. 16, 2019: Iran informed the IAEA that its stock of heavy water exceeded the 130-metric ton limit under the JCPOA. On the following day, the watchdog confirmed that the Heavy Water Production Plant was active and that Iran had 131.5 metric tons of heavy water. Heavy water is often used as a moderator to slow down reactions in nuclear reactors.

2020

Jan. 5, 2020: Iran said that it would not abide by restrictions on uranium enrichment capacity, percentage of enrichment, stockpile size of enriched material, and research and development.

Jan. 25, 2020: Iran had accumulated 1,200 kilograms of low-enriched uranium, according to Ali Asghar Zarean, an aide to Iran’s nuclear chief.

June 5, 2020: The IAEA said that Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium had grown far above the amount permitted by the JCPOA. Iran possessed 1,571.6 kg of low enriched uranium, a 50-percent increase since February. Its stockpile of heavy water remained slightly above the 130-metric ton limit set by the JCPOA.

Sept. 4, 2020: The IAEA reported that Iran’s stockpile of low-enriched uranium reached 2,105 kilograms, or about 10 times more than the JCPOA limit. Iran also began operating slightly more advanced centrifuges, but not enough shorten its breakout time, which remained three to four months.

Nov. 11, 2020: The IAEA reported that Iran's stockpile of low-enriched uranium reached 2,443 kilograms, or about 12 times more than the JCPOA limit, indicating a slower rate of growth since the previous U.N. report. But Iran also began using more advanced centrifuges at Natanz to enrich uranium.

Nov. 17, 2020: The IAEA reported that Iran began feeding uranium gas into 174 IR-2M advanced centrifuges at Natanz.

Dec. 4, 2020: Iran informed the IAEA that it would install three new cascades of advanced centrifuges. Each cascade was made up of more than 150 centrifuges.

2021

Jan. 4, 2021: Iran resumed enriching uranium to 20 percent at Fordo, an underground nuclear facility, a major breach of the JCPOA. Enriching uranium up to 20 percent brought Iran to where it was before the nuclear accord.

Jan. 13, 2021: Iran’s ambassador to the IAEA, Kazem Gharibabadi, announced that Iran would produce uranium metal to help develop a new fuel for the Tehran civilian research reactor. But producing uranium metal was prohibited under the JCPOA because the material is necessary for making nuclear weapons. The metal can be used to cover the fuel rods that power a nuclear reaction. Iran said it would take four to five months to install the necessary equipment to produce uranium powder, which could then made into metal.

Feb 2, 2021: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had completed installation of 174 more IR-2M centrifuges at Natanz and began feeding uranium gas into them. In total, Iran was enriching uranium with 5,060 IR-1 centrifuges and 348 IR-2M centrifuges at Natanz.

Feb. 10, 2021: Iran had produced 3.6 grams of natural uranium metal, the IAEA confirmed. It was not permitted to manufacture uranium metal until 2031 under the deal. Iran also blocked "snap" inspections of undeclared nuclear sites. Iran would need 500 grams of highly enriched uranium metal for a nuclear weapon core.

Feb. 17, 2021: Iran informed the IAEA that it would install two new cascades of advanced centrifuges at Natanz. Each cascade had 174 IR-2M centrifuges and would enrich uranium up to 5 percent.

Feb. 23, 2021: Iran suspended compliance with the Additional Protocol, a voluntary agreement that grants inspectors “snap” inspections and was part of the 2015 nuclear deal.

Mar. 8, 2021: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had begun feeding uranium gas into a third cascade of advanced centrifuges at Natanz. A fourth cascade of IR-2M centrifuges was installed but not enriching uranium, while installation of a fifth cascade was ongoing. Each cascade had 174 IR-2M centrifuges.

March 15, 2021: Iran began enriching uranium at the Natanz facility with advanced IR-4 centrifuges. The IR-4 was the second type of advanced centrifuge, after the IR-2M, operating at the Natanz facility. The JCPOA had stipulated that Iran could only enrich at the facility with IR-1 centrifuges.

Apr. 1, 2021: The IAEA confirmed that Iran had begun enriching uranium with a fourth cascade of 174 IR-2M centrifuges. Iran was now using a total of 696 IR-2M centrifuges at Natanz.

April 10, 2021: Iran began testing advanced IR-9 centrifuges at Natanz. The IR-9 could enrich uranium 50 times faster than the IR-1.

April 16, 2021: Iran began enriching uranium up to 60 percent. Iran also planned to install 1,000 additional centrifuges at Natanz.

April 21, 2021: Iran installed more advanced centrifuges at the Natanz nuclear facility, the IAEA reported. Iran had a total of 1,044 IR-2M centrifuges and 348 IR-4 centrifuges installed at Natanz.

May 11, 2021: Iran had enriched uranium to 63 percent, the IAEA reported. The level of enrichment was "consistent with the fluctuations of the enrichment levels (described by Iran)," the agency told member states.

May 31, 2021: The IAEA estimated that Iran had 3,241 kilograms of enriched uranium, an increase of 273 kilograms since the last quarterly report. The estimate was the smallest increase in Iran's nuclear stockpile since August 2019.

