Hanif Kashani and Garrett Nada

Iran’s new government has taken only token steps to restore basic freedoms or open up politically during Hassan Rouhani’s first 100 days in office. The cleric had campaigned on an ambitious platform that included free speech, release of political prisoners, and gender equality. He generally pledged to “break this security atmosphere.”

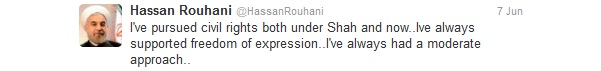

“A successful domestic policy means peace of mind, security, prosperity,” he said in the June 7 presidential debate. “Freedoms should be protected.”

After his inauguration, the government announced release of some 80 political prisoners in September, but by November only half had actually been freed. The United Nations reported in October that “hundreds of other prisoners detained solely for exercising their freedom of expression, association and assembly” remain jailed. Up to 800 political prisoners and prisoners of consciousness may be behind bars in Iran, according to an investigation by The Guardian.

The most telling case involves the detention of Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, two presidential candidates in 2009 who led protests against the disputed reelection of former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Hardliners charged them with sedition, although they have never been tried.

The slow pace of change has begun to alienate some of Rouhani’s supporters. After visiting Karroubi’s family on October 29, reformist leader and former interior minister Abdollah Nuri warned Rouhani, “Do not forget the substantial amount of supporters who voted for you because they are fed up with lawlessness, the violation of civil rights, harassment, and the narrow-mindedness of them [government officials].”

The slow pace of change has begun to alienate some of Rouhani’s supporters. After visiting Karroubi’s family on October 29, reformist leader and former interior minister Abdollah Nuri warned Rouhani, “Do not forget the substantial amount of supporters who voted for you because they are fed up with lawlessness, the violation of civil rights, harassment, and the narrow-mindedness of them [government officials].” The failure to deliver has also sparked growing criticism from the human rights community. “President Rouhani has an immense responsibility to uphold his promises to protect citizenship rights and use all means at his disposal to stop this latest onslaught against civil and human rights,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. “His silence in the face of such an affront is emboldening hardliners in the Judiciary and Intelligence who insist that Rouhani’s election will not change the status quo.”

Human Rights

During the presidential campaign, Rouhani repeatedly pledged to work for the release of political prisoners. At a June 1 rally, his supporters chanted “Political prisoners must be released!” Rouhani replied, “Why just political prisoners? Let’s do something in which all prisoners [of conscience] will be released!”

The judiciary, intelligence agencies and national security apparatus all play roles in arrests and trials, but the presidency has influence both through its popular mandate and a seat on the Supreme National Security Council. Since Rouhani’s inauguration, a handful of notable prisoners of conscience have been released, including human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh and journalist Isa Saharkhiz. Student activist Majid Tavakoli, jailed since the 2009 protests, received a temporary furlough from prison in October.

Yet the Rouhani administration has not prevented new arrests or executions. Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi dismissed government promises as “a big lie. Twelve or thirteen people have been released but these are people who had served their time,” she told the Associated Press in November.

Recent high-profile arrests include actress and activist Pegah Ahangarani (below), who was sentenced to 18 months in October on security charges. She campaigned for Rouhani as well as 2009 presidential candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi. Human rights groups also reported that at least 125 executions had been carried out between Rouhani’s election in June and his first three months in office.

Presidential Candidates

The continued detention of former presidential candidates Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi is the most visible example of Rouhani’s failure on human rights. Both men worked closely with Rouhani in the 1980s, during the revolution’s first decade, when Mousavi was prime minister and Karroubi speaker of parliament. The opposition leaders (below) have been under house arrest since February 2011 for leading the Green Movement protests that challenged former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s 2009 reelection.

During the presidential campaign, Rouhani promised action. “I don’t think it will be difficult to bring about a condition in the next year where not only those under house arrest but also those who have been detained after the 2009 election will be released,” Rouhani said in May.

