Nima Gerami

Iran’s political elite has become increasingly divided over the course of nuclear negotiations with the world’s six major powers, which began last fall. The current debate appears to fall into three camps:

• Nuclear supporters. This faction reportedly includes Revolutionary Guards officials, personnel from the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), and members of the conservative Steadfast Front and its spiritual leader Ayatollah Mohammad Taghi Mesbah-Yazdi. They criticize suspension and temporary constraints on nuclear capabilities. They also reject prospects that the outside world will dictate Iran’s security needs.

“The most advanced weapons must be produced inside our country even if our enemies don’t like it. There is no reason that [our enemies] have the right to produce a special type of weapon, while other countries are deprived of it,” Mesbah-Yazdi said in 2005.

But nuclear supporters span the political spectrum and also include noted reformists who maintain that Iran does not need to bow to Western demands over its nuclear program. They also oppose full domestic transparency or accountability on the nuclear issue.

• Nuclear centrists. Led by President Hassan Rouhani and former President Hashemi Rafsanjani, nuclear centrists argue that Tehran should be flexible in its interaction with the West. They appeal to mantiq (or rationality). They also believe that isolationist policies will ultimately weaken Iran’s economic and political standing in the world.

“It is good to have centrifuges running, provided people’s lives and livelihoods are also running,” Rouhani said in 2013.

“It is good to have centrifuges running, provided people’s lives and livelihoods are also running,” Rouhani said in 2013. The centrists appear more willing to accept constraints on the nuclear program to end Iran’s international isolation, improve the economy, and preserve regime stability. They also appear more flexible on issues such as capping uranium enrichment levels and modifying the Arak heavy water reactor to reduce the amount of plutonium produced.

• Nuclear detractors. Comprised mostly of former government officials and academics affiliated with the banned reformist Islamic Iran Participation Front, nuclear detractors question the practical need for a civil nuclear energy program, given the cost of sanctions and other national priorities.

“Contrary to its claims, the regime is secretly preparing to produce weapons of mass destruction…This whole issue has turned into a point of weakness for the country, and the foreign powers are using it to exert pressure on us. In other words, instead of generating power and strength for Iran, the nuclear issue has only weakened it,” said Dr. Ahmad Shirzad, former parliamentarian and professor of physics at the Isfahan University of Technology in 2003.

After his election in 2005, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad began to purge reformists from government. But the detractors continued to challenge the need for a nuclear program. Former Interior Minister Abdollah Nouri called for a national referendum on the issue in 2012. And Nouri’s former deputy, Mostafa Tajzadeh, a prominent reformist arrested after the disputed 2009 presidential election, continues to publish open letters from Evin Prison criticizing Tehran’s nuclear policies.

After his election in 2005, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad began to purge reformists from government. But the detractors continued to challenge the need for a nuclear program. Former Interior Minister Abdollah Nouri called for a national referendum on the issue in 2012. And Nouri’s former deputy, Mostafa Tajzadeh, a prominent reformist arrested after the disputed 2009 presidential election, continues to publish open letters from Evin Prison criticizing Tehran’s nuclear policies. President Rouhani has taken several steps to sideline his domestic critics. He reshuffled the AEOI leadership and moved several officials who had opposed nuclear negotiations, according to an AEOI spokesman. In September 2013, Rouhani also transferred the nuclear file from the Supreme National Security Council to the foreign ministry. The switch made Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif the chief nuclear negotiator and improved the atmospherics of nuclear talks. Rouhani has also tried to persuade the Supreme Leader to curb the economic and political influence of the Revolutionary Guards, whose leaders have been consistent critics of Rouhani’s engagement with the West.

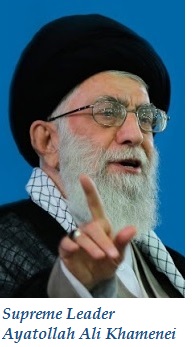

The Supreme Leader has the final say on the nuclear issue and, so far, he has been both supportive and skeptical about negotiations— creating distance and deniability if diplomacy fails. He has set red lines for Rouhani’s negotiating team, warning that any comprehensive agreement should not forfeit Iran’s nuclear research and development activities, including its “right” to enrich uranium and its ballistic missile program.

The Supreme Leader has the final say on the nuclear issue and, so far, he has been both supportive and skeptical about negotiations— creating distance and deniability if diplomacy fails. He has set red lines for Rouhani’s negotiating team, warning that any comprehensive agreement should not forfeit Iran’s nuclear research and development activities, including its “right” to enrich uranium and its ballistic missile program. Rouhani has bet heavily on resolving Iran’s economic crisis through nuclear negotiations. But sanctions relief and Rouhani’s economic policies have produced only marginal improvements in reducing and stabilizing inflation. Meanwhile, the administration’s subsidy reforms have led to a surge in gasoline prices, stoking fears of unrest. And the clock is ticking on diplomacy. The same domestic critics of nuclear talks, particularly within the Steadfast Front, have sought to sow discord by stepping up criticism of Rouhani’s social and cultural policies. Public discontent could carry high political costs for Rouhani and potentially even convince the Supreme Leader to further distance himself from any nuclear deal.

Despite being portrayed as a core national interest, Tehran’s nuclear policies are subject to little rigorous, well-informed public debate. Since 2004, the Supreme National Security Council, Iran’s highest formal decision-making body, has issued censorship rules limiting official comments on the nuclear program. Many aspects of the nuclear program remain shrouded in secrecy. Members of Parliament have complained that Iran’s nuclear facilities have been funded outside normal budgetary channels, with little to no parliamentary oversight on either sites or diplomacy.

In his 2011 memoir, Rouhani describes differences among the political elite, particularly on engagement with the West, which frustrated nuclear talks with the European Union between 2003 and 2005. Internal divisions made decision-making difficult and prevented Iran from negotiating from a position of strength, according to Rouhani. His memoir provoked criticism from political opponents, including former nuclear negotiator and presidential candidate Saeed Jalili. Jalili’s campaign manager accused Rouhani of disclosing classified information in his controversial memoir.

Elite divisions could again undermine Iran’s diplomacy if the Supreme Leader concludes that the political costs of alienating the regime’s power base—including the Revolutionary Guards, intelligence services, and the paramilitary Basij—outweigh the economic benefits of a comprehensive agreement with the West. Whether the Supreme Leader consents to a Rouhani-brokered deal will be heavily influenced by the views and attitudes of Iran’s political elite.

Nima Gerami is a research fellow in the Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction at the National Defense University. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the US government.

Photo credits:Ali Jafari via Leader.ir, Hassan Rouhani via President.ir, Abdollah Nouri by Meysam Khezri via Qom_IRAN and Flickr, Ali Khamenei via Khamenei.ir

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org