The Houthis are a political movement and militia that emerged out of a religious revival among Yemen’s Zaydi Shiites in the 1990s. They got their name from a powerful tribal clan led by the Houthi family. Since 2004, the Houthis have challenged the Yemeni central government, which has long been dominated by Sunnis, in sporadic waves of fighting.

For years, the Houthis were the most peripheral of Iran’s network of allies in the so-called “Axis of Resistance.” But growing turmoil in Yemen, after the 2011-12 Arab uprising ousted a president closely aligned with Saudi Arabia, increasingly made Yemen a regional flashpoint. It embodied tensions between predominantly Shiite Iran and Saudi Arabia, a Sunni monarchy and the guardian of Islam’s holy places. In 2014, the Houthis seized Sanaa, Yemen’s capital, and toppled the central government. In response, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates launched an intensive air war in 2015.

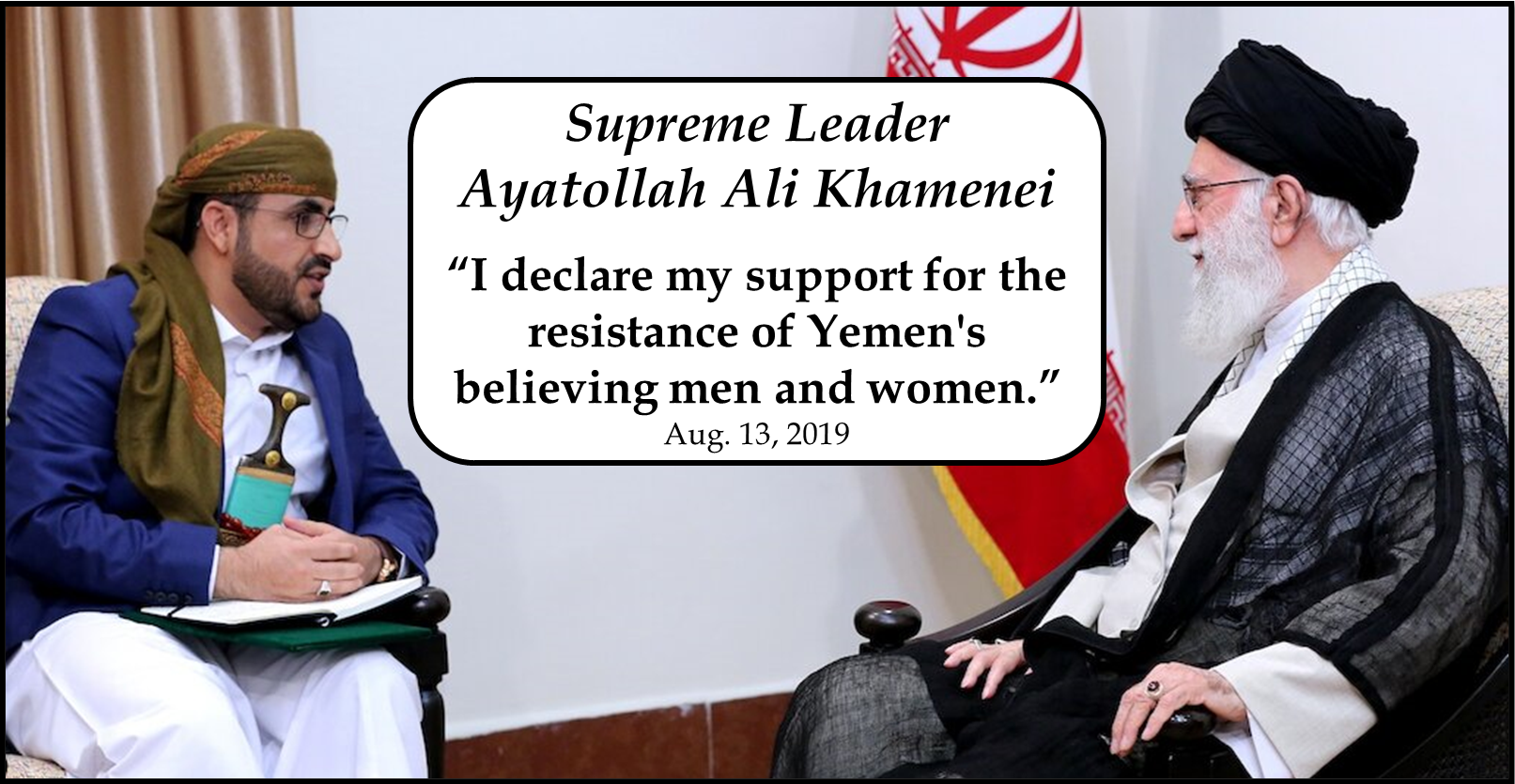

Tehran then started providing “a growing arsenal of sophisticated weapons and training” used to attack opponents as well as international shipping along its coasts on the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, according to the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency. Iran began sending ballistic and cruise missiles to the Houthis by 2015 and advanced drones by 2017.

