What are the main power blocs shaping decisions in Iran?

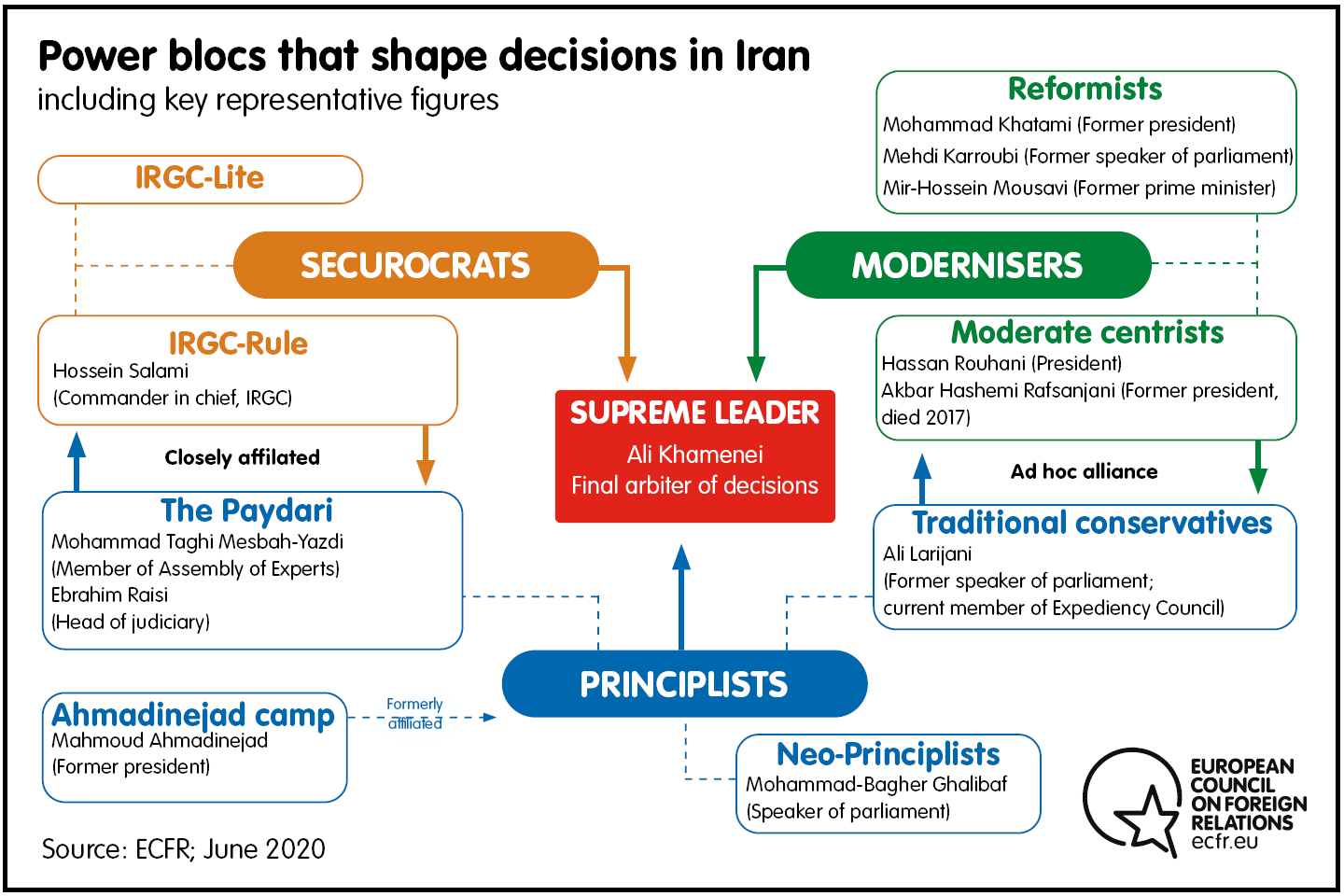

While the supreme leader is the ultimate decision-maker in Iran, three main groups operate within the nezam [system] framework: the ‘modernisers’; a political faction formally calling itself the ‘Principlists’; and ‘securocrats’. These three blocs all seek to gain the supreme leader’s support for their proposals, and thereby greater power. None of these groups is anti-establishment and they all accept the supreme leader’s role as the final arbiter. This is in contrast with, for example, those who recently participated in nationwide protests, some of them calling for radical changes such as the rejection of the entire political establishment.

The modernisers seek change within the parameters of the Islamic Republic. Relative to other camps, they take a conciliatory approach to domestic and foreign policy while generally supporting diplomacy with the West. This group includes ‘moderate centrists’ who currently control the executive branch under Hassan Rouhani’s presidency. Their primary goal is to make economic and technological progress by integrating Iran with the global economy. Key figures among moderate centrists have included pragmatic political operators such as Rouhani and former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who died in 2017.

