Interview with Moeed Yusuf

What is the status of relations between the Pakistan’s Sunni-dominated government and Iran’s Shiite theocracy under the new leaders, who both were elected in mid-2013? How do Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif get along? On what issues do they collaborate? On what issues are they divided?

Iran’s relationship with Pakistan is both cooperative and competitive. The neighbors coordinate on issues like trade and border security while often diverging on foreign policy. But Prime Minister Sharif and President Rouhani seem committed to improving bilateral relations.

In September 2013, the leaders met on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly in New York. “Pakistan and Iran enjoy [good] relations that are deeply rooted in historical, cultural and religious commonalities,” Sharif told Rouhani. Pakistanis generally have a positive view of their Western neighbor. A 2013 Pew poll found that 69 percent of Pakistanis had a favorable view of Iran, the highest percentage of 39 countries polled worldwide on perceptions of the Islamic Republic.

In September 2013, the leaders met on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly in New York. “Pakistan and Iran enjoy [good] relations that are deeply rooted in historical, cultural and religious commonalities,” Sharif told Rouhani. Pakistanis generally have a positive view of their Western neighbor. A 2013 Pew poll found that 69 percent of Pakistanis had a favorable view of Iran, the highest percentage of 39 countries polled worldwide on perceptions of the Islamic Republic. ECONOMY: During their meeting, Sharif told Rouhani that Pakistan especially wanted to improve economic ties. Both leaders emphasized their commitment to completing a multi-billion-dollar pipeline to deliver Iranian natural gas to Pakistan. The two countries, however, have long expressed grand aspirations for economic cooperation that have not materialized.

In 1964 Iran, Pakistan and Turkey established the Regional Cooperation for Development organization to promote trade, development and investment among the three countries. Its successor, the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), expanded membership in 1992 to include seven other neighboring states. In November 2013, Iran took over ECO’s rotating chairmanship at a ministerial meeting in Tehran.

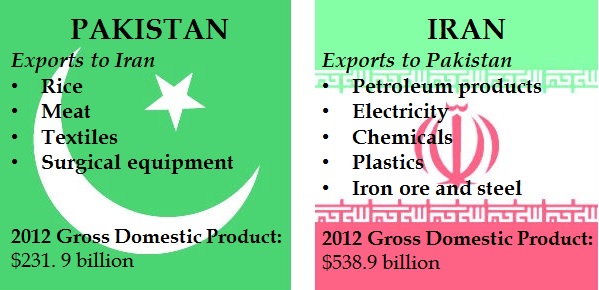

Pakistan has long viewed Iran, along with Afghanistan, as a potential gateway to trade with Western Asia. Yet Iran-Pakistan trade only amounts to some $1 billion annually. The two countries hope to boost trade to $5 billion by 2016.

REGIONAL ISSUES: But on many foreign affairs issues, Iran and Pakistan fall into opposing blocs. Pakistan is aligned with two of Iran’s chief adversaries, Saudi Arabia and the United States. Islamabad’s relationship with Washington is a particularly prickly issue for Tehran. But Pakistan wants to avoid getting caught in potential crossfire between and Tehran and Washington. Pakistan does not want another war on its border, so it opposes any military strike on Iran and tries to balance its relations with both countries. Pakistan’s Embassy in Washington actually hosts the Iranian interests section.

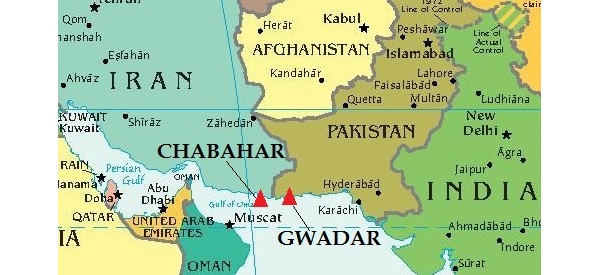

Pakistan is also particularly concerned about Iran’s relationship with India. New Delhi has reportedly invested $100 million in Iran’s southeastern port of Chabahar (below), which enables Indian exports to Iran and landlocked Afghanistan to bypass Pakistan. Chabahar is just 44 miles west of Pakistan’s Gwadar port and may help India expand trade ties into Central Asia. New Delhi has also reportedly invested in Afghan highways to Iran that would reduce Afghanistan’s dependence on Pakistan. India would also be less dependent on land routes through Pakistan to trade with Afghanistan.