The Houthis saw an opportunity to raise their international profile as soon as war broke out between Hamas and Israel in October 2023. First, they fired missiles and drones at Israel, more than 1,000 miles away from Yemen. Then they launched dozens of attacks on merchant and U.S. warships in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, effectively impeding commercial Red Sea shipping, which accounted for 15 percent of global seaborne trade. Houthi hostilities in the Red Sea soon constituted one of the most significant global reverberations emanating from the Gaza conflict. The Houthis posed the biggest international threat from Iran’s network of allies.

The Biden administration responded by mobilizing two coalitions. The first, Operation Prosperity Guardian, with more than 20 partners, was created in mid-December 2023 to defensively protect international shipping by intercepting Houthi drones and missiles. Shortly after, in January 2024, Operation Poseidon Archer, which was launched by six nations, preemptively attacked Houthi military assets.

In the first eight months of the conflict, U.S.-led forces conducted more than 450 strikes on Houthi targets and intercepted more than 200 drones and missiles. The U.S. Navy had not operated at such a pace since World War II.

The movement welcomed the fight and was not noticeably deterred by the attacks. “We praise God for this great blessing and great honor for us to be in a direct confrontation with Israel and America,” leader Abdel Malek al Houthi declared in early 2024.

What is the relationship between the Houthis and Iran? And what do the Houthis want from Iran?

Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has armed, trained and funded militias and political movements across the Middle East. In some cases, it played a key role in establishing allies, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and a plethora of Shiite militias in Iraq. In other instances, Iran sponsored existing groups with overlapping goals, including Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad in the Palestinian territories. The Houthis fit that template.

The Houthis had at least three reasons for looking to Iran. First, Iran had a proven track record for supporting regional allies. Iran could provide missiles and drones that the Houthis otherwise could not procure. Second, they shared the same anti-American and anti-Israeli worldview. Both wanted to limit the influence of Saudi Arabia, Iran’s regional rival. Third, Iran was the only Shiite power in the region. Although the Houthis and Iranian Shiites practiced different types of Shiism, Houthi leaders and clerics did travel to Iran for religious study and were inspired by the 1979 Islamic revolution.

The Houthis were an independent movement with its own constituency and domestic interests. In 2014, Iran reportedly advised the Houthis against taking over Sanaa, but they pressed on. They have repeatedly rejected the notion that they are beholden to Tehran. “We do not take orders from Iran; I must emphasize that the Yemeni people have dignity,” spokesperson Mohammad Abdulsalam said in December 2023.

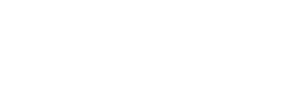

Iran and the Houthis developed more of a partnership than a top-down or patron-proxy relationship, according to Professor Thomas Juneau at the University of Ottawa. “The Houthis are fiercely nationalist, and do not take orders from Iran,” he told The Iran Primer. “Instead, they work together, closely, on the basis of their common interests.”

Michael Knights, a senior fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, described the relationship as an alliance and a meeting of minds. “The Houthis,” he said, “would do the same thing the Iranians told them to without being told, in a lot of cases.”

Houthi leaders modeled their movement after Hezbollah, a Lebanese political movement and one of the world’s most heavily armed non-state actors. They looked to Hezbollah as an “older sibling” and to Iran as a “sort of parent,” according to Knights. These relations were reflected in the composition of the Houthi’s decision-making body for military and security issues, the Jihad Council, again modeled after Hezbollah. For years, an Iranian advisor, a Qods Force brigadier general, has served as the “Jihad Assistant,” with a Hezbollah deputy in the inner circle of the council.

But Iran has downplayed its relationship with the Houthis, seeking to assert some level of plausible deniability. The movement “has its own tools,” then-Deputy Foreign Minister Ali Bagheri said in December 2023, “and acts in accordance with its own decisions and capabilities.” Tehran has long denied Western and Saudi allegations that Iran has provided advanced weapons, training and intelligence. Iran tries to “pretend it has a bit of a hands-off posture when it comes to its proxies around the region, but that is not the way that we view it,” John Kirby of the U.S. National Security Council said in a January 2024 press call about Houthi maritime attacks.

