Iranian opposition groups reflect diverse political grievances, ethnic tensions, and ideological trends. The regime’s most visible opponents are partially or entirely based outside Iran. Their goals are either regime change or self-determination for an ethnic group inside Iran. The government has banned, persecuted or prosecuted members of each of the five groups profiled here. Some groups have ties to neighboring governments in the region; others operate from Europe.

Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Ahwaz (ASMLA)

Overview

The Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Ahwaz (ASMLA) is a militant separatist group that seeks an independent state in Iran’s southwest Khuzestan province. Founded in 1999, the ASMLA began military operations in Khuzestan after violent unrest in April 2005. Since 2007, the movement’s political wings have operated in exile. The ASMLA split in 2015. It broke into two rival factions with headquarters in exile in Denmark and the Netherlands; each faction claims authority over the Mohiuddin Nasser Martyrs Brigade, a militia that operates underground inside Iran. The Martyrs Brigade has attacked oil and gas installations, security forces and banks in Khuzestan since 2005. In 2019, a native Ahwazi analyst told the Jamestown Foundation that the Martyrs Brigade had an estimated 300 members operating inside Iran.

The ASMLA has tapped into dissent among Iran’s Arab population, which accounts for between 2 percent and 4 percent of the country’s 84 million people. Most of Iran’s oil fields are in Khuzestan, but the local population has long complained that it does not reap benefits from oil revenues. Approximately 70 percent of Iran’s Arabs are Shiite Muslims. Since 2014, however, growing numbers of Khuzestan Arabs (also known as Ahwazi Arabs) have converted to Sunni Islam. The ASMLA has ties to Sunni organizations in Iran and abroad. It supports Sunni militant groups that oppose Iranian intervention in the Middle East. It dedicated a 2013 attack to the Syrian opposition, which is dominated by Sunnis.

Leadership

Ahwazi activists established the ASMLA in Khuzestan province. Habib Jaber Kaabi and Ahmad Mola Nissi were the group’s most visible founders. The ASMLA kept a low profile between 1999 and 2005. Kaabi later told Orient News that the group spent its first six years preparing “economically, politically and militarily.” In April 2005, the ASMLA played a major role in a four-day uprising that led to dozens of deaths by security forces, according to human rights groups. Kaabi and Nissi fled Iran after the protests and found political asylum in Copenhagen and The Hague, respectively.

In 2007, the ASMLA launched political and media operations from exile. Kaabi was the movement’s president in Denmark; Nissi led its political bureau from the Netherlands. In 2010, the ASMLA joined the National Organization for the Liberation of Ahwaz (also known as Hazm), an umbrella movement of some half dozen Ahwazi separatist groups based in Iran and abroad. In 2012, ASMLA representatives met with the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood to discuss an alliance against Iranian forces. Since 2012, ASMLA media have supported the Ahwazi liberation movement as well as Kurdish, Baluch, and Azeri opposition groups in Iran.

In May 2014, the ASMLA suspended its membership in the National Organization for the Liberation of Ahwaz. In October 2015, the faction in The Hague led by Nissi accused Kaabi of abusing his powers and dismissed him from the presidency; it appointed Nissi to replace Kaabi. The National Organization and three other Ahwazi groups that had been aligned with Kaabi defected to Nissi’s faction.

Since the 2015 schism, both factions have used the ASMLA name and flag. The media from the rival factions have both claimed attacks carried out in Khuzestan by the Martyrs Brigade since 2015. In 2018, the Kaabi faction in Denmark said it was a political arm of the Ahwaz National Resistance (ANR), an umbrella organization that oversees Ahwazi separatist groups in Khuzestan and in exile. The ANR’s structure, location and membership, however, are unclear.

In November 2017, Nissi was assassinated outside his home in The Hague. After a fourteen-month investigation, Dutch officials accused the Islamic Republic of hiring criminal middlemen to carry out the attack. Tehran denied its involvement in the murder. But the charges sparked ASMLA protests that turned violent outside the Iranian embassy in The Hague.

