Shaul Bakhash

On September 24, Iran’s new President Hassan Rouhani will make his debut at the annual opening of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). He is far from the first Iranian president to make this appearance. For a quarter century, Iran’s top elected leaders have all used the green marble dais in the cavernous General Assembly to lay out Iran’s vision for the Islamic Republic, the Middle East, and the world. Indeed, before becoming the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, even then-President Ayatollah Ali Khamenei traveled to New York for the opening of the United Nations in 1987.

Rouhani’s appearance this year may be particularly momentous. For the first time, both Iran and the United States are in sync about serious diplomacy -- and the bargaining may well begin in public but even more behind-the-scenes in New York. Rouhani has made clear that he will use the gathering of heads of state to announce a new era in Iran’s relations with the outside word, especially with the United States and Europe. In his brief six weeks in office, the president has already talked extensively about moderation and “constructive engagement” on international disputes.

Rouhani’s appearance this year may be particularly momentous. For the first time, both Iran and the United States are in sync about serious diplomacy -- and the bargaining may well begin in public but even more behind-the-scenes in New York. Rouhani has made clear that he will use the gathering of heads of state to announce a new era in Iran’s relations with the outside word, especially with the United States and Europe. In his brief six weeks in office, the president has already talked extensively about moderation and “constructive engagement” on international disputes. The Scottish-educated cleric has openly talked about a “win-win” deal to resolve the controversy over Iran’s nuclear program. He has vigorously defended Tehran’s right to peaceful nuclear energy, while denying that the Islamic Republic is developing the world’s deadliest weapon. But he has also pledged greater transparency to address unanswered questions about Iran’s program. With Iran’s economy in shambles, he is also looking for relief from punitive international sanctions imposed because of Iran’s failure to comply with a series of U.N. resolutions.

Rouhani will also be pressing for what amounts to a win-win compromise on Syria, Tehran’s closest ally in the Arab world. The new president has repeatedly condemned the use of chemical weapons in Syria, without blaming the government outright. The use of chemical weapons is particularly sensitive in Iran because it suffered tens of thousands of casualties from Iraq’s repeated use of several forms of chemical weapons during their eight-year war in the 1980s. But Iran has reportedly provided significant aid to the embattled regime of President Bashar al Assad. The Islamic Republic has also supported Russia’s effort to find a diplomatic outcome that will keep Assad in power. And Tehran has been outspoken in condemning a possible U.S. military strike.

Rouhani’s appearance should be placed in the context of long years of experience with Iranian engagement at the United Nations. The UNGA openings have been a forum for some of the most dramatic exchanges between Iran and the international community.

President Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

“The foundations of the security supported by such a Security Council is nothing but a nice-looking house of cards... A big chapter of our history, a very bitter, bloody and evil chapter, is saturated with American enmities and grudging hostilities toward our nation... The system of world domination makes decisions for the whole world ... yesterday it was Hiroshima and today the president of the United States is proud of the horrendous behavior of his predecessors.”

President Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, 1987

Khamenei’s attendance at the 1987 General Assembly marked the first visit by a senior Iranian official to the United Nations. Khamenei addressed fellow heads of state in the midst of the devastating Iran-Iraq war. Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s military had invaded Iran in 1980 to overthrow the fledgling Islamic Republic. Iran was isolated and resented the U.N. Security Council’s apathy toward the war. Khamenei had an opportunity to present Iran’s case.

On the day before Khamenei’s address, U.S. forces attacked the Iran-Ajr, an Iranian vessel caught dropping mines in the Persian Gulf. Five Iranians were killed and 26 crewmen were seized, four of whom were injured. Khamenei lashed out at the United States in his speech and claimed the Iran-Ajr was a merchant vessel, not a military speedboat. The incident derailed what might have been Tehran’s moment of engagement with the outside world.

