In 2020, Iran’s myriad challenges – political, economic, environmental and from the coronavirus pandemic – converged in oil-rich Khuzestan province. In May, protests in the province, home to Iran’s restive Arab minority, flared over unpaid wages and growing water scarcity. On May 23, security forces used tear gas and plastic bullets to disperse a protest over a drinking water shortage near Ahvaz, the provincial capital. Parts of Khuzestan—for decades a fertile breadbasket for wheat, corn, rice and sugar—have turned into a dustbowl because of climate change and government mismanagement, including inefficient dams.

Among Iran’s 31 provinces, Khuzestan was one of the hardest hit by COVID-19. In May, a second wave of infections forced several counties to reimpose lockdown orders. By early June, infections in Khuzestan accounted for about quarter of Iran’s total daily cases. Nearly 600 people had died and more than 13,000 were infected, according to Johndi Shapour University of Medical Sciences.

Among Iran’s 31 provinces, Khuzestan was one of the hardest hit by COVID-19. In May, a second wave of infections forced several counties to reimpose lockdown orders. By early June, infections in Khuzestan accounted for about quarter of Iran’s total daily cases. Nearly 600 people had died and more than 13,000 were infected, according to Johndi Shapour University of Medical Sciences.

Iran’s economy and national security depend on stability in Khuzestan, a province on the southwest border with Iraq that is about the size of West Virginia. It is the most important province economically and strategically. It is Iran’s “Achilles tendon,” the CIA reported.

Khuzestan is responsible for some 16 percent of the gross national product, second only to Tehran province. But it has not benefitted proportionately from government investment. In 2016, the deputy minister of Economy, Cooperatives, Labor and Social Welfare acknowledged that Khuzestan was underdeveloped “despite being rich in resources of water, gas, oil, petrochemicals and various industries.”

Khuzestan is home to some 80 percent of Iran’s onshore oil reserves. In November 2019, Iran announced the discovery of giant oil field in Khuzestan with 53 billion barrels, which could increase its reserves by a third. In August 2020, it also plans to open the largest gas refinery in the Middle East in Khuzestan. The province has historically been the top producer of wheat and one of the largest producers of corn and rice. As of 2017, the province had the largest area of harvested land and produced the most grain and legumes. Khuzestan is also responsible for much of Iran’s sugar beet and sugar cane. It is also home to the country’s biggest steel exporter.

Politically, Khuzestan originally became part of the Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great in the 6th century B.C. but came under Arab control after early Muslims swept through the Gulf in the 7th century. It became a semi-autonomous Arab emirate—known locally as Arabistan—until it was incorporated into a centralized Iranian state in 1925. Arab separatists now consider the province, which they call Ahwaz, to be under Persian occupation. Arabs are estimated to make up between two and four percent of Iran’s 84 million people, but Arabs account for a majority of Khuzestan’s 4.7 million population. Many of Khuzestan’s problems stem from or are worsened by ethnic tensions between Arabs and the Persian-dominated central government.

Khuzestan is one of three border provinces that the central government has neglected for decades, according to Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran. Kurdistan province, in the northwest, is home to the Kurds; Sistan and Baluchistan province, in the east, is home to the ethnic Baluch.

“Iran, both before and after the 1979 Revolution, has made a big mistake by treating all kinds of problems and grievances in these provinces with a heavy-handed national security approach, as potential gateways for separatism or invasion,” Ghaemi said. “Khuzestan was the front line of the Iran-Iraq War. The province’s residents have legitimate grievances that have been exacerbated by the government’s overreaction to separatists. In my 20 years of tracking executions in Iran, Arab and Kurdish prisoners are executed much more frequently than others.”

Related Material

Environmental Issues

Khuzestan is on the eastern edge of the Fertile Crescent, a historically verdant region stretching across the Middle East. The province is rich in fresh water resources, but a combination of poor policy decisions and climate change have severely degraded the environment. “Khuzestan used to have a third of the country's water resources with five major rivers,” Sayed Sharif Hosseini, a member of parliament from Ahvaz, said in 2012. “Today, our province is facing problems in drinking water and agriculture.”

Iran’s longest and only navigable river, the 515-mile-long Karoun, passes through Khuzestan and its capital. But the Karoun – along with Iran’s third longest river, the Karkeh – has been gradually drying up for more than decade. In January 2020, islands appeared in the middle of the Karoun as the water level dropped.

