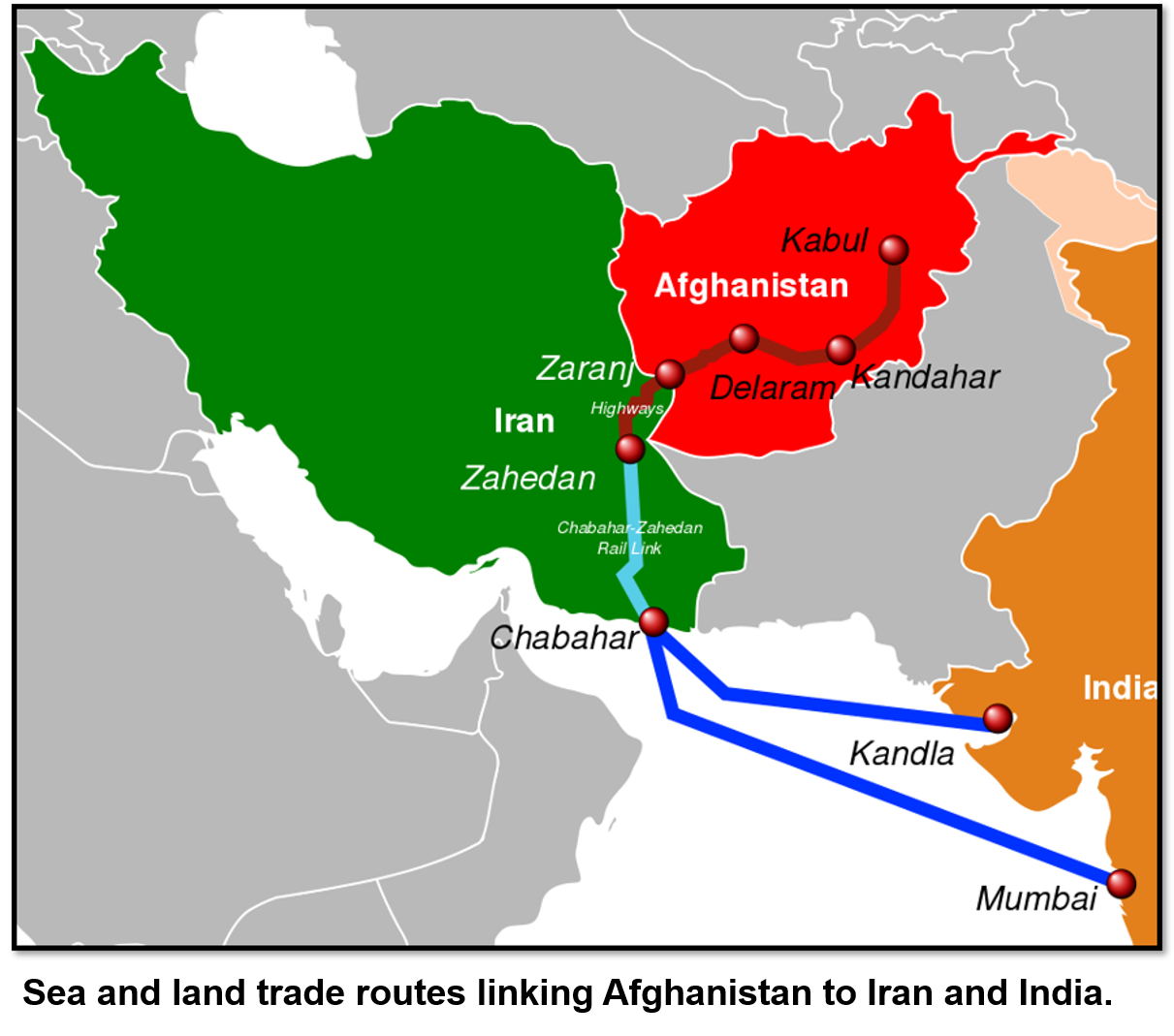

Many of Iran’s most pressing issues – in politics, the environment, the economy, health and security – converge in Sistan and Baluchistan. The largely mountainous southeast province is one of Iran’s most strategic frontiers. It shares a nearly 200-mile border with Afghanistan and a nearly 575-mile border with Pakistan. Chabahar, Iran’s only oceanic port, is on its coast on the Gulf of Oman. Chabahar has the potential to be a key trading hub for the Middle East and South Asia.