June 15, 2021: Iran had produced 6.5 kilograms (14 pounds) of 60 percent enriched uranium, the government reported. The country also was on track to produce more uranium enriched to 20 percent than required by a law passed by Parliament in December. “The Atomic Energy Organization was supposed to produce 120 kg (265 lbs) of 20 percent enriched uranium in a year," spokesperson Ali Rabiei said. "According to the latest report, we now have produced 108 kg (238 pounds) of 20 percent uranium in the past five months."

June 23, 2021: Iran said that it would allow its monitoring deal with the IAEA to expire on June 24 before deciding whether to extend it. "After the expiration of the agreement's deadline, Iran's Supreme National Security Council (will) decide about the agreement's extension at its first meeting," presidential chief of staff Mahmoud Vaezi said.

July 6, 2021: Iran started the process to produce 20 percent enriched uranium metal, the IAEA reported. Iran had produced a small amount of uranium metal in February 2021, but it was not enriched.

Aug. 14, 2021: The IAEA reported that Iran had produced 200 grams (0.44 pounds) of uranium metal enriched up to 20 percent. The metal would be used to fuel the Tehran Research Reactor, Iran previously claimed. But the metal could also be used to produce the core of a nuclear weapon.

Aug. 17, 2021: Iran was using a second cascade of centrifuges to enrich uranium to nearly weapons-grade level, the IAEA reported. Tehran added a cascade of 153 advanced IR-4 centrifuges to enrich uranium up to 60 percent. Uranium needs to be enriched up to 90 percent to fuel a nuclear bomb.

In April, Iran had begun enriching uranium to 60 percent, the highest level of enrichment that it had publicly acknowledged. In May, the IAEA reported that Iran was using 164 IR-6 centrifuges to enrich uranium up to 60 percent.

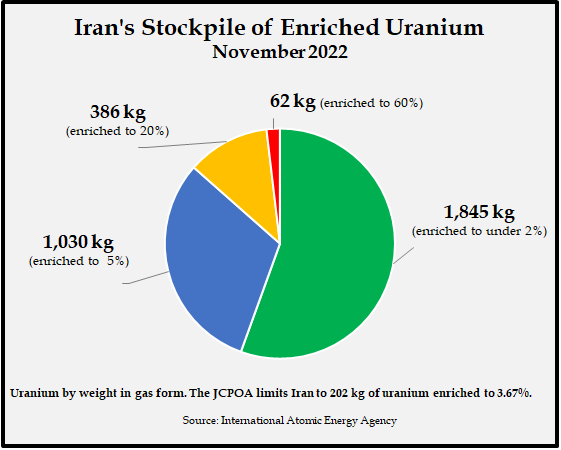

Sept. 7, 2021: The IAEA reported that Iran’s uranium enrichment capacity continued to increase, which experts subsequently warned could allow it to amass sufficient fuel for a single nuclear bomb within one to two months. Iran had stockpiled more than 2,400 kilograms of enriched uranium, a nearly 800-kilogram decrease because Tehran had enriched stockpiles of uranium enriched to under 2 percent to higher levels.

Sept. 23, 2021: The IAEA announced that inspectors had been denied entry to the centrifuge manufacturing plant at the Karaj facility near Tehran. The agency said the incident was a violation of the deal brokered on September 12. “The Director General reiterates that all of the agency’s activities referred to in the joint statement for all identified agency equipment and Iranian facilities and locations are indispensable in order to maintain continuity of knowledge,” the IAEA stated.

Oct. 23, 2021: The IAEA monitoring program in Iran was “no longer intact,” Grossi warned in an interview with NBC News. Iran has not allowed the watchdog to repair cameras that monitor centrifuge production at the Tesa Karaj facility outside Tehran. Iran had alleged that Israel sabotaged in an explosion at the Tesa Karaj facility in June. One camera was damaged, and another was destroyed.

Iran’s decision to limit IAEA access “hasn’t paralyzed what we are doing there, but damage has been done, with a potential of us not being able to reconstruct the picture, the jigsaw puzzle,” Grossi said. If and when the JCPOA is restored, the world’s six major powers will need to understand the status of Iran’s program, he added.

Nov. 17, 2021: In a report, the IAEA said that Iran had twice turned back inspectors at a facility that manufacturers parts for centrifuges used to enrich uranium. The facility in Karaj, outside Tehran, could be again manufacturing parts for advanced centrifuges. Since February 2021, IAEA had been unable to inspect the site because of a law passed in December 2020 curtailing access for inspectors. The IAEA also reported that 170 advanced IR-6 centrifuges had been installed at the underground facility at Fordo since September.

2022

Jan. 31, 2022: Iran had moved its centrifuge manufacturing workshop from Karaj to Isfahan, the IAEA reported.

