Shaul Bakhash

One year after President Hassan Rouhani’s election, what are his administration’s main accomplishments?

After the eight disastrous years of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s administration, Rouhani’s signal achievement is simply to put government back into the hands of adults, of men and women of experience and common sense. Ahmadinejad managed to squander over $600 billion in oil revenues, to provide grounds for increasingly damaging sanctions against Iran, to exacerbate relations with almost all Persian Gulf countries and much of the international community, and to facilitate the penetration of the Revolutionary Guards into all major sectors of the Iranian economy achievement.

After the eight disastrous years of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s administration, Rouhani’s signal achievement is simply to put government back into the hands of adults, of men and women of experience and common sense. Ahmadinejad managed to squander over $600 billion in oil revenues, to provide grounds for increasingly damaging sanctions against Iran, to exacerbate relations with almost all Persian Gulf countries and much of the international community, and to facilitate the penetration of the Revolutionary Guards into all major sectors of the Iranian economy achievement. Rouhani must deal with this crippling legacy. His government represents a return to sensible policies both at home and abroad. Already the effects are discernible. Serious negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program are under way. The Persian Gulf states are re-engaging with Iran as evidenced by the Emir of Kuwait’s recent trip to Iran and the invitation extended to foreign minister Javad Zarif to visit Saudi Arabia. The United States and the EU feel, at the very least, that they have an interlocutor in Tehran with whom they can have a serious dialogue.

At home, unlike the Ahmadinejad administration, the Rouhani team understands that sanctions are doing serious damage to Iran’s economy. Iran’s banking system is threatened by non-performing loans and other weaknesses. The current level of government spending and budget deficits simply cannot be sustained. The role of the state and the Revolutionary Guards in the economy needs to be curbed. And restrictions on basic freedoms need to be eased.

Rouhani and his team have not begun to address, let alone resolve, these festering problems. But after eight years of denial by both the former president and the current supreme leader, a government is in office that comprehends the depth of the problems the country faces.

During his campaign, Rouhani pledged to create a government of “prudence and hope.” What is his strategy?

During his campaign, Rouhani pledged to create a government of “prudence and hope.” What is his strategy?

Rouhani’s top priority is to resolve the nuclear issue and get sanctions lifted. He and his foreign minister seem to believe that a breakthrough on the nuclear front and the end to sanctions will open the door to much else. With the nuclear issue and sanctions out of the way, Iran’s economy can begin to recover and produce much-needed jobs for university graduates and workers.

Rouhani’s top priority is to resolve the nuclear issue and get sanctions lifted. He and his foreign minister seem to believe that a breakthrough on the nuclear front and the end to sanctions will open the door to much else. With the nuclear issue and sanctions out of the way, Iran’s economy can begin to recover and produce much-needed jobs for university graduates and workers. Major foreign investors can be drawn into Iran’s oil and other industries. Iran can begin to reintegrate into the international community and secure a place at the table in the discussion with the US and others on major regional issues. A political opening at home will be more feasible under more prosperous economic conditions. Such, at least, seems to be the game plan.

On what issues has Rouhani fallen short?

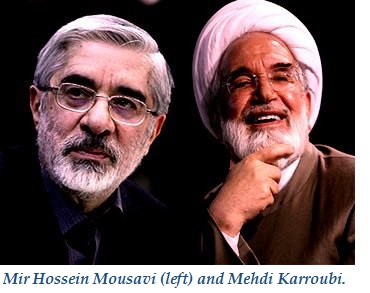

The record of the Rouhani government in the first year is clearly a mixed bag. On the home front, there is an easing of social and press restrictions—everyone agrees the environment is decidedly freer—but arrests of bloggers, dissidents and critics continue. Publications are closed down. Sporadic crackdowns on women and the young occur. Some political prisoners have been released, including the human rights lawyer, Nasrin Sotoudeh, but many remain in prison—most notably the two Green Movement leaders, Mehdi Karroubi and Mir Hossein Mousavi.

The record of the Rouhani government in the first year is clearly a mixed bag. On the home front, there is an easing of social and press restrictions—everyone agrees the environment is decidedly freer—but arrests of bloggers, dissidents and critics continue. Publications are closed down. Sporadic crackdowns on women and the young occur. Some political prisoners have been released, including the human rights lawyer, Nasrin Sotoudeh, but many remain in prison—most notably the two Green Movement leaders, Mehdi Karroubi and Mir Hossein Mousavi. Rouhani clearly controls neither the security services nor the judiciary, which seem determined to flout his desire to open up the political system. For example, political prisoners at Evin Prison were attacked and beaten by guards in April, when they persisted in peaceful protests. Mostafa Tajzadeh, the outspoken member of the former Khatami government was nearing the end of this six-year prison term when the judiciary slapped on another one-year prison term for supposed anti-state activities.

Rouhani’s appeal to Iranians to voluntarily give up the monthly government cash subsidy for all Iranians, which was instituted under Ahmadinejad, fell on death ears. Rouhani has talked about the need to reduce the Guards role in the economy, but he has done little on that score.

What obstacles does Rouhani face on his domestic policy?

An entrenched and narrow ruling elite, often described as hardliners or conservatives, control the principle instruments of power: the security agencies, the intelligence ministry, the military and the police, the judiciary, the Council of Guardians (which has the power to veto laws and candidates for elected office), and the Assembly of Experts, which will choose the next Supreme Leader. Connected to them is an economic elite, which has grown enormously wealthy on government contracts and quasi-monopolies of major import goods.

These elites will resist any challenge to their hold on power and privilege. They also fear, perhaps with good reason, that any serious reform, whether political, economic or social, will open the floodgates and trigger a process of change that will end up threatening the whole system.

The resistance has an ideological dimension as well. Like the Maoists in China or the Brezhnevites in the Soviet Union, Iran’s political and economic elites attack proposals for change as abandonment of revolutionary principles and disloyalty to revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini. Such accusations are often self-serving—an easy way to besmirch the reputation of a rival—but they do reflect the rigidity and resistance to change that characterizes many in the conservative camp.

The resistance has an ideological dimension as well. Like the Maoists in China or the Brezhnevites in the Soviet Union, Iran’s political and economic elites attack proposals for change as abandonment of revolutionary principles and disloyalty to revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini. Such accusations are often self-serving—an easy way to besmirch the reputation of a rival—but they do reflect the rigidity and resistance to change that characterizes many in the conservative camp. In early June, Ayatollah Mohammad Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi, the powerful and arch-conservative religious leader, challenged Rouhani’s more liberal interpretation of Islam. He asked, mockingly, if the president had learned his Islam in England rather than at a seminary in Qum. He also seemed to sneer at Rouhani’s focus on getting sanctions lifted, “and not by resistance but through diplomacy, contrary to the line of the Imam [Khomeini].”

What obstacles does he face on foreign policy?

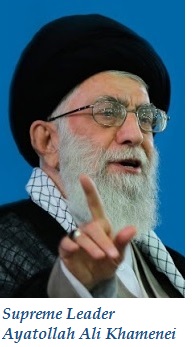

The opposition Rouhani faces at home to his foreign policy agenda stem from similar sources. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei wears his unyielding opposition to the United States and its hegemonic role in the world as a badge of honor. He said recently that this “war” between the Islamic Republic and “world arrogance” has no limit; it will be unending.

The opposition Rouhani faces at home to his foreign policy agenda stem from similar sources. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei wears his unyielding opposition to the United States and its hegemonic role in the world as a badge of honor. He said recently that this “war” between the Islamic Republic and “world arrogance” has no limit; it will be unending. Critics on the right charge that Rouhani has already surrendered too much for too little in the nuclear negotiations. Hossein Shariatmadari, editor of the hard line Kayhan newspaper, wrote that the reported breakdown during the previous round of nuclear negotiations was a cause for celebration.

On the nuclear issue, Khamenei has clearly allowed criticism to continue, but he has also not allowed such criticism to sabotage the negotiations. Iran will have to make extremely difficult concessions, but the need to get sanctions lifted could result in an agreement. Beyond the nuclear issue, however, Rouhani may have a hard time addressing other foreign policies that exacerbate Iran’s relations with the United States and European Union—even if he were so inclined.

Some critical foreign policy issues also remain the domain of the Supreme Leader and his cohorts in the security agencies and the Revolutionary Guards. Iran’s support for Hamas and Lebanon’s Hizballah, both strong opponents of Israel, are unlikely to end. Tehran’s official position--that Israel is an illegitimate state that should not exist—is also unlikely to change. Iran’s alliance with President Bashar Assad in Syria is also firm.

As it strives for improved relations with the West, Rouhani’s team may hope that it can move on some issues but isolate others. It seeks common ground with the West and even its Persian Gulf neighbors in trade and investment, on resistance to violent Islamic Salafists, and security arrangements for the Persian Gulf even while agreeing to disagree on Israel, the Palestinians, Syria and other issues. Those all await the future.

Shaul Bakhash is the Clarence Robinson Professor of History at George Mason University.

Photo credits: President.ir, Mir Hossein Mousavi Facebook page, Assembly of Experts website, Khamenei.ir

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org