Garrett Nada

Over the past four decades, Iran’s revolutionaries have often been targets of their own revolution. Dozens have been pushed aside, discredited, banned from running for office, or isolated. Many have ended up in jail or faced prolonged house arrest. A few have been executed. The rivalries and reprisals among disparate revolutionary factions has been the backdrop of most major political developments, in both domestic and foreign policy, in the Islamic Republic.

Among the early victims was Foreign Minister Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, a close aide to revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini during his exile. He was executed in 1982 after being charged with trying to overthrow the Islamic Republic. Abolhassan Bani Sadr, the first president after the 1979 revolution, was impeached in 1981. He went underground and fled to Paris. In 1987, Mehdi Hashemi, who had headed the Revolutionary Guards liaison with foreign Islamic movements, was executed for sedition. In 1989, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, the designated successor to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, was forced to

resign after he criticized the execution of political prisoners and fell out of favor with Khomeini.

Since the 2009 presidential election, top officials have been punished or imprisoned for ties to the Green Movement protests. Among those taken to

court in mass Stalin-esque

trials were former Vice President Mohammad Abtahi and Mohsen Mirdamadi, former chairman of Parliament’s foreign affairs committee and leader of the Islamic Iran Participation Front, a reformist party. Former Deputy Speaker of Parliament Behzad Nabavi and former government spokesman Abdollah Ramezanzadeh were also tried and convicted. All four were sentenced to jail terms.

The most famous current case involves two men who ran for president in 2009: former Speaker of Parliament Mehdi Karroubi and former Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi. Both challenged the election results, which gave President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad a second term, despite hundreds of formal complaints of voter fraud. Both were leaders of the subsequent Green Movement

protests, which raged sporadically until early 2010. Both men were put under house arrest—banished from public view or mention in the press—in 2011.

Over the past five years, hardliners have repeatedly charged both men with “sedition.” During the 2013 presidential campaign, Hassan Rouhani pledged to end the politically fraught saga. But he failed to make headway.

In a bold challenge to the Islamic regime, Karroubi issued an open

letter to President Rouhani in April 2016 pleading to be formally charged and tried. “I want you to ask the despotic regime to grant me a public trial based on Article 168 of the constitution,” he wrote. “It will show which side continues in the path of the revolution and is honorable.”

Many other revolutionaries with prestigious pedigrees have been targeted by Iran’s judiciary or security apparatus. So have their families. Three of Khomeini’s grandsons and one granddaughter have been disqualified from running in elections since 2004. The following is sampling of Iran’s political elite —reformers, centrists and hardliners — who have faced restrictions in recent years.

Khomeini Family

Ayatollah Khomeini’s name still carries great symbolic weight four decades after he led the 1979 revolution. He was the ultimate authority for a decade, until his death. Yet several of late leader’s grandchildren have been banned from running for office. At least

seven of his 15 grandchildren have been active politically since the mid-1990s. They have openly criticized laws, electoral practices or the leadership.

Hassan Khomeini, is a mid-ranking cleric and widely considered the late revolutionary leader’s heir apparent. In February 2016, the Guardian Council barred Khomeini from running for a seat in the Assembly of Experts, an 88-man clerical body charged with appointing, supervising and dismissing the supreme leader.

In an Instagram post, Khomeini’s 19-year-old son, Ahmad, charged that the Guardian Council ignored testimonies from top clerics that endorsed his father’s qualifications. The reason for the disqualification was “clear for all,” he said, implying that the council’s ruling was political. Khomeini had the backing of both reformist and centrist political elites. He appealed the rejection, but was again rejected,

reportedly for not having requisite Islamic knowledge.

The Guardian Council barred another Khomeini grandson,

Morteza Eshraghi, from running for parliament in February 2016. He is also a mid-ranking cleric.

In 2008, the Guardian Council initially barred Khomeini grandson

Ali Eshraghi from running for parliament. The council eventually

reversed its decision and reinstated Eshraghi, who was part of a reformist coalition, and some 280 other candidates. But he eventually

withdrew at the request of the Khomeini family after a smear campaign was waged against him.

In 2004, Khomeini granddaughter

Zahra Eshraghi and about 2,000 other reformists were barred from running in parliamentary elections. Eshraghi is an

outspoken women’s rights activist who is married to prominent reformist Reza Khatami, the younger brother of former President Mohammad Khatami.

Hossein Khomeini has been a rebel since the early days of the Islamic Republic. He was put under virtual house arrest in 1981 after he

charged that “the new dictatorship established in religious form is worse than that of the Shah and the Mongols.” In a 2003 BBC

interview, he claimed that his grandfather would have opposed Iran’s leaders if he were still alive. Khomeini even

supported the idea of U.S. or foreign intervention to force regime change. He was

reportedly under surveillance and banned from giving interviews to Iranian media.

