On April 6, the European Union convened indirect talks between Iran and the United States in Vienna. The goal was to create two separate roadmaps to bring Iran and the United States back into compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Tehran would need two to three months to reverse its breaches of the nuclear deal, Ali Akbar Salehi, the head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, said on April 2. But Iran could immediately stop some activities, such as enriching uranium to 20 percent. Under the deal, Iran was only allowed to enrich to 3.67 percent.

The new diplomacy is designed to reverse the policy of President Donald Trump, who abandoned the accord in May 2018. He also reimposed punitive economic sanctions that had been lifted by the deal. After the Trump decision, Iran continued to comply with its obligations for more than a year. But in July 2019, it began breaching the agreement. Iran’s breaches were incremental and calibrated until the assassination of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, a top nuclear scientist, in November 2020.

Iran then took steps—including enriching uranium up to 20 percent—that could bring Tehran closer to sufficient fuel for a bomb. Enriching from 20 percent to weapons-grade levels—90 percent or higher—could be a relatively quick process if Tehran made the political decision to actually produce the world’s deadliest weapon. As a result of Iran’s breaches, the so-called breakout time – or the time Iran would need to enrich enough uranium to make one nuclear bomb – has shortened from one year in 2015 to about three months in 2021, the Institute for Science and International Security estimated. The following is a rundown of Iran’s breaches of the JCPOA that would need to be reversed.

July 1, 2019

Under the nuclear deal, Tehran was allowed to stockpile only 300 kilograms of low-enriched uranium. It was expected to sell or exchange any surplus. But on May 3, 2019, the United States vowed to sanction any country or company that helped Iran sell or exchange surplus, which left it with few alternatives to remain in compliance with the JCPOA. In retaliation, Tehran announced it would no longer honor the limit on its stockpile. On July 1, it accelerated the rate of production fourfold.

“We had previously announced this and we have said transparently what we are going to do,” Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said on July 1. “We consider it our right reserved in the nuclear deal.” Iran also vowed to increase its uranium enrichment closer to weapons-grade levels if Europe failed to provide economic relief promised in the JCPOA.

The breach did not pose an immediate proliferation threat, according to the Arms Control Association’s Kelsey Davenport. Iran would need to produce at least 1,050 kilograms of highly-enriched uranium —nearly four times its stockpile at the time—to develop a nuclear weapon. If Iran produced enough fissile material for a bomb, it would still need to convert the gas into powder and then fabricate it into a metallic form to create the fissile core of a nuclear warhead. The uranium would then have to be fitted with explosives and integrated into a delivery system, such as a ballistic missile. The strict monitoring mechanisms set up in the JCPOA would also provide early warnings if Tehran decided to build a bomb.

Iran could quickly reverse the step by diluting the excess enriched uranium, which would return it to a natural level—and which is not restricted in the JCPOA. Tehran could undo the break in days or weeks.

July 8, 2019

On July 8, Iran increased enrichment from 3.67 percent--a level suitable for fueling nuclear power reactors--to 4.5 percent.

Today, Iran is taking its second round of remedial steps under Para 36 of the JCPOA. We reserve the right to continue to exercise legal remedies within JCPOA to protect our interests in the face of US #EconomicTerrorism. All such steps are reversible only through E3 compliance.

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) July 7, 2019

The slight breach, by itself, did not pose a short-term proliferation risk. Enrichment was still well below weapons-grade, which is more than 90 percent enriched uranium. It was also significantly lower than the 20 percent enrichment that Iran had reached in 2010, before the JCPOA in 2015. It would also still take Iran at least a year to amass enough weapons-grade fuel for a weapon; before the deal, the so-called “breakout time” was about two to three months.

Click here for more information on the first and second breaches.

