Nasser Hadian

Iran has turned the corner on Syria, its longstanding ally in the Arab world. It still wants close ties to a country that is the strategic center of the Arab world. But after three years of war, Tehran is also increasingly concerned that Syria may not hold together if President Bashar Assad stays in power because of bitter passions that now divide political factions, religious sects, ethnic groups and territory.

Iran has turned the corner on Syria, its longstanding ally in the Arab world. It still wants close ties to a country that is the strategic center of the Arab world. But after three years of war, Tehran is also increasingly concerned that Syria may not hold together if President Bashar Assad stays in power because of bitter passions that now divide political factions, religious sects, ethnic groups and territory. The Islamic Republic is now looking for an internationally negotiated solution with five goals: protection of minorities, credible democratic election, stability, containing jihadi militants and sectarianism, and an end to the killing. Tehran has not been willing to publicly embrace the Geneva I framework for negotiations, but it still would prefer to be part of the process. Iran believes it could play the kind of role it did during the 2001 Bonn talks on Afghanistan, when the Iranian delegation was pivotal in convincing the Afghan opposition to accept the U.S.-backed plan for a post-Taliban government. The key Iranian envoy then was Mohammad Javad Zarif, who is today Iran’s foreign minister. Tehran even feels some urgency in achieving a deal, for fear of the spillover of Syria’s instability on the wider Middle East.

The gradual shift in Iran’s position, especially notable since the mid-2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani, reflects regional, religious, sectarian and strategic considerations.

First, Iran does not really care that much about the Assad dynasty. Few inside the government support Assad on ideological grounds; the ruling Baath party is avowedly secular and socialist. Iran is more concerned about the alliance with the Syrian state, whoever is in power. At minimum, Iran wants a government in Damascus that is not hostile to Tehran. At maximum, it wants a regime that is shares Tehran’s strategic goals and interests.

First, Iran does not really care that much about the Assad dynasty. Few inside the government support Assad on ideological grounds; the ruling Baath party is avowedly secular and socialist. Iran is more concerned about the alliance with the Syrian state, whoever is in power. At minimum, Iran wants a government in Damascus that is not hostile to Tehran. At maximum, it wants a regime that is shares Tehran’s strategic goals and interests. Many in the Iranian leadership now believe that Syria cannot hold together as a stable and unified country as long as Assad is in power due to political and physical fragmentation. They fear three years of war have produced deep wounds that will not be healed as long as Assad is in power.

But Tehran also believes that the dismantlement of the entire regime—as happened in Iraq after the 2003 U.S. ouster of Saddam Hussein’s government, ruling Baath Party and military in Iraq—would be disastrous. It could produce a vacuum and potentially chaos, with even deeper spillover on the Middle East.

Second, Iran wants to protect Syrian territorial integrity. Syria’s fragmentation could endanger other countries, including neighboring Iraq. Over time, any attempt by Syria’s two million Kurds, who already operate in a semi-autonomous enclave, to break away could trigger aspirations for a wider Kurdish state cutting into other countries. And the breakup of the current Arab states would almost certainly produce wider insecurity across the region.

The spillover of Syria’s instability on Iraq and Lebanon are particularly worrisome for Iran. Tehran has important allies in both countries, and instability could weaken their position—and Iran’s influence. In Iraq, the government is has become an ally since Saddam Hussein’s ouster. And Lebanon is home to a large Shiite population with centuries-old Iranian ties.

Iran is also concerned about losing its strategic links to Hezbollah and Hamas, which have long run through Syria. Hezbollah is a Lebanese Shiite party and militia that Iran helped create in 1982 and has trained and armed ever since. And Hamas is a Palestinian party and militia that has been a key ally since shortly after it emerged in the late 1980s. Iran considers both parties to be forces for defense, deterrence, and retaliation in case of an Israeli or American attack on Iran.

Third, Iran fears the deepening politics of identity, including the politics of religious identity. Iran has supported revolutionary Islam, but among both Sunni and Shiite. Ironically, however, the world’s only modern theocracy is now concerned that the Syrian civil war will increase the sectarian divide between Sunni and Shiite across the region in ways that will hurt Iran—and Islam.