Rafsanjani Family

Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, former Speaker of Parliament and two-term President (1989-1997), helped rebuild Iran after its devastating war with Iraq. He still chairs the Expediency Council. Hardliners opposed Rafsanjani’s pragmatic approach to domestic and foreign affairs, while critics alleged that his family used political connections to amass significant wealth. He was

dislodged from the Assembly of Experts chairmanship in 2011. In 2013, the Guardian Council

barred him from running for president again.

Rafsanjani’s children have also been marginalized politically. Two were charged with acting against the government after the 2009 presidential election. His daughter Faezeh Hashemi, a former Member of Parliament and vice president of Iran’s Olympic committee, was charged with “spreading propaganda.” She spent six months in prison; she was released in March 2013.

Rafsanjani’s son,

Mehdi Hashemi, left Iran after the disputed 2009 elections for Britain. He was

arrested on his return and

jailed for three months for corruption and inciting

unrest against the regime. He was released in December 2012. In 2015, he was

convicted of new charges of embezzlement, bribery and security offenses. He began serving a 10-year jail

term in August 2015.

In 2016, the Guardian Council

disqualified two of Rafsanjani’s children from running for parliament.

Fatemeh Hashemi had been outspoken in her

criticism of President Ahmadinejad’s economic mismanagement.

Mohsen Hashemi, who had served on Tehran’s city council,was also barred from running. Both had reformist views.

The Guardian Council did allow Rafsanjani to run for the Assembly of Experts, however. In February 2016, he led a slate of centrists and moderate conservatives in the Assembly of Experts

election. He placed first in the race for 16 available seats in Tehran. Rafsanjani is widely believed to covet the job of supreme leader.

Khatami Family

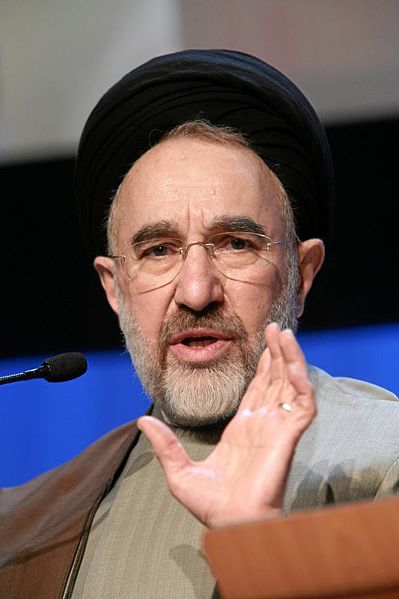

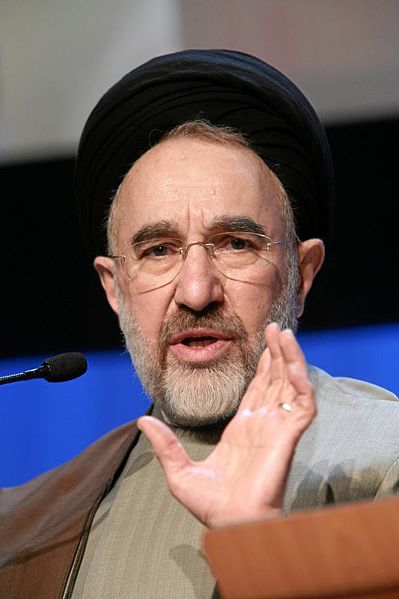

Former President

Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) pledged political and social reforms while in office, but was largely thwarted by hardliners. Since the 2009 presidential election, he has been sidelined by hardliner critics for supporting opposition leaders Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi. Since 2010, he has been banned from leaving the country and barred from public events or quotes in the media.

For the February 2016 elections, Khatami skirted the ban by using social media. He released a

video encouraging Iranians to vote for the “List of Hope” for parliament and the “People’s Experts” for the Assembly of Experts—both slates of reformers and centrists. The “List of Hope” took all 30 seats in parliament for Tehran.

The Guardian Council has tried to isolate Khatami’s younger brother,

Mohammad Reza Khatami, who was deputy speaker of parliament from 2000 to 2004. He was barred from running for

parliament in 2004. Khatami is married to Zahra Eshraghi, granddaughter of Ayatollah Khomeini. Both supported reformist candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi in the 2009 presidential election. Police

reportedly detained the couple in 2010 amid protests by the Green Movement. He is also banned from leaving the country.

Mousavi Family

Mir Hossein Mousavi served as prime minister (1981-1989) during the Iran-Iraq war. From 1989 to 2009, he served as an advisor to Presidents Rafsanjani and Khatami. In 2009, he ran for president and contested incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s victory. His protest of the official results sparked the Green Movement protests. Mousavi and his wife, women’s rights activist Zahra Rahnavard, were placed under house arrest in February 2011 for their role in the opposition.