Hopes for the Mousavi and Karroubi’s release were dampened in late October. Mousavi’s daughters were attacked by female guards after visiting their father and mother. Nargess Mousavi wrote about the encounter on her Facebook page:

“We couldn't believe it at first, but she [the guard] unabashedly repeated her demand [to search the daughters], even saying she wanted us to take off our underwear. To try and describe her treatment of us defies basic human decency. After refusing to take off our underclothes, she attacked us and smacked both my sister Zahra and myself in the ear with a great deal of force.”

Rouhani’s silence on the incident prompted harsh criticism from some prominent supporters. “Our first condition was for you to try to release all political prisoners, particularly to end the house arrest of Mousavi and Karroubi,”Ayatollah Ali Mohammad Dastgheib was quoted as saying on opposition websites. Dastgheib is a member of the Assembly of Experts, the powerful body charged with overseeing Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Gender Equality

Rouhani’s campaign platform promised women “equal rights and equal pay,” including equal opportunities for men and women in senior government positions. He also pledged financial support for female heads of households and promised to create a ministry of women’s affairs. In contrast, conservative candidate Saeed Jalili argued that the “main role for a woman is to be a mother.”

During his first 100 days, Rouhani did appoint women to some prominent positions, including two vice presidencies. Elham Aminzadeh is vice president for legal affairs. Masoumeh Ebtekar is vice president and head of the Environmental Protection Organization. At the foreign ministry, Marzieh Afkham is Iran’s first female spokesperson. He vowed to appoint many more. “You’ll see women active everywhere,” Rouhani said during his New York visit in September (video below).

Although he is a cleric, Rouhani also criticized police enforcement of Iran’s strict Islamic dress code, which requires women to cover their head and shoulders. “If there is a need for a warning on the hijab issue, the police should be the last to give it,” he told police academy graduates in October. “Our virtuous women should feel safe and relaxed in the presence of the police,” he added.

But Rouhani is now trapped between hardliners who are pushing back on gender equality and women who want him to move further and faster. The Association of Iranian Women demanded that Rouhani address women’s issues and treatment of “feminism as a taboo subject” within the first 100 days of his presidency. “There is no excuse for the president to claim he is powerless to advance women’s rights in Iran,” prominent human rights lawyer Mehrangiz Kar told the Brookings Institution in October.

Academic Freedom

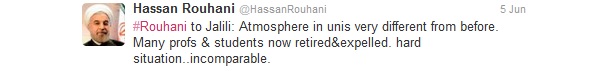

During the campaign,Rouhani promised greater freedom of expression, especially on university campuses. In the June 5 presidential debate, he condemned the forced retirement of professors and expulsion of student activists since nationwide protests in 2009. His Twitter account even chastised hardline candidate Saeed Jalili, a close associate of former President Ahmadinejad.

Since taking office in August, Rouhani has continued to press for more freedom in universities. “It would be a shame if professors could not express their opinions,” Rouhani saidat Tehran University on October 14. “University officials should respect freedom of expression, and we should not be involved in the bad and inappropriate tendency of sending teachers into early retirement. I call on the security services to pave the way to that diplomacy and to trust professors and students."

In September, Rouhani dismissed Sadreddin Shariati, the president of Allameh Tabatabai University, for his role in the dismissal of faculty and politically active students. Shariati had also tried to segregate coed classrooms.

But little has actually changed. The government also has not reversed policies that prohibit women from enrolling in 77 fields of study —including engineering, accounting, education, counseling, and chemistry— or that replace women’s studies curricula with courses on women’s rights in Islam at universities, according to a U.N. report in October. The government has also not canceled quotas that favor admission of men to universities. Few of the roughly 1,000 students who were expelled after the 2009 protests have been allowed to return to school, according to Nobel Peace Prize winner Shirin Ebadi.

Hanif Z. Kashani is a consultant for the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Middle East Program.

Garrett Nada is the assistant editor of The Iran Primer at USIP.

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org