RELIGIOUS ISSUES: A major sticking point between Pakistan and Iran is sectarian violence. Iran is particularly concerned about violence against Pakistan’s Shiite minority. Tehran alleges that Saudi promotion of hardline Wahhabi ideology among Pakistanis has inspired Sunni groups to attack Shiites. But many Pakistani experts consider Sunni-Shiite violence to be partly a product of a proxy war between Tehran and Riyadh.

Pakistan became the world’s first Muslim nuclear power in the early 1970s and later built first nuclear weapons in the Islamic world. What is Islamabad’s view of Iran’s controversial nuclear program?

Islamabad generally supports Iran’s right to a peaceful nuclear energy program. Most Pakistanis find fault with the West’s approach to the Iranian nuclear dispute.

But Islamabad would most likely oppose Tehran weaponizing its nuclear program. Pakistan’s regional clout would likely wane if another one of its four neighbors — in addition to China and India— attained nuclear weapons. Pakistan denies widespread suspicions that Saudi Arabia may be interested in receiving assistance in the nuclear field or with some form of defense against a future Iranian nuclear weapons capability. Islamabad does not want to get embroiled in a wider conflict and would thus want to avoid any development that could escalate the situation.

But Islamabad would most likely oppose Tehran weaponizing its nuclear program. Pakistan’s regional clout would likely wane if another one of its four neighbors — in addition to China and India— attained nuclear weapons. Pakistan denies widespread suspicions that Saudi Arabia may be interested in receiving assistance in the nuclear field or with some form of defense against a future Iranian nuclear weapons capability. Islamabad does not want to get embroiled in a wider conflict and would thus want to avoid any development that could escalate the situation. At the same time, Pakistan would almost certainly not condone an attack on Iranian nuclear facilities. A U.S. or Israeli strike could lead to increased turbulence on Pakistan’s southwestern border. In short, Islamabad is in an unenviable position. It is caught in the middle and does not want to upset Washington, Riyadh or Tehran.

Tehran and Islamabad have both tried to gain influence in war-torn Afghanistan since the 1970s. What issues have the two countries cooperated on? What has divided them?

Tehran and Islamabad have backed rival constituencies in Afghanistan. Iran has historically supported the Shiite Hazara minority to gain a foothold of influence. And it has invested in developing the western province of Herat (below). Afghanistan was a particularly contentious issue for Pakistan-Iran relations in the 1990s. Tehran opposed the Taliban, the Pakistan-backed group of extremists who took over the country in 1996. Shiite Iran nearly went to war against the Sunni Taliban after the massacre Afghan Shiites and several Iranian diplomats in Mazar-e-Sharif in 1998.

Tehran’s influence in Afghanistan cannot compare to Islamabad’s. Pakistan has deep ethnic and historical ties to Afghanistan going back thousands of years and a geographical advantage that is difficult to challenge. The Pashtun ethnic group, long dominant in Afghan politics, is also spread across Pakistan’s northern provinces and that bond runs deep at the people-to-people level even though state relations are not always cordial.

Tehran’s influence in Afghanistan cannot compare to Islamabad’s. Pakistan has deep ethnic and historical ties to Afghanistan going back thousands of years and a geographical advantage that is difficult to challenge. The Pashtun ethnic group, long dominant in Afghan politics, is also spread across Pakistan’s northern provinces and that bond runs deep at the people-to-people level even though state relations are not always cordial. Islamabad’s clout, however, has partially waned since the 2001 U.S. invasion. Both Tehran and India have stepped up efforts to back constituencies that have traditionally been on the opposite side of Pakistan’s preferred partners in Afghanistan.