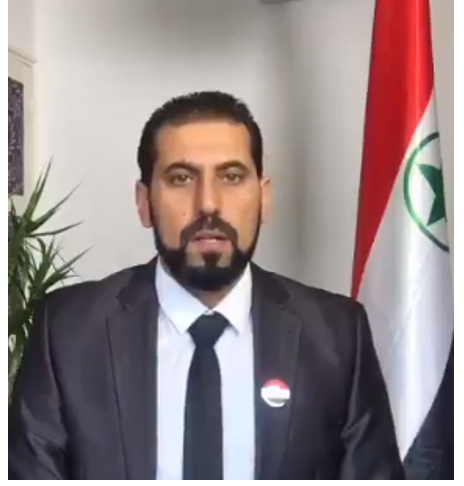

Nissi’s faction elected Saddam Hattem as his replacement in June 2018. Hattem has pledged to continue Nissi’s mission of hosting democratic leadership elections and uniting groups opposed to the Persian occupation of Khuzestan. Ahwazi, Baluch, and Syrian Arab groups attended the first ASMLA conference hosted by Hattem in 2019.

Goals

The ASMLA’s founding mission was to end the Iranian occupation of Khuzestan, which began when the Pahlavi dynasty dissolved the region’s semi-autonomous Arab emirate in 1925. The movement seeks to establish the independent state of Ahwaz. The group defines Ahwaz as the historically Arab territory of Khuzestan province. The ASMLA considers Ahwaz’s borders to be the Zagros Mountains to the north and east, the Persian Gulf to the south, and Iraq to the west. The ASMLA identifies Arabism and religion as the two most prominent components of Ahwazi society. It advocates a democratic state that respects the Arab identity of its citizens and upholds freedom of religion for Sunni, Shiite and Christian Ahwazis.

The flag of "Arabistan" has been used by ASMLA and other Ahwazi groups.

The ASMLA has pursued separatism through “revolutionary and mass struggle” to “restore land, sovereignty and usurped rights in Al-Ahwaz from the clutches of the brutal Iranian occupation.” The group has accused the Islamic Republic of genocidal policies against Ahwazi Arabs. It has condemned the displacement of Arab citizens, the banning of Arabic language in schools, and government-backed resettlement campaigns of non-Arabs in Khuzestan.

The ASMLA has called for cooperation among all non-Persian peoples in Iran. In 2015, Kaabi reported close relations with two anti-government militias—the Baluch Jaish ul Adl and the Kurdish Free Life party. The ASMLA has also called for support from Arab movements abroad. The group has compared the Ahwazi cause to Arab struggles against Iran-backed forces in Syria, Yemen and Lebanon.

Military

The ASMLA began its armed struggle after the 2005 April Uprising. Nissi later claimed that the Martyrs Brigade conducted its first attack in June 2005, which is the same month that Ahwazi militants bombed four government buildings in Khuzestan. The explosions killed eight people and wounded more than 70. The ASMLA also claimed responsibility for a January 2006 bombing that killed at least eight civilians in a bank.

From 2006 to 2011, the ASMLA had a lower profile militarily. In 2012, the group began publishing pictures and reports of attacks on natural gas pipelines. In March, it released a statement that supported the Arab Spring movement and promised “a painful response” to the regime if it continues to mistreat and execute detainees. Since 2013, the ASMLA has claimed at least eight attacks on oil and gas installations and has warned international oil companies against investing in Iran.

In April 2015, the ASMLA escalated military operations to commemorate the 2005 uprising. In April and May, ASMLA fighters killed three police officers and set fire to a government building in Khuzestan. Between 2015 and 2018, the Martyrs Brigade conducted sporadic attacks on security forces.

In September 2018, gunmen killed 25 people and wounded approximately 60 at a military parade in the city of Ahvaz. More than half of the victims were civilians. The government blamed the attack on ASMLA militants linked to U.S. and Israeli intelligence. Kaabi’s spokesperson confirmed that the attackers were Ahwazi separatists but denied prior knowledge of the attack. Kaabi defended the targeting of the Revolutionary Guards as an act of self-defense against a “terrorist militia.” The rival Hattem faction in The Hague also denied a role in the attack and condemned the Kaabi faction for speaking on behalf of the ASMLA.

Foreign Backing

Since 2005, several senior ASMLA members have been granted asylum in Denmark and the Netherlands. Iran has accused both countries of harboring terrorists. In October 2018, Danish intelligence accused Iran of plotting to assassinate three ASMLA members in Copenhagen. An ASMLA spokesperson said that Kaabi was one of the intended targets. The alleged plot was set to take place one year after Nissi’s assassination in The Hague and a month after the Ahvaz military parade shooting.