September 25, 2019

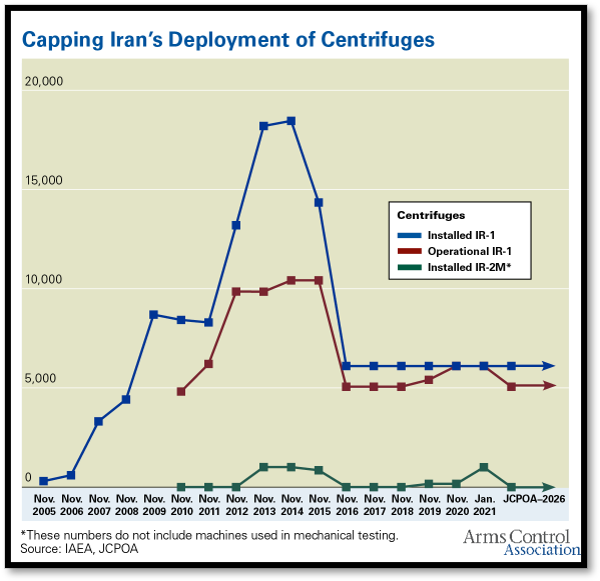

On September 25, Iran again breached the JCPOA by installing advanced centrifuges—20 IR-6s and 20 Ir-4s—to enrich uranium at the Natanz facility near Isfahan. The IR-6 centrifuge can enrich uranium 10 times faster than the first-generation IR-1, according to Iranian officials. The JCPOA had limited Iran to using just over 5,000 IR-1s. Centrifuges cascade together to produce fissile material. A report by the IAEA also verified that Iran had installed a cascade of 164 IR-4 and 164 IR-2m centrifuges.

Iran’s third breach of the agreement was more significant than the previous two. It accelerated the production of fissile material and decreased the breakout time needed to develop a nuclear weapon. With advanced centrifuges, Tehran could start stockpiling enriched material for an eventual bomb. “Under current circumstances, the Islamic Republic of Iran is capable of increasing its enriched uranium stockpile as well as its enrichment levels and that is not just limited to 20 percent,” Behrouz Kamalvandi, the spokesperson the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, said. “We are capable inside the country to increase the enrichment much more.”

On November 4, Iran began operating 30 new IR-6 centrifuges, doubling its number of the advanced machines. The chief of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, Ali Akbar Salehi, said Iran was operating 60 of the centrifuges, which are some 10 times more efficient than the IR-1s allowed under the JCPOA. The announcement coincided with the 40th anniversary of the takeover of the U.S. embassy in Tehran by students.

Salehi said that Iran went from producing about 450 grams (1 pound) of low-enriched uranium a day to 5 kilograms (11 pounds). He said Iran’s stockpile had grown beyond 500 kilograms (1,102 pounds). The JCPOA had limited Iran’s stockpile to 300 kilograms (661 pounds).

November 7, 2019

On November 5, President Rouhani announced that Iran would start injecting gas into 1,044 centrifuges at Fordo in one day. The heavily fortified facility, built inside a mountain, was intended to be a research facility under the JCPOA, not an active site. The IR-1 centrifuges at Fordo had been spinning but were not enriching uranium. Salehi, Iran’s nuclear chief, specified that that the centrifuges would enrich uranium up to five percent at Fordo.

Iran’s 4th step in reducing its commitments under the JCPOA by injecting gas to 1044 centrifuges begins today. Thanks to US policy and its allies, Fordow will soon be back to full operation. https://t.co/Mpkk9d0BIp

— Hassan Rouhani (@HassanRouhani) November 6, 2019

Rouhani emphasized that Iran could reverse course on its nuclear program if Europe finds a way to shield Iran from U.S. sanctions. “We should be able to sell our oil,” Rouhani said. “We should be able to bring our money” into the country.

On November 6, Kamalvandi clarified that uranium gas would only be injected into 696 of the centrifuges and that the remaining 348 would produce stable medical isotopes. Iran injected uranium gas into the centrifuges early on November 7.

In a report dated November 11, the IAEA confirmed that Iran increased its stockpile of enriched uranium to 372.3 kilograms (or about 821 pounds), beyond the 202.8 kilogram (about 447 pounds) limit under the JCPOA. It also reported that its inspectors had found traces of uranium “at a location in Iran not declared to the agency.”

