Kevan Harris

- Iranian bazaars, especially Tehran’s Grand Bazaar, have played central roles in the economic and political history of the country. “Bazaari” is a term applied to Iran’s heterogeneous commercial class located in historical urban centers.

- Bazaaris have often allied with other social groups, including the clergy, in anti-government protests when their grievances have overlapped.

- Under the Pahlavi monarchy, the bazaar prospered as an institution because of state neglect. But under the Islamic Republic, individual bazaaris were given key positions of power.

- Bazaaris have adapted to the new constraints that a state-dominated economy have created and the opportunities that a global economy has provided. They have contributed to and benefited from diversification of Iran’s economy.

- There is no such thing as a single “bazaari mentality,” since bazaars reflect and respond to the political and economic developments of contemporary Iran.

- Bazaaris have gradually lost influence in recent years due to commercial restructuring in retail and wholesale chains as well as changing consumption patterns.

Overview

Bazaars in Iran are more than local markets for the truck and barter of traditional goods and handicrafts. They are urban marketplaces where national and international trade is conducted, political news and gossip is shared, religious and national symbols are on display and various social classes mingle. Iran’s largest bazaar, located in central Tehran, has been central to the country’s economic and political history since the late 19th century, most notably as a major force in the 1979 revolution.

The bazaar has long occupied the imagination of intellectuals, politicians, and travelers inside and outside Iran. For many, its customs and attitudes represent the traditional qualities of the nation’s culture. One frequently hears the need to understand “the bazaar mentality” in analyses of Iranian statecraft and foreign policy. In reality, however, bazaars in Iran have continually changed with the times.

Under the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, bazaars benefited from a long period of economic growth, but they were also alienated by the monarchy’s rapid modernization agenda. After the 1979 revolution, individual supporters of the Khomeini-led government from the bazaar were given more control over commerce and trade, but increased state management of the economy and an unpredictable investment environment did not benefit the bazaar as a whole. The links between Iranian bazaars and the international economy are densely connected, as smuggling through the United Arab Emirates and other Middle East entrepôts (trading posts) created major routes to supply domestic consumers with cheap East Asian goods. As urban areas have grown, commercial shopping areas well beyond the downtown bazaar have emerged to meet the desires of Iran’s new middle classes. Instead of being a bastion of tradition that represents an ancient way of life, the bazaar in contemporary times is remarkably different than in previous periods of Iranian history.

Under the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, bazaars benefited from a long period of economic growth, but they were also alienated by the monarchy’s rapid modernization agenda. After the 1979 revolution, individual supporters of the Khomeini-led government from the bazaar were given more control over commerce and trade, but increased state management of the economy and an unpredictable investment environment did not benefit the bazaar as a whole. The links between Iranian bazaars and the international economy are densely connected, as smuggling through the United Arab Emirates and other Middle East entrepôts (trading posts) created major routes to supply domestic consumers with cheap East Asian goods. As urban areas have grown, commercial shopping areas well beyond the downtown bazaar have emerged to meet the desires of Iran’s new middle classes. Instead of being a bastion of tradition that represents an ancient way of life, the bazaar in contemporary times is remarkably different than in previous periods of Iranian history.Bazaar history

Like the Athenian agora, the Arabic souk, or European fairs of trade, the Persian bazaar is central in understanding the development of political dynasties and economic enterprise in those areas where they contribute to daily life. Notable pre-Islamic bazaars appeared in Bukhara and Khuzestan, and bazaar layouts adapted urban innovations from Roman and Byzantine cities.

By being situated at the major nodes of regional and global trade routes, merchant families accumulated wealth, prestige and power. In doing so, bazaars also became central locales of political organization in supporting or opposing the many rulers of Iran. The concentration of merchants, middlemen and wholesalers in densely packed alleys under covered roofs created a social space where common grievances could quickly coalesce, even between rich merchants, poor workers and diverse ethnicities.

