The following article was originally published as Viewpoints No. 52 by the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Shaul Bakhash

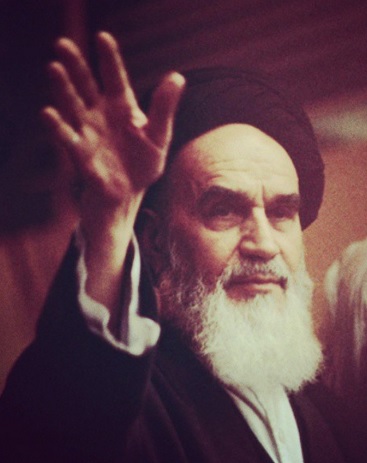

The Iranian revolution, resulting in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the Islamic Republic 35 years ago, underwent a long gestation. The first major protests began in January 1978 and continued for an entire year until the collapse of the monarchy in January 1979. The contrast with Egypt during the Arab Spring is striking. A mere 18 days passed between the first large-scale Egyptian protests and the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak. Iran witnessed an entire year of almost uninterrupted protests and demonstrations, strikes, pamphleteering, and sermonizing. Moreover, in Iran the protests were not confined to Tehran. They were a multi-urban phenomenon. By the late summer and early fall of 1978, almost all Iran’s major cities and dozens of smaller towns were in upheaval. This translated into an extraordinarily wide mobilization as more and more elements of the population and from all social strata were drawn into the opposition movement. This lengthy struggle also allowed the opposition, especially the men around Ayatollah Khomeini (left), to sharpen their message, to expand their networks, and to create—here I use the term with caution—the embryos of a parallel state. Moreover, this lengthy struggle radicalized and hardened the opposition, particularly the men around Khomeini. It inculcated in them habits of violence and a desire to inflict vengeance on those who had oppressed them. Once they seized power, these men were fierce in their determination to completely do away with the old order. To hold on to power they were willing to purge, imprison, and execute large numbers if necessary. They proved prime exemplars of Mao’s reminder that revolution is not a dinner party.

The Iranian revolution, resulting in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the Islamic Republic 35 years ago, underwent a long gestation. The first major protests began in January 1978 and continued for an entire year until the collapse of the monarchy in January 1979. The contrast with Egypt during the Arab Spring is striking. A mere 18 days passed between the first large-scale Egyptian protests and the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak. Iran witnessed an entire year of almost uninterrupted protests and demonstrations, strikes, pamphleteering, and sermonizing. Moreover, in Iran the protests were not confined to Tehran. They were a multi-urban phenomenon. By the late summer and early fall of 1978, almost all Iran’s major cities and dozens of smaller towns were in upheaval. This translated into an extraordinarily wide mobilization as more and more elements of the population and from all social strata were drawn into the opposition movement. This lengthy struggle also allowed the opposition, especially the men around Ayatollah Khomeini (left), to sharpen their message, to expand their networks, and to create—here I use the term with caution—the embryos of a parallel state. Moreover, this lengthy struggle radicalized and hardened the opposition, particularly the men around Khomeini. It inculcated in them habits of violence and a desire to inflict vengeance on those who had oppressed them. Once they seized power, these men were fierce in their determination to completely do away with the old order. To hold on to power they were willing to purge, imprison, and execute large numbers if necessary. They proved prime exemplars of Mao’s reminder that revolution is not a dinner party. Equally important, this continuous, day-after-day confrontation between the state and the people during the year of protests in 1978 gradually wore down the regime itself. Months of daily clashes between the protesters and the army led to widespread desertions among the ordinary rank and file. By the fall of 1978, except at the senior levels, the civil service itself had joined the ranks of the opposition. Much of the civil service went on strike. The mail was not being delivered; goods could not be released from customs; the garbage was not being collected; the banking system was paralyzed; industry was at a standstill; oil production was reduced to a trickle. In brief, the state administration had been brought down to its knees; and the very will of the ruling elites to retain power had been gravely eroded.