In February 2013, the couple’s daughters

Zahra and

Narges Mousavi were

detained for

questioning after publishing a letter demanding release of their parents. Mousavi and his wife not allowed to attend the wedding of their daughter in March 2016.

Karroubi Family

Mehdi Karroubi, former parliamentary speaker (1989-1992, 2000-2004), ran for president in 2009. He too contested the official results and, with Mousavi, led the opposition Green Movement. Karroubi was particularly outspoken about harsh treatment of protestors by security forces. In February 2011, he was placed under house arrest, at the same time as Mousavi and Rhanavard. Neither has been formally charged with any crimes.

In 2009, Karroubi’s son,

Mohammad Hossein Karroubi, was

sentenced to six months in jail for speaking to foreign media about

alleged abuses of prisoners. The sentence was suspended on the condition that he not commit a crime for five years. He was

reportedly detained on Feb. 11, 2013, the same day as the Mousavi daughters.

Ahmadinejad and His Circle

Former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) began to see his status deteriorate even before leaving office. In May 2011, some two dozen individuals close to Ahmadinejad, including his chief of staff and protégé

Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei, were

arrested and charged with being “magicians.” Ahmadinejad and his cohort were labeled “the deviationist current.”

In 2013, the Guardian Council

barred Mashaei from running for president. Ahmadinejad said the decision was an act of “oppression.” He

appealed to the supreme leader to intervene, but to no avail.

In February 2015, a former vice president and top aid to Ahmadinejad,

Mohammad Reza Rahimi, began serving a five-year prison term for “acquiring wealth through illicit methods.” He was also ordered to pay compensation.

Garrett Nada is the assistant editor of The Iran Primer at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Photo credits: Abolhassan Bani Sadr by Christoph Braun (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons; Mir Hossein Mousavi by Mardetanha with special thanks to Mr.Salar Nayerhoda for kind helps (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons; Mehdi Karroubi by Mardetanha [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons; Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani via HashemiRafsanjani.ir; Mohammad Khatami by World Economic Forum (www.weforum.org), swiss-image.ch/Photo by Remy Steinegger (World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos 2007) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons; Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2009 by Kremlin.ru [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) or CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Among the early victims was Foreign Minister Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, a close aide to revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini during his exile. He was executed in 1982 after being charged with trying to overthrow the Islamic Republic. Abolhassan Bani Sadr, the first president after the 1979 revolution, was impeached in 1981. He went underground and fled to Paris. In 1987, Mehdi Hashemi, who had headed the Revolutionary Guards liaison with foreign Islamic movements, was executed for sedition. In 1989, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, the designated successor to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, was forced to resign after he criticized the execution of political prisoners and fell out of favor with Khomeini.

Among the early victims was Foreign Minister Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, a close aide to revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini during his exile. He was executed in 1982 after being charged with trying to overthrow the Islamic Republic. Abolhassan Bani Sadr, the first president after the 1979 revolution, was impeached in 1981. He went underground and fled to Paris. In 1987, Mehdi Hashemi, who had headed the Revolutionary Guards liaison with foreign Islamic movements, was executed for sedition. In 1989, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, the designated successor to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, was forced to resign after he criticized the execution of political prisoners and fell out of favor with Khomeini.  Over the past five years, hardliners have repeatedly charged both men with “sedition.” During the 2013 presidential campaign, Hassan Rouhani pledged to end the politically fraught saga. But he failed to make headway.

Over the past five years, hardliners have repeatedly charged both men with “sedition.” During the 2013 presidential campaign, Hassan Rouhani pledged to end the politically fraught saga. But he failed to make headway. Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, former Speaker of Parliament and two-term President (1989-1997), helped rebuild Iran after its devastating war with Iraq. He still chairs the Expediency Council. Hardliners opposed Rafsanjani’s pragmatic approach to domestic and foreign affairs, while critics alleged that his family used political connections to amass significant wealth. He was dislodged from the Assembly of Experts chairmanship in 2011. In 2013, the Guardian Council barred him from running for president again.

Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, former Speaker of Parliament and two-term President (1989-1997), helped rebuild Iran after its devastating war with Iraq. He still chairs the Expediency Council. Hardliners opposed Rafsanjani’s pragmatic approach to domestic and foreign affairs, while critics alleged that his family used political connections to amass significant wealth. He was dislodged from the Assembly of Experts chairmanship in 2011. In 2013, the Guardian Council barred him from running for president again. Former President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) pledged political and social reforms while in office, but was largely thwarted by hardliners. Since the 2009 presidential election, he has been sidelined by hardliner critics for supporting opposition leaders Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi. Since 2010, he has been banned from leaving the country and barred from public events or quotes in the media.

Former President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) pledged political and social reforms while in office, but was largely thwarted by hardliners. Since the 2009 presidential election, he has been sidelined by hardliner critics for supporting opposition leaders Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi. Since 2010, he has been banned from leaving the country and barred from public events or quotes in the media.