Reza H. Akbari is a MENA Program Manager at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting and a doctoral student at American University, where he focuses on the history of the modern Middle East. Follow him on Twitter @rezahakbari.

Iran’s new president, Ebrahim Raisi, has had little experience in foreign policy. What do his statements suggest about his approach and agenda?

Ebrahim Raisi took office in August with practically no foreign policy experience. A quick look at his resume suggests that he may be more comfortable in a courtroom than representing Iran on the world stage. In 1981, at age 20, he started his career as a prosecutor for the city of Karaj. During the next four decades, Raisi climbed the ranks mainly within the judicial branch. His educational background is in Islamic jurisprudence and civil law. Raisi’s lack of foreign policy and executive experience will increase his reliance on Iran’s intricate bureaucracy, various power centers, and career diplomats to shape and execute foreign policy.

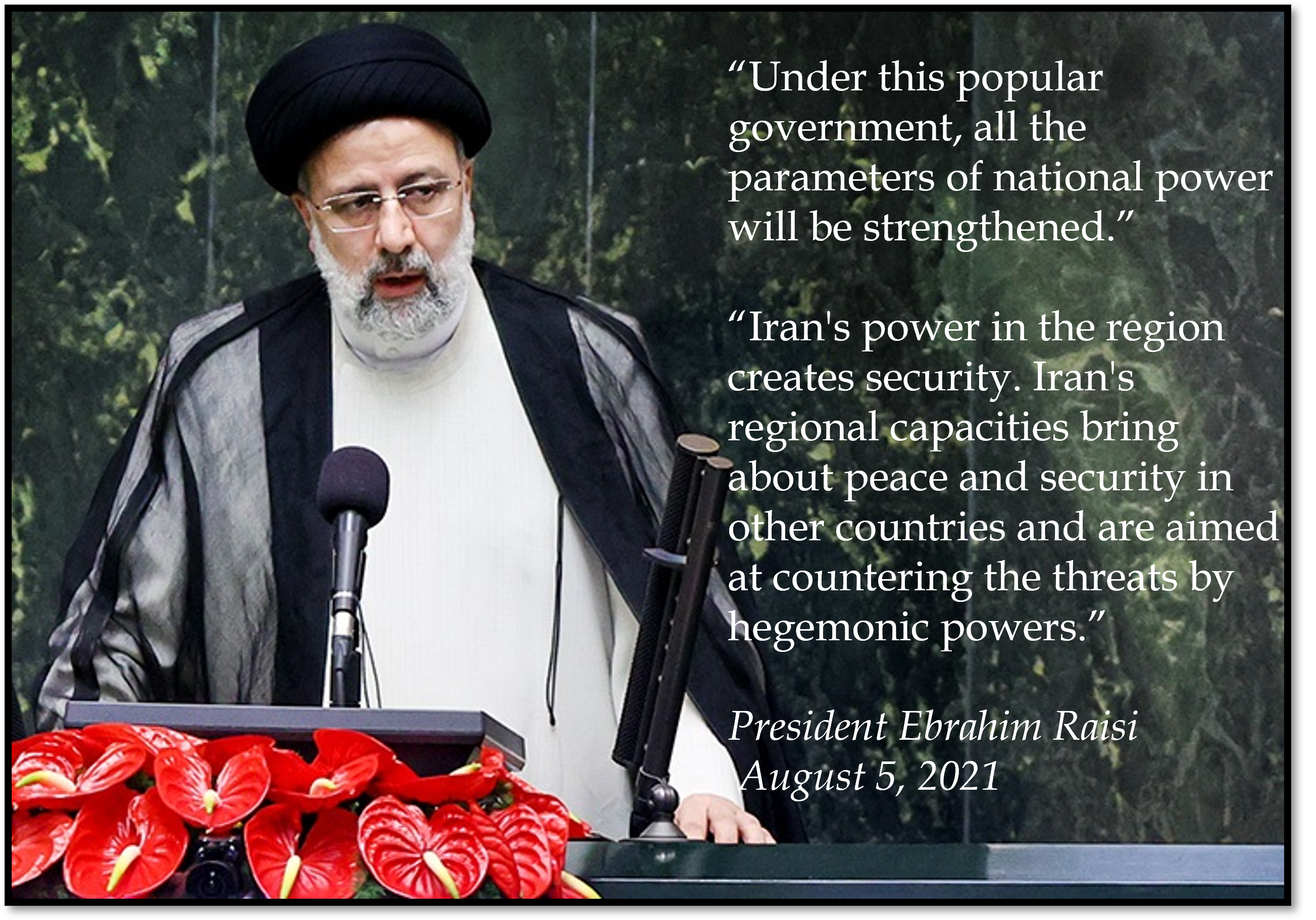

Raisi provided few specifics about his foreign policy agenda during his swearing-in ceremony in Parliament on August 5. He simply repeated longstanding positions of the Islamic Republic. He prioritized improving relations with neighbors and reiterated that foreign intervention in the region “resolves no problem.” Raisi also vowed that sanctions and pressure by the United States and Western powers will not deter Iran from developing its nuclear program.

Raisi provided few specifics about his foreign policy agenda during his swearing-in ceremony in Parliament on August 5. He simply repeated longstanding positions of the Islamic Republic. He prioritized improving relations with neighbors and reiterated that foreign intervention in the region “resolves no problem.” Raisi also vowed that sanctions and pressure by the United States and Western powers will not deter Iran from developing its nuclear program.