Also belonging to the modernisers is a political group formally called the ‘Reformists’. Their main goal is to advance civil, social, and political rights within Iran. This group is led by former president Mohammad Khatami and is closely associated with the 2009 Green Movement protests, whose leaders remain under house arrest. The Reformists are currently sidelined, with some of their political organisations outlawed or severely weakened. Khatami himself is still an important political voice, and has galvanised support for Rouhani’s presidential campaigns.

However, members of the Reformists are increasingly distancing themselves from the moderate centrists, stating that they regret having tied “the fate of reform movement to Rouhani”. Reformists did poorly in the February 2020 parliamentary election. Their representatives had either been disqualified from standing in the first place, or their candidates failed to attract enough votes from an electorate disappointed by the pace of political and social progress these candidates had pushed for while serving in parliament. One Reformist figure predicts the faction “may well go through a metamorphosis” in the coming years: this camp needs to come up with a new strategy to both regain their popularity among voters, and to preserve their influence within the nezam.

Other Parts of the Report:

Who are the Principlists?

The second major camp comprises the Principlists, a political entity claiming to defend the core foundations of the 1979 revolution – including the fight against imperialism and corruption, as well as the protection of the poor. Figures associated with this group are known for populist messaging and policies that focus on social welfare. As for negotiations with the West, most Principlists maintain that such talks are harmful to Iran and that Europeans are not trustworthy. They are largely absolute devotees of the supreme leader. In return for their loyalty, Khamenei has increased their share of power over the years through appointments to important positions, such as those in the Guardian Council and the judiciary. That said, the Principlist camp includes such a wide range of subgroups that one political analyst describes the faction as a “herd of cats” – which, until the recent parliamentary election, found it difficult to coalesce in a way that would attract voters as the modernisers had in a string of votes since 2013.[3]

‘Traditional conservatives’ form part of the diverse Principlist camp. Key figures in this subgroup include members of the traditional clerical establishment and the recently retired speaker of parliament Ali Larijani, whom the supreme leader appointed in May to act as his adviser and serve as a member of the Expediency Council. Under Larijani’s leadership, traditional conservatives have been willing to join forces with moderate centrists on issues such as support for the JCPOA [Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action]. On the economic front, they also backed moderate centrists in implementing the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) road map, which entailed a series of financial sector reforms that European governments insist are necessary for Iran to reconnect with international banks. Other Principlists opposed, and successfully blocked, Iran’s full implementation of the FATF road map.

Who are the most powerful Principlists?

The alliance of traditional conservatives and the moderate centrist Rouhani administration is partly due to the increasing radicalisation of some Principlists (such as the ‘Paydari’ group described below), and the poor track record of former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. He brought with him a new corrupt political and economic network, while his administration’s diplomatic failure helped place Iran under extensive UN Security Council sanctions. In his first term in office, Ahmadinejad was affiliated with the Principlists. But, by his second term, he had fallen out of favour with the supreme leader and is no longer formally supported by the Principlists. There is now a recognised following of the ‘Ahmadinejad camp’ that is highly centralised around him personally and his populist social agenda. There are signs that Ahmadinejad will either look to stand in next year’s presidential election or field a candidate close to his camp.

The most powerful subgroup within the Principlists is known as the Paydari (the Front of Islamic Revolution Stability). Members of this subgroup have an ultraconservative and securitised approach towards governance, and they fiercely opposed the nuclear talks with the West. They generally prefer hard military power projection over conciliation with Iran’s enemies and are highly sceptical of diplomatic engagement with Europe. Hardline cleric Mohammad Taghi Mesbah-Yazdi oversees this strict school of thought, and is currently a member of the Assembly of Experts. Prominent figures endorsed by the Paydari camp in past elections include the head of Iran’s judiciary, Ebrahim Raisi, who lost the 2017 election to Rouhani, and Saeed Jalili, who led the nuclear talks under Ahmadinejad and currently represents the supreme leader at the SNCS. The Paydari camp now has a strong presence in parliament and will look to seize the presidency in 2021.

Finally, the ‘Neo-Principlists’ are a relatively new faction established by former mayor of Tehran and former IRGC senior general Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf after he lost the 2017 presidential election. Ghalibaf argues that the Principlists need an overhaul of the ageing top echelons, who dominate power in this camp. He wants the Principlists to be more inclusive of younger generations. This year Ghalibaf was elected to parliament and has been appointed speaker. However, voices within the Paydari group have been quick to criticise Ghalibaf for supporting the nuclear deal, and media outlets linked to the Principlists have described him as “inclined towards the liberalistic ideology of the other side [the Rouhani camp]”. Indeed, Ghalibaf has openly outlined his support for the nuclear talks, but has attacked but Rouhani for the details agreed under the JCPOA. Ghalibaf is increasingly viewed as an opportunist who not only carries weight with parts of the IRGC, but is willing to align with different political camps to increase his chances of standing in and winning next year’s presidential election.

