What is the status of the protest movement as Iran nears Sept. 16, 2023, the one-year anniversary of the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody?

Street protests largely subsided by early 2023. As people returned to their everyday lives, a degree of surface normalcy was restored. But as the anniversary loomed, the country was still reeling from the aftershocks of the protest movement, which began as a response to Mahsa Amini’s death after she was detained and then allegedly beaten for wearing “improper” hijab. The demonstrations soon widened to a broader uprising against the government.

A year later, Iranian society had not recovered from the trauma of the bloody crackdown in which more than 500 people died. Many families were still grieving for loved ones who were killed by security forces. Many demonstrators were suffering from injuries incurred during clashes with security forces. Some lost their sight after being shot in the eyes.

Other people, including dozens of journalists who had covered the demonstrations, were still behind bars as of September 2023. Some awaited trial; others had not even been informed of what charges they faced. Journalists who were released felt that they were under constant surveillance. A climate of fear and insecurity had set in.

University campuses remained the principal hotbeds of dissent. For example, in June 2023, students at Tehran University of Art staged a sit-in to protest a new requirement for women to wear the maqna’e, a one-piece black garment that covers the head and shoulders. Campus security beat students and detained dozens.

How did the protests evolve in 2022?

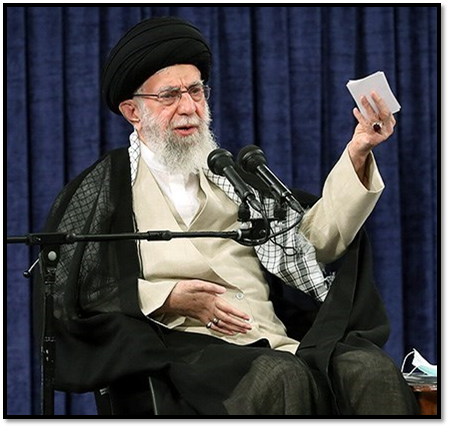

Initially, many of the protesters were women, youth or members of the ethnic minorities that had historically been subject to discrimination by the central government. Kurds in the west, Arabs in the southwest, and Baluch in the southeast were especially active. At first, demonstrators shouted slogans that were largely focused on personal freedoms. But then they started chanting against the theocracy and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The demonstrations quickly spread to predominantly Persian cities, including Tehran, as well as university campuses, high schools, and even middle schools. Young people were the most fearless. Tech-savvy members of Gen Z, the generation born roughly between 1997 and 2012, were frustrated to see how their peers in other countries—including other Islamic countries like Turkey and the United Arab Emirates—had much more personal freedoms.

Soon, broader swaths of society jumped on the bandwagon as Iranian and Western celebrities spoke out against the government. Extensive international media coverage also fueled participation in demonstrations. Iranians were willing to risk physical harm because they knew that their message was being heard across the world.

No obvious leaders emerged at the national or even the regional levels. Many prominent human rights and democracy activists had been imprisoned long before Amini’s death. The decentralized nature of the protests was a double-edged sword. The security forces were not able to round up a group of critical organizers or go after a single leader to quell the unrest. But without leaders, the protest movement lacked direction and organization, let alone a grand strategy. As a result, many of the demonstrations were highly localized and small, often just dozens of people and sometimes hundreds who gathered in a neighborhood. Security forces were able to disperse crowds and remained firmly in control.

Why did the Iranians hesitate to join the protest movement?

The brutality of the security forces was a powerful deterrent. The public understood that the government was willing to spill blood to maintain order. Members of the Basij paramilitary patrolled outside of major residential complexes in Tehran shouting threats into megaphones, including, “We saved Bashar al Assad in Syria. If necessary, we will do whatever is necessary to save ourselves. We will kill our own wives and sacrifice our children, but we will stay in power. So don’t bother hoping that you can achieve anything.”

