Since the early 2000s, Iran has supplied cruise and ballistic missiles to its proxies in at least three countries—Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen. Tehran’s transfer of missiles—which range from 120 km to 1,200 km, or 77 miles to 745 miles—allows its proxies to hit targets at further range and with greater precision than either artillery or unguided rockets. Iran’s missile exports serve three purposes: They strengthen Iran’s proxies. They develop more military options for Iran and its allies. And the deployment of missiles under Iran’s direct or indirect control would allow it to strike any adversary during a conflict from multiple directions. The Islamic Republic, in turn, has gained leverage with both regional and international players by building up the military capacity of its regional proxies.

Since the early 2000s, Iran has supplied cruise and ballistic missiles to its proxies in at least three countries—Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen. Tehran’s transfer of missiles—which range from 120 km to 1,200 km, or 77 miles to 745 miles—allows its proxies to hit targets at further range and with greater precision than either artillery or unguided rockets. Iran’s missile exports serve three purposes: They strengthen Iran’s proxies. They develop more military options for Iran and its allies. And the deployment of missiles under Iran’s direct or indirect control would allow it to strike any adversary during a conflict from multiple directions. The Islamic Republic, in turn, has gained leverage with both regional and international players by building up the military capacity of its regional proxies.

Iran’s missile program, which dates back to the monarchy and briefly included collaboration with Israel, has been an increasingly important military staple since the 1979 revolution, as the Islamic Republic’s warplanes became obsolete. In the mid-1980s, Tehran acquired Scud missiles from Libya, Syria and North Korea and also began adapting the technology for their missile variants. Since the late 1980s, Iran has developed an increasingly sophisticated arsenal of missiles—with growing range and accuracy—that became critical to its offensive capabilities as well as its strategy of defensive deterrence.

Related Material:

- Iran's Missiles: Evolution and Arsenal

- Iran's Missiles: Military Strategy

- Iran's Missiles: Infographics and Photos

- Iran's Missiles: Timeline of Attacks

Iran’s missile transfers have varied in quantity and range. As of February 2021, ballistic missiles had been used in only one of the three countries.

- Lebanon: Iran has transferred the largest number of missiles—estimated to total 14,000, with ranges of 125 km to 300 km, or 77 miles to 185 miles—to Hezbollah, the largest militia and a political powerbroker in Lebanon. In the early 2000s, Hezbollah was the first recipient of Iranian missiles. Since 2016, Iran has reportedly provided conversion kits to upgrade Hezbollah’s arsenal from short-range rockets to precision-guided missiles capable of hitting deep into Israel. Hezbollah has fired thousands of rockets into Israel, but it had not yet unleashed ballistic missiles across the border as of February 2021.

- Yemen: Since 2016, Tehran has reportedly transferred medium-range missiles—with ranges up to 1,200 km—to Houthi rebels fighting a civil war and a military campaign led by Saudi Arabia. Iran has also smuggled short-range ballistic missiles—with ranges of 250 km and 1,000 km, or 150 miles to 620 miles—to the rebels, who are Zaydi Shiites. In response to Saudi airstrikes, the Houthis have launched dozens of these missiles against major Saudi cities.

- Iraq: Since 2018, Iran has reportedly supplied short-range ballistic missiles – with ranges up to 700 km – to Shiite militias in Iraq, including Kataib Hezbollah and Saraya al Jihad. The missiles could hit U.S. forces based in Iraq and even reach Israel, if launched from the western desert. But ballistic missiles had not been used against either domestic or regional rivals as of February 2021.

The following is a detailed rundown of the cruise and ballistic missiles that Iran has transferred to allies and the U.S. and U.N. response.

Hezbollah (Lebanon)

As of mid-2020, Hezbollah had an estimated 14,000 short-range projectiles, the deadliest part of its arsenal of 130,000 to 150,000 rockets and missiles. (Most of its arsenal consisted of unguided artillery rockets, also supplied by Iran). Hezbollah has three types of short-range missiles capable of reaching Tel Aviv, the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) reported in July 2018.

