Mehdi Khalaji

- For several decades, Iran’s Shiite clerical establishment has proven extremely effective at mobilizing the Iranian masses.

- The Shiite clergy were historically independent from government. But especially under Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Iranian government seized control of the “sacred” and co-opted the clerical establishment.

- Since 1979, Iran’s theocratic regime has deprived the entire clerical class of its autonomy—but also made it rich and powerful.

- Any serious crisis in Iran could jeopardize the clergy’s favored position in government. To retain its legitimacy and religious standing, the clergy may have to distance itself from politics.

Overview

Shiite clerics have been able to mobilize the Iranian masses far better than any other socio-political authority. Clerics form the broadest social network in Iran, exerting their influence from the most remote village to the biggest cities. So while most opposition groups participated in the 1979 revolution, the clergy established hegemony over Iran’s new political system after the shah’s ouster. They emerged from a crowded field for several reasons. First, Islamic revolutionaries ruthlessly eliminated their rivals. Second, the regime tapped into the popularity and legitimacy conferred by its call to Islam, a force rooted in Iran’s social history. None of the other revolutionary political factions benefited from the traditional legitimacy and social network provided by the Shiite clerical establishment.

The new Islamic government tapped into the clergy’s power to achieve its agenda—not only on religious or political matters. After the Iran-Iraq War, clerics were dispatched throughout the country to encourage families to have fewer children. A soaring birth rate after the revolution had almost doubled the population within a decade from 34 million to 62 million, which threatened to stifle future economic growth. The government’s ploy was effective; the Iranian birth rate declined dramatically.

The new Islamic government tapped into the clergy’s power to achieve its agenda—not only on religious or political matters. After the Iran-Iraq War, clerics were dispatched throughout the country to encourage families to have fewer children. A soaring birth rate after the revolution had almost doubled the population within a decade from 34 million to 62 million, which threatened to stifle future economic growth. The government’s ploy was effective; the Iranian birth rate declined dramatically.The regime and the clerical establishment now have a symbiotic relationship that shapes both politics and production of the next clerical generation. The alliance no longer tolerates clerics who think or behave outside the framework of the regime’s specific Islamic ideology. Prominent clerics such as late Ahmad Ghabel, Mohsen Kadivar, Hassan Youssefi Eshkevari and Mohammad Mojtahid Shabestari have been excommunicated for heretical interpretations of Islamic theology.

But relations between the clergy and the government have also had adverse effects on the clerics’ social authority. In the 1997 presidential election, the clerical establishment supported the conservative speaker of parliament, while the majority of people voted for the dark-horse reformist candidate Mohammad Khatami. In the 2005 election, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won in part because of voters’ frustration with government clerics, who were increasingly associated with corruption and elitism. He was the first non-cleric to win the presidency since Khomeini had a falling out with early technocrats shortly after the revolution. But Ahmadinejad lost his clerical power base due to failed economic policies, corruption and mismanagement that exacerbated pressure from tightened international sanctions on Iran. In 2013, Iranian voters again elected a cleric, Hassan Rouhani, against six lay candidates.

The political guardian

Support from Shiite clerics was traditionally one of the monarchy’s sources of political legitimacy. But the 1906-1911 Constitutional Revolution ended clerical control over Iran’s educational and judicial systems. Reza Shah Pahlavi’s forced secularization and modernization campaigns in the early twentieth century further marginalized Iran’s religious leaders. His son, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, initiated land reform that alienated both of the monarchy’s traditional power bases: the clerics and large landowners.

Feeling abandoned by the state, major landowners formed an alliance with clerics incensed at the gradual decay of their own social and political power. The shah attempted to protect himself from waves of Islamic revolutionary sentiment by using minor clerics, such as Ayatollah Ahmad Khansari and Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari. But they lacked sufficient clout to prop up the monarchy.

After the revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini announced the formation of the Islamic Republic of Iran and declared that ultimate political authority would rest in the hands of a senior cleric, the velayat-e faqih, or guardianship of the jurist. The idea represented a revolution within Shiism, which had for centuries deliberately stayed out of politics and never before ruled a state. A clerical front soon emerged to oppose the specific idea of a velayat-e faqih and the broader concept of reinterpreting Shiite theology. Many clerics believed the velayat-e faqih’s absolute authority was actually non-Islamic.

The successor

Khomeini died in 1989, and the Assembly of Experts selected Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as the new supreme leader. Khamenei was not a natural successor of Khomeini. He lacked serious religious and political credentials and was noticeably devoid of charisma. Many other figures in his generation were closer to and seen as potential heirs to Khomeini’s rule.