Iran has long blamed foreign governments for the civil unrest in Khuzestan province. It charged that Britain trained the bombers who attacked oil installations and government facilities in 2005 and 2006. It accused Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates of funding the gunmen who attacked the Ahvaz military parade in September 2018. In February 2020, Danish security forces arrested three ASMLA members—including Kaabi—and charged them with spying for the Saudi government. In June 2020, the Danish Foreign Ministry summoned the Saudi ambassador to discuss the case. “I have made it crystal clear that the Danish government does not accept any terror-related activities on Danish soil,” Foreign Minister Jeppe Kofod said. The ASMLA identifies Saudi Arabia as one of several potential Arab Gulf allies in its struggle against Iran. The movement, however, denies that it is a proxy force for any foreign government.

Farashgard (Revival)

Overview

Farashgard is a political action network that advocates regime change through non-violent civil disobedience. It calls for a secular democratic government and rejects Marxism and clerical theocracy. It recognizes Reza Pahlavi—heir to the exiled Pahlavi monarchy—as “a key figure” in its movement. It claims to have pockets of supporters in Iran, the United States, Canada, and more than a dozen European countries.

Farashgard was founded to unite disparate exiled groups after anti-government protests in December 2017 and January 2018. It encourages Iranians inside the country to peacefully demonstrate against the regime. The group also urges the United States to impose increased economic pressure on the Islamic Republic.

Leadership

Farashgard was established in September 2018 when 40 dissidents published an open letter that called for the non-violent overthrow of the Islamic Republic. Farashgard has a loose organizational structure. Its founding members include monarchists, secular democrats, former political prisoners, human rights activists, artists, academics and journalists. They share goals of secularism, representative governance and support for U.S. sanctions on Tehran.

Pahlavi is Farashgard’s most visible spokesperson. The group’s inaugural public statement described him as crucial to “uniting the secular democratic opposition to the Islamic Republic.” Pahlavi has lived in exile since the 1979 revolution and is a vocal critic of the regime. Since 2001, he has openly called for the unification of pro-democracy opposition groups.

Some Farashgard members have endorsed a constitutional monarchy with Pahlavi as a symbolic figurehead overseeing an elected government. During the protests of 2017 and 2018, demonstrators in at least three cities chanted slogans in support of the former royal family. But the organization does not formally call for a return to monarchy. In interviews in 2001 and 2020, Pahlavi promised to renounce the title of shah if Iranians reject a monarchy after the ouster of the current regime.

Goals

Farashgard’s slogan is to “reclaim Iran and rebuild it.” It rejects political engagement with the Islamic Republic and contends that the government is incapable of reform. It promotes secularism and democracy but does not have a specific vision for a post-clerical government. It promises to support whichever political system the Iranian people vote for after the removal of the theocratic regime.

Farashgard advocates peaceful demonstrations and civil disobedience; it calls on foreign governments to increase pressure on Tehran without resorting to military force. It cites the protests of 2017 and 2018 as evidence that Iranians are prepared for government overthrow. Pahlavi has encouraged the military to defect and unite with grassroots opposition against the regime.

Foreign Backing

Farashgard identifies the United States as the government most capable of accelerating regime change. Pahlavi, who resides outside Washington, has praised President Trump’s campaign to place “maximum economic pressure” on Tehran and was critical of past U.S. efforts to negotiate with the Islamic Republic. Since Farashgard’s founding, Pahlavi has promoted his views at American think tanks and in media interviews.

Jaish ul Adl (Army of Justice)

Overview

Jaish ul Adl (JUA) is a militant Baluchi nationalist organization that promotes Salafi Islam and pursues greater autonomy for Iran’s southeastern Sistan-e Baluchestan province. The JUA splintered from Jundallah in 2012. It emerged after the government’s 2010 execution of Jundallah founder Abdolmalek Rigi and Jundallah’s subsequent decline. Since 2013, the JUA has been the most active Baluchi militant group and has maintained ties to smaller insurgent cells, such as Ansar al Furqan and Harakat Ansar Iran, that emerged out of the original Jundallah network.

The JUA operates in southeast Iran and in Pakistan’s neighboring Baluchistan province. It attacks Iranian security forces in areas with predominately Baluchi populations. The JUA carried out sporadic assassinations and abductions between 2013 and 2017. It intensified its operations in late 2018 with a string of suicide bombings and hostage executions. Like many opposition groups, the number of members in the JUA – and whether they are full-time fighters or part-time volunteers – is uncertain, although the Voice of America and Israel Defense website reported that the group had an estimated 500 members.