Moreover, millions of Iranians employed by the government or dependent on state benefits were hesitant to risk their livelihoods. Getting arrested and branded as a critic of the system could have long-term impacts on job prospects. A relatively large segment of the population had grown accustomed to the status quo, which ensured a stream of income. These Iranians – including business owners in the private sector – needed the mercy of authorities to continue operating. Some saw that the situation was not tenable, and that the government was undemocratic and unaccountable. But they did not see a point in becoming revolutionaries as long as they were able to put bread on the table.

Many citizens were also simply too vulnerable to risk physical harm or retaliation by the security apparatus for joining protests that, at points, had become radical. These citizens included single mothers, youth from economically disadvantaged backgrounds who could not afford to lose work, and politically unengaged Iranians who did not see the issues as relevant to their lives.

Also, the government had a base of supporters. They were not small in numbers. This base was eroding steeply, and frictions were emerging, which showed that the government’s unvarnished repression had alienated many loyalists—especially those whose allegiance to the Islamic Republic was anchored in religious values. Some were realizing that the government that claimed to represent God did not flinch from unleashing violence and mistreating its own people, so they were losing faith in the system.

But this trend was not an overnight development. Whoever underestimates the masses of Islamic Republic devotees—even with its unbridled democratic backsliding and authoritarian metastasis—does not understand the complex dynamics of Iranian society.

How did the 2022 protests compare to previous rounds of demonstrations in 2009, 2017-18, and 2019? What was unique or different?

The 2022 protests were unique in four major ways. First, the driving force – a demand for greater civil liberties – was different than in the previous rounds of protests. The 2009 demonstrations were over the disputed reelection of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Millions of Iranians took to the streets to demand government accountability. The rallying cry of the Green Movement was, “Where is my vote?” The demonstrations in 2017-2018 and 2019 were driven by economic grievances.

The 2022 protests, ironically, were much more reminiscent of the 1979 revolution against the Shah in that the government was refusing to listen to the people and was projecting its invincibility through force.

Second, the demographics of the protesters were much more diverse in 2022. Virtually all sectors of society participated. Amini’s background as a double minority—a Sunni Kurd—did not matter. Her death and the call for greater personal freedom resonated across ethnic, sectarian, class, and rural versus urban divides. In contrast, the 2009 protests were largely fueled by members of the urban, educated middle class, especially the youth. In 2017-2018 and 2019, many of the protesters were young men who were directly impacted by poor economic conditions and skyrocketing prices.

Third, the geographic spread of the 2022 protests was unprecedented. Demonstrations were reported in nearly 200 cities and towns across all 31 provinces. Even people in peripheral villages with no notable record of political activism demonstrated. In contrast, the 2009 protests were concentrated in a few dozen major cities, especially Tehran. The 2017-2018 protests reportedly spread to some 160 cities. The 2019 protests reportedly spread to at least 100 cities and towns.

Fourth, the frequency, duration, and size of the 2022 protests was different. They were sporadic and small but happened almost daily for more than three months. In major cities and university campuses, hundreds of people gathered. But demonstrations in towns and villages often only included dozens of people.

By contrast, the 2009 Green Movement, nominally led by presidential candidates Mir Hossein Mousavi, a former prime minister, and Mehdi Karroubi, a former speaker of parliament, were more organized. Days or weeks sometimes passed between demonstrations, but they tended to be very large. Hundreds of thousands turned out. At the movement’s height, nearly three million people took to the streets of Tehran. The 2017-2018 and 2019 protests were sporadic, but they only lasted for about two weeks.

What measures did the government and security forces take to quell the protests? Did the tactics evolve?

During the first few weeks of demonstrations, the government hesitated to authorize a heavy-handed crackdown. Officials seemed to understand that people needed to vent their frustration and anger. Security forces avoided physical confrontations with demonstrators or even appeared to join protesters in some videos posted on social media. Others appeared to use rubber bullets and tear gas more often than live bullets.

But the strategy quickly changed. The government ran out of patience, perhaps due to the increasingly radical calls for the downfall of the government and death of Supreme Leader Khamenei. Plainclothes officers, Basij paramilitary members, and eventually the Revolutionary Guards deployed to the streets in force. Their tactics were especially brutal in Kurdish and Baluch areas. On Sept. 30, 2022, security forces reportedly killed at least 66 people in Zahedan, the capital of Sistan and Baluchistan province, after Friday prayers. In December 2022, authorities carried out the first protest-related execution as a warning to demonstrators. Mohsen Shekari, a 23-year-old male café worker, was charged with blocking a street and assaulting a security officer during demonstrations in late September.

