David Michel

Iran is, literally, being blown away. Stifling dust storms frequently now envelope both big cities and rural towns across much of Iran, the world’s 17th largest country. They threaten to disrupt crucial parts of public and economic life, education, commerce, public health, agriculture, trade and transportation. Swirling clouds – of windblown silt, soil, and sediment—already affected 23 of Iran’s 31 provinces in 2013, according to Vice President Masoumeh Ebtekar, head of the country’s Environmental Protection Organization.

Iran’s massive dust storms could also spill well across Iran’s borders, generating serious regional consequences and tensions. Dust clouds veiled Tehran for 117 days of the Iranian year which ran from March 2012-March 2013. And blinding sand storms blocked roads across the eastern province of Sistan and Baluchistan last summer, isolating nearly 60 towns and villages.

Iran’s massive dust storms could also spill well across Iran’s borders, generating serious regional consequences and tensions. Dust clouds veiled Tehran for 117 days of the Iranian year which ran from March 2012-March 2013. And blinding sand storms blocked roads across the eastern province of Sistan and Baluchistan last summer, isolating nearly 60 towns and villages. Dust storms regularly arise in arid and semi-arid regions around the world. Indeed, the Islamic Republic sits in the center of a Northern Hemisphere “dust belt” stretching from the west coast of North Africa, through the Middle East, and across South and Central Asia to China. Winds gusting over the open, level landscape of Iran’s dry plateaus, deserts, and salt flats readily pick up loose soil and sand, lifting bits of dirt and grit into the atmosphere and carrying it tens, hundreds, or even thousands of miles away.

Nationwide, erosion annually strips thousands of tons of surface soil and sediment from every square mile of the country. The resulting dust storms can close roadways, rail lines, and airports; choke crops; clog machinery; and cloak cities in debilitating air pollution, endangering public health.

Yet nature is not the only culprit stirring up the dust clouds that blot the country’s horizons. Iran’s own water and land management practices have worsened environmental conditions that exacerbate dust storms. So too, Iran’s neighbors have made equally detrimental policy choices, with damaging regional repercussions. And lurking behind these national and international pressures, global climate change may further increase drought and desertification across Iran and southwest Asia, potentially intensifying future dust and sand storms.

Darkness at Noon

With 90 percent of its territory classified as arid or semi-arid, Iran’s climate and topography render it naturally susceptible to dust storms. According to Iran’s National Action Programme to Combat Desertification and Mitigate the Effect of Drought, over 77,000 square miles of the country across 19 provinces are subject to significant wind erosion. The Islamic Republic typically suffers more than 500 dust storms annually, mainly in the spring and summer months as temperatures mount and rainfall wanes. In recent decades, the southwestern provinces have experienced anywhere from 60 to 130 distinct dust “events” every year.

With 90 percent of its territory classified as arid or semi-arid, Iran’s climate and topography render it naturally susceptible to dust storms. According to Iran’s National Action Programme to Combat Desertification and Mitigate the Effect of Drought, over 77,000 square miles of the country across 19 provinces are subject to significant wind erosion. The Islamic Republic typically suffers more than 500 dust storms annually, mainly in the spring and summer months as temperatures mount and rainfall wanes. In recent decades, the southwestern provinces have experienced anywhere from 60 to 130 distinct dust “events” every year. In eastern Sistan region, the town of Zabol can experience up to 80 dust storms in a year. The dry gusts, known to the locals as the “120 day wind” because they last throughout the summer, produce gales up to 75 miles per hour. Storms in the Sistan Basin can grow so intense they have been measured to contain more than 250 kilograms of dust per cubic meter of air. (For a roughly equivalent measure of density on a more familiar scale, imagine six pounds of dust whirling around the space inside a standard men’s shoebox.)

These thick dust storms can wreak serious damage. Billowing dust can reduce visibility to 100 yards or less, shutting down air and road traffic. Shops and schools close. Searing, sand-bearing winds blow down power lines. Grit-filled machines grind to a halt. Drifting dust buries crops and farmland, suffocates livestock, and fills wells and irrigation canals. One analysis of the area around Zabol estimated that the lost economic activity and physical damages from dust storms cost the city $100 million between 2000 and 2005.

Far more troublingly, Iran’s dust storms also impose serious public health risks. If inhaled, fine dust particles can penetrate deep into the lungs. They can cause infections, respiratory difficulties, and cardiovascular problems. The World Health Organization (WHO) has formulated specific guidelines about exposure to concentrations of airborne dust, soot, or other tiny pollutants, called “particulate matter,” that can threaten human health.