Raisi has indicated support for talks on returning U.S. and Iranian compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). But he has warned that Iran expects tangible results and will not allow negotiations to drag out.

Raisi, like his predecessor Hassan Rouhani, has demanded that the United States lift sanctions on Iran and return to the agreement. Raisi’s team, however, may be more guarded and strongheaded, especially on sanctions relief and willingness to negotiate on issues beyond the JCPOA. “Regional issues or the missile issue are non-negotiable,” Raisi said on June 21 during his first press conference as president-elect. The United States and European powers “have not been committed to something that was negotiated, agreed and signed as an accord. How is it that they want to negotiate new issues?”

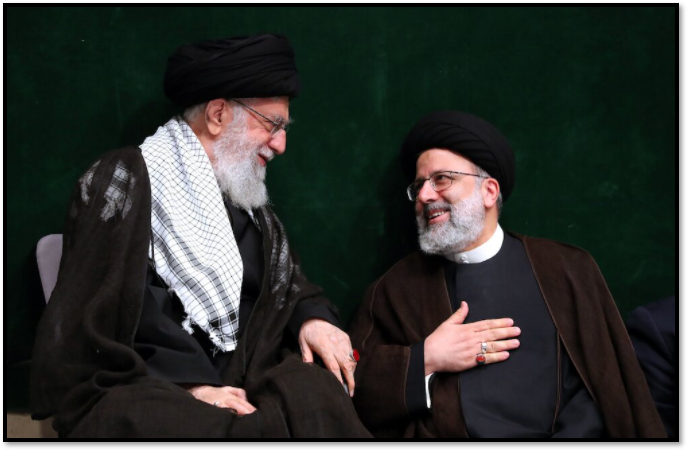

Raisi’s statements on the nuclear deal—and foreign policy more broadly—reflect a distrust of the West that he shares with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. On July 28, during Rouhani’s last full week in office, Khamenei told government officials, “It became clear in this administration that trusting the West will not work, as they are not going to help us, and they will strike a blow whenever they can.” Raisi, who is very loyal to Khamenei, will almost certainly heed that lesson.

Raisi’s foreign policy agenda, published during his campaign, stated that his approach will be based on the Supreme Leader’s three pillars of “security from the position of strength,” “peace from the position of power,” and “negotiation and diplomacy from the position of honor and interests.”

Under Iran’s constitution, where ultimate power rests with the Supreme Leader, what role does the president play in forming and executing foreign policy? How much latitude does Raisi have to shift policy?