Khuzestan’s climate has been warming and becoming increasingly arid for years. In 1958, annual precipitation in Ahvaz was 11 inches compared to just 3.5 inches in 2012. Temperatures can reach well beyond 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer, which makes the region prone to wildfires. In 2017, the temperature in Ahvaz hit 129 degrees – Iran’s highest temperature on record at the time. High temperatures have increased the risk of wildfire.

Government Planning

Policy decisions, however, have had a bigger impact on the environment than climate change, according to David Michel, a senior researcher at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. “In Iran, power over water resides with the central government. Its agricultural policies aim to foster food security and agricultural self-sufficiency, enshrined in Article 3 of Iran’s constitution,” he said. Prioritizing agriculture, which accounts for some 90 percent of water usage in Iran, has heavily taxed the environment.

%20border.jpg)

Since the 1970s, Iran has built more than a dozen dams in Khuzestan to manage seasonal flooding, generate hydroelectric power, irrigate crops and supply other provinces with water. Iran has since recognized that many dams have done more harm than good.

“We made these mistakes in the 1980s. Then we came to realize that in places that we'd built dams, we shouldn't have built any, and in places where we should have built dams, we didn't build any,” Isa Kalantari, the head of Iran’s Environment Department, said in 2018. Some of the dam reservoirs in Khuzestan are often empty. The have also caused or exacerbated environmental degradation. For example, the Gotvand Dam, completed in 2012, was built on salt beds that made the water in the reservoir unfit for irrigation.

Dust Storms and Floods

The drying of wetlands and rivers has increased the province’s proneness to dust storms. Dust storms have been common for more than a decade and have been building in intensity. As the wider Middle East warms, dry soil is easily picked up by the wind and crosses international borders. Dust originating in the deserts of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq can cross into Iran. The resulting storms can blot out the sun and bring cities to a standstill. They disrupt commerce, education, agriculture and transportation.

Dust has long plagued the provincial capital and its 1.2 million residents. Some 76,500 tons of dust was dumped on Ahvaz in 2016 and 2017. Thousands of people visit hospitals with respiratory problems each year. Ahvaz was the world’s most polluted city, according to the 2011 World Health Organization index on air quality. In 2015, the Iran’s Department of Environment reported that Ahvaz was its most polluted city.

Dust is a bigger problem than industrial pollution or car exhaust. One local study, published in 2013, analyzed coarse particulate matter (PM10) concentration, a standard indicator of pollution, in Ahvaz’s air. Mineral dust accounted for 41.5 percent of PM10, followed by petrochemical industries and fossil fuel combustion (13 percent) and vehicle exhaust (11.5 percent). The World Health Organization’s guideline for PM10 concentration is 50 micrograms per cubic meter over the course of 24 hours. In Ahvaz, however, PM10 concentration has sometimes surpassed 10,000 micrograms per cubic meter – beyond levels that the Department of Environment’s sensors can measure.

In February 2017, a particularly bad spate of dust storms knocked out power and water supplies in Ahvaz. Hundreds of protestors gathered in front of the governor general’s office to demand government action. “My grandchild, wife and I are all suffering from respiratory diseases,” one protester said. “When the storm hits the city, we have to shut the windows and draw the blinds and can’t leave the house for some days and we feel like prisoners who live in small and dark cell.” Demonstrators waved placards, “Don’t kill Khuzestan,” “Ahvaz in blackout,” and “Karoun river is dead.”

The signs in the foreground read "Don't turn Khuzestan into hell by transferring water."

The government has been slow to act. In 2018, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei approved the withdrawal of $150 million from the National Development Fund to counter dust pollution and upgrade electricity infrastructure in Khuzestan.

Khuzestan’s dry soil has left it especially vulnerable to flooding. In March and April 2019, flash floods hit 28 out of 31 provinces. The Dez and Karkeh rivers overflowed and dams were opened as they reached capacity. The floods impacted some 400,000 people, displaced 46,000 and killed six in Khuzestan. Some 772 square miles (200,000 hectares) of farmland were flooded. Small-scale protests against the government’s poor preparation and response were held from April 12 to April 14 in and around Ahvaz. Demonstrators chanted “Khuzestan has been washed away and [our] leaders have fallen asleep!”

Water Shortages

Since much of Khuzestan’s river water is redirected to other provinces or used in agriculture and industry, little is left for Khuzestan’s residents. Much of the water that flows downstream is unfit for drinking, and the province does not have adequate water treatment plants. Only 20 percent of wastewater produced by the eastern half of Ahvaz is treated each year, and the rest flows directly into the Karoun river.