By early 2023, at least 500 people were reportedly killed and 20,000 people had been detained. The government did not detain nearly as many people during other periods of unrest. Prisons were overcrowded.

Aside from brute force, the government also disrupted communications. It restricted access to Instagram and WhatsApp, popular social media platforms. It directed internet service providers to cut mobile data in the evenings, which made it more difficult to upload photos and videos of protests in real time. Sometimes, the government also slowed down internet connections for homes and businesses.

What impact did the protests have – socially, politically and economically?

The most visible social impact of the protests was thousands of women defying the mandatory dress code by appearing in public without hijab. Women across the country, not just in affluent north Tehran, refused to return to the status quo ante even after the protests died down. Some actresses stopped appearing in movies and television shows to avoid having to wear a hijab and go against their values. Generally, people became much more willing to engage in civil disobedience at the individual level.

The demonstrations and government crackdown politicized younger generations of Iranians. Middle and high school students, even if they did not participate in protests, could not avoid the debates on television, in newspapers, at schools and in homes. Even youth in marginalized, underdeveloped provinces became more aware of what was going on and the lengths to which the government was willing to go to enforce a rigid social code and maintain power. The impact of the early exposure to state-sanctioned violence and debates about the role of the government may have far-reaching consequences.

The protests also created a new sense of unity among Iranians of different backgrounds who came to the realization that the status quo was not sustainable. Notably, some regime loyalists took to social media to say that the demonstrator’s demands were legitimate, and that the government had lost its moral authority in the crackdown.

The economic impact of the protests was difficult to quantify. Sporadic strikes by small businesses, bazaar shopkeepers, and contract oil workers did not appear to have an effect at the national level. But the protest movement did lead to a division between two parts of society: people who were economically reliant on the government and people who were more independent. Consumers started being more particular about where they were purchasing goods and services. Supporters of the protests were less likely to frequent businesses, malls, and restaurants with staff and security guards who admonished women for foregoing the hijab or wearing it “improperly.” Other business owners, especially in the tourism and entertainment industries, were willing to risk being shut down or fined to give their clientele a sense of freedom.

The crackdown on protests also triggered a new wave of emigration. Iranians who were fed up with the lack of personal freedoms, especially artists, educators, and academics, sought opportunities abroad. The departure of talented and educated Iranians, a brain drain, was a loss for the economy and sapped the resources of an already strained society.

Has the government offered concessions on enforcement of the dress code? What are the prospects for reforms on the issue of hijab and personal freedoms?

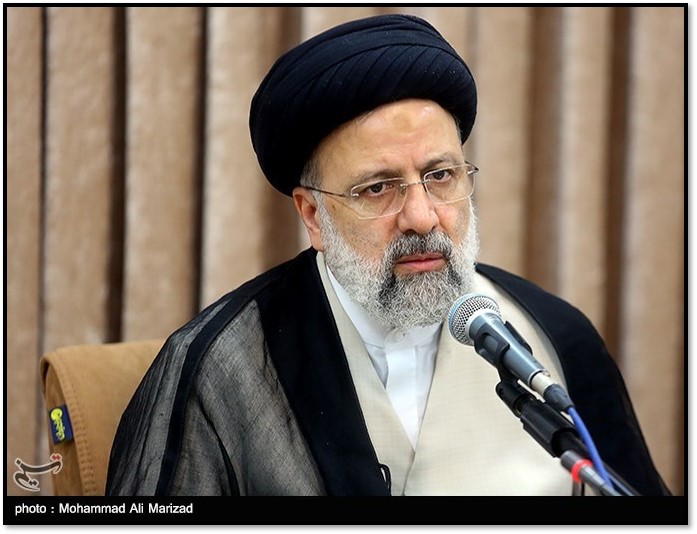

Prospects for compromise on the part of the government, dominated by hardliners, were slim to none as of September 2023. The supreme leader, the president and other senior leaders considered the hijab to be a pillar of the Islamic Republic. They feared that compromise on the dress code could weaken the theocratic system by legitimizing calls for broader reforms.