Sistan and Baluchistan, the second largest of Iran’s 31 provinces, is slightly larger than North Dakota or about the size of Syria. But it is sparsely populated with just 2.8 million people, just over 3 percent of Iran’s 84 million people. It is the only province in which more people – 51 percent – live in rural areas than in cities. Nationwide, 74 percent of Iran is urban. More than 600,000 people live in and around Zahedan, the provincial capital.

Sistan and Baluchistan, the second largest of Iran’s 31 provinces, is slightly larger than North Dakota or about the size of Syria. But it is sparsely populated with just 2.8 million people, just over 3 percent of Iran’s 84 million people. It is the only province in which more people – 51 percent – live in rural areas than in cities. Nationwide, 74 percent of Iran is urban. More than 600,000 people live in and around Zahedan, the provincial capital.

“Sistan,” a derivation of the Old Persian “Sakastana,” refers to the northern part of the province near the Afghan border and the ethnic Persians who reside there. Persians form a majority of Iran’s population, but they are a minority in Sistan and Baluchistan province.

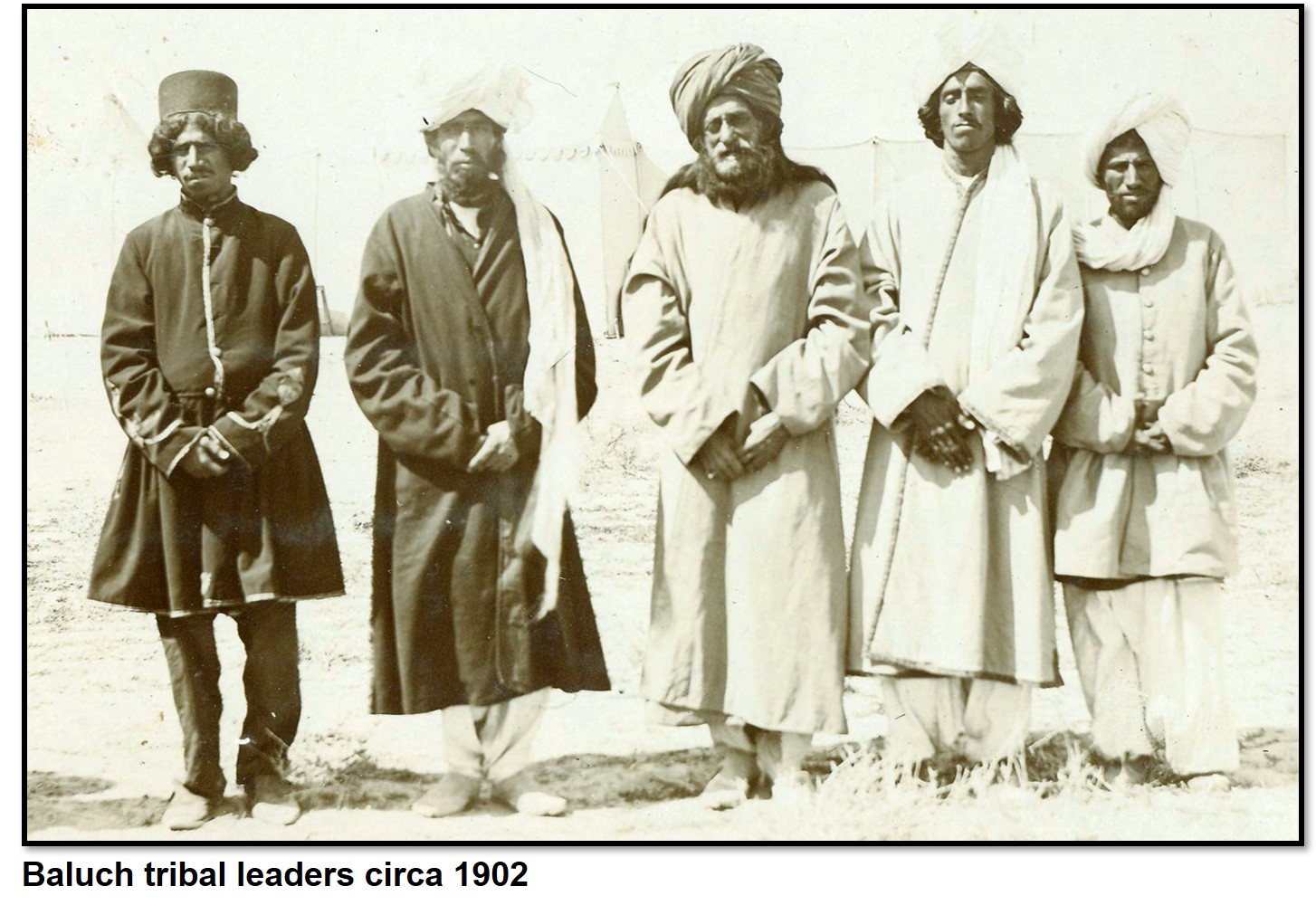

“Baluchistan” refers to the southern, western and eastern parts of the province, where the ethnic Baluch are concentrated. Iran is home to 1.5 million to 2 million Baluch, who make up about two percent of the national population but are the majority in Sistan and Baluchistan. The vast majority of the Baluch are Sunni, living in a predominantly Shiite country. Society is organized along tribal and clan lines. More than 6 million Baluch live in neighboring Pakistan and another 600,000 in Afghanistan.

In ancient times, the region connected civilizations and trade between South Asia and the Middle East. It was part of the ancient Persian Empire under Darius I, who ruled from 522 to 486 B.C.E. Alexander the Great marched his armies through the region to reach India in 326 B.C.E and lost many soldiers to the harsh conditions and rugged terrain on the return trip the following year.

Related Material: "Iran's Troubled Provinces - Khuzestan"

Ethnic, Sectarian and Political Tensions

The region that includes present-day Sistan and Baluchistan, which was historically part of Afghan, Arab, Greek, Indian, Mongol, Persian and Turkic empires, has changed hands many times over the millennia. The origins of the Baluch are unclear, but they were first mentioned in Persian and Arabic texts in the 8th and 9th centuries A.D. The Baluch have remained fiercely independent throughout history. Local dynasties attained varying degrees of autonomy or independence between the 11th and 17th centuries.

In the 19th century, the greater Baluchistan region, spanning Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, was divided by the British colonial power in south Asia between 1870 and 1872. British telegraph workers surveyed the area and defined Iran’s border with Afghanistan and British-ruled India (later Pakistan) to settle territorial disputes with the Qajar dynasty, which ruled Iran from 1789 to 1925.