Equally important was the role of the army. In Egypt, army commanders fairly quickly withdrew any loyalty they believed they owed to Mubarak. In Iran, the officer corps remained loyal to the Shah to the very end. True, after the departure of the Shah (left) from Iran on January 16, 1979 and a couple of days before the final collapse of the old regime, the senior military commanders, in desperation as to how to deal with the continuing demonstrations, announced they would adopt a position of “neutrality” between the people and the regime—an announcement that led to the general uprising that brought the monarchy to an end. Still, in their hearts the senior commanders remained loyal to the king. So loyal that, according to a knowledgeable source, when the Shah was in exile in Morocco just after his departure from Iran, the senior military commanders telephoned him to secure his permission to stage a coup. The Shah refused to take their call.

Equally important was the role of the army. In Egypt, army commanders fairly quickly withdrew any loyalty they believed they owed to Mubarak. In Iran, the officer corps remained loyal to the Shah to the very end. True, after the departure of the Shah (left) from Iran on January 16, 1979 and a couple of days before the final collapse of the old regime, the senior military commanders, in desperation as to how to deal with the continuing demonstrations, announced they would adopt a position of “neutrality” between the people and the regime—an announcement that led to the general uprising that brought the monarchy to an end. Still, in their hearts the senior commanders remained loyal to the king. So loyal that, according to a knowledgeable source, when the Shah was in exile in Morocco just after his departure from Iran, the senior military commanders telephoned him to secure his permission to stage a coup. The Shah refused to take their call. In the eyes of the opposition, the army was deeply identified with the Shah. It was the army that had sought to suppress the anti-Shah protests and was held responsible for the deaths of demonstrators. Once the monarchy was overthrown, fear of a counter-revolution was pervasive. As a consequence, dozens of senior military commanders were executed. Very widespread purges of the officer class took place. Unlike the Arab Spring in Egypt, where the Egyptian army remained intact, ready to seize the opportunity offered by the anti-Muslim Brotherhood protests, to take power again, in Iran the army was denuded of its officer corps; it was disarmed and defanged. The revolutionaries succeeded in ensuring the army would be in no position to stage a counter-coup. Ironically, they also left Iran virtually defenseless, opening the door open for Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran in September 1980; but that is another story.

Khomeini’s leadership was also important, even crucial. The protests in Egypt and other countries of the Arab Spring produced leaders, of course. But Khomeini in Iran stands in a class by himself. I think one could argue that, the widespread protests in Iran notwithstanding, without Khomeini, there might have been change but there would not have been a revolution. He enjoyed enormous prestige because of his religious office, reputation for incorruptibility and long resistance to the Shah’s rule. He was a very powerful speaker; he had great charisma. His millions of devoted followers attributed to him legendary status, touched even by divinity. At the height of the revolutionary turmoil, it was put about and widely believed that his face had miraculously appeared on the moon. He remained steadfast in refusing any form of compromise and in his insistence that the Shah must go.

Khomeini also had a central idea—of Islamic government—that captured the imagination of a large swath of the Iranian protest movement. On examination, Khomeini’s treatise on Islamic government suggests only the vaguest notion of how such a government would be organized or how it would work. But the central notion of his treatise—that leadership in government belongs to the community of Islamic jurists as heirs to the mantle of the Prophet—became the basic pillar of the constitution of the Islamic Republic and remains so today. While much has changed in the composition of the ruling elites in Iran since the revolution, with men of secular backgrounds running the technical ministries and government departments, the commanding heights of power and the most sensitive positions in the state are still controlled by clerics—in alliance, of course, with the Revolutionary Guards. Indeed, if President Dwight Eisenhower were delivering a farewell address in Iran today, he would warn against the rise of a military-clerical complex.

It is true that a very broad coalition of forces made the Iranian Revolution. We like to believe that in Iran, as in the countries of the Arab Spring, a united people rose up in a demand for democracy and good government. But this should not obscure the fact that the Iranian Revolution was also a revolution of classes: of the underprivileged against the privileged; the poor against the rich and even the moderately well-off; those excluded from power against the ruling elites in the broadest sense; the upwardly mobile against those already part of the comfortable bourgeoisie.