The bazaaris of Tabriz and Isfahan who took part in the 1905-1911 Constitutional Revolution became local legends, and many Tehran bazaaris supported Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in his attempt from 1951 to 1953 to nationalize the production of Iranian oil away from foreign control.

The revolution

The Pahlavi monarchy cared little for bazaars, preferring modern shopping centers and channeling financial support to heavy industry. But the oil-fueled economic growth of the 1960s and 1970s still benefited the bazaar. The shah mostly neglected the 100,000 merchants and workers and 20,000 shops in the Tehran bazaar until 1975, when the state initiated an anti-profiteering campaign and price controls against bazaar shops.

The disparate political tendencies of various bazaar merchants soon united against the shah’s government. Bazaaris participated in and supported protests and demonstrations in the spring of 1977, well before most social groups—including the clergy—had joined the revolutionary surge.

Bazaaris and clerics

Although bazaaris eventually mobilized through local mosques during the revolution, this temporary partnership did not turn into a permanent bazaar-mosque alliance as the political backbone of the Islamic Republic. During the 1980s war years, the state nationalized major industries, restricted trade and controlled credit. Key bazaari supporters of the Khomeini regime were given high positions in government and rewarded with coveted import licenses.

Although bazaaris eventually mobilized through local mosques during the revolution, this temporary partnership did not turn into a permanent bazaar-mosque alliance as the political backbone of the Islamic Republic. During the 1980s war years, the state nationalized major industries, restricted trade and controlled credit. Key bazaari supporters of the Khomeini regime were given high positions in government and rewarded with coveted import licenses. Yet the prolonged turmoil and uncertainty severely hindered the ability to export Iranian goods to lucrative Western markets, or privately engage in long-term planning for the domestic market. As a result, many bazaaris felt detached from their supposed representation—the conservative Motalefeh faction—in government.

Today, there are indications that many bazaaris have been disenchanted with the Islamic Republic’s policies for quite some time. Anecdotal evidence shows that many voted for Mohammad Khatami in 1997 and 2001, and also Mir Hossein Mousavi in 2009. Hassan Rouhani attracted pro-business voters in the 2013 presidential election, but bazaaris did not back any one candidate. However, compared to students, workers and women, bazaaris have rarely protested in public against the regime, even when other groups took to the streets.

This seemingly changed in October 2008 and again in July 2010, when bazaars in major Iranian cities closed down in protest over the Ahmadinejad government’s attempts to collect more taxes from bazaar shops. Both protests resulted in the government backing down to the demands of the bazaaris.

Yet the absence of bazaari activity during the Green Movement demonstrations of June and July 2009 indicates that broader links between the bazaar as a social entity and democratic social movements in Iran have not developed. This is perhaps because bazaars today seldom exhibit the collective identity and public solidarity that occurred in past moments of Iranian political history. This stems partially from the new cleavages in bazaar networks that resulted from the Islamic Republic’s management of the economy and the picking of politically subservient economic winners. However, it also derives from significant changes in relations between the bazaar and the global economy.

The bazaar and globalization

Many bazaar merchants are still wealthy, but networks of Iranian commerce and trade have shifted in the past 30 years, reducing the bazaar’s central importance to economic life. Both legal and smuggled imports entered the country through major ports such as Bandar-e Abbas or free trade zones such as the islands of Kish and Qeshm. As East Asian merchandise rose in quality and lowered in price, it easily outsold Iranian-manufactured products inside the country. An expanded and educated Iranian middle class preferred international goods that reflected Western prestige and status, even in knockoff form. A small but growing number of superstores and shopping malls exist in Iran. And increasing urbanization and congestion have meant that fewer wealthy Iranians living far from downtown are willing to travel to the bazaar to make major purchases.

