Nasser Hadian is a U.S.-educated professor of political science at the University of Tehran and a former visiting professor at Columbia University.

Does Iran really want to return to the nuclear deal? Why—or why not?

Yes, both Iran and the United States want to go back to the nuclear deal—though not out of love for it. Restoring the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) is in the mutual interest of both countries. Both sides know that the risk of conflict and even a regional war will increase if they do not reach an agreement.

Unfortunately, both Tehran and Washington are misreading each other. They have accused each other of not being serious in the Vienna talks. U.S. officials and policymakers think that the Iranians do not want to go back to the deal and are providing excuses. They think the Iranians are buying time to advance the nuclear program.

The Iranians have concluded that the Americans are not looking to restore the JCPOA, despite what they say publicly. The Iranians see the diplomacy as an American public relations campaign to blame Iran for the failure of the deal and for not abiding by it.

What specifically does Iran want from the United States at the Vienna talks?

The first priority is ensuring the sustainability of the nuclear deal. Iran wants to make sure that whoever is president after Biden cannot withdraw from the JCPOA. A few ideas have been discussed in Iran: Some suggest that Biden issue a written statement committing to staying in the deal as long as he is in office—and encouraging the next president to stay in the deal. Others suggest that the Senate ratify the JCPOA as a treaty, but the Iranians also know that ratification is not workable and maybe impossible given the current composition of the Senate.

I told officials under former President Hassan Rouhani and current President Ebrahim Raisi that they should not waste time trying to get these kinds of assurances. A statement from Biden would not mean anything to someone like Donald Trump or other Republicans who may run for president in 2024 and who share Trump’s views. They might still withdraw from the deal.

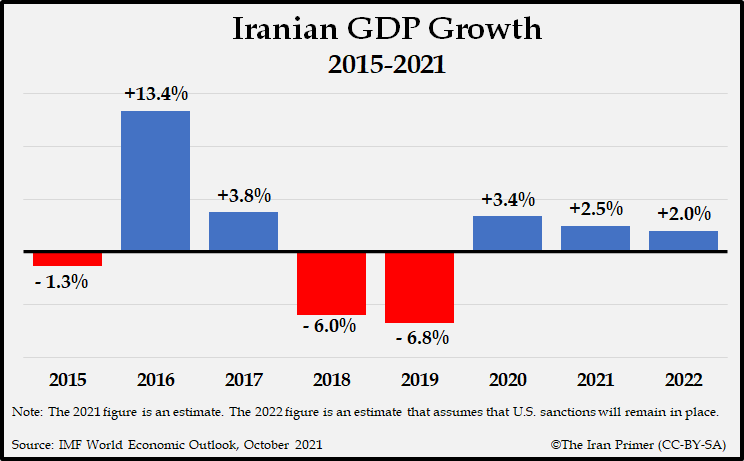

Iran’s second concern is securing the economic benefits promised under the JCPOA. In February 2021, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said that the United States “must completely lift sanctions, and not just in words or on paper” before Iran returns to full compliance. Iran wants to make sure that U.S. sanctions are lifted in practice to avoid a repeat of what happened after the U.S. withdrawal from the agreement, when Trump imposed more than 1,000 new sanctions. The Europeans, Russia and China condemned the U.S. move but essentially abided by the reimposed sanctions. As a result, the heads of major international companies decided that investing in Iran was not worth the risk of facing secondary U.S. sanctions. And banks wanted nothing to do with Iran’s money.

Iran’s third concern is compensation for the economic damage caused by U.S. sanctions. Iran’s government has estimated that the sanctions cost more than $240 billion. The Iranian negotiators know that the Biden administration, due to U.S. domestic politics, cannot directly grant compensation.

Iran’s third concern is compensation for the economic damage caused by U.S. sanctions. Iran’s government has estimated that the sanctions cost more than $240 billion. The Iranian negotiators know that the Biden administration, due to U.S. domestic politics, cannot directly grant compensation.

But compensation could come in other forms. For example, in 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron proposed extending $15 billion in credit lines if Iran came back into compliance with the JCPOA. Any compensation plan could be discussed by the Joint Commission, the body tasked with overseeing implementation of the deal.

