Iran’s leaders are currently grappling with three key questions that are directly relevant to European interests.

- The first of these questions concerns how to rescue the economy and the role the West can and should play in this.

- The second centres on whether Tehran should engage in any form of diplomacy with Washington, especially after the assassination of Soleimani.

- The third focuses on whether Iran can protect its interests in the region primarily through diplomatic tools, or whether this requires a more offensive military approach. European governments that wish to persuade Iran to engage in a diplomatic process will need to absorb the lessons of internal debate on these issues.

Other Parts of the Report:

Rescuing the Economy

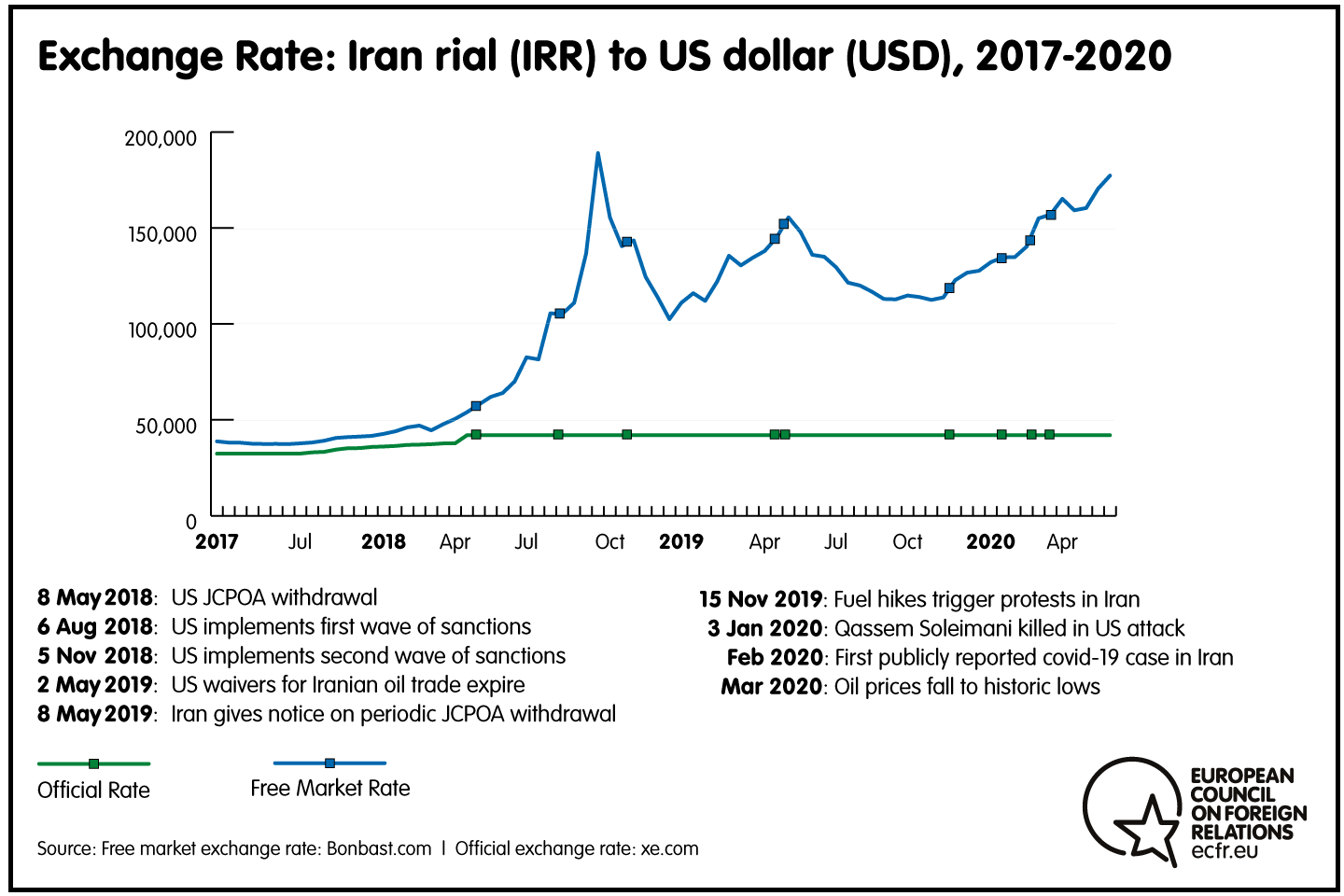

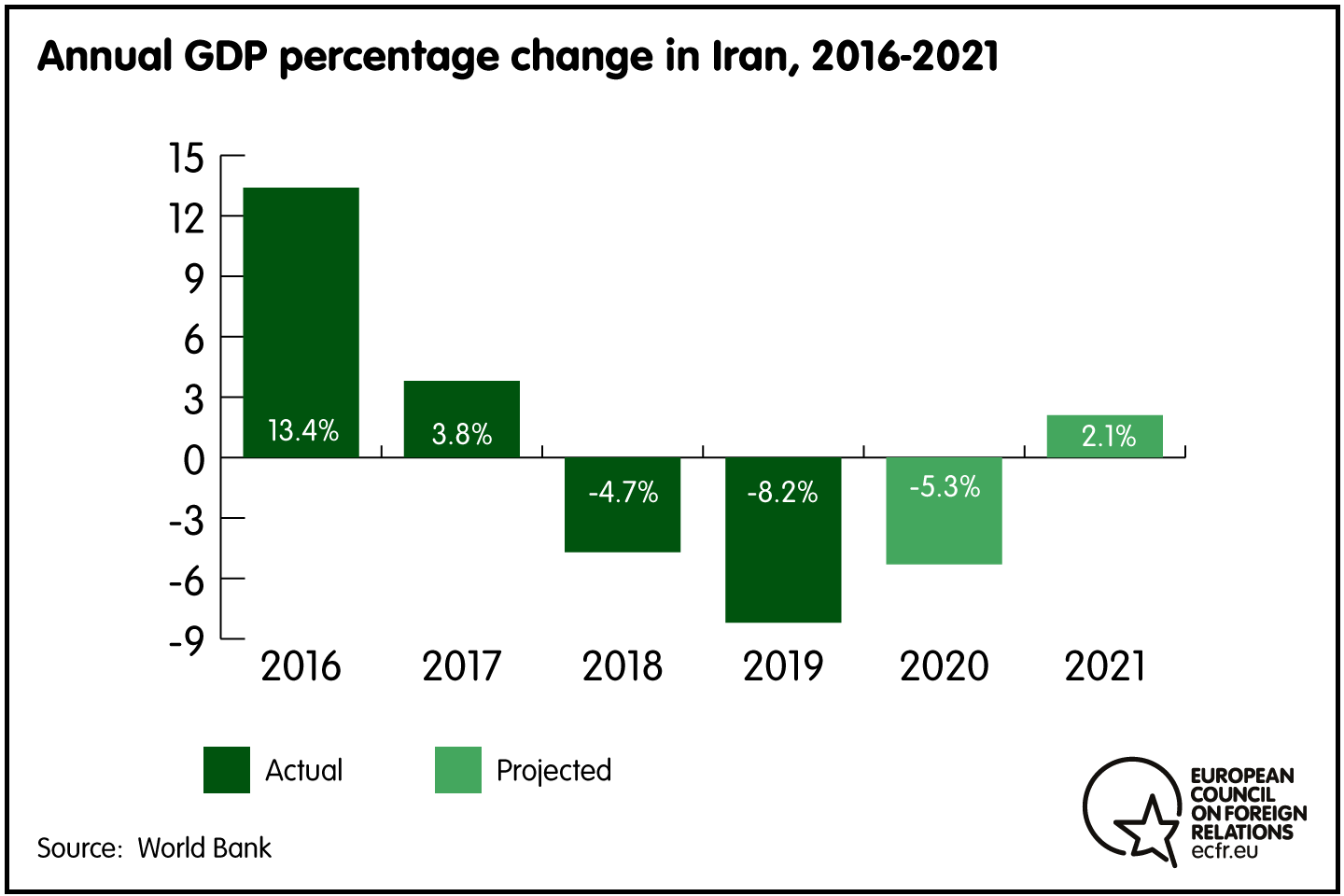

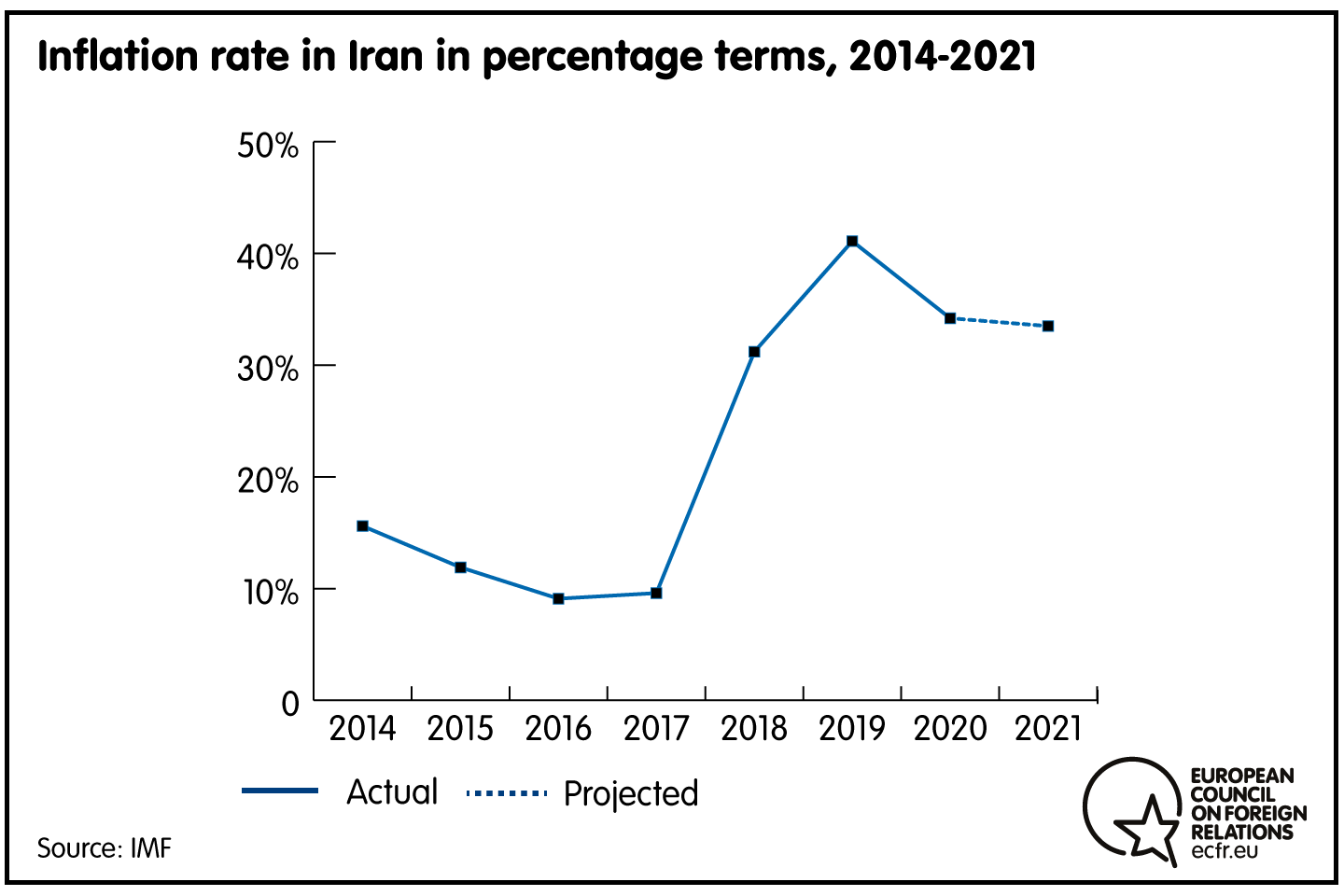

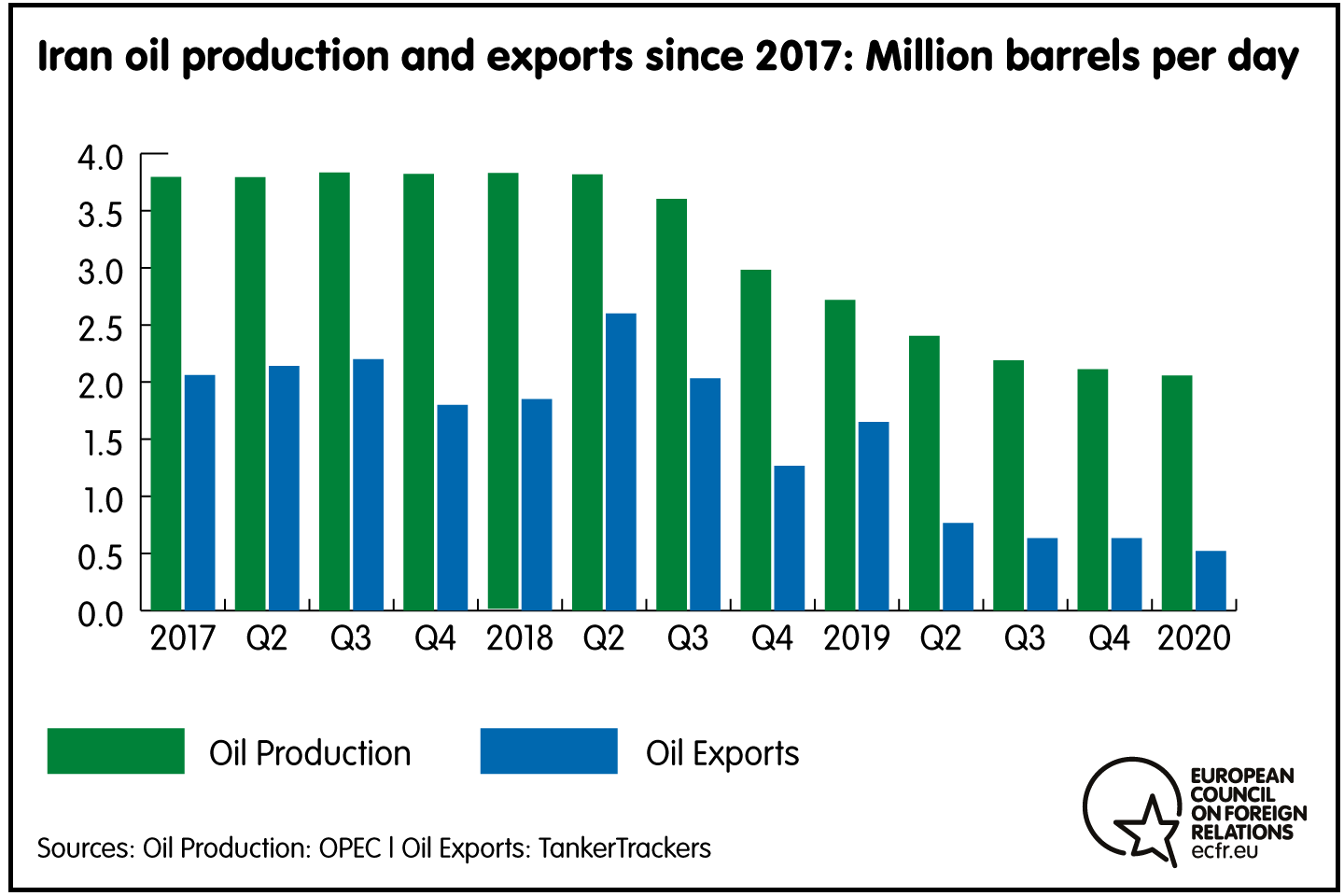

Today, the main question for Iran’s leaders concerns how to revive the country’s economy. While the economy has long been poorly managed, the last two years under the US maximum