In the 19th century, the greater Baluchistan region, spanning Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, was divided by the British colonial power in south Asia between 1870 and 1872. British telegraph workers surveyed the area and defined Iran’s border with Afghanistan and British-ruled India (later Pakistan) to settle territorial disputes with the Qajar dynasty, which ruled Iran from 1789 to 1925.

In 1897, Sardar Hossein Khan, a Baluch tribal chief, led an insurgency against the Qajar dynasty. The uprising ended three years later when the shah appointed Khan to be the local governor. The Baluch maintained a high degree of autonomy for three decades. In 1925, Reza Shah Pahlavi finally deposed the Qajars, already weakened by the 1906 Constitutional Revolution, and began to solidify his rule across the country. In 1928, he sent an army to wrest control from Baluch tribal chiefs. Several Baluch tribes launched two rebellions, which both failed, in 1931 and 1938. The Pahlavis redrew provincial boundaries to divide the Baluch among multiple provinces, such as Kerman and Hormozgan, and forcibly resettled Baluch elsewhere in Iran.

The Qajars, the Pahlavis and, since 1979, the Islamic Republic of Iran, have primarily viewed Sistan and Baluchistan as a security liability. Tehran has long worried that the Baluch could rally, perhaps with their brethren in Pakistan, to seek greater autonomy or even independence. After the 1979 revolution, Baluch separatists reportedly began to receive support from outside Iran. Tehran has accused the United States, Britain, Israel, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia of supporting Baluch separatists.

The central government has done little to integrate the Baluch into Iranian society. Poor socioeconomic conditions have exacerbated ethnic tensions. “Areas with large Baluchi populations were severely underdeveloped and had limited access to education, employment, health care, and housing,” according to the State Department’s 2019 report on human rights. In 2018, life expectancy in Sistan and Baluchistan was the lowest of any Iranian province. In the last census, the province also had a literacy rate of only 76 percent, compared to 93 percent in Tehran province.

The central government has repeatedly tried to suppress Baluch identity. The government has reportedly sent hundreds of Shiite missionaries to convert the predominantly Sunni Baluch. The government has closed, and, in some cases demolished Sunni mosques and religious seminaries. It has also used public education to promote an Iranian national identity, with Shiism as its foundation. Most elementary and high school teachers in Sunni Baluch areas are also reportedly Shiite. Persian is also the sole language of instruction, which disadvantages the Baluch.