Iran’s fourth concern is amending the so-called “snapback” mechanism through which U.N. sanctions can be reimposed on Iran. U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231, which endorsed the JCPOA, included a clause that would allow any state to call for the reimposition of U.N. sanctions for Iran’s “significant non-performance of commitments.” The Security Council would then have 30 days to pass a new resolution rejecting the complaint and recommitting to sanctions relief. Iran’s concern is that the United States—or any of the other four permanent members of the Security Council—could then veto that resolution.

Iran reportedly added three pages of new stipulations of what it wanted from the United States. What did they include? And why?

The new negotiating team under President Raisi presented two texts, one on sanctions relief and one on the nuclear program. I have not seen the documents, but the main point is that they demanded more concessions than the team that represented President Rouhani in the first six rounds of talks between April and June in 2021.

President Raisi’s team has been under tremendous pressure at home. Critics have said that the diplomats are inexperienced in international negotiations and lack the requisite expertise. So they want to prove to the Iranian public that they are as capable, if not more so, than their predecessors. They need to show that their demands have been taken seriously in Vienna and somehow incorporated into the working draft. Also, the lead negotiator, Deputy Foreign Minister Ali Bagheri Kani, was a vocal critic of the JCPOA. So he has to press for changes to maintain his credibility.

Given the difference in expectations, how might the United States and Iran compromise?

One way to ensure the sustainability of the deal would be for Iran to store all of the new materiel—including more advanced centrifuges and a stockpile of enriched uranium that exceed the JCPOA’s limits—produced and used since the United States withdrew from the deal. The equipment and material could be sealed and monitored by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

This compromise is the least bad option to save the JCPOA. And it would benefit both sides. The arrangement would allow Iran to retain its strategic assets but under international supervision. It might also deter the next U.S. president from withdrawing from the JCPOA, because if Washington abandoned the deal, Tehran might then be free to break the seals on equipment and quickly advance its nuclear program. Technically, this arrangement goes beyond the deal’s original terms. But from Iran’s perspective, the United States must make concessions because it withdrew from the deal in 2018.

This compromise is the least bad option to save the JCPOA. And it would benefit both sides. The arrangement would allow Iran to retain its strategic assets but under international supervision. It might also deter the next U.S. president from withdrawing from the JCPOA, because if Washington abandoned the deal, Tehran might then be free to break the seals on equipment and quickly advance its nuclear program. Technically, this arrangement goes beyond the deal’s original terms. But from Iran’s perspective, the United States must make concessions because it withdrew from the deal in 2018.

Iran could reciprocate with a concession. For example, it could extend some of the so-called “sunset clauses”—the designated years, between 2023 and 2031, when Iran could resume nuclear activities—by a couple of years. Alternatively, Iran could allow more extensive IAEA monitoring or compromise on the less sensitive sanctions.

What are the alternatives if diplomacy fails?

The United States has considered enforcing sanctions more stringently and pressuring the Chinese to stop buying Iranian oil. But these moves would not change Iran’s strategic calculus. The United States could also consider deploying more soldiers, aircraft carriers or bombers to the region to add military pressure on Iran. In turn, Iran could marshal its allies in the region to pressure U.S. forces. The risk for miscalculation or misperception by either side, however, could greatly increase. An incident or a miscalculation could quickly spiral out of control.

A U.S. or Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities also could trigger a regional war with terrible consequences for many other countries, including Israel, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. Iran has already planned for this scenario.

How do Israeli warnings of a potential military strike play into Iran’s calculus?

An Israeli strike could convince more Iranians of the need to produce a nuclear weapon. Now, only a tiny minority of hardliners think that Iran needs a bomb, but a strike could change that very quickly.

Has Iran’s strategy or goals changed under President Raisi? If so, how? And why?

Iran’s strategy and goals have not shifted dramatically under Raisi. The key difference is that many officials in the new government, which is dominated by conservatives or principlists, were critics of the JCPOA. But views vary within the Raisi government about the diplomats who negotiated the deal in 2015.

The most extreme view is that the Rouhani-era diplomats were traitors or spies that played into a U.S. plan. At the opposite end of the spectrum, others consider the earlier Iranian diplomats to be naïve for trusting the Americans; as a result, they negotiated a bad deal for Iran. This is part of the reason why the new negotiating team made more demands than their predecessors.