Foreign policymaking in Iran is convoluted and messy. Several institutions and formal bodies as well as unofficial powerbrokers are involved. Foreign policy is not under the exclusive purview of the president, but he plays a crucial role in turning the broad strokes usually shaped by the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) and approved by the Supreme Leader into tangible action items.

The revised 1989 constitution charges the president with appointing and dismissing the foreign minister, who must be confirmed by Parliament. This process is often informally guided by the Office of the Supreme Leader, but the names come from the president.

The president also chairs the highly influential SNSC, which coordinates all governmental activities related to issues involving defense, intelligence services, and foreign policy. The council has 12 permanent members, including three military commanders, the heads of the judiciary and legislature, three cabinet ministers, two representatives of the Supreme Leader and the director of the planning and budget organization. An additional floating member is also added who is a minister appropriate to the topic of the debate. So, the president undoubtedly plays a role, but his power is limited by other players at the table.

What other officials and institutions are involved in foreign policy—either formally or informally? Who holds the greatest sway?

Iran is ruled by an autocratic form of government, but that does not mean that the Supreme Leader simply issues decrees, and everyone falls in line. In developing policy, an often-long process of consensus-building happens within a maze of entities and power structures. Ideological factions are seldom in agreement on any issue, including foreign policy, which adds another layer of political intrigue. The political environment is highly contested, and alliances shift constantly. Personal and institutional rivalries play a huge role as well. The institutional power of various entities also changes based on the individual in charge, so determining who holds the greatest sway is not a simple calculation.

Officially speaking, the SNSC and the Office of the Supreme Leader play the most important and direct role in steering foreign policy. SNSC decisions must be approved by the Supreme Leader, but he does not directly take part in the body’s deliberations. Given the sensitive nature of the topics discussed, the SNSC’s proceedings happen behind closed doors. But the media is quick to report on the outputs and at times the disagreements between the various individuals at the table.

Three governing bodies play an indirect yet important role in steering foreign policy. Parliament, or the Majles, must approve all international agreements and treaties. It has the power to pass laws, which then must be implemented by the executive branch.

For example, the Majles passed a law in December 2020 that required the government to ramp up its nuclear program. It also obligated the government to curtail international inspectors’ access to nuclear sites if U.S. sanctions on Iran’s banking and oil sectors were not lifted within two months. The Rouhani government opposed the bill but had to implement it.

The floor of the Majles is also a scene of frequent clashes between various political factions and the government over foreign policy issues. For example, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif was required to keep lawmakers informed about the nuclear talks between Iran and the world’s six major powers. Zarif’s briefing at the Majles on May 24, 2015 ended in a verbal altercation with a hardliner who called him a traitor for making too many concessions to Western powers.

All laws passed by the Majles are subject to approval by the powerful Guardian Council, which provides the body with an indirect role in shaping foreign policy. The Council consists of 12 men—half of them clerics appointed by the Supreme Leader and the other half lawyers chosen by the Majles based on the recommendations of the head of the judicial branch. This supervisory role has led to gridlocks, especially when Parliament has been led by reformists.

In case of a stalemate between the Majles and the Guardian Council, the constitution charges the Expediency Council with breaking the impasse. If the Supreme Leader cannot resolve a dispute through traditional mechanisms, he may act only after consulting the Expediency Council, according to Articles 110 and 112. The body consists of 44 members who belong to various ideological currents and a guest who is invited based on topic of deliberation. The members are chosen every five years by the Supreme Leader. The power of the Expediency Council has significantly waned since Khamenei became the Supreme Leader in 1989. He has seldom approached the body for guidance.

Thousands of government employees and career diplomats also inform the policymaking process. They provide senior political appointees with direction and pass on institutional memory and organizational culture to the next generation. The president—no matter how radical—must contend with an existing set of norms protected by technocrats.

Presidents have historically selected their cabinet ministers from the available pool of technocrats, many of whom have loyalties to the institutions they have served. Raisi’s foreign minister, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, reflects this phenomenon. The conservative-leaning diplomat reportedly has close ties to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), but his long tenure at the foreign ministry (1997 to 2016) demonstrates that his national security orientation trumps any fixed political alliances. He served in senior roles under three different presidents, reformist Mohammad Khatami, hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and centrist Hassan Rouhani.