November 7, 2019

On November 16, Iran informed the IAEA that its stock of heavy water exceeded the 130 metric ton limit under the JCPOA. On the following day, the watchdog confirmed that the Heavy Water Production Plant was active and that Iran had 131.5 metric tons of heavy water. Heavy water is often used as a moderator to slow down reactions in nuclear reactors.

Heavy water reactors can produce plutonium for use in nuclear weapons. But heavy water poses less of a proliferation concern than uranium because spent fuel from heavy water reactors must be reprocessed to separate the plutonium.

Iran briefly exceeded the heavy water cap in 2016, but the parties to the JCPOA allowed Iran to store its excess until it found another country to buy part of its supply.

January 5, 2020

On January 5, Iran announced its fifth step away from its commitments to the JCPOA. Tehran said it would not abide by restrictions on uranium enrichment capacity, percentage of enrichment, stockpile size of enriched material, and research and development. But Foreign Minister Zarif implied that Iran would continue allow the IAEA to monitor its nuclear program. He also left the door open to returning to full compliance if sanctions are lifted.

As 5th & final REMEDIAL step under paragraph 36 of JCPOA, there will no longer be any restriction on number of centrifuges

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) January 5, 2020

This step is within JCPOA & all 5 steps are reversible upon EFFECTIVE implementation of reciprocal obligations

Iran's full cooperation w/IAEA will continue

The Arms Control Association’s Kelsey Davenport and Julia Masterson outlined potential scenarios for Iran's breakout time:

The ambiguity of the announcement gives Iran considerable latitude to calibrate its actions. Iran could choose to remain on its current trajectory by slowly installing additional IR-1 machines and enriching uranium to less than five percent. Similar to Iran’s earlier steps, this will slowly and transparently erode the 12 month breakout time, or the time to produce enough nuclear material for one bomb, established by the JCPOA. The action would also be reversible, in line with Iran’s earlier violations, to keep open the option of returning to compliance with the accord.

Alternatively, if Iran wants to increase pressure more quickly, it could quickly install and begin operating its more advanced IR-2s and remaining IR-1s. There is also the possibility of further violating the provisions of the JCPOA that Tehran breached in 2019. Iran exceeded the limit on uranium enrichment to 3.67 percent uranium-235 in July by slightly increasing levels to 4.5 percent. Resuming enrichment to 20 percent uranium-235, for example, could significantly shorten the breakout time. Iran enriched to the 20 percent level before negotiations on the JCPOA and officials have threatened to return to it.

On January 25, Ali Asghar Zarean, an aide to Iran’s nuclear chief, said the country had accumulated 1,200 kilograms of low-enriched uranium, far more than the 202.8-kilogram limit under the JCPOA. The announcement suggested Tehran had significantly ramped up enrichment since November, when the IAEA said the stockpile was 372.3 kilograms.

September 4, 2020

The IAEA reported that Iran’s stockpile of low-enriched uranium reached 2,105 kilograms, or about 10 times more than the JCPOA limit. The stockpile had grown some 544 kilograms since the last quarterly report, released in June. Iran also began operating slightly more advanced centrifuges, but not enough shorten its breakout time, which remained three to four months. When Iran was in full compliance with the JCPOA, its breakout time had been 12 months.

“While Iran’s persistent violations of the deal are troublesome, its rate of enriched uranium production has not increased over the course of 2020, indicating that Tehran is not actively dashing toward a bomb nor accelerating its production of fuel,” according to Kelsey Davenport and Julia Masterson, experts at the Arms Control Association. “This carefully calibrated approach supports assertions by Iranian leaders that its breaches of the JCPOA are a response to the U.S. reimposition of sanctions in violation of the accord and that Tehran will return to compliance with the nuclear deal if its conditions on sanctions relief are met.”

The IAEA report also noted that Iran continued to cooperate with continuous monitoring of its facilities, adhered the limit 5060 IR-1 centrifuge limit for Natanz, did not advance Arak heavy water research reactor construction and kept its heavy water stockpile just below 130 metric ton limit set by the JCPOA.