Who are the securocrats?

The third camp that holds extensive power in Iran is the securocrats, whose core goals include increasing the IRGC’s control over Iran’s security, economic, and regional affairs. The securocrats have remained strong allies of Khamenei, helping him to contain internal upheaval and external threats. The IRGC is constitutionally mandated to defend Iran’s territorial integrity and the Islamic revolution. Using its influence on security matters, the IRGC has pushed the country to expand its military capabilities through homegrown technology and regional affiliates that deter and attack foreign enemies.

Unlike the modernisers and Principlists, who have formed a distinct political platform and whose leaders stand in elections, the IRGC generally keeps a low profile in the public political sphere. Currently, the Paydari group within the Principlists has close associations with the more hardline elements of the IRGC. As one expert has put it, the securocrats “don’t need a General Sisi [Egypt’s president] as they have enough figures with IRGC serving in the background without uniforms that can safeguard their stake in political battlefield”. Throughout the country, the IRGC has influence over local issues thanks to its broadly based, dedicated Basij units. The IRGC is also engaged with the SNSC and is directly answerable to the supreme leader as commander-in-chief. Given their close partnership with the supreme leader, the securocrats have access to a financial network overseen by Khamenei in addition to their own businesses, both of which help fund the IRGC’s activities.

One analyst studying IRGC networks concluded that, among the securocrats, the “dominant voices prefer IRGC-rule – while the minority prefer IRGC-lite order”, finding that some in the minority group support the modernisers on specific economic issues and the need to avoid war with the US. The dominant trend is led by “those at [the] forefront of fighting in Syria, who view everything, including internal politics, through that lens: politics is a battlefield of the war with US.” However, another senior expert in Iran viewed this matter differently, arguing that the Quds Force, which has been at the forefront of conflicts in the region, “has been obliged to be more pragmatic as they have to work and cut deals with different actors, tribes, and warlords in the region – Sunnis, Shia, and the Kurds”. While there are differences among the securocrats over how to exercise their immense power, the IRGC umbrella organisation headed by Brigadier General Hossein Salami and the IRGC’s Intelligence Organisation drive the hardline elements within the securocrats grouping. They have been emboldened by the US maximum pressure campaign to push Iran towards a more confrontational and securitised form of politics.

How have Iranian politics shifted since the United States withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions?

Several factors have caused the modernisers’ influence over these strategic portfolios to weaken in recent years. Firstly, as external US pressure has increased, the supreme leader has sought to homogenise the inner circle of leadership in order to reduce internal infighting in times of crisis and to be better able to deal with the US. The extensive disqualification of candidates affiliated with the modernisers and traditional conservatives prior to the 2020 parliamentary election suggests that Iran’s political system is tightening into a small group of acceptable elites known as the khodis – the insiders. Modernisers are currently attempting to resist this trend, however. For example, marking the Persian new year in March, foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif explicitly proposed an effort to break down barriers between the acceptable inner circle and those considered to be outsiders by the political elite, as well as for “mental housekeeping” to create unity in fighting covid-19 and US sanctions.

Secondly, the securocrats and the Paydari among the Principlists are the most fervent supporters of the supreme leader. As such, they have risen to power at the expense of elected institutions. As one expert explains, the IRGC was empowered during the war with Iraq because Khomeini “didn’t trust the American-trained armed entities that survived the revolution – and wanted a parallel back-up army devoted to the cause of the Islamic revolution.” This devotion to the role of the supreme leader has endured since the revolution, while successive elected presidents have experienced major tensions with Khamenei.

Today, the securocrats and the supreme leader are engaged in a partnership in which the IRGC and its nationwide network have created the Islamic Republic’s principal bedrock of support in terms of both voter base and individuals who have joined the IRGC and its Basij networks. As one senior figure deeply engaged with Iranian politics put it, the securocrats and the Principlists carry at least 30 percent of the country who are willing to “sacrifice extensively to preserve” the ruling order. And, as seen in the response to the November protests – which, according to Amnesty International, resulted in at least 304 deaths – this includes the extensive use of force against internal dissent.