Leadership

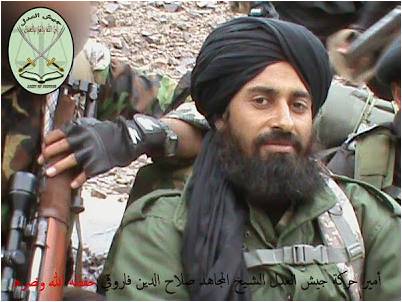

Salahuddin Farooqui (also known as Abdul Rahim Mulazadeh) founded the JUA in 2012. Farooqui and his second-in-command, Mullah Omar (not related to the former leader of the Afghan Taliban), have been the JUA’s most prominent leaders since the group’s inception. Farooqui is from Baluchistan province in Pakistan and has relations with Baluch communities on both sides of the border. Prior to 2012, Farooqui was a Jundallah leader. He recruited several of the JUA’s founding members from Rigi’s former ranks. In 2012, Omar characterized the JUA as a continuation of Jundallah.

The JUA consists of decentralized military branches led by commanders of smaller insurgent groups that have pledged allegiance to Farooqui. Many JUA members are former Jundallah members and have familial or tribal ties to each other. Notable JUA commanders have included two of Rigi’s brothers and Mullah Bux Darakshan. Darakshan is the brother of Mullah Omar and the founder of Jundallah’s predecessor, Sipah e Rasool Allah (SRA).

Goals

In 2015, Farooqui described the JUA as a “defensive military organization designed to safeguard the national and religious rights of the Baluch people and Sunnis in Iran.” The group identifies the government as its primary enemy. The JUA is an ethno-religious group that prioritizes Sunni Baluch freedoms within Iran but also calls for an end to injustices against Sunni Muslims abroad. It has been critical of Iran’s presence in the Syrian War and called for the release of Sunni prisoners held by Iranian forces in Syria during a 2014 hostage standoff.

The JUA’s ambitions appear to align with its predecessors in Jundallah and SRA. The JUA demands greater autonomy in Sistan and Baluchistan and calls for an end to the religious and national oppression of Baluchi Sunnis in Iran. In 2019, the JUA stated that it seeks to “liberate oppressed people of Baluchistan and other compatriots” by “targeting the cadre of [Revolutionary] Guard Corps forces.” JUA leaders have described the group’s mission as a defensive struggle for justice and rights, although the government characterizes the group as a terrorist movement founded to overthrow the Islamic Republic.

The JUA’s ambitions appear to align with its predecessors in Jundallah and SRA. The JUA demands greater autonomy in Sistan and Baluchistan and calls for an end to the religious and national oppression of Baluchi Sunnis in Iran. In 2019, the JUA stated that it seeks to “liberate oppressed people of Baluchistan and other compatriots” by “targeting the cadre of [Revolutionary] Guard Corps forces.” JUA leaders have described the group’s mission as a defensive struggle for justice and rights, although the government characterizes the group as a terrorist movement founded to overthrow the Islamic Republic.

The JUA follows a conservative brand of Sunni Islam, inspired by hardline Salafism and Deobandi revivalism. It considers Sunni Islam to be an integral part of the ethnic Baluch identity, even though a small minority of Iran’s 2 million Baluchis are Shiite Muslims.

Military

JUA’s early attack strategy differed from Jundallah as it did not adopt suicide bombings or target civilian populations. Between 2013 and 2017, the JUA targeted security forces with small arms or conducted kidnappings. It carried out its first major operations in late 2013, killing 14 Iranian border guards and a state prosecutor between October and November. The JUA claimed the attacks were retaliation for the regime’s detention of 16 suspected Baluch fighters on death row.

In February 2014, JUA militants abducted five Iranian border guards and held them ransom in Pakistan for two months. The group demanded the release of 300 Sunnis imprisoned by government forces in Syria and Iran. The JUA released four guards at the behest of prominent Sunni clerics but executed one in captivity.

The JUA carried out a string of deadly attacks between 2017 and 2019. In January 2017, the group claimed that it killed several military personnel—including senior Revolutionary Guard commanders—in the city of Sarbaz, Sistan and Baluchistan province. A JUA spokesperson said the attack was in coordination with the Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Ahwaz, which had recently attacked a natural gas pipeline in Sarbaz. In April 2017, the JUA claimed responsibility for killing 10 border guards near the Pakistani border in Sistan and Baluchistan. Between April and June 2018, the JUA claimed responsibility for attacks that killed at least seven Iranian security force members near the Pakistani border.