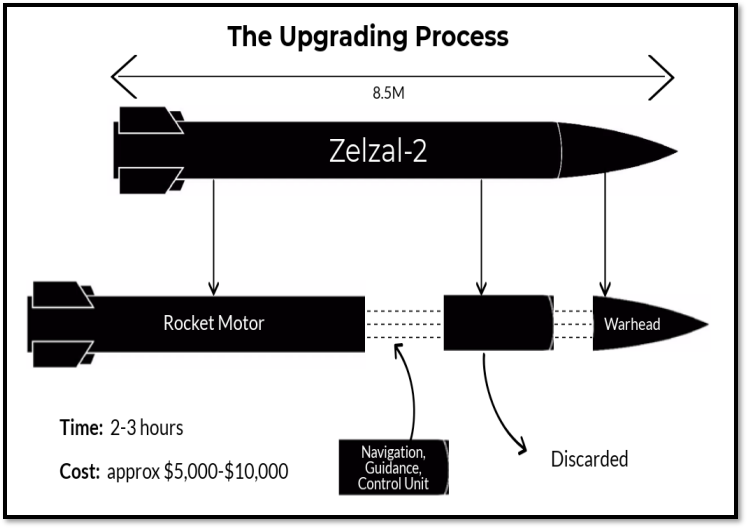

- The Zelzal-1, an unguided rocket with a range of 125 to 160 km (or 77 to 100 miles)

- The Zelzal-2, an unguided rocket with a range of 210 km (or 130 miles)

- The Fateh-110, a ballistic missile which has a range of 250 to 300 km (or 155 to 185 miles)

As of February 2021, Hezbollah had not acquired missiles with a longer range than the Fateh-110, although there were unconfirmed reports that Syria transferred Scud rockets to Hezbollah in 2010. Between 2013 and 2015, the Revolutionary Guards allegedly tried to transport ballistic missiles with greater precision to Lebanon via Syria. Israel claimed that its airstrikes had destroyed most shipments. “Should Hezbollah acquire precision-guided missiles, they would have the ability to directly target Israeli civilians, towns and cities, and even national strategic assets,” the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) said in 2019.

In September 2018, Israel accused the Revolutionary Guards of supplying Hezbollah with the kits. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu presented evidence that Hezbollah had allegedly set up three missile conversion plants near Beirut International Airport with Iranian help. “Hezbollah is deliberately using the innocent people of Beirut as human shields,” Netanyahu told the U.N. General Assembly. In August 2019, the IDF claimed that four senior Iranian and Hezbollah officials were involved in the project. It also identified a missile conversion plant in southern Lebanon.

The Houthis (Yemen)

- The Quds-1, a cruise missile with a range of 700 to 800 km (or 435 miles to 500 miles)

- The Qiam-1, a ballistic missile with a range of 700 to 800 km (or 435 miles to 500 miles)

- The Burkan-1, a ballistic missile with a range of 800 km (or 500 miles)

- The Burkan-2H, a ballistic missile with a range of 1,000 km (or 620 miles)

- The Burkan-3, a ballistic missile with a range of 1,200 km (or 745 miles)

The Houthis have been the only Iranian proxy to use a medium-range ballistic missile (a missile with a range greater than 1,000 km) in combat as of February 2021. They mainly targeted Saudi military installations, including the Ministry of Defense in Riyadh, a Red Sea base, and a civilian airport in southwest Saudi Arabia. In the first five years of the war, Houthi missile attacks killed more than 400 military personnel in the Saudi-led coalition, CSIS reported.

The Houthis claimed local production of their ballistic missiles without foreign help, but American and Israeli missile experts were skeptical. “The Burkans look like Scud derivatives, so they must have originated in a Scud derivative-producing country,” Israeli analyst Uzi Rubin wrote in 2017. “There are only two such countries today: North Korea and Iran.” The Burkan-2H features a nose cone common on Iranian ballistic missiles, Rubin also noted.

A U.N. investigation concluded that Iran had manufactured the missiles and smuggled them into Yemen. “Many of the internal design features, external characteristics and dimensions of the remnants of the missile inspected by the Panel are consistent with those of the Iranian designed and manufactured Qiam-1 missile,” U.N. experts reported in January 2018. “This means that they were almost certainly produced by the same manufacturer.”

In November 2018, U.S. Special Representative on Iran Brian Hook unveiled parts of a surface-to-air missile with Farsi markings interdicted en route to Yemen by the Saudi military. “The conspicuous Farsi markings is Iran’s way of saying they don’t mind being caught violating U.N. resolutions,” Hook said.