Some separatist groups have cited discrimination and socioeconomic conditions as the key grievances for their opposition to Tehran. Since 2003, the militant Islamist group Jundallah, or “Soldiers of God,” has fought for Sunni rights. “The only thing we ask of the Iranian government is to be citizens. We want to have the same rights as the Iranian Shiite people. That's it. We do not want discrimination between Sunnis and Shiites in this country,” founder Abdolmalek Rigi said in an interview with Al-Arabiya in 2008.

Jundallah has attacked both civilian and government targets. Tehran describes the organization as a radical terrorist and separatist organization backed by its enemies. U.S. officials “secretly encouraged and advised” Jundallah starting in 2005, according to an ABC News report in 2007. But the United States, which designated Jundallah a terrorist organization in 2010, has denied providing support. The group has been less active since Jundallah splintered after Rigi was captured and executed by Iran in 2010. But the movement has spawned several other militant groups, including Jaish ul Adl (JUA), Ansar al Furqan, and Harakat Ansar Iran.

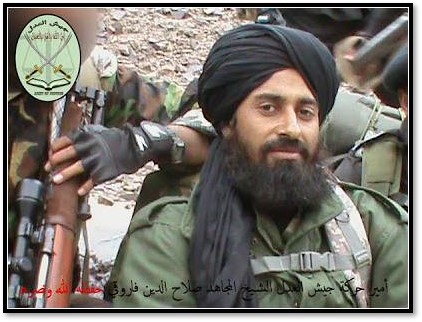

JUA (Army of Justice) was founded in 2012 and began attacking Iranian security forces the following year. It has been the most active Baluch insurgent group in Iran. It has launched suicide bombings, carried out assassinations, taken hostages and laid mines. JUA’s founder and leader is Salahuddin Farooqui (also known as Abdul Rahim Mulazadeh), who comes from the Baluchistan province in Pakistan; he has ties to communities on both sides of the border. JUA uses Pakistan as a base of operations.

JUA (Army of Justice) was founded in 2012 and began attacking Iranian security forces the following year. It has been the most active Baluch insurgent group in Iran. It has launched suicide bombings, carried out assassinations, taken hostages and laid mines. JUA’s founder and leader is Salahuddin Farooqui (also known as Abdul Rahim Mulazadeh), who comes from the Baluchistan province in Pakistan; he has ties to communities on both sides of the border. JUA uses Pakistan as a base of operations.

In 2015, Farooqui described the group as a “defensive military organization designed to safeguard the national and religious rights of the Baluch people and Sunnis in Iran.” JUA’s rhetoric reflects the influence of Salafism, an ultraconservative interpretation of Sunni Islam. The group pejoratively refers to Iranian military officials and state-controlled media have claimed that Saudi Arabia and the United States support the group. But the United States designated it a terrorist organization in July 2019. The size of the group is unknown, in part because it is composed of decentralized military cells. The Voice of America and Israel Defense website reported that the group had an estimated 500 members, but it was unclear how many were full-time fighters.

In 2015, Iran arrested Javid Dehghan, an ethnic Baluch, who was accused of being a JUA leader. The judiciary convicted Deghan for his alleged involvement in the killing of two Revolutionary Guards and leading a raid to abduct five border guards, one of whom was killed. But Amnesty International alleged that Dehghan’s confessions were extracted under torture and that his trial was “grossly unfair.” In January 2021, the U.N. human rights office urged Iranian authorities to review Dehghan’s case, but he was hanged on January 30.

🇮🇷#Iran: We strongly condemn the series of executions – at least 28 – since mid-December, including of people from minority groups. We urge the authorities to halt the imminent execution of Javid Dehghan, to review his and other death penalty cases in line with human rights law.

— UN Human Rights (@UNHumanRights) January 29, 2021

Economic Issues

Sistan and Baluchistan is one of the most underdeveloped provinces in Iran. As of 2016, nearly half of the population “lived under the poverty line and could not afford the minimum 2,100 calories necessary for subsistence,” according to an IranWire analysis of census data. “Villages don't have adequate drinking water or even bread. By any standards they are living in deplorable conditions,” Ali Yar Mohammadi, a member of parliament from Zahedan, said in 2018. Some parents have been forced into marrying their daughters off as early as age nine, in part due to the financial incentive of dowries. Iran’s civil code requires parental permission and court authorization for marriages of girls under age 13 and boys under age 15, but not all marriages are registered.