In October 2018, the group abducted at least a dozen security personnel in the town of Mirjaveh and held them in Pakistan. The JUA published pictures of the hostages and demanded the release of Baluch prisoners in Iran. Iran and Pakistan secured the release of nine hostages by March 2019, although a Revolutionary Guard Corps general reported that the JUA still held six others.

In February 2019, the JUA launched a suicide attack that killed 27 Revolutionary Guards on a bus between the cities of Zahedan and Khash. Many JUA fighters are seasoned guerilla warriors with training sufficient to engage Iranian forces at close range and attack senior officials. It assassinated a public prosecutor in 2013. JUA has claimed, however, that it will not attack Iranian civilians.

Foreign Backing

JUA’s longstanding presence in Pakistan has complicated relations between Tehran and Islamabad. After JUA’s suicide attack in February 2019, an IRGC spokesperson threatened to deploy forces inside Pakistani territory. In March 2019, Pakistan declared JUA a terrorist group. But Islamabad has historically struggled to control militant activity in the remote mountainous regions of Pakistan’s Baluchistan province.

The Islamic Republic has long accused the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia of covertly supporting Sunni Baluchi terrorism. The government refers to JUA as an organization backed by foreign enemies. U.S. officials reportedly encouraged insurgent activity in southeast Iran as early as 2005, according to an ABC News report in 2007. The Central Intelligence Agency has denied all claims of covert support and classified JUA as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) in July 2019.

Tehran also characterizes JUA as an al Qaeda affiliate. These claims are unsubstantiated, and Farooqui has never pledged support to the al Qaeda network.

Mujahadeen-e Khalq (People’s Holy Warriors)

Overview

The Mujahadeen-e Khalq (MEK) is an exiled militant opposition group that pursues regime change; it calls for a pluralist, secular and democratic Iran but its philosophy has been imbued with both Marxist and Islamist values. Leftist students founded the MEK in 1965 as an urban guerrilla unit opposed to the monarchy. The movement participated in the 1979 revolution but later broke with the government of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini over political and ideological differences. The MEK went into exile in 1981.

In the early 1980s, the MEK united opposition groups under the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI), an umbrella movement with a parliament based in Paris. Beginning in 1985, the MEK – under Massoud and Maryam Rajavi—gradually took control of the NCRI and converted a movement originally made up of diverse opposition groups into an MEK subsidiary. The NCRI parliament also came under their control. Some—including the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan—defected. The MEK’s most active insurgency took place while it was based in Iraq between 1986 and 2003. It has since been limited to isolated sabotage operations inside the country and propaganda campaigns outside the country.

Leadership

The MEK was founded by three students --Mohammad Hanifnejad, Saeid Mohsen, and Asghar Badizegan--at Tehran University in 1965. It promoted a modern interpretation of Shiite Islam that rejected both the monarchy and capitalism. In 1970, the MEK started targeting foreign and domestic supporters of the monarchy. The operations included the assassination of six Americans--three military officers and three civilians—and the attempted kidnapping of U.S. Ambassador Douglas MacArthur. In late 1971, the shah’s secret police thwarted an MEK attack on state power grids; all three founders were executed on May 25, 1972.

After the revolution, Massoud Rajavi built the MEK into one of the country’s most powerful factions, but had a falling out with Khomeini over a new constitution. When the MEK balked at participating in the constitutional referendum, the ayatollah banned the movement from holding office. The deepening divide led members either to move underground or flee the country.

In 1981, the MEK conducted a string of attacks against top Iranian officials. One bombing at the headquarters of the Islamic Republican Party in June killed 74 government officials, including the chief justice and twenty-seven members of parliament. A second bombing in August killed the president, prime minister and six other officials. The regime responded with prosecutions and mass executions of suspected MEK members.

From exile in Paris, Rajavi co-founded the National Council of Resistance with Abdolhassan Banisadr, the Islamic Republic’s first president who was impeached in June 1981. Rajavi and Banisadr fled the country secretly together in July. Massoud married Maryam Qajar-Azodanlu in 1985. She had been a social organizer for the MEK in the 1970s and a founding member of the NCR. She became president of the NCRI in 1993. The MEK adopted a cult-like structure under their joint leadership. The Rajavis were evicted from France in 1986 and set up new headquarters in Iraq. They served as co-leaders until 2003.

