How much does Iran spend on its military? How has defense spending changed over the past two decades?

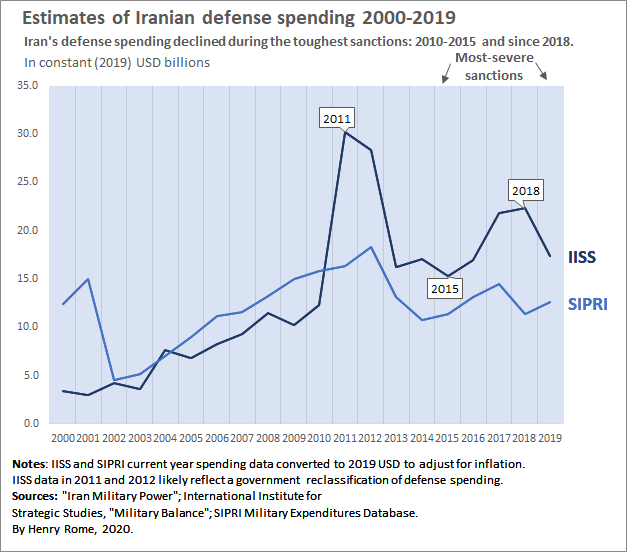

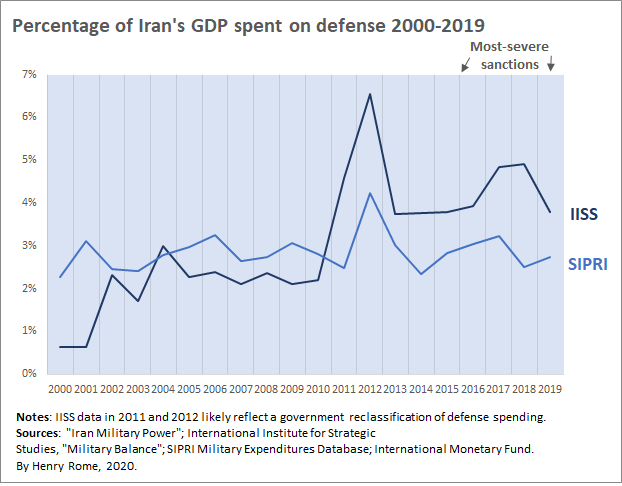

Between 2015 and 2019, Iran annually spent 4 percent to 5 percent—or $18 billion to $22 billion—of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense. Defense spending was around $18.4 billion in 2019, although the precise value is contested, given the opacity of the Iranian system and disagreements over what funding constitute defense spending, as reflected in these different estimates for 2019:

- The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimated $12.6 billion;

- The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) estimated $17.4 billion; and

- The U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) reported $20.7 billion.

Defense spending has tracked closely with the intensity of U.S. and multilateral sanctions. Defense budgets fell steadily in the early 2010s as the United States and the international community increased pressure on Tehran, which limited its oil revenues and sent the economy into recession. Iran ramped up spending after the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Between 2016 and 2018, defense spending increased by more than 30 percent to one of the highest levels in at least two decades.

In 2019, Iran significantly reduced defense spending after the U.S. withdrew from the nuclear accord. The re-imposition of U.S. sanctions drove the economy back into recession and significantly weakened the rial. In contrast, defense spending in the 2020 budget is estimated to be $20.5 billion. The increase—amid the pandemic and an economic crisis—illustrated the government’s enduring commitment to funding institutions used for suppression at home and intervention abroad.

The diverse wings of the Iranian military have other resources, however. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), in particular, has off-book revenues from private companies it controls in the construction, energy, and transportation sectors, among others. The IRGC also has a leading role in helping the government and businesses evade U.S. sanctions in international trade; its smuggling operations provide a significant additional revenue source.

The charts below show the past two decades of Iranian defense spending, first in dollars (adjusted for inflation) and then as a percentage of GDP, according to diverse sources.

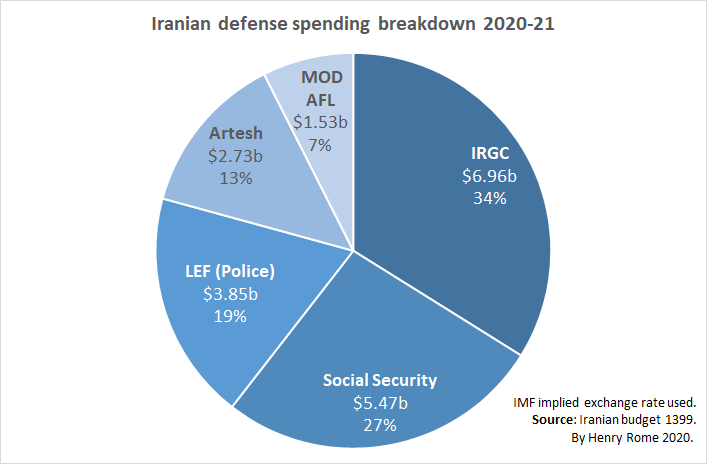

How does Iran divide funding between its conventional military, the IRGC, and other components of the military?

In the 2020 budget, the IRGC received $6.96 billion, while the larger conventional military—known as the Artesh—received $2.73 billion. The difference in funding reflects the IRGC’s importance as a political, military, ideological and economic actor. For decades, the Artesh has been at a distinct disadvantage on resources, choice of recruits and political influence. (The difference between the two militaries was on display in early June 2020, when the deputy commander of the Artesh publicly criticized the IRGC for showboating and promoting its own interests.)