Khamenei’ chief rival was Ayatollah Ali Montazeri, who had actually been appointed Khomeini’s successor years earlier. But Montazeri had been fired after sharp disagreements, particularly after the execution of thousands of political prisoners in 1988. Khamenei’s appointment disappointed the traditional Shiite clergy; he was able to assume control only with the help of Iran’s security apparatus and state propaganda.

Clerical purge

Khamenei gradually began to consolidate his hold on power. He was aided by the deaths of grand ayatollahs, such as Mohammad Reza Gopayegani and Shahab Al-Din Marashi Najafi, who had fought to guarantee the clergy’s independence from government. But the regime also launched a second concerted attack on the clerical establishment. It began with an attempt to monopolize management of the clergy, many of whom ran their own seminaries, had their own followings, and earned their own incomes.

The regime computerized and unified data on the clergy of all ranks to make information on their economic and intellectual lives accessible to the government. It also co-opted the clerical establishment through hefty government stipends as well as other exclusive and profitable privileges. Khamenei increasingly became the ultimate authority over all religious seminaries, as well as supreme leader of the Iranian government. By throwing in with the regime, the clergy also increasingly abdicated their role as the exclusive “managers of the sacred affaires” of Iranian society. The clerical establishment effectively became the central ideological apparatus of the state. And the government increasingly gained control of defining the “sacred.”

The regime computerized and unified data on the clergy of all ranks to make information on their economic and intellectual lives accessible to the government. It also co-opted the clerical establishment through hefty government stipends as well as other exclusive and profitable privileges. Khamenei increasingly became the ultimate authority over all religious seminaries, as well as supreme leader of the Iranian government. By throwing in with the regime, the clergy also increasingly abdicated their role as the exclusive “managers of the sacred affaires” of Iranian society. The clerical establishment effectively became the central ideological apparatus of the state. And the government increasingly gained control of defining the “sacred.”The Islamic regime now uses its control over mosque and state to suppress both “popular Islam,” Sufism and religious intellectualism, which have all gained ground among the public since the mid-1990s. “Popular Islam” is the faith as lived and practiced by ordinary people, and does not necessarily correspond with theological Islam or official Islam imposed by state. Sufism is an interpretation of Islam which focuses on spiritual content of the Prophet Mohammad’s message, rather than Islamic law. And religious intellectualism centers on liberal democratic interpretations of Islam. All three extend the borders of the “sacred” far beyond what is acceptable to the Islamic Republic. All three threaten the regime’s version of “official Islam.”

The regime’s expanding power over traditionally independent clerics has stifled religious thought and even forced clerics to disconnect from the establishment. Many do not have the intellectual freedom even outside the seminaries; they are still harassed by intelligence services. Another clerical minority has tried to withdraw from politics and avoid public activities, instead devoting themselves to worship and education. But the majority of clerics prefer the benefits of government financial resources and the political advantages of a close association with the regime.

Important organizations

- Supreme Council of Qom Seminary: A group of clerics who are in charge of policy planning in Iran’s seminaries. Members of the council are appointed by the supreme leader and can be dismissed by him. The executive director of the clerical establishment is appointed by this council.

- Center for Management of Seminaries: The executive management body of the clerical establishment which oversees all educational, administrative and economic activities of the clerics.

- Association of Teachers of Qom Seminary: A group of conservative clerics which oversees the Supreme Council of the Qom Seminary under supervision of the supreme leader. This group does not include all important teachers or scholars of the seminaries.

- Association of Teachers and Scholars of Qom Seminaries: A group consisting of former officials of the Islamic Republic, as well as a few middle-ranking reformist clerics. This reformist group is marginal and has little support from the grand ayatollahs.

- Association of Militant Clerics of Tehran: A group of clerics who participated in the revolution. It includes current and former members of the government. Along with the Bazaar – the traditional market – this group forms a pillar of old conservative establishment in Iran.

- Al-Mustafa International University: A university owned and run by Ayatollah Khamenei. It specializes in educating non-Iranian clerics and has branches in several other countries.

- Special Court of Clerics: A court which works outside the judiciary system and does not respect the country’s juridical codes. The court’s head is appointed and dismissed by the supreme leader. The court is one of the government’s main tools for controlling clerics.

- Imam Sadeq 83 Brigade: A military unit whose members are clerics. This unit was created during the Iran-Iraq War but now serves as the police force of the clerical establishment and works under supervision of Ayatollah Khamenei.

Prominent clerics

- Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani: A grand ayatollah in Najaf, Iraq. Sistani enjoys the most widespread following in the Shiite world. But his followers outside Iraq mostly look to him for answers on private religious matters rather than political issues.

- Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Current leader of Islamic Republic and the de facto head of the Shiite clerical establishment. Khamenei’s authority over the Shiite religious network extends beyond Iran, and is the richest and most effective Shiite religious network in the world.

- Ayatollah Naser Makarem Shirazi: A pro-regime ayatollah who has thousands of followers inside Iran. He is best known for his extra–clerical economic activities and benefits from government which have made him one of Iran’s richest clerics in Iran.

- Mohammad Mojtahid Shabestari: A cleric who reads Islamic texts by modern hermeneutics and the methodology of historical criticism. He believes that Sharia or Islamic law is not valid in anything related to the public sphere. He unconditionally defends the universal declaration of human rights. Since the early 2000s, he chose to forsake his robe and turban in order to disassociate himself with the pro-regime establishment.

- Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi: Originally Iranian but born and trained in Iraq, he was the leader, then the spokesman of the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq. After the death of Ayatollah Khomeini, in 1989, he approached the new supreme leader and refashioned his political identity and agenda. Shahroudi had a major role in helping Ayatollah Khamenei with issuing fatwas. He was appointed by Khamenei as a member of the Guardian Council and then the judiciary chief for 10 years. As of 2015, he portrayed himself as a marja’ (source of emulation) and ran a religious office in Najaf, Iraq as well as Iran. Shahroudi, who benefits from government advantages in his international business, is considered to be among the wealthiest clerics.

Trendlines

- Compared to the pre-revolutionary era, the quality of seminary education in Iran has declined significantly. Government intervention in all aspects of clerical life, including seminary curriculum, has changed the clergy’s traditional way of thinking and living.

- The clerical establishment is now producing mostly missionaries and preachers, rather than true scholars of Islamic law and theology. The symbiotic relationship between the clergy and the country’s judicial and political order will continue the qualitative decay of Islamic education. Ironically, as Islamic scholarship decays, so too will the clergy’s ability to provide convincing religious justification for the government’s actions.

- Since 1989, more non-clerical power centers have emerged or have gained power. Power centers, such as Revolutionary Guards, have different and sometimes incompatible political and economic interests, which make them the clergy’s rival rather than ally.

- Although the clerics in the Assembly of Experts will carry out the legal process of selecting the next supreme leader, they are unlikely to have much of a say in the decision. Due to the supreme leader’s role as commander and chief of the armed forces, the Revolutionary Guards have a vested interest in the appointment of Khamenei’s successor and may therefore play a bolder role in the process. Political shareholders in the intelligence, judicial and business communities may also try to ensure a result that benefits them.

- Iranian reformists such as the pro-democracy, student and women’s movements have secular demands: they call for elimination of various forms of discrimination embodied in the constitution. This vision for Iran leaves little room for clerics’ leadership. Even if a minority of clerics would like to join civil society movements, it would be as followers rather than leaders.

Mehdi Khalaji, a senior fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, studied Shiite theology in the Qom seminary of Iran.

This chapter was originally published in 2010, and is updated as of October 2015.

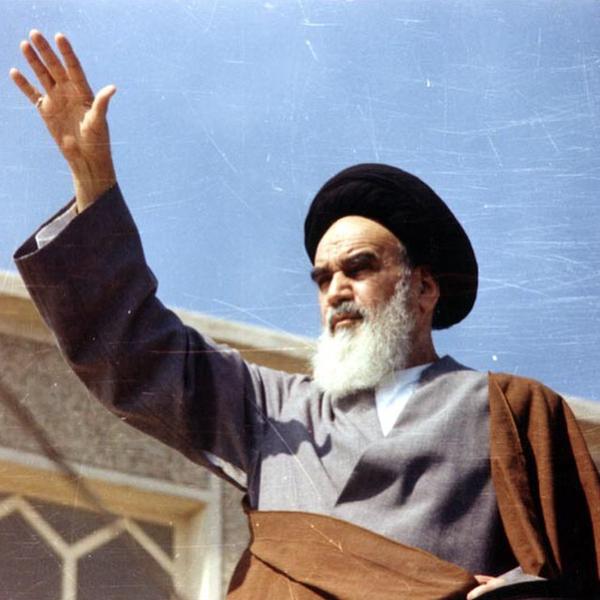

Photo credits: Khomeini via @IRKhomeini (Twitter account); Masoumeh Shrine (Haram 3) by Mohammad mahdi P9432 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/license/by-sa/4.0)], via WIkimedia Commons; Khamenei via Khamenei.ir and Facebook.

Politics_Khalaji_Clergy 2015.pdf200.17 KB