The lack of industrial, agricultural and transportation infrastructure has limited the number of employment opportunities. The drought could force more than half a million people to migrate to other provinces, warned Mohammad Naeim Aminifard, a member of parliament from the northern city of Zabol. “People in Sistan and Baluchistan have lost everything and have nowhere to go. Most people in the province are farmers, but the drought has destroyed their livelihood,” he said in 2018.

Unemployment in some areas ranged between 40 to 60 percent, Yar Mohammadi said in May 2020. Unemployment was between 20 and 25 percent in Zahedan, the provincial capital. As of 2018, more than half of its residents faced a shortage in running water, so residents had to rely on truck deliveries to help close the gap.

The central government, however, has taken limited steps to improve conditions across the province. “Despite sanctions and economic problems, the government has paid special attention to Sistan and Baluchistan, and this province has the highest budget growth among the provinces of the country,” Governor Ahmad Ali Mohabati said in May 2020. In recent years, the government has renovated schools, connected highways to railways, expanded the gas supply, connected railways and rehabilitated farm land. In May 2020, President Hassan Rouhani inaugurated three major water projects and 807 agricultural projects, worth a combined total of more than $170 million. The government has also reduced taxes on businesses in deprived areas or allocated tax exemptions for up to 20 years in special economic zones.

The province has also expanded exports – including cement, fruits, vegetables and other goods – to neighboring countries, mainly to Afghanistan and Pakistan. From March 2019 through March 2020, Sistan and Baluchistan exported more than $1.09 billion in goods, up 17 percent from the previous year.

The province has potential for further economic growth in tourism, the fish industry and fruit farming. The province already has some 370 active mines, but millions of tons of mineral reserves, including gold, have yet to be extracted.

The development of the Chabahar port was intended to be a game changer for the province and the wider region. In 2016, Iran, India and Afghanistan signed an agreement to develop the port into a shipping hub with rail links to India via Afghanistan that would circumvent Pakistan. But development of Iran’s only port with access to the India Ocean failed to progress, largely due to concerns over U.S. sanctions reimposed in 2018 after President Donald Trump withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal.

The development of the Chabahar port was intended to be a game changer for the province and the wider region. In 2016, Iran, India and Afghanistan signed an agreement to develop the port into a shipping hub with rail links to India via Afghanistan that would circumvent Pakistan. But development of Iran’s only port with access to the India Ocean failed to progress, largely due to concerns over U.S. sanctions reimposed in 2018 after President Donald Trump withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal.

Related Material: “The Broken Promise of Chabahar”

As of mid-2020, the port had been spared from sanctions because of U.S. interests in Afghanistan’s economic growth. But India also had not found a partner company to run operations at Chabahar, and Western firms were reluctant to sell equipment. Even if the project was on schedule, the Iranian rail link from Zahedan to Chabahar was not due to be completed until March 2022.

Border Issues and Drug Smuggling

The province’s remote location along the Afghan and Pakistani borders has made it a haven for smuggling. Iran has built trenches and fences to prevent trafficking, but the local residents on both sides of the border still manage to pass goods back and forth. Some have used catapults to foist smaller parcels over the border. Some Baluch have trafficked gasoline, undocumented Afghans workers, and drugs. Smugglers have also trafficked undocumented Afghan workers.

Smugglers have transported fuel over the Pakistani border for resale in neighboring countries. They have taken advantage of Iran’s fuel prices, some of the lowest worldwide. On February 22, 2021, Iranian border guards reportedly shot and killed at least two smugglers along the border. Fuel smugglers then attacked a police station in Saravan, on the Iranian side of the border. Border guards shot and wounded several people. On the following day, dozens of protesters stormed a district governor’s office and set fire to a police car.

Baluch militant groups have used profits from drug smuggling to support their operations. Iran is a major hub for opiates produced in Afghanistan smuggled to Europe and beyond. As of 2018, Iran accounted for 91 percent of the world’s opium seizures, 48 percent of morphine seizures and 26 percent of heroin seizures, according to the U.N. World Drug Report 2020. Iran has reportedly executed at least 10,000 people for drug crimes since 1988. It has also lost some 4,000 police officers and border guards in the fight against smugglers, who are often well-armed.