Drinking water shortages have sparked demonstrations across the province. In June and July 2018, protests broke out in Abadan and Khorromshahr over the high salinity of drinking water from the Bahmanshir river. Hundreds were arrested and four demonstrators were reportedly killed. Abadan’s water had to be rationed.

On May 23, 2020, residents of the rural Gheizaniyeh district of Ahvaz gathered in front of the governor’s office and then blocked a major road to protest chronic water shortages. They burned tires and clashed with police who reportedly used tear gas and plastic bullets to disperse the demonstrators.

In a rare act of contrition, the Supreme Leader’s provincial representative, Seyed Abdolnabi Mousavifard visited a young man who was badly injured in the leg by plastic bullets. “I’m here to apologize to this young man,” Mousavifard said in a video published by Fars News Agency. President Hassan Rouhani told the energy minister and Khuzestan’s governor to immediately solve the water problem.

Economic Issues

In the 1980s, the border province witnessed some of the toughest battles during the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq in cities such as Ahvaz, Dezful, Khorramshahr and the port city of Abadan. Government efforts to rebuild Khuzestan after the war did not prioritize local concerns. In 2020, the province’s infrastructure was aging and inadequate, and the quality of health, education and other social services was poor, especially in rural areas.

In August 2019, Khuzestan’s unemployment rate was 14 percent – more than three percent higher than the national average, according to Hamid Pourmohammadi, the deputy minister of economic affairs. Economic frustrations boiled over in November 2019 after the government’s overnight announcement of a gas price hike.

Demonstrations first broke out in Khuzestan and then swept the country. The price change “was only an excuse for us to help get rid of the fire in our hearts and instead set fire to the unjust establishment,” an unemployed protestor told the Financial Times. “There is no injustice bigger than sitting on an ocean of oil and gas and even seeing oil wells from your houses but struggling with . . . unemployment.”

The dire environmental conditions have also triggered a “dust bowl” migration. Some 240,000 people migrated from Khuzestan from 2011 to 2016. Local officials have warned of a provincial brain drain. “Within 20 years, all of Khuzestan’s residents will have left,” said Hedaytollah Khadami, a lawmaker, in 2018.

In 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak caused further job loss. More than 30,000 people applied for unemployment by early May. During the same month, municipal workers in Arvand Kenar and Khorramshahr protested five and four-month delays in payments of their wages, respectively.

Corruption

Political and economic elites from other provinces have taken advantage of Khuzestan’s residents for decades. Many businesses in Khuzestan import labor from other provinces instead of employing locals. The locals who are hired are often poorly paid day laborers. Arab activists have claimed that the government confiscates property to use for development projects.

Since the 2000s, the government has been privatizing steel mills and sugar factories. Children and relatives of military commanders, prominent clerics and officials have reportedly acquired businesses in shady deals. Prominent ayatollahs in Qom have also gained major stakes in sugarcane and other cash crops, according to Ghaemi.

Haft Tappeh Sugar Mill is a microcosm of the exploitation and corruption that has long plagued Khuzestan. The mill was built in the 1960s on land reportedly confiscated from Arab farmers who were poorly compensated financially, but promised that their children could work in the mill. The next generation only ended up working as day laborers, however. The factory’s waste also polluted the surrounding area to the detriment of palm farmers and fisherman. Water near sugar mills was usually extremely salty and polluted with pesticides and waste.

The mill has been poorly run since it was privatized in 2015. By 2017, the factory had accrued some $90 million in debt. The owners reportedly withheld wages and pensions to pay off the debt. Workers subsequently went on strike several times after going unpaid for months at a time. Dozens have been arrested for protesting.

Esmail Bakhshi, the spokesman of the factory’s workers union, said that he was tortured after his arrest in November 2018. One seasonal worker committed suicide after repeatedly being denied his wages. A 25-year old activist was sentenced to five years for demonstrating. The government punished labor activists for “exercising their collective bargaining rights and conducting peaceful protests that are essential freedoms for all workers,” Michael Page, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch, said in 2018.

A group of workers at the Haft Tappeh sugar mill in #Iran have sent a letter to the @ilo detailing the way Iranian security forces' have been suppressing their protests for unpaid wages, including by threatening their families https://t.co/CrKrJK6C8f. pic.twitter.com/BA43mU5YxX

— IranHumanRights.org (@ICHRI) June 10, 2019

In May 2020, a court reportedly accused Omid Assadbeigi, the Haft Tappeh CEO, of bribing the provincial governor’s wife. He allegedly paid her $200,000 in cash through an intermediary and paid $25,000 toward the cost of her travel abroad. Assadbeigi was also accused of currency smuggling and misusing cheap foreign currencies allotted to businesses by the government.