In the late 1980s, loyalty to the MEK became synonymous with loyalty to the Rajavi family. The Rajavis imposed harsh initiation requirements on recruits, including mandatory divorce, celibacy and the confiscation of assets. MEK defectors and human rights monitors have accused the Rajavis of crimes against humanity, including ethnic-based violence and the systematic sexual abuse of members. Massoud has not been seen since the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. The MEK has claimed that he is in hiding, although his whereabouts are uncertain. Maryam Rajavi assumed sole leadership of the MEK. Since 2003, Rajavi, as head of the NCR, has been based in Paris.

Between 2003 and 2012, the organization renounced violence and successfully sued for removal from the U.S. and E.U. lists of foreign terrorist organizations. For several years, the NCRI has held annual conferences advocating for regime change in Iran. Other long-term NCRI members, including women, have risen to leadership roles. Zahra Merrikhi became the Secretary-General of the MEK in 2017. Many women also once served as senior officers in its militia.

Goals

The early MEK philosophy blended Marxist egalitarianism, Shiite Islamism and Iranian nationalism. Its founders advocated a society that retained its Shiite Muslim identity but opposed imperialism, Islamic fundamentalism and foreign corporations in Iran. The Rajavis continued to promote democratic pluralism during the MEK’s exile in France and Iraq, but downplayed the group’s Marxist influence to avoid tensions with potential Western allies. The Rajavis also made gender equality a central tenet of the MEK philosophy.

In 2013, Maryam Rajavi published a 10-point manifesto. The document called for a pluralist democratic system, separation of religion and state, abolition of the death penalty, gender equality, and adherence to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It also embraced a market economy and the right to private property and private investment. It vowed a non-nuclear Iran free of weapons of mass destruction.

Military

The MEK claimed hundreds of thousands of supporters before its exile in 1981. Membership numbers before exile, however, are uncertain. After the MEK’s expulsion from France in 1986, approximately 7,000 members—an estimated 80 percent of the group’s membership in exile—moved their operations to Iraq.

Iraqi President Saddam Hussein armed the MEK’s National Liberation Army and used its fighters as an unofficial wing of the Iraqi military in the final two years of the war with Iran. After Iran accepted a U.N. ceasefire in July 1988, the MEK launched Operation Eternal Light, an assault with some 7,000 fighters in Kermanshah Province to incite a popular uprising. It failed. Iranian forces killed between 1,200 and 2,000 MEK fighters, then arrested and executed thousands of suspected MEK members at home.

Iraqi President Saddam Hussein armed the MEK’s National Liberation Army and used its fighters as an unofficial wing of the Iraqi military in the final two years of the war with Iran. After Iran accepted a U.N. ceasefire in July 1988, the MEK launched Operation Eternal Light, an assault with some 7,000 fighters in Kermanshah Province to incite a popular uprising. It failed. Iranian forces killed between 1,200 and 2,000 MEK fighters, then arrested and executed thousands of suspected MEK members at home.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the MEK carried out sporadic acts of violence, including a raid by supporters armed with knives and firebombs on Iran’s U.N. Mission in New York in 1992. The NCRI also exposed details of Tehran’s secret nuclear operations. In 2002, it revealed information on the government’s uranium enrichment program at Natanz that triggered a U.N. investigation. MEK operatives—with training, funding and logistical support from Israel’s Mossad--were linked to the assassination of five Iranian nuclear scientists between 2007 and 2012. The MEK denied the allegations.

After Saddam’s ouster in 2003, the MEK accepted a ceasefire with U.S. forces that disarmed the group. The approximately 3,800 remaining MEK members in Iraq were allowed to remain in their own camp under U.S. military protection. MEK fighters were moved to other countries between 2012 and 2016. The largest group was moved to Albania.

Foreign Backing

Since 1981, the MEK has depended on support—logistical, financial, political or military—from foreign countries. From 1981 until 1986, the leadership was based in France. Between 1986 and 2003, the MEK leadership operated out of Iraq, with troops remaining in Iraqi camps until 2016. Since the group’s removal from the E.U. list of foreign terrorists in 2009, MEK leaders have again organized publicly in France.