On the day before Khamenei’s address, U.S. forces attacked the Iran-Ajr, an Iranian vessel caught dropping mines in the Persian Gulf. Five Iranians were killed and 26 crewmen were seized, four of whom were injured. Khamenei lashed out at the United States in his speech and claimed the Iran-Ajr was a merchant vessel, not a military speedboat. The incident derailed what might have been Tehran’s moment of engagement with the outside world. Khamenei’s words, however, reflected more than his immediate anger about the attack of the ship. Khamenei outlined his broader worldview, which centered on criticizing the prevailing international order since World War II. Khamenei begrudged the status of the five permanent U.N. Security Council members -- the United States, Britain, China, France, and Russia -- and their ability to veto resolutions. Khamenei went on to repeat his call for a change in world order as president and later as supreme leader. Rouhani’s posture will likely starkly contrast with Khamenei’s only address to the general assembly.

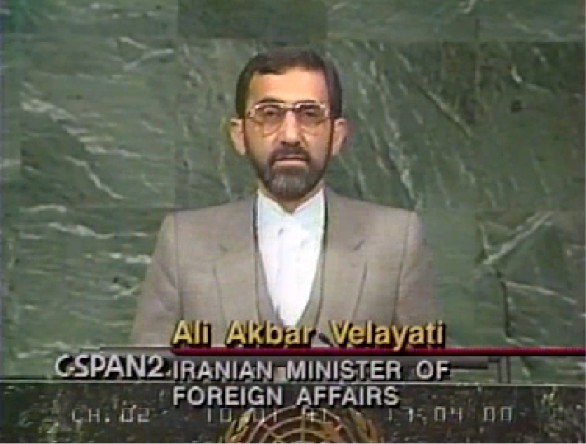

Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati

“The failure of the Security Council squarely to face the Palestinian crisis and the constant aggressions against the Palestinian people, Lebanon and Syria, not to mention its intentional failure to enforce its own resolutions, are a sad illustration of the prevailing preference of political interests over peace, security, international law and equity.”

Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati, 1993

For the next decade, no Iranian president traveled to New York to deliver a U.N. address. Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati spoke for Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, president from 1989 to 1997. Velayati served as foreign minister from 1981 to 1997 and still holds considerable influence as chief foreign policy advisor to Supreme Leader Khamenei. In his addresses, Velayati repeatedly criticized the international order and accused the U.N. Security Council of maintaining double standards. In 1992, he condemned minimal international reactions to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, “decades-old aggression” by Israel against Palestinians, and Serbia’s move against the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1996, Velayati accused the U.S. Congress of allocating money for terrorist activities against the Islamic Republic.

For the next decade, no Iranian president traveled to New York to deliver a U.N. address. Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati spoke for Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, president from 1989 to 1997. Velayati served as foreign minister from 1981 to 1997 and still holds considerable influence as chief foreign policy advisor to Supreme Leader Khamenei. In his addresses, Velayati repeatedly criticized the international order and accused the U.N. Security Council of maintaining double standards. In 1992, he condemned minimal international reactions to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, “decades-old aggression” by Israel against Palestinians, and Serbia’s move against the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1996, Velayati accused the U.S. Congress of allocating money for terrorist activities against the Islamic Republic. But President Rafsanjani was more than likely using Velayati’s addresses to exhibit strength and independence to please the Iranian public. Back in Tehran, Rafsanjani quietly enacted pragmatic policies aimed at improving Iran’s relations with the outside world. Early into presidency, Rafsanjani repaired relations with Saudi Arabia and reestablished relations with several Middle Eastern and North African monarchies. He in effect sided with the U.S.-led coalition to oust Iraq from Kuwait. And he helped win freedom for American hostages held by Lebanese allies. Rafsanjani also reached out Egypt and signed a $1 billion agreement with the U.S. oil company Conoco to develop Iranian offshore fields. But former President Bill Clinton killed the deal with an executive order that barred U.S. investment in Iran’s oil sector.

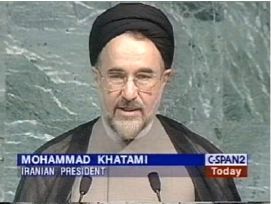

President Mohammad Khatami

“If humanity at the threshold of the new century and millennium devotes all efforts to institutionalize dialogue, replacing hostility and confrontation with discourse and understanding, it would leave an invaluable legacy for the benefit of the future generations.”