Studies of several Iranian cities have found particulate pollution routinely shooting far above these guidelines during dust storms. In the southwest city of Ahvaz, dust storms during the summer of 2010 increased daily pollution levels to between 13 and 16 times the WHO standards, causing an estimated 1,131 deaths and more than 8,100 hospital visits. An analysis of hospitals in Kermanshah province in western Iran calculated that every 10 percent rise in dust concentrations swelled the number of cardiac patients by 10 percent, respiratory patients by 5 percent, and deaths from heart disease by 3 percent.

Studies of several Iranian cities have found particulate pollution routinely shooting far above these guidelines during dust storms. In the southwest city of Ahvaz, dust storms during the summer of 2010 increased daily pollution levels to between 13 and 16 times the WHO standards, causing an estimated 1,131 deaths and more than 8,100 hospital visits. An analysis of hospitals in Kermanshah province in western Iran calculated that every 10 percent rise in dust concentrations swelled the number of cardiac patients by 10 percent, respiratory patients by 5 percent, and deaths from heart disease by 3 percent. Spreading Dust Bowls

Iran’s dust storms appear to be growing more frequent and severe. Compared to the past 30 years, the number of dust storms striking the Islamic Republic jumped markedly between 2000 and 2009, soaring by as much as 70 to 175 percent in the western provinces. Dust storms also increasingly occur in areas not as vulnerable as in the past. They have more than doubled in parts of the northeast – around Sabzevar – and in the northwestern provinces, especially East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, and Kurdistan.

These increases parallel regional climate changes. Over the past half century, much of Iran has become increasingly arid. Average temperatures have warmed up to nine degrees (five degrees Celsius) since 1960, while annual rainfall has dropped across much of the country, according to Iran’s Second National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Further global warming could exacerbate these trends. Iranian studies have projected that average temperatures could climb almost two degrees (about one degree Celsius) by 2039, while precipitation across the country could drop by 9 percent. A hotter, more arid climate would further dry the soil, creating more loose dust and sand to be swept away by the wind.

Reaping the Whirlwind

Climate pressures, though, are by no means the only factors driving Iran’s dust storms. Particular Iranian agricultural, land, and water management policies substantially aggravate the environmental stresses that worsen dust conditions. For example, over-grazing livestock are dramatically degrading much of the countryside, according to Iran’s Forestry, Rangelands, and Watershed Management Organization. Iran is now raising more than twice as many head of livestock as the land can sustainably support. Too many livestock grazing the same pastures have denuded the land of the grasses and other vegetation that hold the soil in place. Some 166,000 square miles of the nation’s rangelands are now in poor condition, and growing expanses of barren ground are in turn exposed to dust-generating winds.

Another problem is that Iran has cut down more than 20 percent of its forest cover since the 1950s to clear more land for farming and for burgeoning cities. Deforestation has removed trees that offer natural wind breaks to blunt the dust storms’ blasts.

Another problem is that Iran has cut down more than 20 percent of its forest cover since the 1950s to clear more land for farming and for burgeoning cities. Deforestation has removed trees that offer natural wind breaks to blunt the dust storms’ blasts. Government policies have contributed to Iran’s dust crises. Water management choices in the country’s northwest have transformed Lake Urmia, the great salt lake straddling the provinces of East and West Azerbaijan, into a nascent dust emissions hotspot. Dams and diversions on the rivers feeding Lake Urmia –to provide water for irrigation, industry, and other uses – have significantly diminished the flows entering the lake downstream. Reduced river flows, combined with recurrent drought in the region, have drastically lowered the lake’s water levels.

In the past two decades, Lake Urmia, once the largest in the Middle East, has lost 60 percent of its surface area, shrinking from around 2,300 square miles in the 1990s to about 890 square miles today. As a result, winds that used to ripple the lake’s shallow saltwaters now blow over dry land, carrying off clouds of salt-loaded silt from the desiccated lakebed. These so-called “white” or “saline” dust storms are particularly damaging to surrounding agricultural areas because the windblown salt coats crops, harming their growth, and contaminates soils, decreasing their productivity.

Similar strains weigh on the marshes and salt lakes – called Hamouns – of the Sistan Basin on the eastern border with Afghanistan. Water levels in the shallow Hamoun system, nourished by the Helmand and other smaller rivers coming in from Afghanistan, fluctuate naturally, depending on regional precipitation and snowmelt in the basin. But here too, water withdrawals for irrigation and the development of Iran’s Chah Nimeh reservoir, together with prolonged drought, have cut water flows into the Hamouns. Water levels in the lakes have plunged, uncovering growing patches of dry lakebed. As a result, satellite observations and data on the ground show that dust storms in the area are increasing as the Hamouns dry up.