Kataib Hezbollah and Saraya al Jihad (Iraq)

As of late-2020, at least two Shiite militias in Iraq—Kataib Hezbollah and Saraya al Jihad—had tens of short-range ballistic missiles reportedly provided by Iran. Both had ranges that could threaten U.S. forces in Iraq, Arab allies and Israel:

- The Fateh-110, a ballistic missile with a range of 250 km to 300 km (or 155 miles to 185 miles)

- The Zolfaghar, a ballistic missile with a range of 700 km (or 435 miles)

Kataib Hezbollah maintained operational control over the missiles, most kept in southern Iraq, while Saraya al Jihad helped the Revolutionary Guards transport them from Iran. “Missiles and larger rockets are now moved from Iran into Iraq in parts, where possible broken down into warhead, fuel, and body, which allows smaller and less conspicuous vehicles (like water or oil tankers) and smaller shipping containers to be used,” Knights wrote in October 2020.

As of February 2021, Kataib Hezbollah had not fired its ballistic missiles on U.S. forces or at Israel, although it was allegedly responsible for several Katyusha rocket attacks near U.S. bases and diplomatic facilities. The ballistic missiles were sent to Iraq as a “backup plan” if the United States attacked Iran, a senior Iranian official told Reuters. “The number of missiles is not high, just a couple of dozen, but it can be increased if necessary,” he said. In 2018, Iran also began training Shiite militias to produce ballistic missiles locally. The militias allegedly set up missile factories in al Zafraniya, east of Baghdad, and Jurf al Sakhar, north of Karbala.

In September 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that he was “deeply concerned” about reports of ballistic missile transfers. “If true, this would be a gross violation of Iraqi sovereignty,” he tweeted. “Baghdad should determine what happens in Iraq, not Tehran.” In December 2019, Congresswoman Elissa Slotkin, a former CIA specialist on Shiite militias, warned the Iraqi government that ballistic missiles launched by militias could jeopardize the U.S. military mission in Iraq. “People are not paying enough attention to the fact that ballistic missiles in the last year have been placed in Iraq by Iran with the ability to project violence on the region,” she said. Between 2018 and 2021, U.S. forces in Iraq were repeatedly targeted by short-range rocket attacks, but Iraqi militias had not fired missiles on American forces.

Deeply concerned about reports of #Iran transferring ballistic missiles into Iraq. If true, this would be a gross violation of Iraqi sovereignty and of UNSCR 2231. Baghdad should determine what happens in Iraq, not Tehran.

— Secretary Pompeo (@SecPompeo) September 1, 2018

In 2019, Israel reportedly conducted seven airstrikes against Iraqi missile depots and military convoys in Iraq to preemptively destroy Iranian missiles. Prime Minister Netanyahu confirmed that Israel had taken action, but he did not comment on specific airstrikes. “We are working against Iranian consolidation—in Iraq as well,” Netanyahu told Israel’s Channel 9 News in August 2019.

U.S. and U.N. Response

Since 2005, both Republican and Democratic administrations have sanctioned Iran for its ballistic missile program. President George W. Bush first sanctioned three Iranian military industries –the Aerospace Industries Organization, the Shahid Hemmat Industrial Group and the Shahid Bagheri Industrial Group--for their role in supporting Iran’s missile production. In 2008, the Bush administration sanctioned the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lanes (IRISL), the national shipping company, for transferring missile components.

In 2010, President Barack Obama imposed sanctions on the IRGC Air Force and the IRGC Missile Command, the two military units in charge of Iran’s ballistic missiles. The administration did not lift sanctions on Iran’s ballistic missile program after it signed the 2015 nuclear deal. In January 2016, the Treasury designated five Iranians who had procured ballistic missile components from abroad.

The Trump administration expanded U.S. sanctions to include Iran’s transfer of missiles to proxies. In May 2018, the Treasury sanctioned members of the Revolutionary Guards charged with providing ballistic missile-related technology to the Houthis. It also imposed sanctions on foreign companies based in Russia, China and the United Arab Emirates that supported Iran’s ballistic missile program.

The United Nations also condemned Iran’s missile transfers to proxies. In 2010, Security Council Resolution 1929 sanctioned Iran’s entire missile industry. It also banned Iran from selling or transferring ballistic missiles to any other nation and forbid all countries from selling missile technology to Iran. The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, brokered by the world’s six major powers, extended those prohibitions until October 2023. But Iran has reportedly violated those prohibitions by providing missiles to Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen.