Many bazaar merchants are still wealthy, but networks of Iranian commerce and trade have shifted in the past 30 years, reducing the bazaar’s central importance to economic life. Both legal and smuggled imports entered the country through major ports such as Bandar-e Abbas or free trade zones such as the islands of Kish and Qeshm. As East Asian merchandise rose in quality and lowered in price, it easily outsold Iranian-manufactured products inside the country. An expanded and educated Iranian middle class preferred international goods that reflected Western prestige and status, even in knockoff form. A small but growing number of superstores and shopping malls exist in Iran. And increasing urbanization and congestion have meant that fewer wealthy Iranians living far from downtown are willing to travel to the bazaar to make major purchases.Bazaaris have accustomed themselves to challenges posed by US and European-led sanctions. Exports and imports have shifted to countries such as China, India, Brazil, and other places that either passed no sanctions on Iran or enforced them grudgingly. For example, the chador, a full body covering for women, is often produced today using imported cloth. Sanctions did not significantly hamper exports from 2006 to 2011, but commercial trade and domestic production suffered from 2011-13. Instead of Europe, Iran exported to China, India, Russia, Central Asia, Turkey and elsewhere. Sanctions had a large impact on how bulk commodities were imported and exported. For businesses, sanctions added a layer of costs and logistical difficulties to simply get products over the country’s borders.

Nevertheless, Iranian merchants have figured out ways to import difficult to procure goods. Many bazaaris work with fellow Iranians in Persian Gulf entrepots such as Dubai or Muscat, for example, to ship a wide variety of fashionable products to their stores. They maintain necessary contacts with important individuals in government ministries and agencies, in order to acquire goods in a timely manner.

Commercial profits in the bazaar are mostly short-term and precarious. And there is a high incentive to transfer wealth out of the bazaar and into speculation on land and real estate, which many bazaaris have done since the 1980s. While Iran’s urban bazaars may have more employees, stores and goods now, compared to before the revolution, their social role and centrality to the country have diminished. Iranians have many more options in terms of places to shop, including chain stores and mega malls.

Romanticizing the bazaar

European visitors to Iran since the 16th century have identified the bazaar with the traditional culture of the country, conjuring up notions of piety, honesty and community on the one hand, shiftiness, gluttony and irrationality on the other. Many commentators on Iran today still lamentably employ timeless and hackneyed descriptions of a “bazaar mentality” to explain everything from Iranian statecraft to Persian literature and films. These clichés are not only insulting but also empirically inaccurate, given the adaptation and diversity within bazaar networks over the arc of modern Iranian history.

European visitors to Iran since the 16th century have identified the bazaar with the traditional culture of the country, conjuring up notions of piety, honesty and community on the one hand, shiftiness, gluttony and irrationality on the other. Many commentators on Iran today still lamentably employ timeless and hackneyed descriptions of a “bazaar mentality” to explain everything from Iranian statecraft to Persian literature and films. These clichés are not only insulting but also empirically inaccurate, given the adaptation and diversity within bazaar networks over the arc of modern Iranian history.Bazaaris are losing influence but still have access to prime real estate in the center of cities. In the future, Iran’s bazaars may be transformed into symbolic sites of nostalgia. Or they may be renovated into refurbished urban commercial zones, a transformation already occurring in the bazaars of Mashhad and Tabriz.

Factoids

- Iran’s Taskforce to Combat the Smuggling of Goods and Foreign Currency estimated the amount of goods smuggled into the country, often to avoid state tariffs on imports, at over $20 billion USD a year (around 5 percent of GDP in 2014). The Ministry of Trade listed the top goods smuggled into the country as gold, clothing, home appliances, cellphones, computers, cosmetics, and cigarettes.

- Tensions between the bazaar-founded Motalafeh coalition and the Ahmadinejad government were strong. The coalition did not back a candidate in the 2013 presidential election.

- Resalat is a conservative newspaper associated with the Motalefeh faction. It frequently features opinion pieces on the Iranian economy arguing for more laissez-faire policies that would remove state tariffs and regulations on trade, and benefit the bazaar.