U.S. views of the MEK have changed over time. In 1997, the Clinton Administration added the MEK to the list of foreign terrorist organizations; the European Union followed suit in 2002. In June 2003, the French government arrested more than 150 MEK members, including Maryam Rajavi, on suspicion of financing terrorism. The arrests sparked MEK protests in Europe and Canada, which included several self-immolations.

In 2003, the United States—as the occupying power in Iraq--granted MEK members “protected persons” status under the terms of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Between 2004 and 2012, the MEK was both a designated terrorist organization and protected by the U.S. military. When U.S. forces withdrew from Iraq in 2011, Iran-backed militias in Iraq killed dozens of MEK members at Camp Asharf. The United States removed the MEK from its terrorist list in 2012 and facilitated the relocation of its last forces to Albania in 2016.

Since 2012, multiple American public figures—including former National Security Advisor John Bolton and former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani—have endorsed the MEK as an alternative to the present regime. Past speakers at MEK events include a bipartisan cross-section of former U.S. officials.

Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan

Overview

The Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI) is a banned Kurdish militant group that operates in northern Iraq and in Kurdish towns along Iran’s western border. The PDKI pursues Kurdish self-determination and national rights within a federal and democratic Iran. Founded in 1945, the PDKI was primarily an underground organization between the execution of founder Qazi Muhammad in 1947 and the Iranian Revolution in 1979. It spent the mid-20th century navigating strategic partnerships with other Kurdish groups amid severe crackdowns by the shah, with the exception of a brief resurgence during the Mossadegh government between 1951 and 1953.

The KDPI participated in the 1979 revolution but failed to secure self-determination for Iran’s Kurdish regions. The group launched the unsuccessful 1979 Kurdish Rebellion in March, one month before the formal establishment of the Islamic Republic. Ayatollah Khomeini issued a religious edict against the KDPI’s leadership in August 1979 and forced most of the group into exile in Iraqi Kurdistan by 1984.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the group carried out sporadic insurgent attacks across the border. Two PDKI leaders were assassinated, one in Vienna in 1989 and another in Berlin in 1992; the movement blamed Tehran. In 1996, the PDKI declared a unilateral ceasefire. For two decades, it was largely dormant. In 2006, it splintered, more over personal than ideological differences. In 2016, the PDKI launched a new offensive with small-scale attacks on government forces along the border with Iraq that continued sporadically into 2020.

Leadership

In 1945, Qazi Muhammad founded the PDKI as a Kurdish separatist organization and declared independence from Iran. For several months, he served as president of the short-lived Independent Kurdish Republic of Mahabad, based in the northwest city in West Azerbaijan province. It received financial and political backing from the Soviet Union. The government quashed the secession movement in 1946 and hanged Muhammad in March 1947.

Mustafa Hijri Spoke to the Kurdish Nation: https://t.co/FirnM0qwXX #Peshmerga #TwitterKurds #Kurdistan #Iran #PDKI pic.twitter.com/eoi8z2l1Re

— PDKI (@PDKIenglish) June 18, 2016

Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou was elected Secretary-General of the PDKI in 1973. Between April and August 1979, Ghassemlou supported Kurdish autonomy in a federated Iran and rejected separatism. He ran for elected office in the new Islamic Republic but also supported the PDKI’s ongoing Kurdish Rebellion. Khomeini declared Ghassemlou an enemy of the Islamic Republic in August 1979. Between 1981 and 1985, Ghassemlou supported the PDKI’s membership in the National Council of Resistance, the Mujahadeen-e Khalq’s revolutionary parliament in exile. In July 1989, Ghassemlou was assassinated in Vienna after a round of peace talks between the PDKI and the Islamic Republic.

The current leader is Mustafa Hijri, who was elected secretary-general by the PDKI congress in 2006. Hijri had demonstrated against the monarchy in the Iranian Revolution. He led in various capacities between 1979 and 2006, including three years as the interim party leader after the 1992 assassination of Secretary-General Sadegh Sharafkandi--Ghassemlou’s successor—in Berlin. In 2007, he supported the PDKI joining the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO).

The PDKI’s highest decision-making body is its congress, which is designed to be held every four years. The congress elects a Central Committee of 25 members as well as a seven-person Political Bureau. The Political Bureau includes the secretary-general and functions as an executive cabinet. Affiliated organizations include the Democratic Women’s Union of Iranian Kurdistan, the Democratic Youth Union of Kurdistan, and the Democratic Students Union of Kurdistan. It supports multiple youth organizations in Kurdish towns to cultivate rising leaders.