The transit of drugs into Iran has exacerbated domestic use. As of 2018, some three percent of the population, close to three million people, were addicted to drugs, according to the interior minister. The most widely used illicit drugs are opiates, cannabis products and methamphetamines. “If you walk through the streets at night and in the areas next to the cemeteries, you easily see people, including women, young boys and girls, sleeping in cardboard boxes, side by side a swarm of addicts,” Aziz Sarani, a representative of Sistan and Baluchistan in the Supreme Council of Provinces, recounted in 2018. Drug use in the province has been complicated by the lack of public health programs.

Drug use has in turn contributed to the spread of HIV. In 2013, the government reported that 68 percent of 71,000 Iranians living with HIV had contracted the virus through use of contaminated needles or syringes.

Environmental Problems

Sistan and Baluchistan’s environmental problems are a product of climate change, government mismanagement and tensions with neighboring Afghanistan.

By 2015, the province’s annual precipitation had decreased by 50 percent over the previous 40 years, according to the National Drought Warning and Monitoring Center. In rural areas, drinking water has been scarce. As of 2017, nearly 1,700 villages in the province had no running water and relied on tanker deliveries. Some residents were dependent on gathering scant rain water in pits and then boiling it.

The province also suffers from dust storms produced by two decades of drought and high temperatures, as high as 110 degrees in the summer. The season for dust storms has expanded from 120 days a year to 180 days. In 2018, a sandstorm sent nearly 250 people to the hospital with breathing, heart and eye problems. In 2016, the city of Zabol had the world’s dirtiest air, according to the World Health Organization.

A province long dependent on agriculture—nurtured by both irrigation and natural rain—has been hard hit by the drought. The central government has discouraged water-intensive crops, such as rice. Since 2017, many farmers have been unable to plant and harvest any crop, making them increasingly dependent on government aid.

Iran has also blamed the province’s problems on Kabul’s decision to increasingly dam the Helmand River, which flows into Iran. Starting in the 1950s, Afghanistan built two dams on the Helmand river, the Kajaki and the Grishk. The Helmand River in Iran has run increasingly dry for the past two decades. Parts of the river have run dry for up to 10 months out of the year. “We cannot remain indifferent to what is damaging our environment,” President Rouhani said in 2017. “The construction of several dams in Afghanistan – the Kajaki, Kamal Khan and Selma dams and other dams in the north and south of Afghanistan – impacts our Khorasan and Sistan and Baluchistan provinces.” By 2020, irrigated farming in Sistan and Baluchistan had become almost impossible, according to Habibollah Dahmardeh, a member of parliament from Zabol.

Afghan officials counter that Iran has received more than its fair share of water under a 1973 treaty. In July 2020, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani visited Nimroz province to check on the construction of a third dam on the Helmand river, the Kamal Khan. Nimroz, Afghanistan’s only Baluch-majority province, borders Sistan and Baluchistan. The new dam will generate electricity and irrigate land for Afghanistan, but it will further restrict water flow to Iran. “Our running water is our pride, and in a few years, Afghans will re-own billions of cubic meters of water that we had lost ownership of,” Ghani said. The dam is due to be completed in late 2020.

The dams have further imperiled the Hamoun wetlands, which span Iran and Afghanistan. For thousands of years, the wetlands, which include three lakes, have provided local communities with water. In 2000, the Hamoun wetlands were the world’s seventh largest wetland. But they have been drying up due to drought as well as overuse and inefficient use of water. They used to cover up 2,185 square miles, about two-thirds on the Iranian side. But by 2004, its surface water was largely gone.

The dry soil has contributed to the cycle of dust storms. Occasional rainfall or floods temporarily revitalize parts of the wetlands but not enough to reverse the decades of damage. The wetlands still constitute Iran’s third-largest lake.

Restoring the wetlands would require several billion cubic meters of water to be redirected to Hamoun, a former government official estimated. In April 2020, the European Union and the U.N. Development Program pledged $11.7 million to help rehabilitate the vulnerable ecosystem.

Dry soil also leaves Sistan and Baluchistan vulnerable to flash floods. In January 2020, three days of heavy rain – the equivalent of a year’s worth – displaced thousands, killed at least three and destroyed crops, homes and infrastructure. The floods did at least $53 million in damage, with limited government relief to compensate.

Related Material: "Iran's Troubled Provinces - Khuzestan"

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of The Iran Primer at the U.S. Institute of Peace. Follow him @GarrettNada.