The Houthis have been self-sufficient in some respects. Although they acquired their most advanced weapons from Tehran, they also accumulated a vast arsenal from Yemeni army stockpiles, the black market, and through tribal alliances.

The Houthis “enjoy relative economic independence and do not completely rely on Iranian aid,” the U.N. Panel of Experts on Yemen reported in late 2023. The panel cited analysts who questioned Iran’s ability to influence Houthi decisions. The Houthis generated revenue several ways without Iranian assistance, including:

- collecting customs revenue from the Hodeidah and Salif ports

- appropriating assets of political opponents or people who fled Yemen

- collecting zakat (almsgiving) and khums (a one-fifth tithe)

- operating in the black market

- smuggling drugs

- extorting vulnerable people and institutions

- confiscating Yemeni state resources.

Calculating the exact monetary value of Iran’s assistance to the Houthis was difficult. But experts generally agreed that Tehran’s investment has been relatively limited. The combined value of Iran’s annual support may amount to $100 to $300 million, according to Juneau. “This would therefore be significantly smaller than Iran’s support for Hezbollah, which is often estimated in the upper hundreds of million per year, or perhaps $1 billion.”

What does Iran want from the Houthis?

For decades, Iran has pursued a multipronged strategy to engage threats far from its borders. Its militia allies in the Axis of the Resistance, including the Houthis, have played a major role in this “forward defense” doctrine. The Houthis have been particularly useful for field testing Iran-made weapons, including missiles, as well as tactics against U.S. forces and regional adversaries, including Saudi Arabia.

The Houthis have boosted Iran’s strategic position in the region, largely due to geography. They have helped pressure Saudi Arabia, a common adversary. Iran, from the northeast, and the Houthis, from the south, have been able to flank the kingdom and divide its attention.

The Houthis, in theory, could be even more useful than some of Iran’s other allies, Knights told The Iran Primer. From Lebanon, Hezbollah has long provided Iran with “specialized, close-range deterrence against Israel,” he said. But Yemen could be a springboard for broader operations.

For thousands of years, Yemen has been an important hub for trade between Africa, the Middle East and Asia. The Bab al Mandab Strait, just 20 miles wide and 70 miles long, was a chokepoint linking the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean. Houthi attacks across several strategic waterways have projected Iran’s power far beyond its borders. Since at least 2019, the Houthis have launched attacks on commercial shipping in the:

- Red Sea and Bab al Mandab Strait

- Gulf of Aden

- Gulf of Oman

- Arabian Sea

- Persian Gulf

Iranian leaders lauded the Houthis for disrupting shipping through the Red Sea starting in late 2023. “Yesterday, the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz became a nightmare for them [Western powers], and today they are trapped ... in the Red Sea,” Brigadier General Mohammad Reza Naqdi, the coordinating commander of the Revolutionary Guards, said in December 2023. “They shall soon await the closure of the Mediterranean Sea, (the Strait of) Gibraltar and other waterways.”

But Farzin Nadimi, a senior fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, said that the threats against the eastern Mediterranean shipping were “empty.” He doubted that Houthi drones, such as the Samad-4, could maintain a stable data link and reliably hit a moving target 1,200 miles or further away from Yemen.

What military aid has Iran provided to the Houthis?

For years, Iran has provided weapons, training and military advisors to the Houthis. Tehran has smuggled an increasingly advanced and lethal arsenal to the Houthis via the Arabian Sea and Gulf of Aden, via the Horn of Africa, and over land through Oman. From 2013 through March 2024, the United States and its partners interdicted at least 18 ships carrying weapons to the Houthis.

Iran initially transferred small arms – including assault rifles, sniper rifles and rocket-propelled grenades. Later, Iran’s Qods Force, the external operations arm of the Revolutionary Guards, provided ballistic and cruise missiles as well as attack drones, including models that could hit targets more than 1,000 miles away.

Tehran’s support, including arms transfers, to the Houthis dates back to at least 2009, when Riyadh was drawn into the conflict between the Houthis and Yemen’s pro-Saudi central government. After border clashes between the Houthis and Saudi forces, the Saudis launched air strikes against the rebels. More than 130 Saudis died in the fighting. For Iran, supporting the Houthis became a convenient way to weaken regional rival Saudi Arabia and its allies in Yemen.