pressure campaign have been especially damaging. Iran was already grappling with reimposed US sanctions – which in May 2019 severely restricted its oil exports – before its economy was forced to deal with an unprecedented drop in oil prices and a further hit to its growth prospects following the onset of the covid-19 crisis. Iran’s economy is expected to shrink by around 5.3 percent this year. Waves of protests and unrest make this economic landscape a profound challenge for the entire ruling establishment, particularly given their sense that Washington is trying to foment unrest to bring the system down. Iran now needs to inject money into job-creating sectors in a global environment in which it cannot freely trade or raise capital.

There are two major schools of thoughts about what Iran should do. Modernisers and some traditional conservatives back a ‘modern industrialist’ approach, that favours a global economic outlook in which Iran is unhindered by sanctions and promotes privatisation and neoliberal policies. This model is based on the idea that: “Iran can only reach its potential as a regional economic powerhouse by opening up to foreign investment and technology”, as one senior economist puts it. Another expert describes this as an “economy first” vision for Iran that pursues a “theocratic version of Deng-style China, which was first introduced under Rafsanjani”.

Modernisers blame reimposed US sanctions and the maximum pressure campaign for Iran’s economic downturn. Pointing to falling trade, the Rouhani administration warns that even friendly countries that vow to defy US unilateral sanctions – such as Turkey, China, and Russia – “are afraid of purchasing [Iran’s] oil.” As such, they want to secure sanctions easing through diplomacy. This would enable Iran to receive income from the export of oil and petroleum products, access international financial markets and investment, and draw on its billions of dollars’ worth of reserves frozen in foreign banks.

“Resilient Economy” Framework

Meanwhile, the securocrats and most Principlists prefer what is known as the ‘resilient economy’ framework. This focuses on reducing the vulnerability of Iran’s economy to