Mehdi Bazargan, the first prime minister of the Islamic Republic, writes that when he was offered the position of prime minister, he described to the Revolutionary Council (RC) his criteria for choosing his cabinet. His cabinet officers, he told the members of the Revolutionary Council, would of course have to be men with a reputation for piety and oppositional activism, but they would also have to be men with the proper education, professional qualifications, and experience. Ayatollah Mohammad Hossein Beheshti, Khomeini’s principal representative on the RC, responded with a firm “no” to these criteria, Bazargan writes. Men of experience and education, Beheshti told Bazargan, (and I am paraphrasing) means “you people will hold office again. We have our people too. They may have no education or experience, but they also expect jobs and positions and they should get them. If necessary, we will assign them deputies with the proper qualifications.”

Like Bazargan, many of the middle-class professionals, members of the intelligentsia, university professors, economists, engineers, and mid-rank government officials did not understand that while they regarded themselves as revolutionaries and part of the opposition against the monarchy, the less privileged saw them as members of the privileged elite who had benefited from the old regime and who deserved to be driven out to make way for the newcomers. Ayatollah Beheshti also told an industrialist who came to see him after his factory had been expropriated: “For decades you people have enjoyed privilege, money and position. Now it is our turn.”

As a consequence, the revolution resulted in a sweeping transformation of elites. In the civil service, the top ranks, down to three or four levels, were eliminated through dismissal, purge, arrest, and flight. Like the army, the police forces were purged of their senior officers. The business elite—industrialists, contractors, bankers—were expropriated and a great deal of private wealth was taken over by the state. Similar transformations of elites took place virtually everywhere—in universities, in banks, in hospital administrations. Even in the clerical community, many of the highly respected members of the older clerical establishment were gradually marginalized to be replaced by middle-rank clerics identified with the Khomeini revolutionaries.

It is possible to argue that the electoral successes of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt during the Arab Spring also represented a reach for a share in power, privilege, and material reward by the underprivileged whom the Brotherhood represented. But in Egypt the old ruling elites remained in place; and the new claimants to power were soon ousted.

From its very beginnings, post-revolution politics in Iran has been characterized by deep divisions and fierce power struggles both among the wide range of groups that formed the original revolutionary coalition and among the men most closely identified with Khomeini himself. The radical students who seized the American Embassy in Tehran in November 1979 brought down the moderate Islamist government of Mehdi Bazargan. Iran’s first president, Abol-Hassan Bani-Sadr, who in his own disorganized way sought to tame the powerful currents and radicalism released by the revolution, was impeached by the clerical radicals in the second year of his presidency. After the ouster of Bani-Sadr, the men around Khomeini turned on the left-wing guerrilla organizations that had played a role in bringing down the Shah and in support of Khomeini. In the worst period of revolutionary terror witnessed since the revolution, thousands of members of these organizations were executed, sometimes in broad daylight on the streets of the capital. Arrests and repression gradually eliminated or neutralized members of the Tudeh (Iranian Communist) Party, elements of the old National Front, and other fringe groups.

By mid-1985, the men around Khomeini had eliminated most of the rival claimants to power. But this inner circle, it turned out, was not united; and while deep differences over policy and purpose remained muted due to the exigencies of the Iran-Iraq War, they emerged in force at the end of the war and with the death of Khomeini in 1989. Over the last two decades and more, conservatives of various stripes insisted on the enforcement of Islamic laws and principles, resisted any deviation from what they regarded as revolutionary ideals, and emphasized loyalty to the revolutionary organizations and the principle of concentration of power in the supreme leader’s hands. They competed for political primacy with the pragmatic domestic and foreign policies championed by President Ali-Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani (1989-1997), the sweeping and ultimately unsuccessful reformist policies of President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), and the populism of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013). These competing strands in the politics of the Iranian ruling elite reflected the unresolved political legacy—the unresolved political issues—generated by the 1979 revolution. Hassan Rouhani’s election as president in 2013 on a platform of moderate, cautious reform represents the latest attempt to address them.

Shaul Bakhash is the Clarence Robinson Professor of History at George Mason University.

This paper was presented at the Middle East Program meeting, “Iran’s Tumultuous Revolution: 35 Years Later” on February 10, 2014.