Between 2012 and 2020, Iran spent “hundreds of millions of dollars” aiding the Houthis, according to the State Department. Evidence mounted. In January 2013, the U.S. Navy, in cooperation with the Yemeni Navy, seized a ship carrying Katyusha rockets, anti-aircraft missiles, explosives, radar systems, and ammunition. The Iranian-made weapons were allegedly bound for the Houthis. And the Yemeni crew members said that they sailed from Yemen to Iran and back without passing through immigration or customs in either country.

Since at least 2014, Iran and its ally, Hezbollah, have deployed operatives to train, equip and advise the Houthis. Iran has also helped the Houthis set up workshops to produce or assemble weapons. Iran’s provision of advanced weapons to the Houthis coincided with the next major round of Saudi-Houthi fighting. In March 2015, a coalition led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) launched an air campaign against Houthi targets in Yemen. As the war dragged on, despite U.N. efforts to broker peace talks, the Houthis deployed increasingly sophisticated weapons.

Since at least 2015, Iran has provided short- and medium-range ballistic and cruise missiles that have allowed the Houthis to hit land and sea targets from great distances. In 2017, the Houthis launched four ballistic missiles at targets in and around Saudi Arabia’s capital, Riyadh, some 600 miles from northern Yemen.

Both Iran and Hezbollah have denied U.S. and Saudi allegations of their deep involvement with the Houthis. “Iran’s assistance is at the level of advisory and spiritual support,” Revolutionary Guards commander Maj. Gen. Ali Jafari claimed in November 2017. Tehran has rarely hinted at providing weapons. But in May 2024, Tasnim News Agency, linked to the Revolutionary Guards, reported that technology for producing Iranian anti-ship missiles was “now at the disposal” of the Houthis.

What role has Iran played in the Houthi’s targeting of Israel and commercial shipping since October 2023?

In solidarity with Hamas and the Palestinians, the Houthis launched sporadic missile and drone attacks on Israel starting on Oct. 19, 2023. They proceeded to launch attacks–using drones, missiles, and small boats–on commercial shipping and naval warships in the Red Sea, one of the world’s most important waterways for international commerce. The Houthis initially claimed that they were targeting commercial ships on their way to or linked to Israel. The U.S. military alleged that Iran was providing targeting information to the militants.

Many shipping firms opted to take the long route around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope rather than the quicker route through the Suez Canal. By early 2024, 70 to 80 percent of container traffic had been rerouted due to the security risk.

By disrupting global shipping and attacking Israel, the Houthis proved themselves to be more useful than the Iranians thought, according to Knights. Tehran subsequently doubled down on its role of advice and assistance, especially in providing intelligence on potential targets, he added. Iran also may have accelerated resupply of weapons capable of striking ships and hitting Israel.

In late 2023, the Houthis started launching anti-ship ballistic missiles – provided by Iran – at ships in the Red Sea. “No one has ever used an anti-ship ballistic missile, certainly against commercial shipping, much less against U.S. Navy ships,” Vice Adm. Brad Cooper, deputy commander of U.S. Central Command, told CBS in February 2024.

Iran also provided intelligence to help the Houthis target merchant ships. “We know that Iran was deeply involved in planning the operations against commercial vessels in the Red Sea,” White House national security spokesperson Adrienne Watson said in December 2023. “This is consistent with Iran's long-term material support and encouragement of the Houthis’ destabilizing actions in the region.”

In March 2024, the Houthis fired a cruise missile that traveled nearly 1,000 miles before landing outside Eilat, Israel’s port on the Red Sea. It was the first time a Houthi weapon made it past Israeli and allied defenses and hit Israeli territory.

What other kinds of support has Iran provided to the Houthis?

In 2019, the U.N. Panel of Experts on Yemen reported that Iran was illicitly shipping fuel to Yemen and that the sales revenue was used to finance the Houthi war effort. Iran has also facilitated smuggling operations to help the Houthis financially. In 2021, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned Sa’id al Jamal, an Iran-based Houthi financier. His international network generated tens of millions of dollars in revenue for the Houthis and the Qods Force from selling Iranian commodities, including oil. “This network’s financial support enables the Houthis’ deplorable attacks threatening civilian and critical infrastructure in Yemen and Saudi Arabia,” said Andrea Gacki, director of the Office of Foreign Assets Control.

Officials from Yemen’s internationally recognized government have accused the Houthis of selling Iranian products at exorbitant prices to increase their profits. “The smuggling of Iranian crude and gas to the Houthi militia through the port of Hodeidah confirms that the Tehran regime continues to support and finance the militia,” Information Minister Muammar al Eryani said in June 2023.