- Bazaari merchants and their employees are now eligible to enroll in the Social Security Organization’s self-employed pension program, one of the most generous pensions in the world for retirees.

The fate of bazaars is unclear as cities grow and develop. Consumers have increasingly more choices for places to buy goods.

Individuals and organizations

- Islamic Coalition Association (Jamiyat-e Motalefeh-e Islami or ICA) is a pro-Khomeini opposition group that originated in the bazaar in the early 1960s. It had to compete with other well-organized oppositional groups in the bazaar, including the Liberation Movement of Iran associated with Mehdi Bazargan. After 1979, ICA members were placed in high government posts and took staunchly conservative positions in factional battles.

- Habibollah Asgarowladi, who passed away in 2013,was from a bazaar merchant family. He was a founding member of the ICA, served as minister of commerce (1981 to 1983) and was the supreme leader’s representative in the Imam Khomeini Relief Committee. He helped other ICA members get top positions in state-created Centers for Procurement and Distribution of Goods during the Iran-Iraq War. A wide range of top officials attended his funeral, including President Hassan Rouhani, Parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani, Judiciary Chief Sadegh Amoli Larijani and Assembly of Experts Chairman Mohammad Reza Mahdavi-Kani. Still an important voice in conservative politics today, his brother Asadollah is director of the Iran-China Joint Chamber of Commerce and the Iran-Russia Joint Chamber of Commerce.

- Mohsen Rafiqdoust joined the ICA as a teenager while working in the vegetable bazaar. He was nicknamed the “Imam’s driver” because he picked up Khomeini from the airport in Tehran upon his arrival from exile in February 1979. He later became the Revolutionary Guards minister and then the head of the Foundation for the Oppressed and Disabled, a large state-funded charity, in the early 1990s. He faced widespread charges of embezzlement and mismanagement. Reportedly one of the richest men in Iran, he is now active in the private sector.

- Iran’s Chamber of Commerce, Mines, Industries, and Agriculture includes former bazaar merchants and representatives of the commercial sector. A previous head, Mohammad Nahavandian, became the chief of staff of President Hassan Rouhani. The Chamber represents industry and manufacturing as well, which has led to conflicts over state tariffs and investment between the import-dependent bazaars and domestic producers.

Trendlines

- Deeper government encroachment or further economic deterioration could lead protest within the bazaar once again.

- Yet the bazaar is unlikely to be a potent force in politics, due to multiple cleavages in bazaar networks and dependence on the state for livelihoods. These divisions are likely to widen even if sanctions are lifted as part of the nuclear deal.

- Merchants have to compete with the finance and real estate sectors in a larger way than before.

- Privatization of state-owned companies in Iran has been transferred mostly to state-linked organizations, pension funds, and notable elites in an opaque manner. As an institution, the bazaaris have been largely excluded from this process, while individuals may be getting involved through other channels.

Kevan Harris is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

This chapter was originally published in 2010, and is updated as of November 2015.

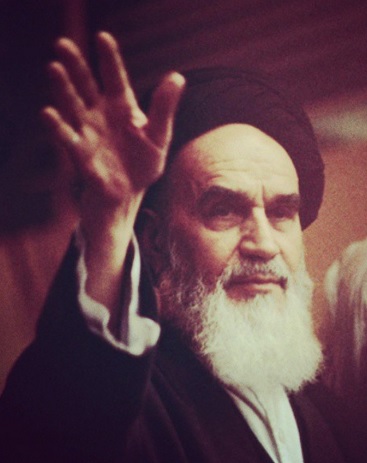

Photo credits: Tehran bazaar by Maral Noori; Isfahan Royal Mosque by Patrickringgenberg (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons; Imam Khomeini via Instagram; Tiraje Mall in Tehran by Mehrad Afkham via Panoramio [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]; Tehran Bazaar by Babak Farrokhi via Flickr Commons (CC BY 2.0)

Economy_Harris_Bazaar 2015.pdf211.25 KB