Timeline: U.S. Sanctions on Iranian Missiles

2000

March 14: The Iran Nonproliferation Act authorized the United States to sanction individuals and organizations providing material aid to Iran’s nuclear, chemical, biological and ballistic missile weapons programs

2005

June 28: Executive Order 13382 sanctioned the Aerospace Industries Organization (AIO), Shahid Hemmat Industrial Group, Shahid Bagheri Industrial Group for involvement in Iran's ballistic missile development.

2006

July 18: Executive Order 13382 sanctioned Sanam Industrial Group, a subordinate of Aerospace Industries Organization (AIO), for purchasing millions of dollars of equipment from entities associated with missile proliferation. The sanctions also targeted Ya Mahdi Industries Group, a subordinate of Iran’s AIO, for making international purchases of missile-related technology and goods for Iran.

2007

Jan. 9: The U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Iranian state-owned financial institution Bank Sepah for its support of missile proliferation. Treasury Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Stuart Levey said that “Bank Sepah is the financial linchpin of Iran's missile procurement network and has actively assisted Iran's pursuit of missiles capable of carrying weapons of mass destruction.”

March 30: Executive Order 13382 designated Defense Industries Organization (DIO), an entity controlled by Iran's Ministry of Defense Armed Forces Logistics and involved in Iran’s nuclear and missiles programs.

Oct. 25: Executive Order 13382 sanctioned Iran’s largest bank, Bank Melli Iran, for providing services to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and Qods Force which were involved in nuclear and ballistic missile programs. The order also directly sanctioned the IRGC.

2008

July 8: Executive Order 13382 designated Shahid Sattari Industries for its manufacturing and maintaining of ground support equipment for Shahid Bagheri Industries Group (SBIG). SBIG was designated on June 28, 2005 for its role in Iran’s missile program. The order also included measures against Moshen Hojati who was affiliated with Aerospace Industries Organization (AIO) which managed Iran's missile program, Naser Maleki who oversaw work on the Shahab-3 ballistic missile program and headed Shahid Hemmat Industrial Group (SHIG). SHIG was designated on June 28, 2005 for its role in Iran’s ballistic missile program.

Sept. 10: Executive Order 13382 sanctioned Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL), a state-owned shipping company, for transporting previously sanctioned missile-related and proliferation-related military cargo for Iran’s government.

2009

April 7: Executive Order 13382 sanctioned Niru Battery Manufacturing Company, a DIO subsidiary, for manufacturing power units for Iranian missile systems.

2010

June 16: Executive Order 13382 designated the IRGC Air Force in charge of deployment and operations of Iran’s ballistic missile program, the IRGC Missile Command in charge of deployment and operations of Iran’s ballistic missile program, and the Naval Defense Missile Industry Group owned or controlled by AIO.

2012

July 12: The U.S. Treasury Department designated an additional 11 entities and four individuals under E.O. 13382 to further disrupt Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs.

Dec. 21: The Treasury Department designated four companies and one individual pursuant to E.O. 13382, including SAD Import Export Company for sending weapons materials to Syria on behalf of DIO and Doostan International Company for providing services to AIO.

2013

Jan. 15: President Barack Obama signed the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act (IFCA) of 2012 into law. The act sanctioned Iranian economic sectors including dealings in precious metals used for missile, nuclear, or military programs

May 13: The U.S. Treasury Department designated 20 individuals and entities for involvement in Iran’s missile and nuclear proliferation networks. The Deputy Minister of Defense and Dean of Malek Ashtar University was among the designees for his significant contribution to Iran’s missile program.

2014

April 29: The U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned eight Chinese companies acting to proliferate ballistic missiles on behalf of Karl Lee, who was designated in April 2009.

2016

Jan. 17: The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated 11 entities and individuals based in the UAE and China involved in procuring materials for Iran’s ballistic missile program. Those sanctioned included Hossein Pournaghshband and his company Mabrooka Trading, Chen Mingfu, Candid General Trading, and more.

March 16: The U.S. Treasury Department’s OFAC sanctioned Shahid Nuri Industries and Shahid Movahed Industries, two subsidiaries of Shahid Hemmat Industrial Group (SHIG), for their contributions to Iran’s ballistic missile program.