At one point, Supreme Leader Khamenei offered some seemingly conciliatory language about the hijab. “The hijab is a religious and inviolable necessity, but this inviolable necessity should not mean that someone with not a full hijab should be accused of anti-religion or anti-revolutionary,” he said on Jan. 4, 2023. But his actions three days later made clear there would be no significant concessions. Khamenei appointed Brig Gen. Ahmad Reza Radan – an ardent supporter of the morality police known for harsh tactics – to head the national police.

Khamenei’s branding of hijab violations as “political haram” (forbidden by Islamic law) on top of being “religious haram” signaled to many Iranians that the establishment considered dress code compliance a national security red line. By drawing a redline, the government has effectively transformed a personal preference for dress into an act of defiance and a blueprint for political expression. It turned more constituents against itself, as a result. The continued insistence on enforcing compulsory hijab—as well as the round-the-clock bloviating of the authorities about the importance of hijab—only deepened the chasm between the establishment and the public, instead of cementing the central government’s authority.

President Ebrahim Raisi’s mentality was glaringly stuck in the 1980s. He thought that he could govern Iran using the same tools of repression from his time in the judiciary and the same principles that defined the early years of the Islamic Republic. In the year after Amini’s death, Raisi continued to harp on tired tropes, such as the “blood of martyrs” and “striving for a pure Islam,” which even many religious Iranians believed was a betrayal of those concepts. He was completely detached from contemporary Iranian society, especially the lifestyle, interests and demands of Gen Z and millennial protesters. Raisi even alienated traditional supporters of the Islamic system. For example, many young clerics, who were active on Twitter, have started reconsidering their loyalty to the government because of the widespread disparities and inequities they see in Iran.

The 2022 demonstrations caused the government to become hyper-focused on the issue of hijab enforcement. In April 2023, authorities started installing cameras in public places to identify unveiled women. In July 2023, the government redeployed the morality police after they were largely absent from streets for several months. The morality police started patrolling metro stations, museums, concert halls, shopping centers, and many other public spaces, although officers were less confrontational than in prior years. Authorities also shut down and fined businesses for not enforcing the mandatory dress code for women.

In July 2023, Parliament published the draft of the “Hijab and Chastity Bill,” which outlined harsher penalties, including imprisonment and fines, for dress code violations. The draft text, which included 70 articles, even called for increased gender segregation in hospitals, universities, parks, and other places. Lawmakers voted 175 to 49 on August 13 to debate the bill in a special committee behind closed doors rather than on the floor of Parliament. After the committee finishes the draft and Parliament gives the final nod, the bill would need the approval of the powerful Guardian Council. It would then be implemented on a trial basis for three to five years. Parliament could then make the law permanent.

What are the prospects for another round of protests?

The government’s policies created the conditions for another outburst of public anger. The atmosphere was increasingly securitized due to the invasive patrols of the morality police. Many Iranians, especially women who refused to don the veil again, felt suffocated. And the clampdown on businesses for not enforcing the dress code put pressure on a new stratum of society.

In the runup to the anniversary of Amini’s death, the Revolutionary Guards warned of reprisals and touted their prowess in maintaining order. But the government, by injecting ideology and preaching to people in schools, at workplaces, and at home through state media, was creating a ripe environment for renewed protests.

Kourosh Ziabari is an award-winning Iranian journalist whose writing have appeared in Foreign Policy, Asia Times, New Lines Magazine, Al-Monitor, The New Arab, and Middle East Eye, among others. In 2022, he covered the United Nations on a Dag Hammarskjold Fund for Journalists Fellowship. In 2022, he became the first Iranian to be selected as a World Press Institute fellow by the University of St. Thomas since 1979. Ziabari is originally from Rasht, Iran.