Ethnic and Political Issues

Khuzestan’s Arabs have long complained of underrepresentation in local and national government. In November 2006, the judiciary banned the only ethnic Arab party, Lejnat al Wefaq (Committee of Reconciliation). The group is “focused on opposing the Islamic Republic of Iran and instigating unrest and tension among Arabs and non-Arabs,” the Ahvaz prosecutor’s office alleged in a statement. The group, founded in 1999, had previously won a seat in parliament in 2000 and all but one of the seats on the Ahwaz municipal council in 2003.

“Khuzestan has never had a strong presence in the echelons of power,” Reza Saeedi, a local agricultural specialist, told The Guardian in 2015. “We have no influential ministers, deputies, especially none who cares or has the political capital to take a stand against what is happening here.” The redirection of water from Khuzestan to other provinces – including Isfahan, Kerman and Yazd – reflects how politicians, clerics and businessmen from those areas form much of Iran’s elite. “Water flows towards power,” Michel said.

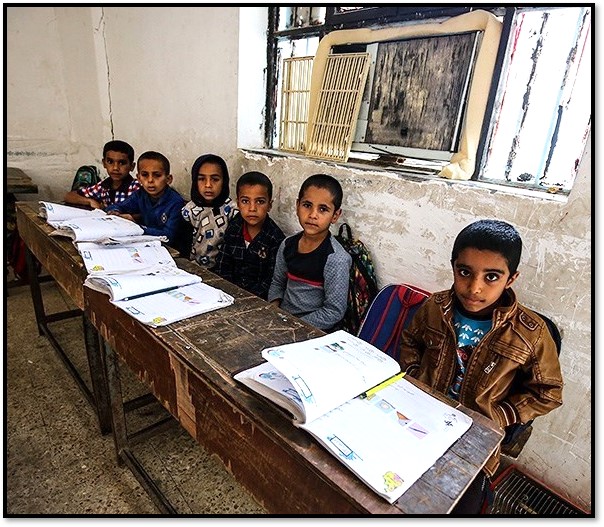

Ethnic tensions between Khuzestan’s Arabs and the central government have deepened discontent. “Concentrated in poor urban outskirts lacking in basic facilities, many Iranian Arabs have alleged that the government systematically discriminates against them, particularly in employment, housing, access to political office, and the exercise of cultural, civil and political rights,” Amnesty International reported in 2015. “The inability to use their mother language as a medium of instruction for primary education is also a source of deep resentment and frustration.”

In 2017, the Ahwaz Human Rights Organization claimed that Arabs held less than one percent of government and private sector managerial positions in Khuzestan. Since 1979, none of Khuzestan’s governors have been Arab—except for one who held the position for 45 days in 1990. On April 8, 2019, a video of Khuzestan Governor Ghlomareza Shariati dismissing the concerns of an Arab man impacted by massive floods was widely circulated on social media. “You won’t help us because we are Arab,” the man told the governor. “We have nothing left. Why do you help Syria but not us?” Shariati called the man “opponent of the state” and ordered him to leave.

Unrest

Khuzestan and other provinces with large minority populations have been “hotbeds of unrest due to the decades-long accumulation of grievances passed from generation to generation,” according to Ghaemi.

Major instances of unrest include:

- 2005 April Uprising – On April 15, Arabs in Ahvaz protested a leaked memorandum allegedly written by an advisor to President Mohammad Khatami that included proposals for resettling Arabs outside of Khuzestan and bringing non-Arabs to the province. The government said that the letter was a forgery, but clashes with security forces turned violent and demonstrations spread quickly across the province. The unrest lasted for four days and left least 50 people dead. After the crackdown, Ahwazi militants allegedly carried bombings in Tehran and Khuzestan in June and October 2005 and in January 2006.

- 2011 Ahvaz Day of Rage – Activists protested to mark the anniversary of the 2005 uprising. The government began arresting activists in the week prior to the anniversary. Security forces killed dozens and arrested many during the protests on April 15, according to Human Rights Watch.

- 2015 Protests – Dozens of Ahwazis were arrested before, during and after largely peaceful demonstrations to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the 2005 uprising.

- December 2017/January 2018 protests - On December 28, 2017, protests broke out in Mashhad, Iran’s second largest city, over economic hardships, corruption, and rising food and fuel prices. The initial protests were reportedly sparked by increases of up to 40 percent in staples, including eggs and poultry. They quickly morphed into anti-government demonstrations that spread to more than 80 cities, including at least six in Khuzestan. Demonstrations and clashes with riot police were particularly intense in the province. The protests waned by January 6. At least 20 people were killed and more than 3,000 arrested nationwide. The demonstrations were the largest challenge to the government since the 2009 Green Movement.