Dust Diplomacy

Lake Urmia and the Sistan Basin highlight the regional nature and international implications of Iran’s dust challenge. Though particular storms may originate in Iran, the repercussions reach the neighbors as well. The prevailing winds sweeping over Lake Urmia, for instance, can loft dust thousands of feet into the air and carry it northward 150 miles or more into Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Likewise, the Sistan Basin represents a major dust source for all of southwest Asia, and storms starting in the Hamouns can spread salt-laden sediment across Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

Lake Urmia and the Sistan Basin highlight the regional nature and international implications of Iran’s dust challenge. Though particular storms may originate in Iran, the repercussions reach the neighbors as well. The prevailing winds sweeping over Lake Urmia, for instance, can loft dust thousands of feet into the air and carry it northward 150 miles or more into Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Likewise, the Sistan Basin represents a major dust source for all of southwest Asia, and storms starting in the Hamouns can spread salt-laden sediment across Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Iran is also vulnerable to dust storms born beyond its borders. By tracking satellite images and analyzing the mineral composition of windblown dust particles, scientists can determine where dust storms begin. Their studies indicate that Iraq, Syria, and Saudi Arabia are significant sources of dust storms affecting Iran. Even as far from the frontier as Tehran, 90 percent of the dust shrouding the capital during the dust storms of 2009-2010 originated in the deserts of Iraq and Syria, according to a study by experts at Iran’s Sharif University of Technology.

Dust storms bind Iran together with its neighbors in a reciprocal relationship. Iran’s land and water policies fuel dust storms that blow across borders, especially Iraq and Afghanistan. Iran has dammed and diverted waters from numerous streams and tributaries that run from its territory into the Tigris-Euphrates, including the Alwand, Karun, and Sirwan rivers that flow into Iraq. And falling water levels in the Hamouns – and their effects on Sistan dust storms – depend on water flows from the Helmand River, which Iran and Afghanistan share.

So too, land and water use decisions by the neighboring countries generate dust storms that can blow into Iran. Many Iranian experts worry that growing water demands and new dams and diversions by Iraq, Syria, and especially Turkey may dry out portions of the Tigris-Euphrates Basin, increasing desertification and promoting dust storms that could push deep into Iran.

So too, land and water use decisions by the neighboring countries generate dust storms that can blow into Iran. Many Iranian experts worry that growing water demands and new dams and diversions by Iraq, Syria, and especially Turkey may dry out portions of the Tigris-Euphrates Basin, increasing desertification and promoting dust storms that could push deep into Iran. Iran and its neighbors recognize their interdependence and have agreed to cooperate in recent years. In 2009, Iraq and Iran inked an accord under which Iraq was to dampen the dust threat by pouring either a biological or an oil-based mulch onto dust sources in the desert. In 2011, they signed a deal to jointly fund a $1.2 billion project to cover 3,860 square miles of Iraqi desert with mulch to stabilize the sand. Yet little has come of these agreements and the Iraq-Iran deal has never been fulfilled. In 2010, Iraq, Iran, Syria, Qatar, and Turkey concluded an agreement in Tehran to exchange information, technology, and experience for reducing dust storms. But that, too, is only a beginning.

Iran’s leadership is clearly thinking about environmental issues. On March 5th, 2014, National Tree Planting Day, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, urged all parts of the government, and all Iranians, to cooperate to protect the environment and resolve the dust storm challenge. And on March 29, Foreign Minister Javad Zarif tweeted a reminder for people to turn off their lights for “Earth Hour” 2014.

I switched off my lights for an hour earlier tonight -- did you? #EarthHour

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) March 29, 2014David Michel is director of the Environmental Security Program at the Stimson Center, a non-partisan think tank in Washington D.C.

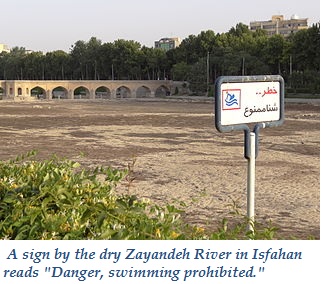

Photo credit: Tehran Pollution by Matthias Blume [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, Zayandeh River by Adam Jones [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, Lake Urmia by NASA via Flickr, Khamenei.ir