Iran’s military strategy is framed around asymmetric warfare and emphasizes proxy conflicts, irregular naval tactics, a robust ballistic missile program, and cyber operations. The IRGC is the dominant player in all four of those arenas, while the Artesh is built like a traditional conventional military and operates outdated tanks, ships, and aircraft. This year’s budget showed that the funding gap between the IRGC and the Artesh gap is getting wider. In 2019-20 and 2018-19, the IRGC budget was two times larger than the Artesh, while in 2020, it was two-and-a-half times larger.

The defense establishment also includes the Law Enforcement Forces (LEF) and the Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL). The LEF is the country’s national police force, while the MODAFL is responsible for overseeing the defense industry. The Armed Forces Social Security Organization is the pension fund for the military. The Basij, the voluntary paramilitary organization, is part of the IRGC.

Where does Iran procure arms, and how important is its home-grown defense industry?

Even before the 1979 revolution, Iran sought to develop an indigenous defense industry, both as an insurance policy against unreliable foreign suppliers and as a way to showcase its technical acumen. Iran’s defense industrial base has developed new and advanced weapons, such as unmanned aerial vehicles and ballistic missiles. It also procures and produces the spare parts needed to maintain its legacy systems, including its fleet of U.S.-manufactured fighter jets purchased before 1979.

In the first three decades after the revolution, Iran bought weapons system—including submarines, Scud-B missiles, and missile boats—primarily from Russia, China, and North Korea. It worked to reverse-engineer and upgrade these and other foreign acquisitions. But in 2010, acquisitions abroad dried up after passage of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1929, which banned the sale of major arms to Tehran.

The JCPOA—endorsed unanimously by the Security Council in U.N. Resolution 2231—stipulated that the arms embargo would expire in October 2020. But the Trump administration opposed lifting the embargo and threatened to invoke the provision for the “snap back” of all U.N. sanctions. Iran has viewed the end of the embargo as one of the last remaining benefits of the JCPOA. If the embargo lapses, however, the history and structure of Iran’s defense strategy suggests that it would not necessarily go on an international arms shopping spree. Iranian military leaders are constrained by cost and driven by a desire to transfer technology to the domestic industry. Instead of buying large fleets of new tanks or fighter jets, Iran is more likely to purchase small numbers of advanced weapons systems and ensure the technology is transferred domestically.

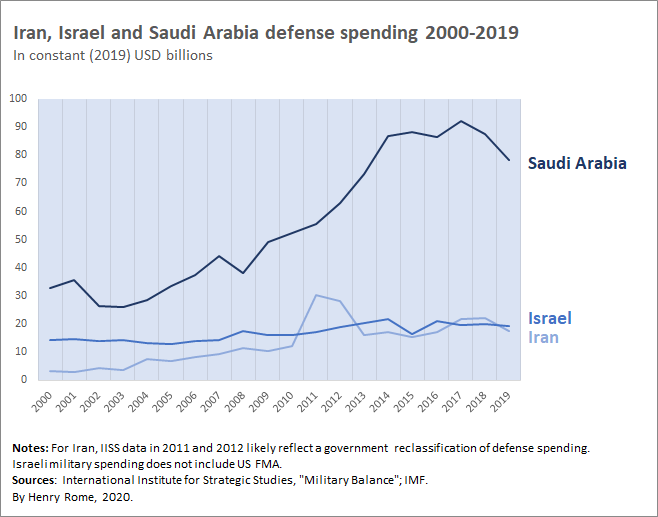

How does Iran’s military spending compare to its regional rivals and to world powers?

Iran’s two main regional rivals have significantly different approaches to military spending. Saudi Arabia spends the most on defense in the region and the third-most in the world, behind the United States and China. In 2019, Saudi Arabia spent nearly $80 billion on defense, the same as Iran spent over the previous four years combined, according to the IISS. Iran spent 3.8 percent of GDP on defense in 2019, while Riyadh spent more than 10 percent. (Only two other countries spent more of their GDP, proportionately, than Saudi Arabia: Oman and Afghanistan). In many ways, Iran and Saudi Arabia are opposites in how they acquire weaponry. Since the revolution, the Islamic Republic has made modest foreign purchases and relied on its domestic industry for defense technology, while Saudi Arabia is the world’s largest importer of arms.

In numerical terms, Iran’s defense budget more closely resembles Israel’s expenditures. In 2019, Iran spent $17.4 billion—or 3.8 percent of its GDP—while Israel spent $19.3 billion—or 5 percent of its GDP—on defense, according to IISS data. Like Iran, Israel has a robust indigenous arms industry, which grew out of necessity because of its isolation in its early decades, although Israel’s defense corporations are now well integrated into the global arms market. Israel’s domestic capabilities are also now supplemented by its close relationship with the United States. The U.S. provides Israel more than $3 billion annually in additional military financing, which makes up the majority of the military’s procurement budget.

Iran’s military spending is far less proportionately than the United States, Russia or China. In 2019, the U.S. military budget was more than 30 times larger than Iran’s. As a share of GDP, Iran spends as much as Russia on defense, according to the IISS. They both spent 3.8 percent of their GDP. In contrast, the United States spends about 3.2 percent of GDP on defense, and China spends 1.3 percent.

Henry Rome is the senior Iran analyst at Eurasia Group.