- 2018 Uprising of Dignity – On March 22, state-run television aired a children’s program that highlighted Iran’s ethnic diversity yet excluded Arab traditional clothing from dolls representing Khuzestan. All the other dolls wore ethnic costumes. The perceived insult triggered protests in Ahvaz and other cities that continued for more than a week. Hundreds were arrested.

- November 2019 protests –In a surprise overnight announcement on November 15, Iran hiked gas prices—by up to 300 percent—and introduced a new rationing system. The government’s goal was to raise funds to help the poor, but it backfired. Protests first broke out in Khuzestan. But they quickly spread to more than 100 towns and cities across Iran. More than 300 people were killed in clashes with security forces in less than week of protests. One of the worst massacres took place in Mahshahr, Khuzestan. Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps units killed as many as 148 people.

"Don't be afraid, we are all together," chant angry protesters facing riot police in Ahvaz, #Iran. The protests, confirmed by state news agencies, appear to have erupted after officials announced fuel price increases. #IranProtests pic.twitter.com/UbLBrrPSIP

— IranHumanRights.org (@ICHRI) November 15, 2019

Separatist Movements

Arab separatists have also launched sporadic attacks against the central government. During the first decade of the Islamic Republic, Ahwazis perpetrated several terrorist attacks, including a series of deadly bombings in 1979. In 1980, Arab separatists took 26 people hostage at the Iranian embassy in London. The six-day siege ended after the gunmen killed a hostage and threw his body out of a window. British special forces stormed the embassy and freed the hostages. One hostage and five of the six hostage-takers were killed.

Several Ahwazi separatist groups operate in Khuzestan and abroad. Groups that have called for an independent Arab state include The Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Ahwaz (ASMLA), the National Organization for the Liberation of Ahwaz (also known as Hazm), the Ahwazi Popular Democratic Front (APDF), and the Hawks of Ahwaz. The most prominent group is the ASMLA, which consists of two rival branches based in Copenhagen and The Hague, as well as the Mohiuddin Nasser Martyrs Brigade, a militia that operates in Khuzestan province. The ASMLA has claimed attacks on oil and gas installations, security forces and banks since 2005.

In September 2018, four gunmen killed 25 people at a military parade in Ahvaz. Both the Ahvaz National Resistance and ISIS claimed credit for the attack. Authorities arrested hundreds of people in the following weeks. “The timing suggests that the Iranian authorities are using the attack in Ahvaz as an excuse to lash out against members of the Ahwazi Arab ethnic minority, including civil society and political activists, in order to crush dissent in Khuzestan province,” Philip Luther, Amnesty International’s Research and Advocacy Director for the Middle East and North Africa, said in November.

In October 2020, opposition activist Habib Chaab was reportedly lured from his home in Sweden to Istanbul, where he disappeared. A Turkish official said that Iranian intelligence arranged for Chaab to be kidnapped and smuggled across the border to Iran. In November 2020, Iran’s intelligence ministry confirmed that Chaab was in custody and described him as the vice president of ASMLA. In a confession broadcast on state television, Chaab said that Saudi Arabia had given him funds to carry out operations in Iran. The ASMLA rejected the claim.

In January 2021, Iran executed Ali Mutairi, a 30-year-old champion boxer and sports coach, for allegedly killing two Basij militia members in 2018. He was also accused of being a member of ISIS. But human rights activists claimed that he and his two friends were tortured and forced to confess to the murders. Mutairi had reportedly been an advocate for Ahwazi rights and had been critical of the regime's policies. “We strongly condemn the series of executions, at least 28, since mid-December, including people from minority groups,” a U.N. spokeswoman said.

Authorities have been sensitive to any activities construed as promoting separatism. In February 2017, a 17-year-old Arab activist was arrested by the Intelligence Ministry. Officials asked him why he wore traditional Arab clothing and carried signs in Arabic to a rally about the drying of the Karoun river. In March 2018, a 15-year-old girl was arrested for writing poems that security forces alleged could incite violence. “Resist, my homeland, there is not much left of you,” she wrote. “Soon you will hear in your sky the sound of smiles and liberation’s call.”

Related Material: "Iran's Troubled Provinces - Baluchistan"

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of The Iran Primer at the U.S. Institute of Peace. Follow him @GarrettNada.