2017

Feb. 3: The U.S. Treasury Department announced new sanctions on 13 individuals and 12 entities for supporting Iran’s ballistic missile program and its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The new sanctions came less than a week after Iran tested a medium-range ballistic missile. Washington condemned the launch and officially put Iran “on notice” on February 1.

March 21: The United States imposed sanctions on 11 entities and individuals for “transfers of sensitive items to Iran’s ballistic missile program.” The measures were part of a wider move under the Iran, North Korea, and Syria Nonproliferation Act.

May 17: The U.S. Treasury Department blacklisted three individuals and four entities, including a China-based network, for supporting Iran’s ballistic missile program. The Treasury worked in conjunction with the State Department, which released a semi-annual report to Congress on Iran’s human rights abuses.

July 18: The U.S. State Department announced new sanctions on “18 entities and individuals supporting Iran’s ballistic missile program and for supporting Iran’s military procurement or Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), as well as an Iran-based transnational criminal organization and associated persons.”

Aug. 2: President Trump signed a bipartisan bill called the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act. The bill directs the president to impose sanctions against Iran’s ballistic missile or WMD programs, the sale or transfer to Iran of military equipment or related technical or financial assistance, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Sept. 14: The U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned 11 entities and individuals for supporting Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps or networks responsible for cyber-attacks against the United States. “These sanctions target an Iranian company providing material support to the IRGC’s ballistic missile program, airlines that support the transport of fighters and weapons into Syria, and hackers who execute cyber-attacks on American financial institutions,” said Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin.

2018

Jan. 4: The U.S. Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned five Iran-based entities for ties to the country's ballistic missile program. The United States said the organizations were owned or controlled by an industrial firm responsible for developing and producing Iran's solid-propellant ballistic missiles. The sanctions froze any U.S. property the entities hold and prohibited Americans from engaging with them.

Jan. 12: Actions pursuant to Executive Order 13382 targeted proliferators of weapons of mass destruction and their supporters. Designations included Chinese-national Shi Yuhua for selling navigation equipment to Iran's Shiraz Electronics Industries and Pardazan System Namad Arman (PASNA) for providing goods and services to Iran’s Electronic Components Industries. Treasury Secretary Mnuchin said that the U.S. was “targeting Iran's ballistic missile program and destabilizing activities, which it continues to prioritize over the economic well-being of the Iranian people."

May 22: The U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned five Iranians for providing ballistic missile-related technical expertise or transferring weapons to the Houthis, a Zaydi Shiite movement that has been fighting Yemen’s Sunni-majority government since 2004. The five individuals were associated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Qods Force, an elite unit responsible for operations outside of Iran.

2019

Sept. 3: The United States imposed new sanctions on Iran’s Space Agency and two of its research institutes for supporting ballistic missile development. “Iran’s civilian space launch vehicle program allows it to gain experience with various technologies necessary for development of an ICBM – including staging, ignition of upper-stage engines, and control of a multiple-stage missile throughout flight,” warned the State Department.

Dec. 11: The U.S. Treasury sanctioned Iran’s largest shipping company, the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) and national airline, Mahan Air. It accused IRISL of using falsified documents and other deceptive tactics to secretly ship equipment for Iran’s Aerospace Industries Organization (AIO) and Shahid Hemmat Industries Group (SHIG)—entities that operate Iran’s ballistic missile program. Mahan Air allegedly helped Tehran transport missile-related graphite and high-grade carbon fiber in violation of U.N. sanctions.

2020

Jan 10: The Treasury Department also blacklisted eight senior Iranian officials, including the secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, Ali Shamkhani. “The United States is targeting senior Iranian officials for their involvement and complicity in Tuesday’s ballistic missile strikes,” said Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. Iran had launched more than a dozen missiles at two Iraqi bases housing U.S. troops in retaliation for the killing of Qassem Soleimani, the head of the elite Qods Force.

Feb. 25: The State Department announced sanctions on 13 foreign companies and individuals for supporting Iran's missile program. The entities were based in China, Iraq, Russia, and Turkey. The State Department said that the action was based on a periodic review required under the Iran, North Korea, and Syria Nonproliferation Act.

June 8: The United States expanded sanctions on Iran’s shipping industry. The Treasury Department designated Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) and its Shanghai-based subsidiary, E-Sail Shipping Company Ltd, along with more than 100 ships and tankers. “IRISL has repeatedly transported items related to Iran’s ballistic missile and military programs and is also a longstanding carrier of other proliferation-sensitive items,” including items that can be used in Iran’s nuclear program, Secretary Pompeo said.