President Mohammad Khatami, 1998

When President Mohammad Khatami took office in 1997, he sincerely thought he could inaugurate a new era in Iran’s relations with the international community. In a January 1998 interview, he first outlined his idea to have a “dialogue among the nations” to promote international cooperation and understanding. He acknowledged the “bulky wall of mistrust” that had gone up between Iran and the United States since the 1979 revolution. “There must first be a crack in this wall of mistrust to prepare for a change and create an opportunity to study a new situation,” Khatami told CNN.

In September 1998, Khatami spoke at the U.N. General Assembly opening and became the first Iranian president to visit the United States in a decade. The reformist president was Iran’s one hope for better relations with the international community. Khatami’s address defied Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” thesis, which argued that culture would be the primary source of conflict in the future. But Khatami’s plans did not work out the way he intended, mostly due to domestic pressure. Hardliners did their best to disrupt and sabotage Khatami’s efforts to reach out. U.S. outreach to Khatami was too cautious. And the international community did not reciprocate the way Khatami had hoped.

In September 1998, Khatami spoke at the U.N. General Assembly opening and became the first Iranian president to visit the United States in a decade. The reformist president was Iran’s one hope for better relations with the international community. Khatami’s address defied Samuel Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” thesis, which argued that culture would be the primary source of conflict in the future. But Khatami’s plans did not work out the way he intended, mostly due to domestic pressure. Hardliners did their best to disrupt and sabotage Khatami’s efforts to reach out. U.S. outreach to Khatami was too cautious. And the international community did not reciprocate the way Khatami had hoped. Khatami, however, did achieve some success in foreign relations. He nullified Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s death decree against British writer Salman Rushdie, which had severely aggravated Iran’s relations with Europe and even led to the withdrawal of ambassadors. Khatami agreed to suspend Iran’s nuclear fuel enrichment program to allow negotiations with the Europeans to go forward under Rouhani, then-secretary of the Supreme National Security Council and chief nuclear negotiator.

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad

“Today, the Zionist regime is on a definite slope to collapse, and there is no way for it to get out of the cesspool created by itself and its supporters… American empire in the world is reaching the end of its road, and its next rulers must limit their interference to their own borders… With the grace of God Almighty, the existing pillars of the oppressive system are crumbling.”

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, 2008

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, president from 2005 to 2013, took a new approach to speaking in front of the U.N. General Assembly. The hardliner treated his appearances as an opportunity to play his preferred role as international bad boy, willing to challenge the West on almost any issue. Ahmadinejad’s inflammatory rhetoric prompted many walkouts by Western countries each year. He predicted the collapse of American power, capitalism, and Israel. In 2010, Ahmadinejad suggested that the United States orchestrated the 9/11 attacks in order to “reverse the declining American economy” and “save the Zionist regime.” In 2011, he claimed, “European countries still use the Holocaust after six decades as the excuse to pay (a) fine or ransom to the Zionists.”

Ahmadinejad also treated his U.N. audience to his bizarre religious views. He once predicted an early second coming of Jesus Christ side-by-side with the Shiite savior, the Mahdi.

Ahmadinejad also treated his U.N. audience to his bizarre religious views. He once predicted an early second coming of Jesus Christ side-by-side with the Shiite savior, the Mahdi. Ahmadinejad’s performances were aimed at a domestic audience to an extent, but more importantly to a third-world one. He tried to emulate Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and cultivate influence in developing countries. But in reality, Ahmadinejad did serious damage to Iran’s credibility and international standing with his U.N. speeches.

After eight years of Ahmadinejad’s confrontational leadership, Iran seems ready for a change in 2013. In the run-up to Rouhani’s speech, the new president has already signaled his desire to chart a new, more flexible course in dealing with the outside world. “We do not seek war with any country. We seek peace and friendship among the nations of the region,” he said in a September 18 interview with NBC. Rouhani also mentioned that he had received a “positive and constructive” letter from U.S. President Barack Obama that could be “tiny steps for a very important future.” Rouhani’s address could be the most substantive overture yet delivered by an Iranian leader to the United Nations.

Shaul Bakhash is the Clarence Robinson Professor of History at George Mason University.

Read Bakhash's chapter on the Six Presidents in "The Iran Primer."

This piece first appeared on www.foreignpolicy.com

Photo credits: President.ir, C-Span