Goals

The PDKI’s ideology is based on democratic socialism and Kurdish nationalism. It prioritizes “an explicit commitment to democracy, liberty, social justice and gender equality.” The group is a member of the Socialist International.

In 2004, the PDKI shifted its mission from total independence from Iran to support for a federal democratic system that gave autonomy to the Kurds within Iran. Hijri did not, however, disavow military operations. In 2016, he announced the Rasan campaign against the “theocratic tyranny” of the Islamic Republic. Hijri stated that the campaign’s goal was to “achieve [national] rights within the framework of a united Iran,” by “sending squads and cells from our Peshmerga forces into Iranian Kurdistan, to carry out operations against the IRGC.” Rasan has also involved online propaganda and education programs in Kurdish townships on Iran’s western border.

Military

During the Kurdish Rebellion—the largest uprising after the revolution—the PDKI claimed more than 7,000 fighters. The conflict killed an estimated 10,000 people and displaced 200,000. The rebellion ended in 1981 with the dissolution of the united Kurdish military opposition in Iran. The PDKI continued insurgent activities with material support from Iraq, but its campaign fizzled by 1983 and the group gradually relocated to northern Iraq.

The PDKI revived the insurgency after Ghassemlou’s assassination in 1989. Kurdish rebels clashed with government soldiers near northwestern Mahabad. Almost 500 Iranian forces were killed during Kurdish attacks in 1989 and 1990, according to historic accounts. In January 1991, the government executed seven PDKI members on charges of spying and murder. A guerilla insurgency persisted for the next five years.

In 1992, the PDKI’s resistance in Iran began to disintegrate due to increased Turkish support for Iranian counterinsurgency operations and Sadegh Sharafkandi’s assassination, which devastated the group’s leadership structure. In 1993, Tehran bombed PDKI targets in the no-fly zone established by U.S. coalition forces in Iraqi Kurdistan. The PDKI abandoned bases in the Qandil Mountains of Iraq’s northern Kurdistan and moved southward. Since the mid-1990s, it has been primarily based in Erbil province’s Koy Sanjaq district—approximately 40 miles from the Iranian border. The PDKI entered into a de facto ceasefire with the Islamic Republic between 1996 and 2016.

In 2016, Hijri restarted the PDKI’s armed resistance by announcing the Rasan—or “Uprising”—campaign. In June 2016, PDKI fighters clashed with security forces in an Iranian Kurdish near the Iraq border. The PDKI claimed to kill 20 Iranian soldiers, and the government reported 11 PDKI fighters killed. Since the beginning of Rasan, the government has sporadically attacked suspected PDKI strongholds in Iraq. An Iranian airstrike in September 2018 killed fifteen Kurdish Peshmerga members in the Iraqi town of Koya.

The PDKI has denied any affiliation with the Zagros Eagles, a militant Kurdish faction, despite published reports of possible ties. The Zagros Eagles carried out offensive operations against Iranian forces between 2016 and 2018 that killed at least eight soldiers. The PDKI reported these attacks but said that they were separate from its Rasan campaign of defensive resistance.

Since the 1990s, the PDKI’s primary headquarters have been in the Koy Sanjaq district of Erbil province in Iraq; Koy Sanjaq is approximately 40 miles from the Iranian border. It is estimated to have between 1,000 and 2,000 fighters spread across the remote Iraq-Iran borderlands.

Today marks the Peshmerga Forces Day! https://t.co/2qusEcl9k6 pic.twitter.com/F6SKQ30jfF

— PDKI (@PDKIenglish) December 17, 2019

Foreign Backing

Since the early 1980s, the PDKI’s survival has depended on positive relations with its Kurdish brethren in Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). But the PDKI has also tried to avoid military activity that provokes Iranian intervention in Iraq—as it did during the Rasan campaign in 2018 when Iran launched an airstrike in Koya, Iraq against PDKI targets.

Casey Donahue is a research assistant at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, which co-sponsors "The Iran Primer" with the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Photo Credits: Saddam Hattem via Twitter; Reza Pahalvi byGage Skidmore / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0); Emblem is the work of the People's Mujahedin of Iran. SVG by MrPenguin20 / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0); Maryam Rajavi via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)