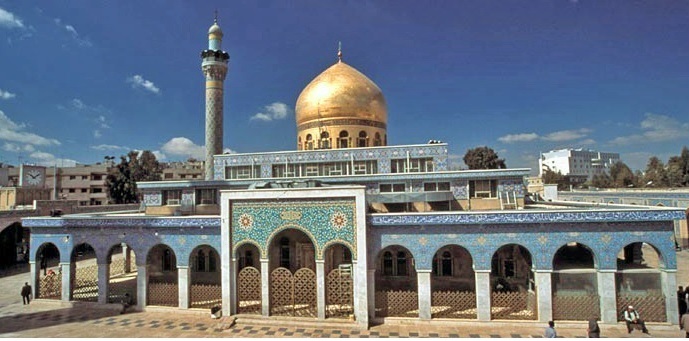

For centuries, Iranians have performed pilgrimages to dozens of Shiite holy places in Syria, like the Tomb of Zaynab on the outskirts of Damascus (above).

Sectarianism in the Islamic world, from North Africa across the Levant to the Gulf and south Asia, is already dangerous. It plays out among individuals, groups and nations. Iran’s Shiites, who are a minority among the world’s 1.6 Muslims, are concerned about the fate of Shiites in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

More broadly, Tehran is worried that the growth of religious identity will generate rivalries over their diverse absolute truths that could spark conflicts ultimately more violent and difficult to resolve. So Tehran has an interest in ending the Syrian conflict to extinguish the flames of sectarianism and prevent a deepening divide between Islam’s two major sects.

In the same vein, Iran wants protection of Syria’s minorities, including the Christians, Druze, Kurds and most of all the Alawites. The Alawites are widely associated with Shiism, even though many Shiites, including Iranians, do not view them as a legitimate offshoot. The real reason is that Syria’s minorities are potential allies, since they share a common concern about Sunnis who already dominate the Middle East physically, politically and numerically—and are now producing a growing number of extremist groups. The jihadis in Syria are also all Sunnis.

Fourth, Iran is increasingly concerned about the rising death toll—now estimated to total more than 130,000 from both sides—and the use of chemical weapons. Iran is sympathetic to the victims because of its experience, which included some 1 million casualties, from the eight year-war with Iraq in the 1980s. Iran was also the victim of the widest use of chemical weapons since World War I. Saddam Hussein’s regime repeatedly used mustard and nerve gas against Iran. Thousands are still dying from mustard gas today, more than a quarter century after the war ended.

Intense photo of fighting in Aleppo yesterday via @aleppomediacent http://t.co/gYuKs5EUWK h/t @DGisSERIOUS pic.twitter.com/L5t5NEQdbP

— Patrick Witty (@patrickwitty) January 5, 2014 Fifth, because of its isolation during war with Iraq, Tehran actually feels vulnerable—or strategically lonely. Iran was temporarily strengthened by the U.S. intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan, after the removal of its arch-enemies—Saddam Hussein in Baghdad in 2003 and the Taliban in Kabul in 2001. Over the next decade, Iran gained more leverage than at any point since the 1979 revolution.

But two factors have reversed the trend. As the West and key Arab governments grew concerned about a “Shiite Crescent” radiating from Tehran to Beirut, the United States offered even greater aid and more powerful arms to the Persian Gulf sheikhdoms, which are all committed to containing Iran. The U.S. drawdown of troops from both Iraq and Afghanistan also made Iran change its strategic calculation, with the rise of al Qaeda franchises among Sunnis along its borders and the potential return of Taliban political clout in Afghanistan.

Finally, Iran does not believe there is a viable military solution for Syria. A military victory by either side is neither possible nor desirable. Iran now favors an inclusive solution for all faiths and all political parties. It even favors a secular government that will include all minorities.

As a result, Iran believes the most viable solution is an election— organized and supervised by the international community—to choose the next government. It views an election as a means of conflict resolution as well as a means of selecting a new government.

Tehran has less faith that the Geneva peace talks will produce a solution for a simple reason: Neither side is now either willing or capable of genuine or enduring compromise. The opposition is too divided, while the most active fighters—the jihadist groups—are not in Geneva. They are likely to just keep fighting. And Assad is unlikely to simply quit or negotiate his own political suicide. So Iran believes the solution must be left to the Syria people in a popular vote.

Nasser Hadian is a professor of political science at the University of Tehran.

Photo credits: Leader.ir, Syria-Iran by RonenY [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons, Zaynab Tomb by Argooya at en.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org