Such devotion to, and protection of, the Islamic Republic appears to have become more important to the supreme leader as the US has sought to weaken Iran’s political system and economy. This is reflected in the supreme leader’s unequivocal support for the IRGC. In January, the IRGC's seemingly accidental downing of a Ukrainian airliner – which left 176 people dead – occurred hours after Iran retaliated against the US assassination of Soleimani by attacking American troops based in Iraq. This caused immense harm to the IRGC’s reputation, not least through what appeared to be an initial attempt to cover up its role. The event exposed rifts between the securocrats and the modernisers, with one senior adviser to Rouhani warning of the grave risks associated with military rule. At that moment, Khamenei could have moved to strike a new balance between the elected and unelected branches of the system. But, in a major speech following the crisis, Khamenei gave the IRGC his full support, hailing them as defenders of the Iranian nation.

Thirdly, the securocrats and hardline Principlists increasingly present themselves to the supreme leader and the wider public as stepping in to fill gaps left by the central government. This includes deterring military strikes on Iranian territory by the US or Israel; thwarting plots by the Islamic State group (ISIS) after a major attack in 2017; launching a military satellite into orbit; and providing disaster relief – most recently in response to covid-19. After several weeks in which Iran’s death rate from the pandemic made it one of the worst-affected countries in the region, the IRGC activated its Basij and financial networks across the country to help the poor, providing food, healthcare, and sanitation. These widely broadcast operations were also an attempt by the IRGC to restore their reputation and bridge the divide with Iran’s middle class following the airliner downing.

Why have the modernisers been weakened?

Finally, the difficulties the Rouhani administration has faced in recent years in improving the economy have weakened the modernisers more generally. The JCPOA’s economic benefits did not accrue to the Iranian people in the way that had been promised. The state of the economy is the key source of public discontent: as Rouhani nears the end of his term, the country is in a worse economic state than he found it in – despite the grand diplomacy he has undertaken with the West. Some of the president’s political allies are either distancing themselves from him or the JCPOA. One such figure is Ali Shamkhani, who is the secretary of the SNSC. He initially supported the JCPOA, but later argued that “Iran should have never inked the deal”.

For the public and the ruling elite, the JCPOA was a litmus test for whether the modernisers’ pro-diplomacy framework could gradually normalise Iran’s global position. As Iran is again facing international isolation due to US pressure, public opinion has moved against diplomacy and the political pendulum swung in favour of the Principlists during this year’s parliamentary election – in which they took 211 out of 290 seats. The modernisers secured just 19 seats (a sharp fall from 121 in the 2016 election). As one senior Iranian official described it, “the faction that delivers gets the votes”.

As a consequence of the four factors outlined above, the Principlists and the securocrats now control the judiciary, the legislature, the Guardian Council, powerful financial institutions, the state media networks, and most of the security apparatus. A quiet debate is emerging among the modernisers about whether to leave the presidential role uncontested in the 2021 election in order to reduce infighting within the nezam. As one person from the moderniser camp commented, if a figure from within the Principlist camp, who has the backing of the IRGC, became president, they “might get the job done with solving our problems with the US – and, if not, they can carry the political cost with voters”. Others interviewed for this paper warn that Ahmadinejad’s term in office provides a disastrous blueprint for what the securocrats and the Principlists would do, and that the modernisers should try to protect the country from worst-case scenarios by retaining the presidency.

What do we know about the succession of the supreme leader?

One factor that could significantly alter Iran’s future political trajectory is the succession of the supreme leader, who is 81 years old. There are many unknowns associated with the succession, including whether the role will be taken up by an individual or by a new council. Officials from the Assembly of Experts, a hardline-leaning body charged with appointing the supreme leader, have occasionally commented on the process, revealing that a three-member investigative committee deliberates with Khamenei on a confidential shortlist of candidates. Others note that this list is under review with an updated record of performance for the candidates. Khamenei is likely playing the leading role in the succession and will seek to ensure it is carried out in line with his preferences and in an organised manner. However, it seems improbable that a moderniser will succeed him.

What are the prospects for the modernisers?

Despite these shifts, the modernisers have not been entirely squeezed out. Although they have been badly burned by the aftermath of the JCPOA, the supreme leader has allowed Rouhani some space. As one senior figure deeply engaged in Iranian politics notes, “in many instances [the supreme leader] has restrained opposition forces from derailing the Rouhani administration”, such as by shielding nuclear negotiators from political attacks from the Principlists who seek to impeach them and by standing with the government’s decision to preserve the JCPOA after the US withdrawal from the deal. For now, the Rouhani administration’s entourage remains in the ‘insider’ group of the nezam. But, if the economy continues to tank on their watch, the modernisers will likely lose influence over strategic decisions and may be removed from high-ranking posts. In these circumstances, their pro-diplomacy vision for Iran stands even less chance of winning support than it does now.

This is an excerpt from a report first published by the European Council on Foreign Relations. Click here for the full text.

Ellie Geranmayeh is a senior policy fellow and deputy head of the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations.