Kelsey Davenport is the Director for Nonproliferation Policy at the Arms Control Association.

Is restoring the nuclear deal with Iran—brokered in 2015 and abandoned by the United States in 2018—still possible after almost two years of stalled diplomacy?

From a technical perspective, restoring the agreement, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), is possible. Politically, however, it will be challenging.

On the technical side, many of Iran’s violations of the nuclear deal were reversible as of early 2023. Iran could immediately halt uranium enrichment to levels above the JCPOA cap of 3.67 percent. It has enriched uranium to 60 percent – close to 90 percent, which is considered weapons-grade. Iran could blend down its enriched uranium to natural levels or ship out the excess stockpiles to another country. Additionally, it could store, dismantle or destroy centrifuges installed and operating in excess of JCPOA limits. Iran would need to halt enrichment at the Fordo facility, buried under the mountains near Qom. It would also need to remove any uranium and advanced IR-6 centrifuges from the site. Iran has, however, gained knowledge from enrichment to 60 percent and its operation of advanced centrifuges that cannot be reversed.

The U.N. nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), could reestablish the intrusive monitoring and verification provisions required by the deal. The agency would, however, face difficulties re-establishing the baseline knowledge of Iran’s program. It would need to bridge the gap in monitoring and access to certain sites that support the nuclear program but do not house nuclear materials, such as enriched uranium. Inspectors have not had access to these sites since February 2021. In June 2022, Iran disconnected the cameras intended to provide the IAEA with recordings of activities at these locations if the JCPOA was restored. Without an accurate baseline, verifying certain JCPOA limits could be challenging for the IAEA.

The primary challenge was on the political side as of early 2023. The world’s six major powers – Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States – were very close to reaching an agreement with Iran in August 2022. But the talks stalled after Iranian negotiators made unrealistic demands beyond the scope of the JCPOA. They stipulated that Iran would agree to a deal only if the U.N. nuclear watchdog closed an investigation into traces of uranium found at three undeclared sites within a specified period. They also demanded that the IAEA never again investigate Iran’s past nuclear activities.

But the United States and its partners cannot dictate how the IAEA applies safeguards. Pressuring the U.N. agency could undermine its credibility and independence, which are crucial for its sensitive work monitoring and verifying the peaceful nature of nuclear programs worldwide. Iran’s insistence on tying this extraneous issue to the JCPOA raised questions about its intentions to return to the deal.

In the fall of 2022, the U.S. and European focus shifted to Iran’s brutal crackdown on domestic protests and its provision of drones to Russia for the war in Ukraine. Iran was prohibited from selling certain types of drones, missiles, and related technology under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231, which endorsed the JCPOA, until October 2023. The Biden administration felt pressure not to engage with Tehran while the protests continued, narrowing the political space for reviving the deal.

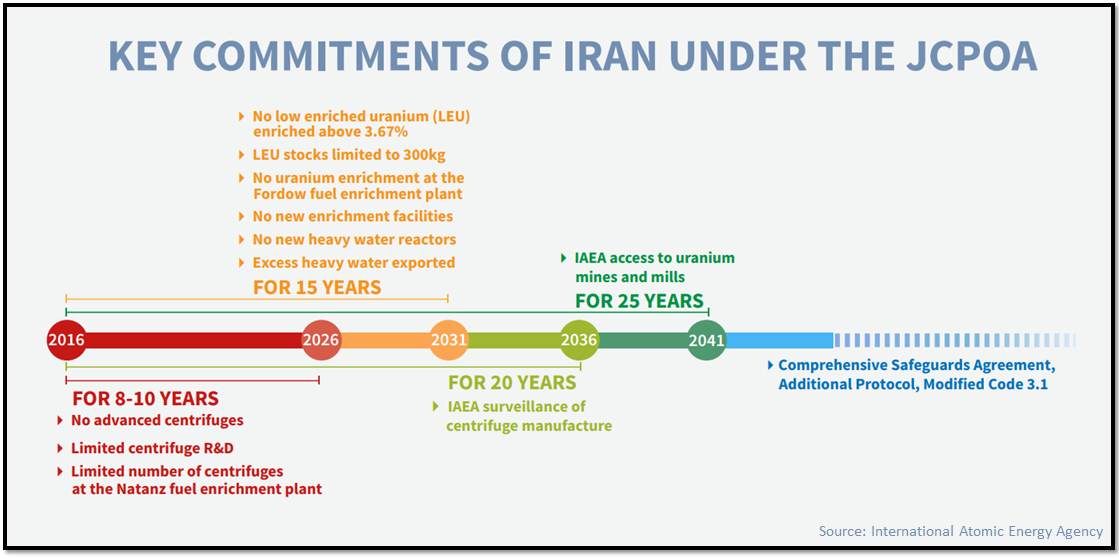

The JCPOA included expiration dates, or “sunset” clauses, for certain restrictions on Iran. Which sunset dates have already passed or are coming up? Are there any remaining nonproliferation benefits?

Restoration of the JCPOA’s limits and intrusive monitoring provisions would provide significant nonproliferation benefits. Iran’s breakout time – the time needed to produce enough fuel for one nuclear bomb – would increase from less than one week to somewhere in the four- to six-month range. That extended timeline would give the international community significantly more time to act if a breakout was detected.