May 30, 2022: Iran had stockpiled more than 18 times the amount of enriched uranium allowed under the 2015 nuclear deal, an unprecedented advance, according to a leaked report by the U.N. nuclear watchdog. The growing stockpile meant that Iran could amass sufficient fuel for a single nuclear bomb in a few weeks, although experts claimed that the so-called “breakout time” had decreased to a mere 10 days—or less. “This idea of crossing the line, it’s going to happen,” Director General Grossi, told reporters on June 6. “Having a significant quantity [of highly enriched uranium] does not mean having a bomb,” he said. “Iran can stop, through negotiations, or they themselves can decide to slow down.”

June 8, 2022: The IAEA’s Board of Governors, led by the United States, Britain, France, and Germany, passed a resolution criticizing Iran over unexplained traces of uranium. The resolution expressed “profound concern” that Iran had not provided credible or accurate information on uranium traces found at three locations not declared by the government “despite numerous interactions” with the IAEA. The resolution passed 30 to 2, with three abstentions. Russia and China, which have veto power at the U.N. Security Council, opposed the resolution. India, Pakistan and Libya abstained.

Iran “deplored” the resolution and retaliated by removing 27 cameras that monitor various aspects of its nuclear activities under provisions of the JCPOA. It also moved to install two cascades of advanced centrifuges IR-6 centrifuges in Natanz, which is Iran’s biggest facility for uranium enrichment.

July 25, 2022: Iran’s nuclear chief, Mohammad Eslami, said that IAEA monitoring cameras would remain off until the 2015 nuclear deal was restored. He also refused to respond to the agency’s questions about the uranium traces. "The claimed PMD (possible military dimensions) cases and locations were closed under the nuclear accord and if they (West) are sincere, they should know that closed items will not be reopened,” Eslami said.

Aug. 3, 2022: Iran had installed three cascades of advanced IR-6 centrifuges at the Natanz fuel enrichment plant, according to an IAEA report. Tehran had also told the agency that it planned to install six IR-2m cascades at the site.

Aug. 29, 2022: Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi stipulated that Iran would only agree to restore the 2015 nuclear deal if the IAEA closed the investigation into traces of uranium found at undeclared sites. “Without resolving safeguards issues, talking about an agreement would be meaningless,” Raisi said.

Sept. 7, 2022: The IAEA reported that Iran had accumulated enough uranium enriched to 60 percent that, if enriched further to 90 percent, could fuel one bomb. The JCPOA had capped Iran’s enrichment at 3.57 percent. The watchdog also said that it could not “provide assurance that Iran’s nuclear programme is exclusively peaceful” because Tehran failed to cooperate with an investigation into past activities at undeclared sites.

Oct. 10, 2022: Iran had installed one cascade of advanced IR-4 centrifuges and six of IR-2M centrifuges at the Natanz fuel enrichment plant, according to a leaked IAEA report. Tehran had also informed the agency of plans to install three cascades of advanced centrifuges at the same site.

Nov. 22, 2022: Iran announced that it had started enriching uranium to 60 percent purity at Fordo, the underground nuclear facility. It had already been enriching to 60 percent at Natanz. The move came a week after the IAEA Board of Governors passed a resolution calling on Iran to explain traces of uranium found at undeclared sites. “We had said that Iran will seriously react to any resolution and political pressure,” nuclear chief Mohammad Eslami said. Iranian media reported that advanced IR-6 centrifuges were being used.

Nov. 22, 2022: Iran announced that it had started enriching uranium to 60 percent purity at Fordo, the underground nuclear facility. It had already been enriching to 60 percent at Natanz. The move came a week after the IAEA Board of Governors passed a resolution calling on Iran to explain traces of uranium found at undeclared sites. “We had said that Iran will seriously react to any resolution and political pressure,” nuclear chief Mohammad Eslami said. Iranian media reported that advanced IR-6 centrifuges were being used.

2023

January 2023: The IAEA discovered that Iran had altered the connection between cascades of centrifuges – the cylindrical machines that enrich uranium – at the Fordo facility without notifying the U.N. watchdog. Inspectors also found traces of uranium enriched to 83.7 percent, very close to weapons-grade purity or 90 percent. Iran claimed that “unintended fluctuations in enrichment levels may have occurred,” according to a February IAEA report. The agency concluded that Iran had not accumulated uranium enriched to 83.7 percent.

Feb. 28, 2023: Iran had accumulated 87.5 kilograms (192.9 pounds) of uranium enriched to 60 percent, an increase of 40 percent since the previous quarterly IAEA report. Its total stockpile of enriched uranium was 3,760.8 kilograms (8,291.1 pounds).

March 8, 2023: After years of stonewalling, Iran pledged on March 4, 2023 to cooperate with a U.N. probe into traces of uranium at three undeclared sites that date back to a covert program before 2003. Tehran also promised to reinstall monitoring equipment, including cameras, that had been removed from nuclear facilities in June 2022. The IAEA and Iran “put a tourniquet on the bleeding of information and lack of continuity of knowledge,” Rafael Grossi, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), said after two days of talks in Tehran.

May 2023: The IAEA reportedly began reinstalling cameras at Iranian nuclear sites. Iran had removed 27 cameras in June 2022.