external pressure through improved management, increased domestic production, and techniques designed to bypass sanctions. Its proponents also argue that Iran should look to boost trade with its immediate neighbourhood, and with Russia and China. Such an approach comes with fewer political commitments involving Western actors.

Followers of the resilient economy model brand the Rouhani administration as naive for putting all its eggs in the basket of US sanctions easing via the JCPOA. As a matter of principle, they are less concerned by US sanctions; they would rather circumvent the measures than capitulate to Western pressure. In the eyes of securocrats and Principlists, the JCPOA experience proved that diplomacy will not result in any major economic transformation for Iran, and that concessions only ever benefit the West. On this basis, in January 2020, hardline members of the Expediency Council successfully blocked Iran’s implementation of FATF measures, even though the required legislation was ratified by parliament in 2018. As one expert close to the Principlists outlined, the prevalent position among this camp is that Iran should not open its books to Western institutions, as the FATF road map would have done, when it needs to maintain channels for bypassing US sanctions.

Some supporters of the resilient economy model do not even believe that sanctions have hit Iran’s economy as hard as modernisers claim: a clutch of hardline Principlists have accused Rouhani of exaggerating their impact in order to try to reopen negotiations with the US. Fundamentally, such economic questions are also political. Some supporters of the resilient economy model view it as an expression of a core revolutionary value – to put the poorest first and provide a safety net for those neglected by the previous monarchy system. Keeping Western investment out of Iran is also consistent with revolutionary aims to counter imperialism. The more politically savvy among the Principlists use the resilient economy framework and their dominance in the judiciary to attack modernisers as elitist and corrupt, while presenting themselves as providing the “jihadi management” needed to run the country.

