Nasser Hadian

On the 35th anniversary of its revolution, Iran has found often novel compromises in blending Islam and modernity—politically, economically and socially. The government and most Iranians today share three goals: honoring the great Persian past and retaining an Islamic identity while also integrating more deeply into a globalizing world. The revolution today is all about synthesis. The struggle is finding the right balance.

On the 35th anniversary of its revolution, Iran has found often novel compromises in blending Islam and modernity—politically, economically and socially. The government and most Iranians today share three goals: honoring the great Persian past and retaining an Islamic identity while also integrating more deeply into a globalizing world. The revolution today is all about synthesis. The struggle is finding the right balance.Politics

Politically, Iran’s government borrows heavily from Western concepts, including separation of powers. Each branch has its own turf, to the point that they have the same kind of tensions that Western governments do—and sometimes even harsher. The parallel religious institutions—such as the Guardian Council—weigh in not to run daily government but as a fourth check on secular powers and politicians. Since 1988, Tehran has also added an Expediency Council of both religious and laymen to resolve political conflicts, another reflection of trying to negotiate a balance.

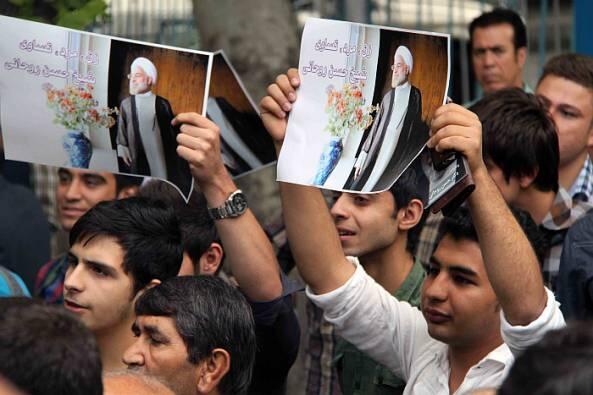

The revolution has brought a wide array of players into the political space over the past 35 years. Iran’s spectrum grows with every election, as new factions and faces join the fray. There are now dozens of parties, ranging from reformist to ultra-conservative, who compete passionately against each other. The diversity of opinion is even wider within society, ranging from more leftist to more rightist.

The idea of citizenry has also taken root in among Iran’s 80 million people, the majority of which has been born since the revolution and is highly educated. Voters have become more sophisticated in their demands. They are moving beyond passive obedience of either political or religious authority. People also have an impact on decisions, whether through the vote or street protests. So the government, for all its restrictions, has frequently been forced to accept public opinion, including electoral surprises.

The idea of citizenry has also taken root in among Iran’s 80 million people, the majority of which has been born since the revolution and is highly educated. Voters have become more sophisticated in their demands. They are moving beyond passive obedience of either political or religious authority. People also have an impact on decisions, whether through the vote or street protests. So the government, for all its restrictions, has frequently been forced to accept public opinion, including electoral surprises. But Iranian politics still have a wild side. Politics is controlled by a minority and the rules – or political red lines – shift from one presidency to the next and from one parliament to the next. Iran’s elections also involve a strange combination: Freedom to run is very limited—and candidates approved to run in one election can be disqualified when they try to run again. Competition is fierce. Yet results can be unpredictable.

Economics

Ironically, Iran has resolved the debate about an “Islamic economy.” After a lot of trial and error, Tehran opted to run the economy based largely on modern science and global standards rather than traditional religious practices. Aiding the oppressed is still a revolutionary tenet. But Iran has not become a socialist country. Modern economic principles, including respect for private property, have not been forfeited even as the government has tried to help the poor.

The fight is far from over, however. Iran does not have a corporate economy largely because the government-backed charities, or bonyads, control vast resources. Government institutions, such as the Revolutionary Guards, and quasi-government groups also control large chunks of economic life. So Iran does not have a large number of private companies, even though commerce has been one of the pillars of Iranian society for millennia.

The fight is far from over, however. Iran does not have a corporate economy largely because the government-backed charities, or bonyads, control vast resources. Government institutions, such as the Revolutionary Guards, and quasi-government groups also control large chunks of economic life. So Iran does not have a large number of private companies, even though commerce has been one of the pillars of Iranian society for millennia. The revolution has built infrastructure—such as roads, electricity, schools and some basic health services—particularly in small towns and rural areas. It paid off the shah’s foreign debt in the 1980s, revived the Stock Market in the 1990s, and has survived severe international sanctions, particularly since 2006. At great cost, Iran has also continued subsidies of basic commodities—from petroleum to basic foodstuffs.

But Iran’s economy has been plagued by gross mismanagement in recent years. Few in leadership positions have been willing to demonstrate the political courage to introduce the tough measures needed to turn the economy around, whether through more rigorous subsidy reforms, privatization or deficit reduction that would encourage local or foreign investment.

Iran is also still a rentier state disproportionately dependent on oil income. And the economy is highly vulnerable because Tehran has been unable to update its oil infrastructure since the revolution. After the latest U.S. sanctions were imposed in 2012, oil exports then dropped by more than half, while the value of Iran’s currency plummeted by sixty percent. Oil revenues have also not been distributed equitably or wisely, with corruption and favoritism now rampant. Privatization and deregulation have been largely unsuccessful because the government has allowed its assets to be transferred to favored “clients.”

Society

Iran initially tried to Islamicize society, but the forces of modernity have often prevailed. The Islamic Republic now openly tolerates scientific and even secular ideas. More than three decades after the revolution, Iranian society is arguably more modern than it was under the monarchy.

Changes in society are particularly evident among its youth and women. The Pahlavi monarchy may have been more progressive on women’s rights in the law, but the Islamic Republic has brought more women into education, the economy and politics, even though they have to comply with Islamic norms such as the dress code or strict family laws.

Changes in society are particularly evident among its youth and women. The Pahlavi monarchy may have been more progressive on women’s rights in the law, but the Islamic Republic has brought more women into education, the economy and politics, even though they have to comply with Islamic norms such as the dress code or strict family laws. Revolutionary Iran won a U.N. award for closing the gender gap in education. And the majority of students at Iranian universities are today female, despite recent restrictions on their coursework. Access to education and modern institutions has particularly brought many females from traditional families into the professions, politics and the arts.

The revolution has also adapted to the forces of globalization, as education, urbanization and technology, which have transformed society in ways that the government could not control. Demographics—particularly the baby boom generation born in the 1980s now coming of age—are a strong counterbalance to the aging revolutionaries.

But some sectors of society—the poor, the rural and women—clearly face serious inequities in politics and in life. The Islamic Republic is still patriarchal. Men dominate power and commerce. The poor and the rural have limited means of bettering their circumstances. And despite the pressures of globalization, the government controls freedom of speech and access to the outside world, although not completely.

But, ironically, on its 35th anniversary, a religious government has produced one of the most secular societies in the Middle East. Indeed, for many living in the Islamic Republic today, the relationship between the individual and God is private, not political.

Nasser Hadian is a professor of political science at the University of Tehran.

Photo credits: @HassanRouhani via Twitter, Iran oil exports via U.S. Energy Information Administration, Isfahan University graduates by gire_3pich2005 (Own work) [FAL] via Wikimedia Commons,

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org