Reinstating the monitoring mechanisms – the most intrusive ever negotiated – would provide significantly more insight into the nuclear program. This would provide greater assurance that a breakout would be detected more quickly and protect against Iran diverting materials for covert activities.

Some of the JCPOA’s most crucial nonproliferation benefits are permanent. Iran must implement the Additional Protocol, which expands IAEA access to facilities and information, in perpetuity. The more intrusive monitoring and verification requirements are long-term guardrails against a nuclear-armed Iran. The JCPOA also prohibits Iran from undertaking certain activities relevant to building the explosive package for a nuclear weapon in perpetuity.

Other provisions from the JCPOA and U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231 expire over time. In October 2020, the U.N. conventional arms embargo on Iran was lifted. It was the first set of restrictions to expire, five years after the JCPOA was adopted. More concerning are restrictions due to expire in October 2023. U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231 barred Iran from importing or exporting certain types of missiles and drones without Security Council approval. In 2022, Iran already provided Russia with hundreds of drones for use in the war on Ukraine. It may plan to transfer missiles as well, according to the White House. The United States and its European partners have alleged violations of Resolution 2231. But the October 2023 “sunset” provision will make the matter moot.

Some of the more significant limitations on Iran's uranium enrichment program will phase out in 2031, 15 years after the deal was implemented. They include the cap on the enriched uranium stockpile and the limits on enrichment to 3.67 percent. When these limits expire, Iran’s breakout time could shorten again, potentially down to zero. But absent the JCPOA, Iran was already at near-zero breakout in early 2023. From a nonproliferation perspective, the eight-year delay is preferable.

What are the alternatives to the JCPOA?

If the JCPOA cannot be resurrected, there is no good Plan B. Every alternative has drawbacks. The best option would be an interim deal or a set of voluntary reciprocal measures to stop the cycle of escalation and create time for further diplomacy. Iran’s nuclear advances have increased the risk of conflict and military strikes on its program.

In an interim deal, what minimal steps would Iran need to take to assure the international community that its nuclear program is peaceful?

In the short-term, the focus should be on increasing the monitoring and verification of Iran’s nuclear program. Greater access for IAEA inspectors, including the resumed monitoring of facilities no longer subject to inspection, would have crucial benefits that could de-escalate tensions.

First, transparency would provide greater assurance that any breakout would be detected more quickly. Second, it would help ensure that any nuclear materials or components, like centrifuges, were not being diverted for a covert program. Increasing monitoring reduces the proliferation risk.

If Iran wants to demonstrate that its nuclear program is peaceful, it should be willing to take these steps. More intrusive monitoring would support Tehran’s claims that it has no intention of pursuing nuclear weapons.

In a new deal, what steps would the United States have to take to incentivize Iran to halt or freeze its advances?

The United States would probably have to consider limited – and easily reversible – sanctions relief. Iran would need to quickly reap economic benefits commensurate to its concessions. The United States could, for example, unfreeze assets held abroad, or provide waivers for limited oil sales.

What would be the most effective ways to prolong the breakout time – the time that Iran would need to produce sufficient fissile material for one nuclear weapon?

The most effective ways would be to cap or eliminate the stockpiles of highly enriched uranium. Iran is unlikely to give up its stockpiles of 20 percent and 60 percent enriched uranium, which it sees as key sources of leverage. The proliferation risk could be mitigated, however, by capping how much uranium Iran keeps in gas form or converting uranium gas to powder. (Powder can be reconverted to gas, but that is a time-consuming and easily detected process.) Another option would be to limit the number of advanced centrifuges installed or operated.

What are the limitations of military or kinetic options?

In the short run, sabotage or military strikes could extend Iran’s breakout time. But Tehran has historically responded to sabotage, including the assassination of nuclear scientists, by accelerating its nuclear activities and hardening its facilities. In any case, disrupting activities at the key Fordo facility would be difficult because it is built deep under the mountains near Qom and difficult to destroy using conventional military explosives.

Iran has long had the requisite knowledge to build a nuclear weapon. In 2007, the U.S. intelligence community already assessed that Iran had the technical capabilities to build a bomb if it made the political decision to do so. Since then, Iran has only further refined and advanced its nuclear program. It has gained extensive knowledge of the uranium enrichment process and the operation of advanced centrifuges. Such knowledge cannot be bombed away. There is also a risk that a strike could motivate Iran to build nuclear weapons to deter further military action.

What can be done to mitigate the danger of armed conflict involving Iran and either the United States or Israel?

Tehran risks miscalculating just how far it can accelerate its nuclear program without inadvertently triggering a U.S. or Israeli military response. Neither the United States nor Israel has set clear red lines regarding Iran’s nuclear advances. And their responses to significant escalations, like enriching uranium to 60 percent (a technical step away from weapons-grade or 90 percent purity) were relatively muted. The United States and Israel could convey privately to Tehran what actions might trigger a military response.

Increasing transparency over Iran's nuclear program could also mitigate the danger of conflict. The United States and Israel would be less likely to misjudge Iran’s intentions if any move toward producing nuclear weapons could be easily detected and they had greater assurance that Iran was not diverting materials for a covert nuclear program.