July 30: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced a major expansion of State Department-administered Iran metals-related sanctions. Pompeo identified 22 specific materials used in connection with Iran’s nuclear, military, or ballistic missile programs and stated that those who knowingly transferred such materials to Iran were sanctionable pursuant Section 1245 of the Iranian Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act.

Sept. 21: The United States sanctioned 24 government organizations, companies, officials and suppliers connected to Iran’s conventional arms, nuclear and missile programs. The new sanctions targeted six individuals and four companies that supplied liquid fuel for ballistic missiles and space rockets.

Oct. 29: The State Department sanctioned six companies and two individuals based in China and Hong Kong for doing business with companies owned or controlled by IRISL. IRISL and its Shanghai-based subsidiary, E-Sail Shipping Company Ltd, had been sanctioned in June 2020 for transporting items related to Iran’s ballistic missile and military programs.

Nov. 25: The State Department sanctioned four companies located in China and Russia for supporting Iran’s missile program, under the Iran, North Korea, and Syrian Nonproliferation Act. Two of the companies—Chengdu Best Materials Co. Ltd. and Zibo Elim Trade Co., Ltd. —were located in China. Nilco Group and Joint Stock Company Elecon were located in Russia.

2021

Jan. 15: The United States sanctioned three weapons manufacturers, seven international shipping companies and two Iranian business executives for transferring arms to proxies in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and Yemen. “This military equipment, which includes attack boats, missiles, and combat drones, provides a means for the Iranian regime to perpetrate its global terror campaign,” Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said. The sanctions targeted three branches of Iran’s defense ministry: the Marine Industries Organization (MIO), Aerospace Industries Organization (AIO), and the Iran Aviation Industries Organization (IAIO) as well as Iranian, Chinese and Emirati businesses that did business with Iran’s national maritime shipping company, the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL).

Timeline: U.N. Sanctions on Iranian Missiles

2006

July 31: U.N. Security Council Resolution 1696 called on all Member States to “prevent the transfer of any items, materials, goods and technology that could contribute to Iran’s enrichment-related and reprocessing activities and ballistic missile programs.”

Dec. 23: U.N. Security Council Resolution 1737 directed all U.N. member states to adopt measures to prevent the supply, sale or transfer of materials to Iran that could be used for nuclear or ballistic missile programs. Among the individuals designated was General Yahya Rahim Safavi, then the Revolutionary Guards commander, for his alleged involvement in both Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs. Resolution 1737 also called on members to “exercise vigilance” to prevent individuals involved in Iran’s proliferation or missile programs from entering or transiting their territories.

2007

March 24: U.N. Security Council Resolution 1747 prohibited member states from procuring combat equipment or weapons systems from Iran and called on states to “exercise vigilance and restraint” in supplying such items to Iran. It also added the names of 18 individuals, companies and banks associated with Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile program and required Member States to notify the Security Council whenever an Iranian official designated for ties to Iran’s nuclear or missile program entered or transited its territory.

2008

March 8: U.N. Security Council Resolution 1803 called on states to “exercise vigilance” when providing export credits, guarantees and insurance to Iranian entities. The resolution specifically urged states to cut ties with Bank Melli and Bank Saderat, which the United States accused of providing financial services for Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs

2010

June 9: U.N. Security Council Resolution 1929 required U.N. member states to prevent the transfer of missile-related technology to Iran and prohibited Iran from developing or testing any nuclear-capable ballistic missiles. The resolution also enhanced previous travel restrictions and specifically targeted the Revolutionary Guards and the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL), a state-owned shipping conglomerate that was allegedly involved in transporting items related to Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile development.

2015

July 20: U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231 endorsed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) but called on Iran not to undertake any ballistic missile activity until October 2023 or until the International Atomic Energy Agency concluded that all nuclear activity in Iran was peaceful.

Photo credits: Zelzal upgrade process via BICOM (used with author's permission); Beirut missile site via Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs (public domain); Seized Missile by EJ Hersom via Department of Defense (public domain); Brian Hook by Lisa Ferdinando via Department of Defense (public domain); Fateh 110 by Hossein Velayati via Wikimedia Commons (CC by 4.0)

Julia Broomer, a research assistant at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, helped assemble this report