At the same time, Pakistan and Iran have cooperated in the fight against drug smuggling from Afghanistan. Both countries are gateways for exporting opiates to Europe and other overseas markets. Domestic drug use also is fast becoming a serious problem in Pakistan and Iran.

Iran and Pakistan first discussed plans to jointly build a nearly 1,000-mile natural gas pipeline in 1994. Nearly two decades later, Iran is close to finishing the 560 mile portion on its side of the border. But Pakistan is lagging behind. What were the goals? How does it influence Iran-Pakistani relations, whether diplomatic, commercial or security? What are the current obstacles and constraints—and why?

Starting in the 1990s, Pakistan began searching for regional options to better meet its population’s energy demands. The pipeline offered an opportunity for Iran to more efficiently transfer natural gas to its eastern neighbor. Pakistan’s petroleum ministry projected annual savings of $2.4 billion on gas that could generate 4,000 megawatts of power. Completion of the pipeline might have improved commercial relations between the two countries. But divergent foreign policies probably would have kept the two from becoming close allies. The pipeline would have been more of an insurance policy to keep them from falling out.

The main obstacles to completion are U.S. and E.U. sanctions on Iran’s energy sector. Pakistan could incur stiff financial penalties for importing gas from Iran. Washington has tried to persuade Pakistan to investigate alternative ways to meets its energy demands.

Pakistan also faces numerous logistical obstacles to construction. It has struggled to finance construction of its part of the pipeline. In October, Islamabad even asked cash-strapped Iran for $2 billon to help builds its side of the pipeline. Actual construction of the pipeline may also prove difficult because the planned route crosses the restive Balochistan region.

Pakistan also has less of an incentive to complete the project since India dropped out of the project in 2009, reportedly due to U.S. pressure. Observers initially dubbed the project the “peace pipeline” in hopes that it would promote better India-Pakistan relations. Islamabad was particularly interested in valuable revenue from transit fees. That said, the formal agreement between Iran and Pakistan on the pipeline implies that Islamabad must build its part of the infrastructure or pay heavy damages to Iran. So if Pakistan has to get out, it has to find a creative way of calling off the deal. During the November ECO meeting, officials from both countries agreed to fast track talks on the pipeline and chart a more realistic time frame for construction.

Iran’s 500-mile border with Pakistan runs through the homeland of the Baloch —a Sunni ethnic group that has waged a decades-long insurgency against both countries. How have the two countries cooperated on this issue?

Both countries oppose Balochi aspirations for independence. Iran is particularly concerned that the Balochi secessionist movement in Pakistan could spill over into its own Sistan-Balochistan province. Some Iranian officials have been skeptical about Pakistan’s commitment to cracking down on Jundallah, an armed Balochi separatist group. Tehran has alleged that Jundallah stages attacks on Iranian forces from sanctuaries on the Pakistani side of the border. Despite Iranian suspicions, Tehran and Islamabad have quietly cooperated on counterterrorism operations.

But tensions flared in late October after an armed group ambushed and killed 14 Iranian border guards. “The fact that such incidents take place on the border and bandits retreat to the neighboring country after committing their crimes make that country [Pakistan] responsible and it cannot shirk responsibility,” warned Deputy Foreign Minister for Consular and Iranian Expatriates Affairs Hassan Qashqavi. Some officials want Iranian forces to be able to pursue armed groups retreating into Pakistani territory. Neither side, however, has any interest in letting their disagreement over this issue boil over.

Moeed W. Yusuf is director of South Asia Programs at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Click here for Iran & South Asia #3: After US Withdrawal from Afghanistan

Click here for Iran & South Asia #4: Issues, Facts & Figures

Click here for Iran & South Asia #4: Issues, Facts & Figures

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org

Photo Credits: President.ir, NuclearEnergy.ir, Herat city by Fazl Ahmad (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, Iran-Pakistan Pipeline via VOA