November 11, 2020

The IAEA reported that Iran's stockpile of low-enriched uranium reached 2,443 kilograms, or about 12 times more than the JCPOA limit. The stockpile had grown some 337.5 kilograms since the last quarterly report -- which indicated a slower rate of growth. But Iran also began using more advanced centrifuges at Natanz to enrich uranium. Europe expressed concern about the "irreversible consequences" of Iran's research and development of advanced centrifuges." Iran has engaged, for a year and a half now, in numerous, serious violations of its nuclear commitments," the European parties to the JCPOA said at an IAEA board meeting on November 18. "We continue to be extremely concerned by Iran’s actions, which are hollowing out the core non-proliferation benefits of the deal. Iran's breakout time was approximately three months, the Institute for Science and International Security estimated.

January 4, 2021

Iran resumed enriching uranium to 20 percent at an underground nuclear facility, a major breach of the 2015 nuclear deal. The landmark agreement, negotiated between Iran and six major world powers, stipulated that Tehran could only enrich uranium to 3.67 percent. It also banned uranium enrichment at Fordo – a facility built deep inside a mountain to protect it from a military strike – until 2031.

Enriching uranium up to 20 percent brought Iran to where it was before the nuclear accord: on the cusp of acquiring sufficient fuel for a nuclear weapon. Uranium must be enriched to 90 percent or above to fuel a weapon, but enriching uranium gets easier the more highly concentrated it is. Enriching from 20 percent to 90 percent could be a relatively quick process, if Tehran made the political decision to do so. Enriching to 20 percent could shorten its breakout time even further.

We resumed 20% enrichment, as legislated by our Parliament.

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) January 4, 2021

IAEA has been duly notified.

Our remedial action conforms fully with Para 36 of JCPOA, after years of non-compliance by several other JCPOA participants.

Our measures are fully reversible upon FULL compliance by ALL.

January 13, 2021

Iran’s ambassador to the IAEA, Kazem Gharib Abadi, announced that Iran would produce uranium metal to help develop a new fuel for the Tehran civilian research reactor. But producing uranium metal was prohibited under the JCPOA because the material is necessary for making nuclear weapons. The metal can be used to cover the fuel rods that power a nuclear reaction. Iran said it would four to five months to install the necessary equipment to produce uranium powder, which could then made into metal. On January 14, the IAEA confirmed that Iran had reported that it had started installing the necessary equipment.

February 10, 2021

The IAEA confirmed that Iran had enriched 3.6 grams of natural uranium metal. Under the deal, Iran was prohibited from manufacturing uranium or plutonium metals until 2030. Iran would need 500 grams of highly enriched uranium metal for a nuclear weapon core. The European parties to the deal had previously warned that there was "no credible civilian use" for the metals and that its production had "potentially grave military applications."

February 23, 2021

Iran suspended compliance with the Additional Protocol, a voluntary agreement that grants inspectors “snap” inspections and was part of the 2015 nuclear deal negotiated with the world’s six major powers. But Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that the step, and all other breaches of the deal, was "reversible" if the Biden administration lifted sanctions.

March 15, 2021

The IAEA confirmed that Iran had begun enriching uranium at Natanz with IR-4 centrifuges. The IR-4 was the second type of advanced centrifuge, after the IR-2M, operating at the Natanz facility. The JCPOA had stipulated that Iran could only enrich at the facility with IR-1 centrifuges.

April 10, 2021

Iran began testing its most advanced nuclear centrifuge, the IR-9, at the Natanz enrichment site. Under the nuclear deal, Iran could only operate 5,060 first-generation IR-1 centrifuges until 2025. The IR-9 can enrich uranium 50 times faster than the IR-1.

April 13, 2021

Iran said that it will begin enriching uranium to 60 percent, the highest level of enrichment that it has publicly acknowledged. The move would be a major breach of the 2015 nuclear deal and brought Tehran closer to having weapons grade uranium. The breach coincided with the planned resumption of indirect talks between the United States and Iran in Vienna over returning to the JCPOA.