In April 2021, a leaked interview with Foreign Minister Zarif caused a political firestorm because he faulted the IRGC's elite Qods Force for sidelining the foreign ministry. What did the three-hour audio clip reveal about the IRGC's role in foreign policy?

The leaked interview exposed the depth of the rivalry between the foreign ministry and the IRGC in clear terms. “In the Islamic Republic the military field rules,” Zarif said. He recounted how he often had to yield to the preferences of Qassem Soleimani, the former commander of the IRGC’s elite Qods Force who was killed in a U.S. drone strike in 2020. “Every time I went to negotiate, Commander Soleimani would tell me to request this and that,” Zarif said.

Zarif criticized the IRGC for allowing Russia to fly its military planes over Iran to bomb targets in Syria and for using civilian Iran Air flights to move military equipment and personnel to Syria. He, however, acknowledged coordinating closely with Soleimani on some issues. For example, the two had productive exchanges in the prelude to the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

But overall, Zarif painted Soleimani and by extension the IRGC as an entity that often failed to communicate its actions with other decision-making bodies in a consistent and transparent manner. This created confusion and led to contradictory messaging.

How are portfolios divided among the foreign ministry, the IRGC and other institutions? Who takes the lead on which issues?

The IRGC has been the dominant player on regional security issues, such as Iran’s involvement in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen. And the foreign ministry has taken the lead on international trade negotiations, cultural exchanges, and other non-military matters. But the division of portfolios is not formalized or necessarily clear. Military commanders and diplomats need to cooperate to implement foreign policy as outlined by the SNSC and approved by the Supreme Leader.

The IRGC has been the dominant player on regional security issues, such as Iran’s involvement in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen. And the foreign ministry has taken the lead on international trade negotiations, cultural exchanges, and other non-military matters. But the division of portfolios is not formalized or necessarily clear. Military commanders and diplomats need to cooperate to implement foreign policy as outlined by the SNSC and approved by the Supreme Leader.

What are the pillars of Iran’s foreign policy as defined in the constitution? In what ways has Iran’s policy adhered to the constitution?

Articles 152, 153, and 154 of the constitution outline Iran’s foreign policy. The Islamic Republic aims to reject all types of hegemonic domination while protecting its territorial integrity. True to the revolutionary slogan of “neither East, nor West,” Iran is to pursue nonalignment, while protecting its natural resources (mainly oil and gas) from any external control. Lastly, the constitution prohibits the country from interfering in the internal affairs of other nations, but it supports the idea of protecting the “oppressed” from the “oppressors” around the globe.

The three broad articles leave plenty of room for paradoxical behavior and justification for inconsistent actions. For example, Iran’s support for Palestinian militant groups, including Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, is rhetorically justified by the political elite as a decision to protect the “oppressed” people of Palestine. This aligns well with the professed objectives of Article 154 of the constitution.

The Islamic Republic is relatively silent, however, on China’s persecution of the Muslim Uyghur population. Iran appears to be prioritizing strong economic ties with China, its largest trade partner, over defending the Muslim minority.

Iran’s 25-year cooperation agreement with China, signed in March 2021, appears to contradict Article 152, which says that Iran is to remain free from hegemonic domination. The pact is intended to significantly boost Tehran’s economic and military ties with the Asian power. Decades of isolation and sanctions imposed by the West have pushed Iran to look East for investments in key sectors, including energy, banking, telecommunications, infrastructure, and health care.

The details of the deal with China were not publicized, but Iranian opposition figures accused the government of compromising the country’s political sovereignty while risking its natural resources. Article 153 explicitly forbids any agreement resulting in foreign control of natural resources.

Officials rejected the accusations and described the agreement major diplomatic achievement. They tried to convince the public that the pact did not open Iran to domination by China. The government often provides justifications for its foreign policy using language that aligns with the constitution.