The supreme leader has supported the resilient economy model for many years, a position that he has strengthened in the face of US sanctions. He has also favoured deepened economic ties with eastern economies, which he views as more trustworthy partners and whose leaders similarly vow to resist US sanctions. Khamenei does not deny that sanctions are detrimental, but argues that: “[Iran] cannot keep [itself] waiting on an end to sanctions … strategy should focus on creating immunity against the harms of such sanctions”. According to one economist, Khamenei is “very optimistic that, once you close the country’s doors, the economy will start high domestic production which will create jobs. He is pinning his hopes [on the idea] that ordinary Iranians will show resilience through the difficult days, like in a war front.”

It also appears that Khamenei views the securocrats as best positioned to lead Iran’s resilient economy model through greater involvement of the IRGC. One economist’s view is that, given the failed attempts to lift sanctions, the supreme leader increasingly “connects economic solutions back to the IRGC and has encouraged military forces to enter the production field.” Another economist argues that Khamenei is generally suspicious of modern industrialists, many of whom have links abroad: the “IRGC and Khamenei view themselves as [the owners] of the economy – while others are guests. The IRGC died for the country and didn’t pack up and leave because things got tough”. Benefiting from this, the securocrats have built an extensive economic network that is expected to thrive further in the sanctions environment. Shortly after the advent of the JCPOA, the modernisers led a discreet and partially successful effort to reduce the IRGC’s control in the economy. However, the return of US sanctions and exodus of foreign investors from Iran created new economic opportunities for the IRGC, particularly in the energy and automotive sectors.

COVID-19 and Sanctions Impact

Following the onset of the coronavirus crisis, the battle over the economy has begun to gear up once more. Some Principlists and securocrats are already arguing that the global recession means there is even more need for self-sufficiency. In a speech on covid-19, the supreme leader stressed that the “surge in production” should continue. But the Rouhani government has doubled down on modern industrialist approaches, floating public assets on the stock market, dipping into the country’s sovereign wealth fund, and making a rare request for a loan of $5 billion from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Some figures among the modernisers have doubled down on their public calls for Iran to find a diplomatic pathway that reconnects the country to the global economy through sanctions easing. They explicitly link this proposal to the need to manage the covid-19 economic fallout. However, lately, other moderate centrists and traditional conservatives have begun to lend their support to aspects of the resilient economy model. As economic links to the West have shrunk, through a simple process of elimination, Iran’s immediate neighbourhood has become more important than the West for economists in the modernisers’ camp. This is especially so after the Macron initiative failed to shift Donald Trump’s position on sanctions, and when European efforts to provide Iran with economic relief through the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) fell short of expectations in Tehran.

A growing number of people in Iran’s political establishment believe the current and future US administrations will either not budge on sanctions or will seek to extort such large concessions from Iran that diplomacy on economic relief becomes impossible. Overall, Iran’s modernisers see far greater value in sanctions easing and expanded trade relations with Europe, while the more hardline elements within the Principlists and the securocrats see little benefit in re-engagement with the West. Indeed, even with Iran under intense economic pressures this year, both the IMF and the World Bank project in their latest reports on the country that it will experience an economic rebound in 2021. The Principlists and the securocrats are likely to maintain that a sustained resilient economy model can make Iran immune to US sanctions pressure, as the supreme leader has called for. As such, should the Principlists gain the presidency next year, it will be far harder for Western governments to sell sanctions easing as the most attractive option to help Iran’s economy recover.

If Europe wants to persuade Iran to engage in negotiations on security issues, they should recognise that Iranian leaders will primarily look for measures that helps alleviate the economy. Europe’s best shot will be with the modernisers. However, in comparison to the previous round of negotiations in 2013, Iran’s modernisers will now be less satisfied by sanctions waivers that allow countries to purchase its oil. They will be more interested in the easing of US sanctions that block Iran’s access to global financial markets. This would enable Iran to inject substantial funds into job-creating sectors by raising capital on international markets, freely accessing international banking, and importing the technology and equipment needed for boosting local production.

This is an excerpt from a report first published by the European Council on Foreign Relations. Click here for the full text.

Ellie Geranmayeh is a senior policy fellow and deputy head of the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations.